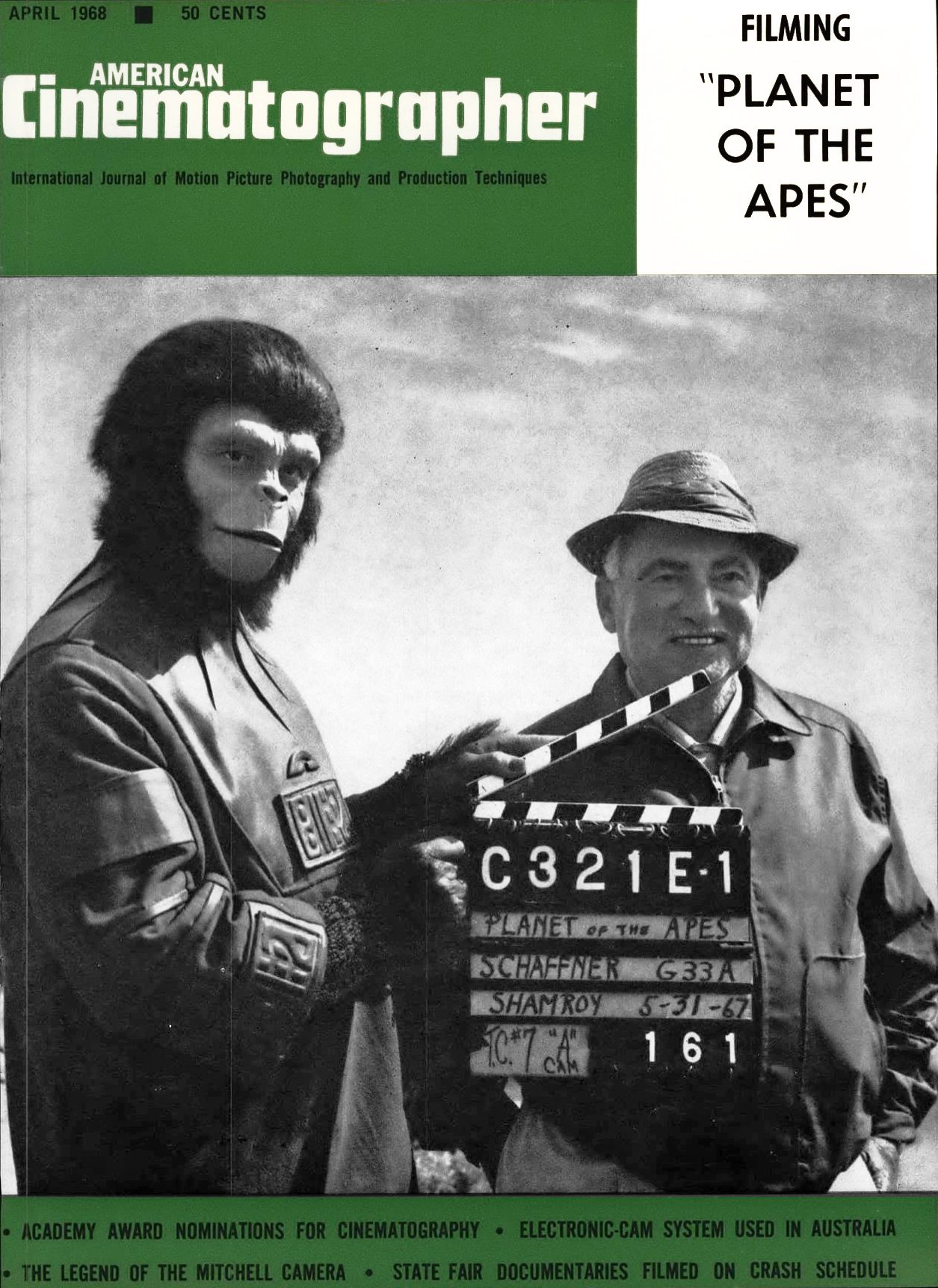

Filming Planet Of The Apes

Cinematic artistry in every department makes science-fiction thriller an allegory for our times.

