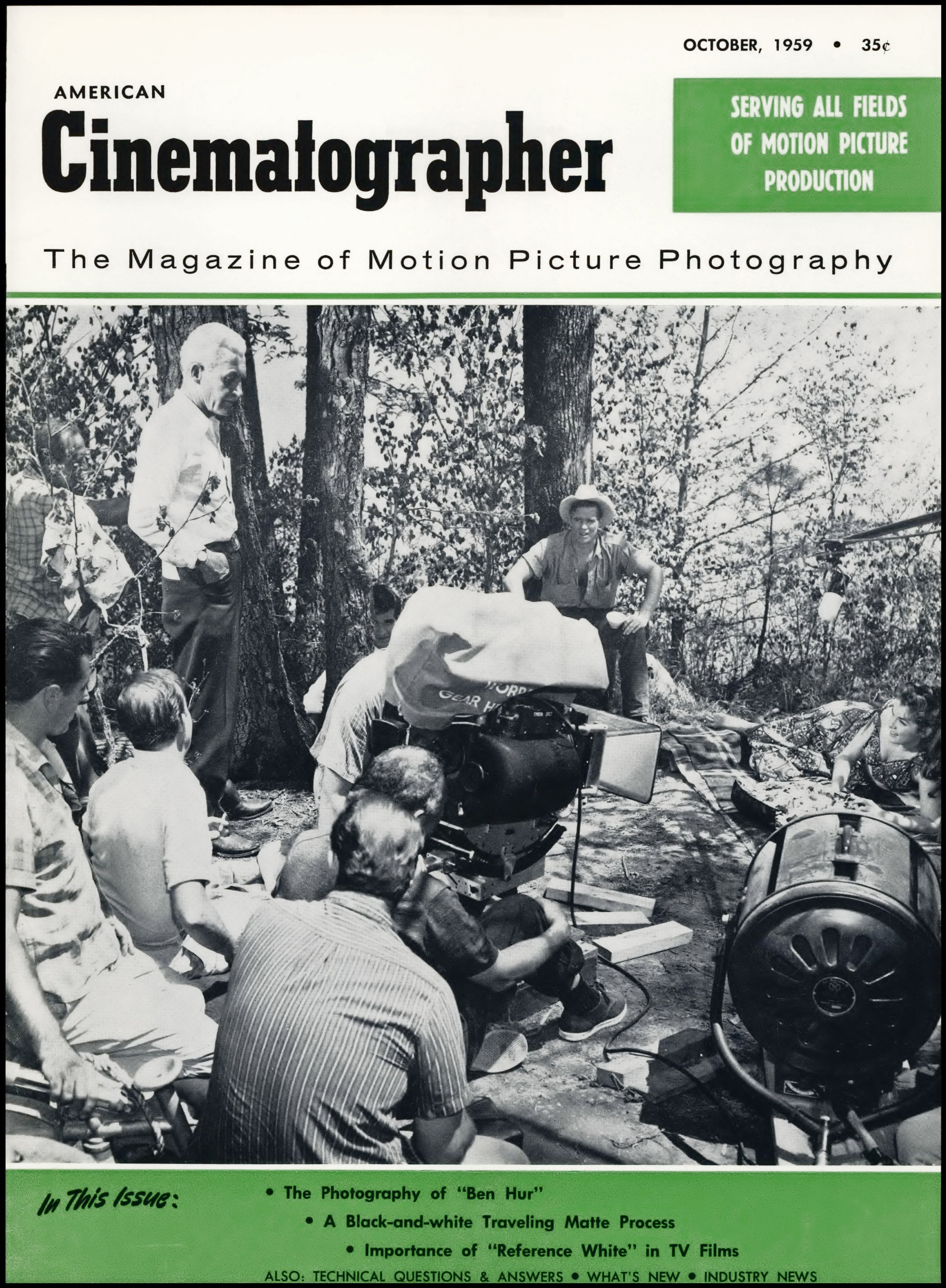

The Photography of Ben-Hur

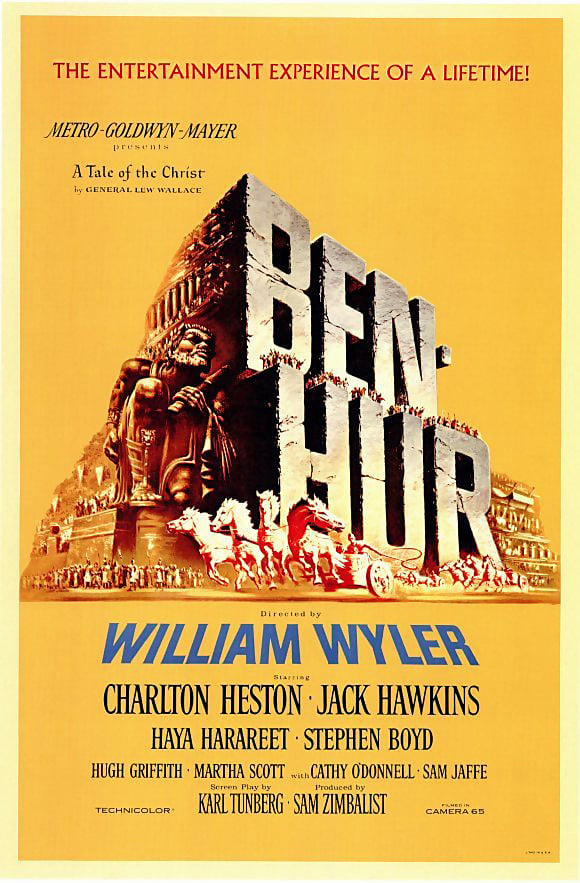

Go behind the scenes of this Oscar-winning Biblical epic that set new standards for lavish production — captured in anamorphic 65mm by Robert L. Surtees, ASC.

AC’s original coverage on this epic period drama was spread over two issues. Both feature stories are presented below.