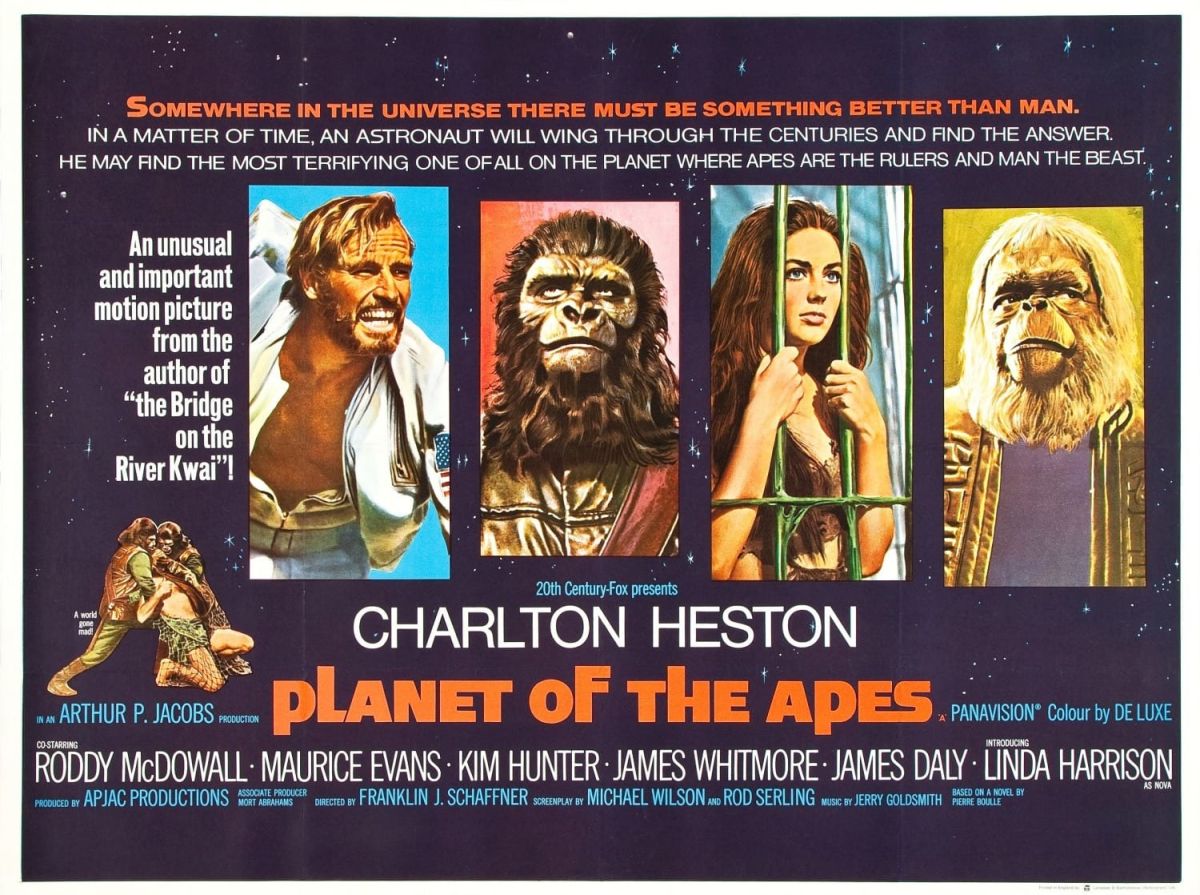

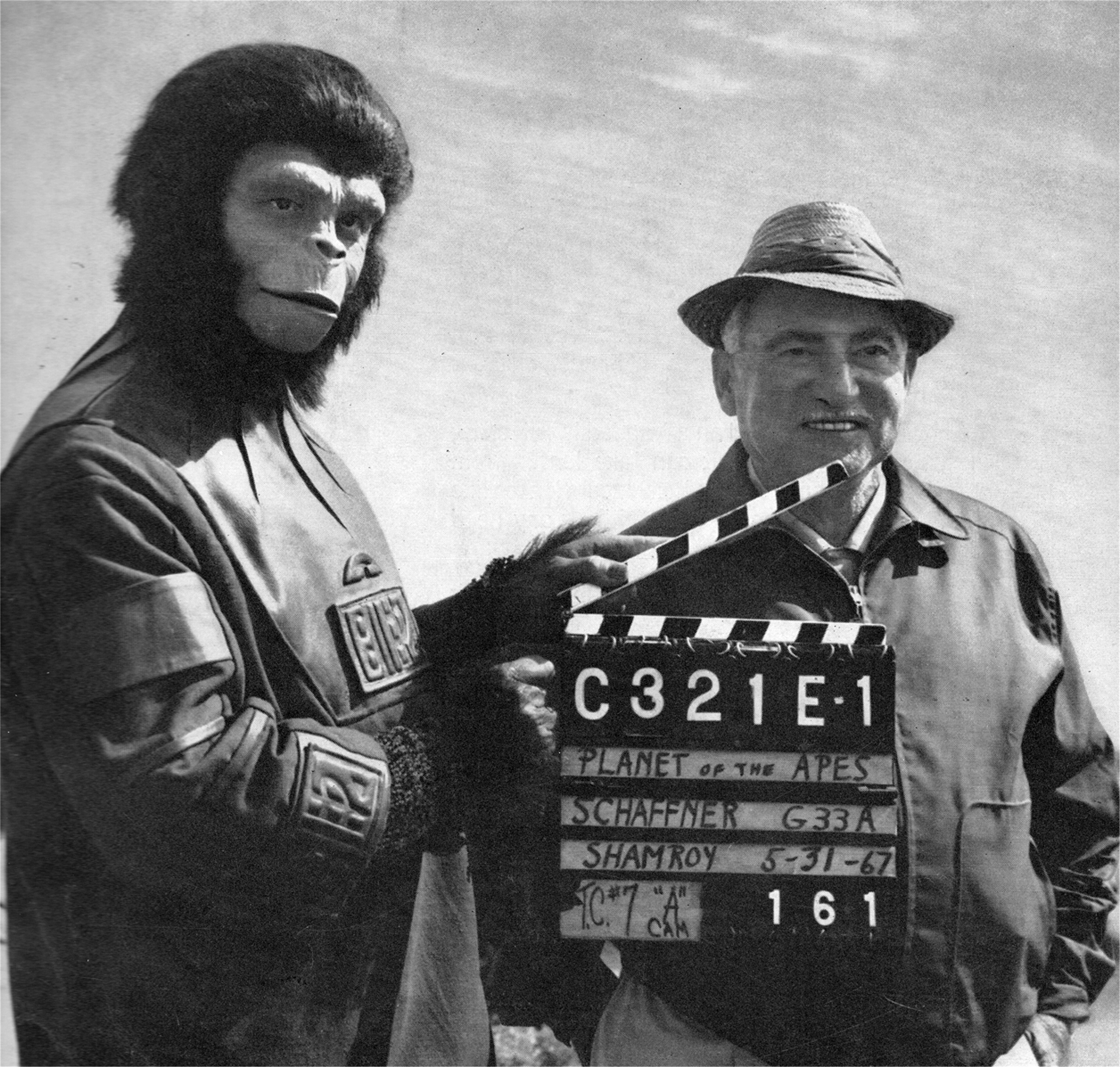

In less competent hands, the APJAC-20th Century-Fox production of Pierre Boulle’s Planet of the Apes might have been just another science-fiction film fantasy which, in this case, makes monkeys out of actors. However, as produced by Arthur P. Jacobs, directed by Franklin J. Schaffner and photographed by Leon Shamroy, ASC, it flows onto the wide screen as a tremendously exciting, technically superb adventure film that successfully combines spectacular action with an unobtrusively stated “message” of rather profound social significance.

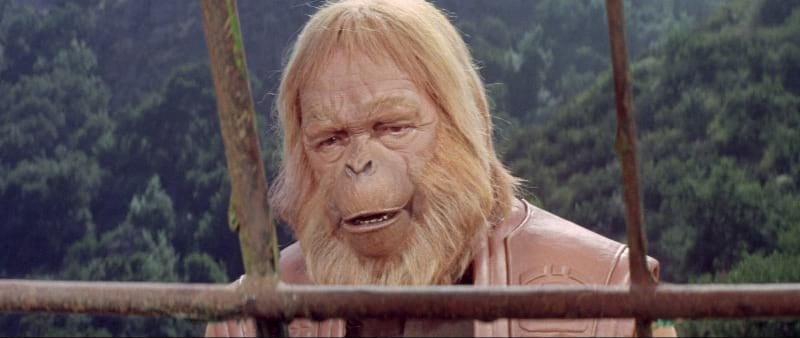

It is an off-beat yarn (to say the least) and one which, even to the novel’s author, seemed to defy credible translation into cinematic terms. In the first place, it calls for all of its leading characters but one to appear as apes — orangutans, chimpanzees or gorillas—throughout the entire unfolding of its story. Moreover, the ape makeup had to be entirely believable: despite their elaborate disguise the actors’ faces had to be able to convey even the subtlest emotional reaction. The audience had to be led to accept the ape characters as intelligent beings, capable of thought, speech, even scientific and artistic achievement. The resultant film was to be no masquerade party. It had to seem very much for real.

Secondly, Boulle did not write La Planete des Singes with the screen in mind. Although well able to stand on its own as an adventure film with much action, intrigue and suspense, the story is an allegory for our times with some of the flavor of Jonathan Swift and a dash of Jules Verne. It was Boulle’s hope that readers could recognize the human species reflected in the behavior of the apes’ society, and he dissects with subtle irony the stupidity of certain elements of established authority, as well as the vanity of human ambition.

It was almost a foregone conclusion that the ideal author to transcribe this story to the motion picture medium would be Rod Serling, the writer whose Twilight Zone TV series was his hallmark as an expert in science-fiction drama.