The Photography of Ben-Hur

By Libero Grandi

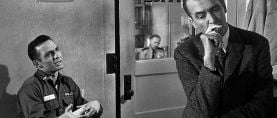

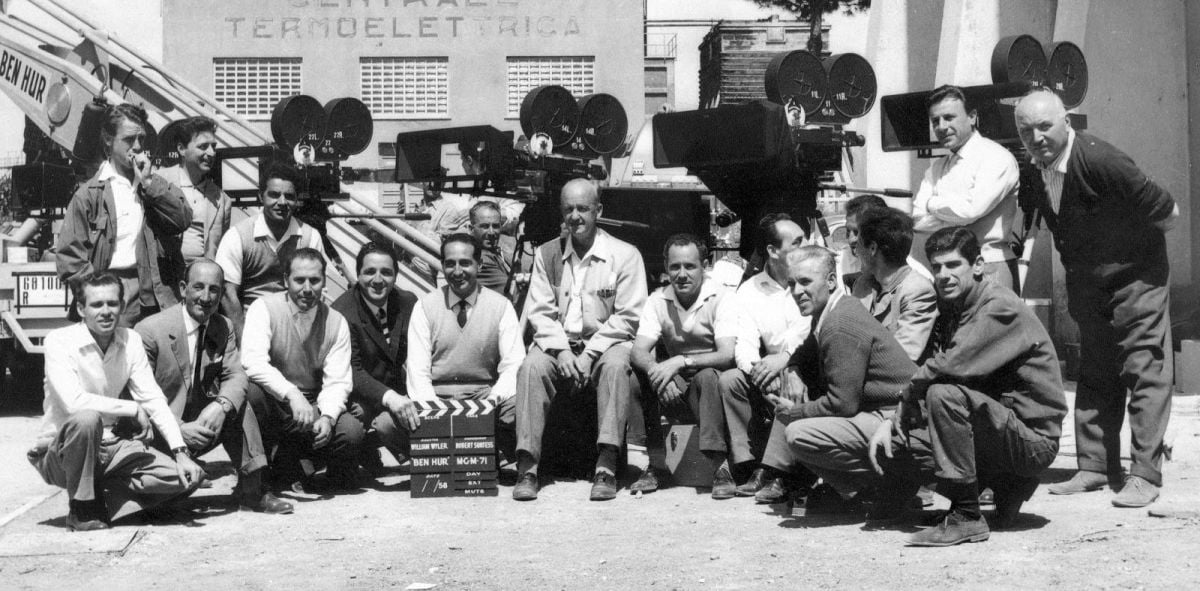

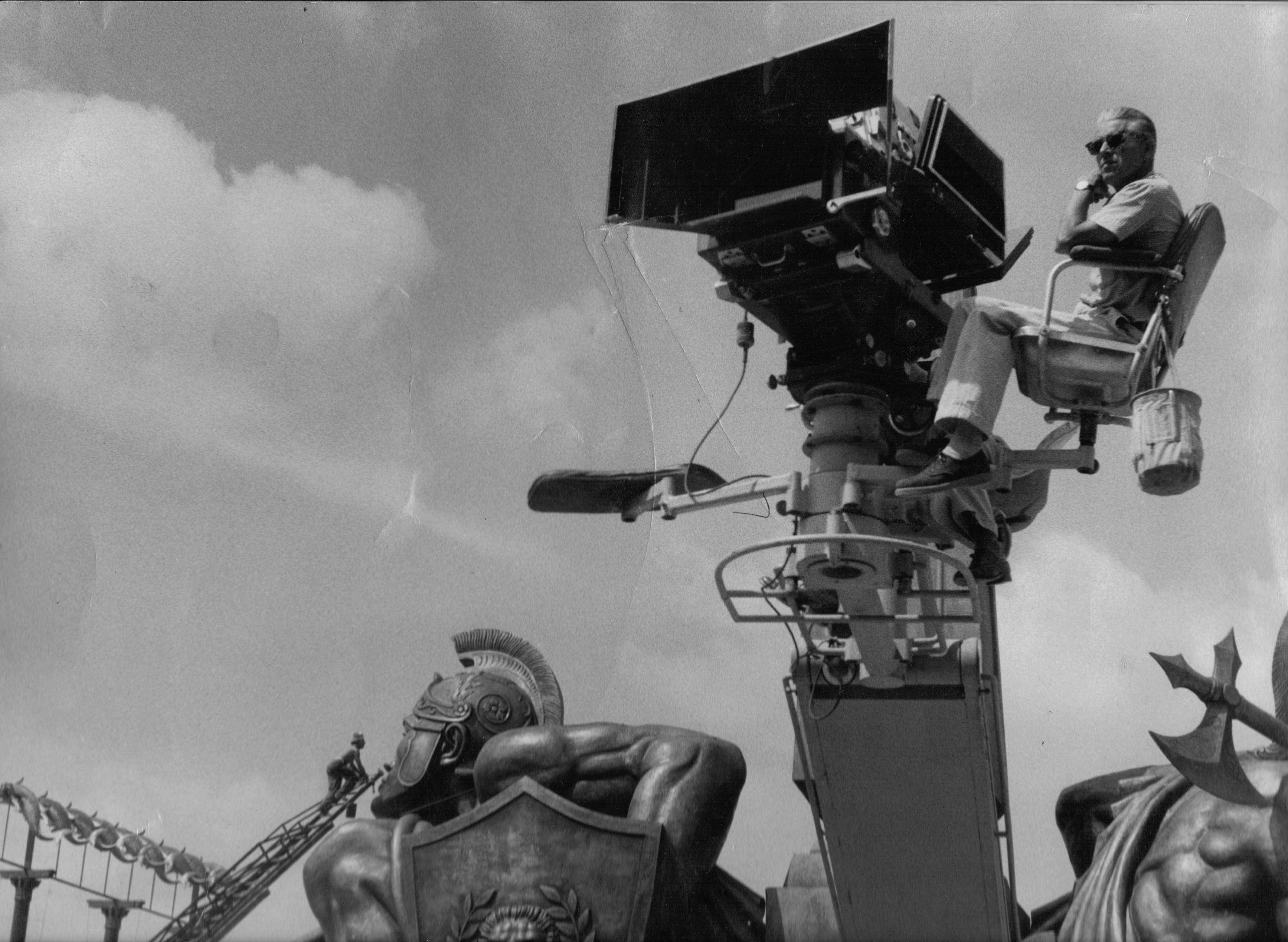

MGM’s multi-million dollar production was photographed entirely in Italy on 65mm Eastman Color film with Panavision cameras and lenses by three camera crews supervised by Robert Surtees, ASC.