So Serling was retained by an independent producer to do just that. But the project entitled Planet of the Apes raised such challenges of concept and makeup that it was dropped and lay dormant for many months. Eventually, another filmmaker, Arthur P. Jacobs, exercised an option on the property, and made it into the current screen version.

“One reason it was so long in reaching fruition was the fact that the apes are intelligent and civilized. They wear clothes and speak English,” says Serling in retrospect. “Now, as soon as you put a shirt and tie on an orangutan you invite laughter — but our story is a serious satire.

“We had to find a way to handle this properly. I decided to let the human characters in the story laugh right along with the audience when they first discovered these dressed-up apes. But the humor turns to horror when the apes pick up guns and begin shooting at the humans," relates Serling.

While Serling’s original script was later refined and somewhat changed by writer Michael Wilson, Serling’s interest and enthusiasm for the offbeat project never flagged. “There is no parallel with any other film," he says. “We have a shocking ending which could stay with the viewers for a long time after they’ve seen the picture.

The film version of Planet of the Apes begins at a time not too far in the future when interplanetary travel has become a technically feasible reality.

Hurtled some 2,000 years through time and space, measured in terms of interstellar mathematics, four American astronauts crash land in the wilderness of an unidentified planet when their spacecraft suffers a navigational malfunction.

The lone female in the quartet dies, but the male survivors trek across countless miles of arid desert until they discover life-supporting vegetation and stumble upon a sub-human populace living like animals in the woods.

Their freedom is short-lived, however, for they are captured by a band of mounted hunters — uniformed gorillas on horseback. The astronauts are separated from each other. One is mortally wounded and ends up as a mounted specimen in the simian’s museum of natural history. Another is taken to a laboratory where ape scientists remove his frontal lobes in medical experimentation.

The group’s erstwhile leader, Taylor (Charlton Heston - Ben-Hur), is wounded severely in the throat and taken to an animal hospital where he is incarcerated after primitive medical attention. As he recovers consciousness he is amazed to find that he is a prisoner in a society dominated by intelligent simians, an autocratic social order in which humans are feared as beasts of prey — and treated as such.

From that point on, and continuing up until its completely unexpected shock ending, the film becomes furiously paced exercise in suspenseful action, spiced with ironic humor.

In perhaps no film ever made has makeup been so totally essential to the believability of the story — nor presented such unique challenges. The massive makeup problems invoked the collaboration of chemists as well as makeup design artists, sculptors and wig-makers. Initial substances employed to change human features into the likeness of simians stiffened on the actors’ faces so that their features were neither mobile nor expressive. Furthermore, the actors could not chew, and there was the prospect that they might have to subsist for weeks on a liquid diet. Experimentation with new rubber compounds, tempered with other chemicals and substances, resulted in the development of materials which permitted full facial mobility to the actors and allowed their skin to breathe inside the heavy outer layer of ape makeup.

But in Hollywood, as probably nowhere else, time is of the essence, and at first this makeup required six to seven hours to apply and three hours to remove. Obviously, no actor can be asked to show up for work at two in the morning and work through until ten at night — nobody could survive such a schedule five days a week for several months. Hence, new techniques had to be invented to speed up application and removal of the disguises. Ultimately, a small army of specialists was trained to apply the makeup in three to four hours and remove it in one to two hours.

If Academy Oscars were awarded in a Makeup category, surely a top contender would be John Chambers, who is credited with “Creative Makeup Design” on the film.

“We had to develop a believable chimpanzee, gorilla and orangutan makeup that could be worn as long as 14 hours at a time by such stars as Kim Hunter, Roddy McDowall, Maurice Evans and James Whitmore,” he says.

“So we experimented with a foam rubber so molecularly constructed that, even when worn like a mask, it allows the human skin to breathe naturally under it. Then we came up with a paint — a makeup paint — with which the rubber can be covered without closing the invisible pores.

“And we also produced a new variation of adhesive which allows us to fasten these foam rubber appliances — be they full masks or just cheeks, chins, brows, lips or even ears — to the human skin without irritating it or clogging the pores.”

By “we” Chambers means the team of experts with whom he worked, headed by 20th Century-Fox makeup chief Dan Striepke.

These advances pioneered by the makeup crew on Planet of the Apes have far-reaching commercial and even therapeutic potential. Should someone have a nose he doesn’t like, or a chin which recedes too much, it is now possible to have a new one designed to his liking which would then be fabricated of foam rubber, painted to match his complexion, and glued to his face with the new adhesive.

“We’ve already used these techniques on some of the war-wounded,” says Chambers’ fellow makeup ace, Don Cash. “Now, if a man sustains a horribly scarred cheek in an accident, or if his nose or lip is eaten away by cancer, we can in some instances give him a corrective appliance which returns his appearance to normal.”

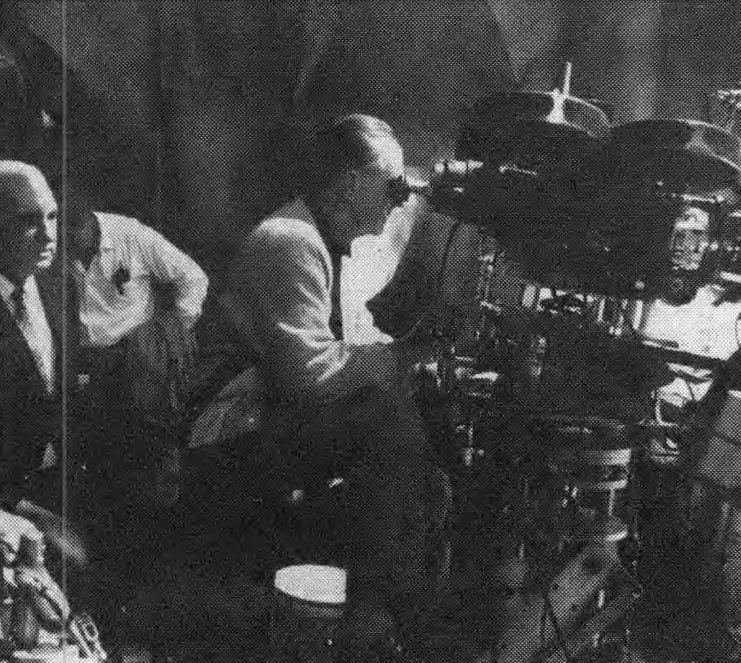

For director of photography Leon Shamroy, ASC, the unique photographic demands of Planet of the Apes represented a stimulating challenge — plus an opportunity to explode the myth that he is essentially an “interior” cameraman.

Before actual filming began, he went off on several scouting expeditions with the director in order to find precisely the right locations for the unusual script.

“We were looking for a landscape weird and ‘unearthly’ enough to suggest the possible terrain of another planet,” he observes. “The surface topography had to include formations that appeared tortured, chaotic — yet with a certain heroic, majestic scope. At the same time we hoped to find a place where the earth was a ghostly gray-green color, rather than the characteristic red of Arizona.”