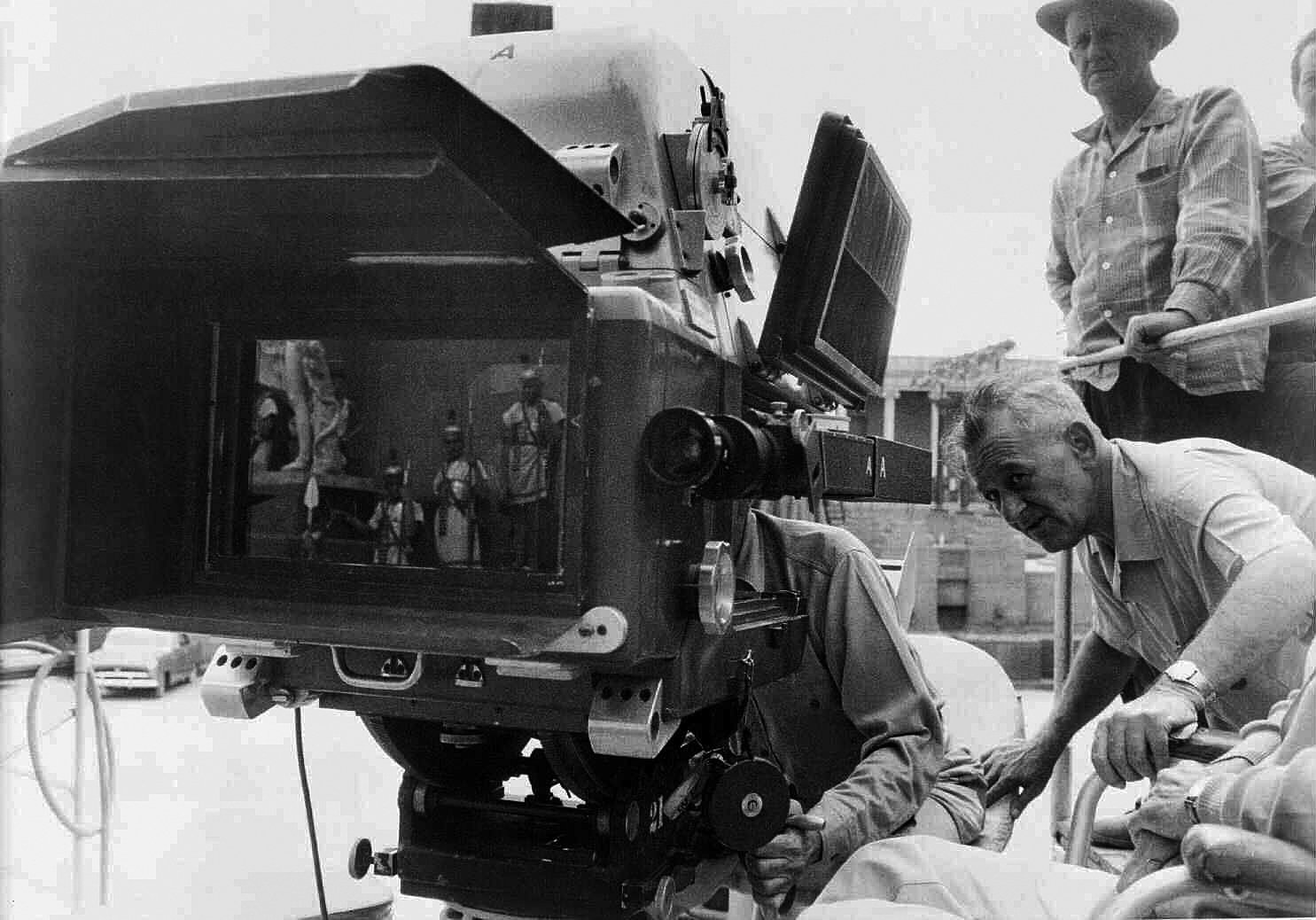

According to Robert Surtees, ASC, who directed the photography of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s Ben-Hur in Italy, over one million feet of Eastman Color 65mm negative was exposed there for the production. A total of six Panavision 65mm cameras were shipped to Rome by the studio, and often all of them were shooting at the same time on large spectacle scenes, such as the chariot race.