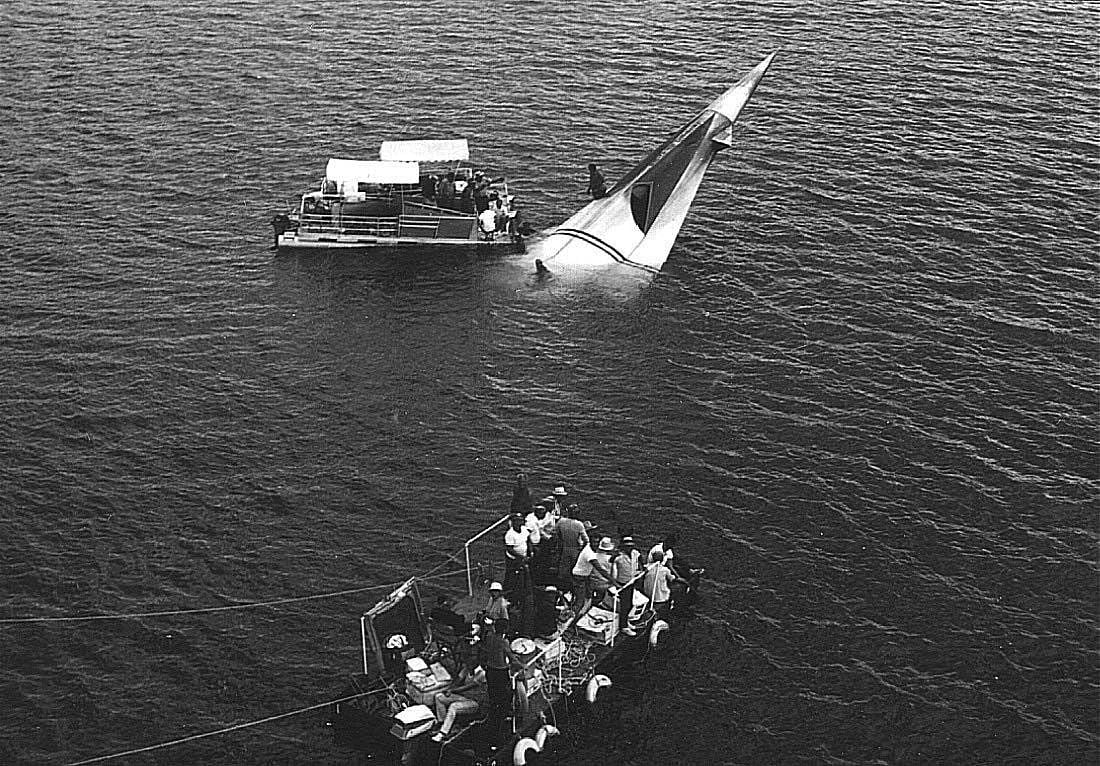

After considerable exploration of possible sites, a spectacular location having the required geographical elements was located. Exterior sequences appearing early in the film and depicting the astronauts’ trek across the unidentified planet were filmed in the magnificent wilderness around Lake Powell on the Colorado River in Utah and Arizona. Camera crews penetrated areas seldom if ever trod by man, deep in the badlands interior, carrying camera and sound equipment by foot or mule pack team. Opening shots of the film graphically depict the space vehicle’s splashdown upon the unfriendly planet, and the surviving astronauts’ escape from the sinking craft which had been their home in space for 18 calendar months — but some 2,000 years in terms of the mathematics of time and space. This footage was photographed at a point on the Colorado River known as Crossing of the Fathers.

On the screen the area appears to be a lake surrounded by eerie rock formations so exotic in structure they can scarcely be believed. Nearby Glen Canyon has terrain which, according to NASA, is akin to that on the moon. For the first time, the government permitted a film company to shoot within the top security area at the foot of Glen Canyon Dam, through which the waters of the Colorado River boil to power tremendous generators which provide most of the electrical power to the Southwest.

Moving cast, crew and equipment into this desolate area was a major undertaking. “We could build only one road part-way into the area — and from that point on we had to hoof it for several miles,” Shamroy recalls. “People were passing out from heat and exhaustion all over the place. It was the roughest filming experience I’ve ever had — but it was worth it to be able to photograph the action in that wonderful terrain. God is a helluva set designer!”