The monumental undertaking of photographing Ben-Hur in Italy had been carefully planned in advance during cooperative pre-production meetings attended by Surtees, director William Wyler, the screenwriter, art director and costumer.

Shooting with the wider 65mm negative, Surtees explained, involved virtually a trebling of efforts as against shooting in 35mm. In composing scenes for the wider picture format, great care had to be taken with the lighting because the extreme sharp rendition obtained with Panavision lenses brings to the screen with exceptional clarity every detail in fabrics, costumes and props as well as any irregularities in facial features or application of makeup. Successful photographic results were assured through the cooperative efforts of MGM’s costume and makeup departments which planned their phases of operation to accommodate the photography in every possible way.

The Panavision wide-angle lenses used were 57mm. These were employed mostly for two-shots and closeups. On some two-shots, as where one person stood slightly ahead of or behind the other, it was difficult to keep both subjects in sharp focus with this lens. Here the problem was solved by focusing sharply on the most important of the two persons and adjusting the lighting on the other – taking care that the colors in the latter’s costume were complementary to that of the important subject’s dress. The effect on the screen is sort of equalization of focus on both subjects. Except in those cases where extreme split-focus was desired, Surtees invariably used small f/stops and intensified lighting.

As MGM plans to release Ben-Hur in both 65mm and 35mm, it was necessary, Surtees said, to consider this at all times when composing scenes in the camera finder. Whenever compositional requirements for the 35mm picture format conflicted with those for the more important 65mm, however, the scene was invariably composed for the latter.

An ever-present problem during the filming of Ben-Hur was maintaining a vigilant check on the color temperature of the light. And because shooting in Rome extended from May until December, it was necessary to aim for consistency in color temperature, so scenes shot in May would look no different than those shot in December, when days were shorter and the sun closer to the horizon.

Surtees found the color temperature of sunlight quite variable. In Rome, especially, the luminosity is intensive, yet is often characterized by sharp changes that take place within only a few hours. Extensive tests of light conditions were made, after which the necessary corrective filters were ordered for use on all of the Panavision camera. It was Surtees’ aim to produce negatives so precisely color-balanced that the film laboratory’s task in correcting for color would be reduced to a minimum and result in prints approximating his expectations.

When making color temperature tests, Surtees used the Spectra color temperature meter. With this instrument he was able to calculate various combinations of colors in rapport with the Kelvin scale, adding or subtracting color when necessary. He thus was able to arrive at a norm through use of the designated corrective filters. With the aid of this meter, for example, Surtees determined the exposure and filter to use in order to make a “sunset” shot at high noon.

In a similar way he solved the problems resulting from any deviation in the color temperature of light on actors’ faces, where complexions had changed because of exposure to sun and wind. Such color temperature checks enabled Surtees to decide when a makeup should be changed and how much.