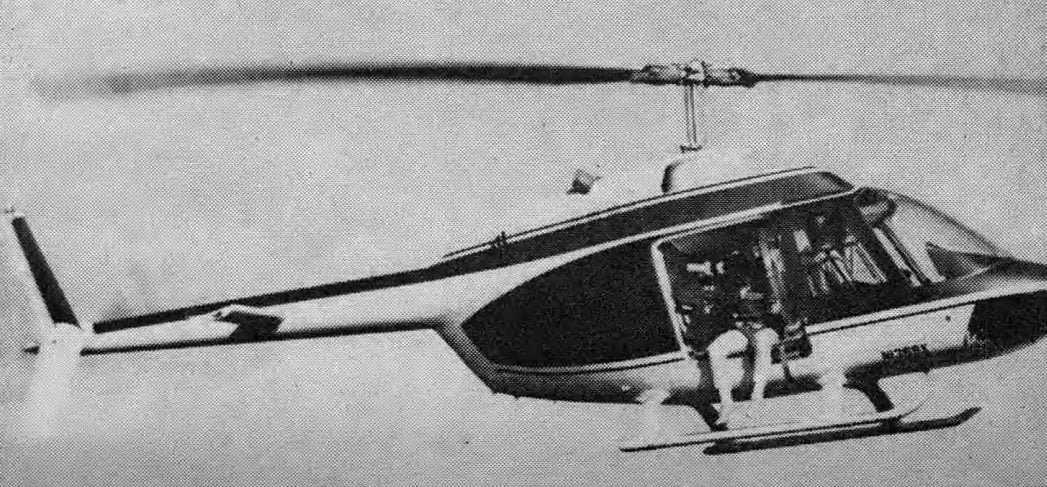

A small brigade of helicopters was flown in to aid in the aerial filming to be done with equipment and crews provided by Tyler Camera Systems. Because of the temperature and altitude demands of this high desert location, it was found that a jet helicopter was the only type that would perform satisfactorily. TCS was called upon to quickly construct, at a cost of $13,000, a special version of the Tyler Vibrationless Camera Mount which could be installed in a Bell Jet Ranger helicopter.

Additional equipment included cameras, lights, a giant camera crane and a miniature armada of boats (including special camera craft) which had to be trucked in from California.

Shamroy’s precisely executed off-beat photography definitely sets the other-worldly pictorial style of Planet of the Apes in the prologue before credits, during which the astronauts are established in the low-key lighted interior of the spaceship as it glides through a space field of multi-colored glowing gas-clouds artfully conceived (via the bluescreen-matte process) by L. B. “Bill” Abbott, ASC and his staff of 20th Century-Fox Special Effects wizards.

Blue screen magic is again brought into play as the spaceship spins out of control and plunges underwater into a lake on the unidentified planet. As the capsule bobs to the surface and the characters emerge from it, the camera is skilfully used to accentuate the mood of a weird and threatening environment. The astronauts are photographed trudging along in back-lit silhouette against an eerie sky, with the sun blazing squarely into the lens. The ghostly, shimmering patterns produced by refraction and reflection of the direct sun rays between the elements of the lens create a bizarre effect that adds mightily to the visual mood.

Because he wished to get a subjective quality into the photography (and also because there were times when nothing else would work) Shamroy relied heavily upon the use of hand-held Arriflex cameras in these opening sequences. He has lavish praise for the camera operators who worked so closely with him on Planet of the Apes. “The operator is a very important guy,” he comments, “and I was lucky to have three of them who were tops — Al Lebowitz, Irving Rosenberg and the late Paul Lockwood. They did some wonderful work on this picture, especially with the hand-held cameras. There was one sequence where the astronauts go skidding down a steep bluff. In order to get a subjective shot that would tie in, we improvised a ‘sand-sled’ made from a piece of corrugated steel and two boards. Lockwood got on it with an Arriflex and we shoved him down the slope.”

Brute arcs and Molefay multiple quartz-iodine lamp clusters (faced with dichroic filters) had been brought along to provide fill for the harsh desert sunlight, but there were several locations so cramped and remote that it was impossible to set the lamps where they should be. In such cases Shamroy resorted exclusively to reflectors, and when the quarters became too tight even for those, he shot with no fill light at all, achieving an appropriately stark quality by letting faces go almost into silhouette against the sky.

After sequences filmed in the Colorado River area were completed the cast and crew returned to California where not-so-distant location filming continued. The “Ape City” and its environs were constructed on the 20th Century-Fox ranch in the San Fernando Valley.

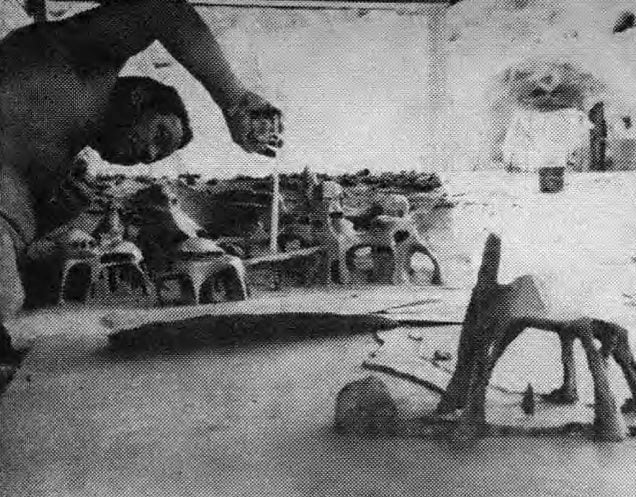

The city itself is of a very distinctive design, blending set elements which are a combination of classic, modern and primitive motifs. Perhaps the most amazing facet of this simian metropolis, however, is the material of which it is fabricated.

The whole city was fired from a gun. “We built the entire set in very quick time out of polyeutherthane foam,” explains Ivan Martin, head of the studio’s construction department. “The material is NKC CoroFoam, a combination of resin and a catalyst. When these are fired under pressure from a gun, the mix rises like bread dough. Then the heat quickly dissipates, and within 10 minutes it is cold — and solid.

”Martin’s highly skilled crews first built basic outlines of the many edifices in the ape city out of pencil-thin iron rods. These thin skeletons were then draped with heavy craft paper which could be formed into whatever shape might be desired. The foam was hosed onto the paper and, after it had hardened, the paper was simply peeled off, leaving a solid structure which looks like shaped stone. Coro-Foam is 20 times lighter than plaster

The monolithic buildings, with their odd causeways, arches and forums, presented provocative compositional elements for Shamroy’s camera. They also served as multi-leveled platforms for furious chase and fight action photographed by multiple hand-held Arriflexes.

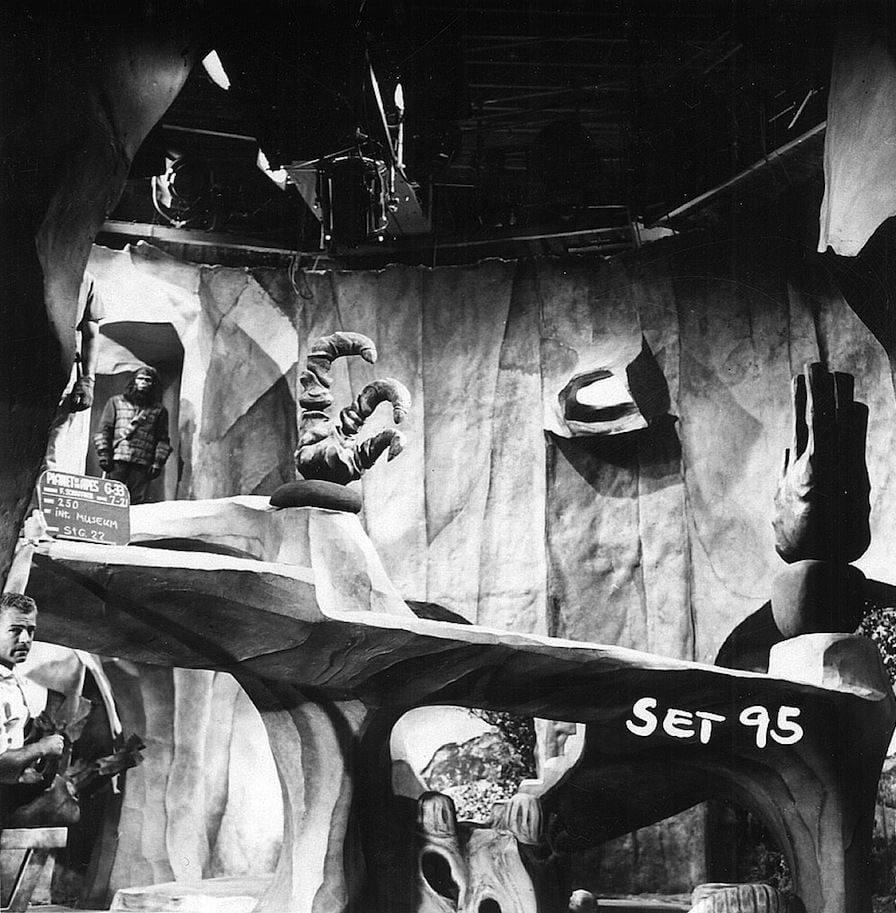

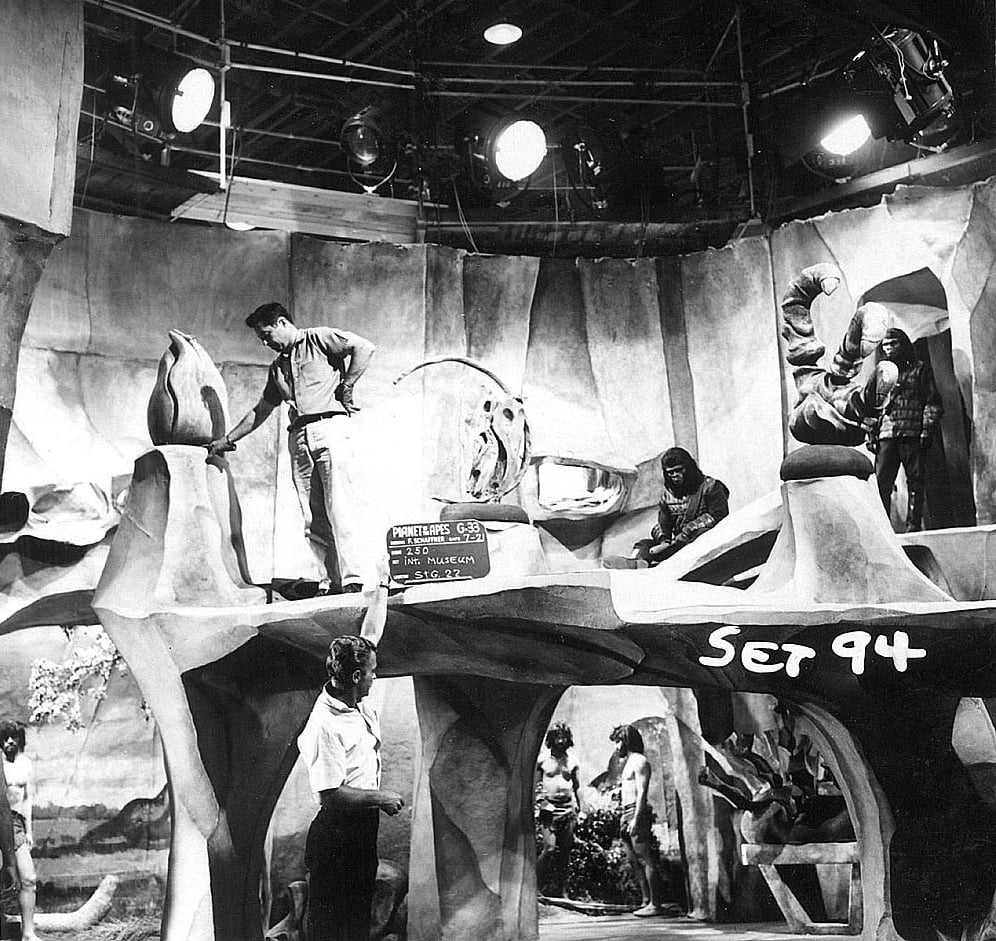

be filmed on 20th Century-Fox sound stage.

Similar action and hand-held camerawork prevailed in sequences where the horseback-mounted apes hunt down and kill or capture the primitive humans who graze in herds over the nearby countryside. To make this action more spectacular it was decided that the melee should take place in dense vegetation taller than a man’s head. A section of the 20th-Fox ranch was planted with a fastgrowing species of corn and, by dint of a crash irrigation program, within six weeks the artificial veldt was covered with lush vegetation seven feet high.

Also filmed at the ranch was a pictorially beautiful sequence in which the astronauts go swimming in a pool beside a magnificent waterfall that looks like an inspired creation of nature but is, in reality, an admirable example of man-made geography, complete with artificial plumbing.

The final sequence of the picture was filmed along a savagely beautiful stretch of California seacoast between Malibu and Oxnard. Towering cliffs 130 feet high made the beach inaccessible by road or trail, which meant that cast, crew, equipment and horses had to be lowered onto the sand in a huge “bucket” suspended from a giant crane.

While it might seem that photographing apes would be fun — something on the order of a Walt Disney romp — getting the simulated simians onto film with the best possible result actually presented a few problems. In the first place, the dark furry makeup offered nothing that could be effectively highlighted except, of course, the eyes. Also, since the actors wore false protruding jaws fitted with apelike incisors, a certain amount of care had to be taken in lighting and the selection of camera angles to make sure that two sets of teeth would not be visible — in the same mouth, that is.

Perhaps the most difficult set to light and photograph in the entire film was the interior of the apes’ museum, where humans in a fine state of taxidermy were presented in tableaus simulating their natural habitats. The set, a triumph of art direction, featured many alcoves on split levels, with flying buttresses of convoluted design snaking about. Further complicating matters was the necessity for shooting several scenes in which the camera, without a cut, followed action in a 360-degree pattern. All lights had to be mounted overhead, and keeping them hidden behind pillars and beams was a continual problem. Add to this the fact that the peculiarly proportioned sets had no “shape” (in the conventional sense), which precluded the use of forced perspective:

Shamroy, an acknowledged master of the artistic employment of colored light, used little of it in Planet of the Apes.

“I feel that colored light should be used sparingly,” he explains, “—not purely for decorative effect, but to simulate realistically a light source that would naturally have a special color cast to it. I believe in trying for a certain realism, even when shooting a fantasy. Of course, no two cameramen shoot a scene in exactly the same way. Cinematography is highly individual because it is basically an emotional art. The only hard fact about it is getting the proper exposure.”

Throughout the entire film Shamroy has utilized a simple, clean and direct style — with no obvious tricks to mar the realism of what is essentially an unreal subject. He used no special filters. He did use a 10-to-1 zoom lens in a few selected scenes, but he even has certain reservations about that often-convenient instrument.

“The zoom lens can come in handy now and then, but I'm getting a bit tired of zoom lenses because I feel they’re over-used,” he comments. “Some directors consider the zoom lens to be just another toy, and they use it that way. It can sometimes speed things up if you use it as a variable focal-length lens, instead of for actual zooming — but, generally speaking, zoom lenses have a shallower depth-of-field and are not as sharp as fixed focal-length lenses. A zoom lens, smoothly operated, can simulate camera movement to a certain extent, but it will not take the place of a dolly, because the effects on perspective are quite different.”

In photographing Planet of the Apes, Shamroy used the 35mm Panavision lens quite often in order to accentuate the drama, and resorted to telephoto lenses where he wished to get a subjective feeling of the natives of the planet peering at the astronauts from concealed vantage points.

When filming on the Arizona-Utah high location, he discovered that certain alterations in his usual method of exposure control had to be made. Due, probably, to the extreme clarity of the air in the high desert, he found it necessary to stop down one full f/stop below what the incident light meter indicated, in order to keep from overexposing the scene.

Though it was a physically exhausting assignment, Shamroy regards Planet of the Apes as a pleasant and productive one. “The cameraman is expected to be a thorough professional, at the very least — and most of them shooting pictures today are,” he points out, “but unless there is a good ‘marriage’ between the director and the cameraman it’s hard to get anything really inspired onto film. In this case, the director, Franklin Schaffner, and I formed a true entente. We enjoyed an especially close rapport because he is very pictorially minded and has a fine feel for the camera. He would visualize a sequence in his mind’s eye and then tell me what he wanted. From that point on it was up to me to get the result photographically.

“Schaffner deserves a great deal of credit for his work on this film. He was indefatigable on the set and his energy was so contagious that everyone in the cast and crew became dedicated — determined to make it a good picture. We had to work hard to get the result — and we had our share of adversity — but nothing good ever comes easily.”

For fans of the more recent Ape movies, cinematographer Michael Seresin, BSC discusses shooting Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) in this AC Podcast episode.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.