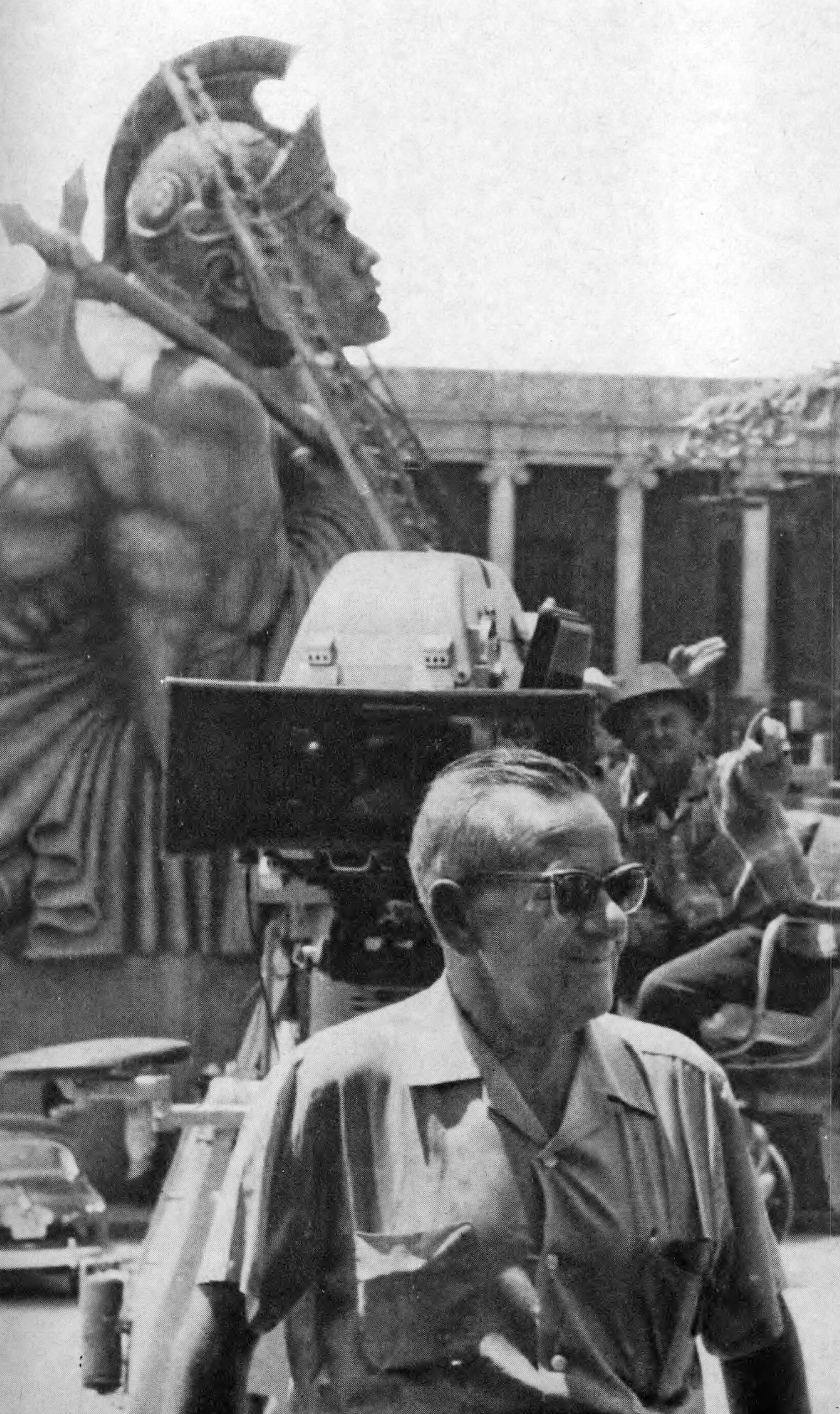

As the available Kodak CT filters were not entirely adequate to meet, in the additive color film process, the variations of color temperature under Italian skies, Surtees did some personal research with the view of combining certain Kodak CT filters with those of Photo Research Corp. To facilitate this step, the equivalent values of Kodak and Photo Research CT filters were determined as follows:

Thus, when at 9:45 a.m. the CT meter indicated in the blue/red range and 6 in the green/red range, this added up to a color temperature of 5480°K. The meter chart showed that this required a 1T filter for the blue/red, and none at all for the green/red range where color temperature was normal. Translating the meter calibration, 1T indicated that a Kodak 82 filter would have to be combined with the normal 85 filter for proper color results at that time of day.

At 12 o’clock noon on the same day, the sunlight registered the normal 5700°K on the CT meter, which required the user of only the 85 filter on the camera lens. But at 2:45 p.m., another meter reading indicated the color temperature of the daylight had declined to 5195°K. This called for using a Spectra 2T filter (or its equivalent, the Kodak 82A) in combination with the 85.

As with the studio’s earlier production of Ben-Hur many years earlier, the 1958-’59 version was turned out by a production company divided into three units for flexibility and speed. Director William Wyler and cinematographer Bob Surtees, heading the first unit, photographed most of the interiors for the picture and also supervised units 1 and 2. Director Andrew Marton and Italian cinematographer Piero Portalupi headed the second unit, which concentrated on filming the chariot race sequence for the picture. The third unit was in charge of director Richard Thorpe and cinematographer Harold E. Wellman, ASC. This unit photographed the fight action scenes on the galleys, some of the chariot race scenes and did some retakes for the other two units.

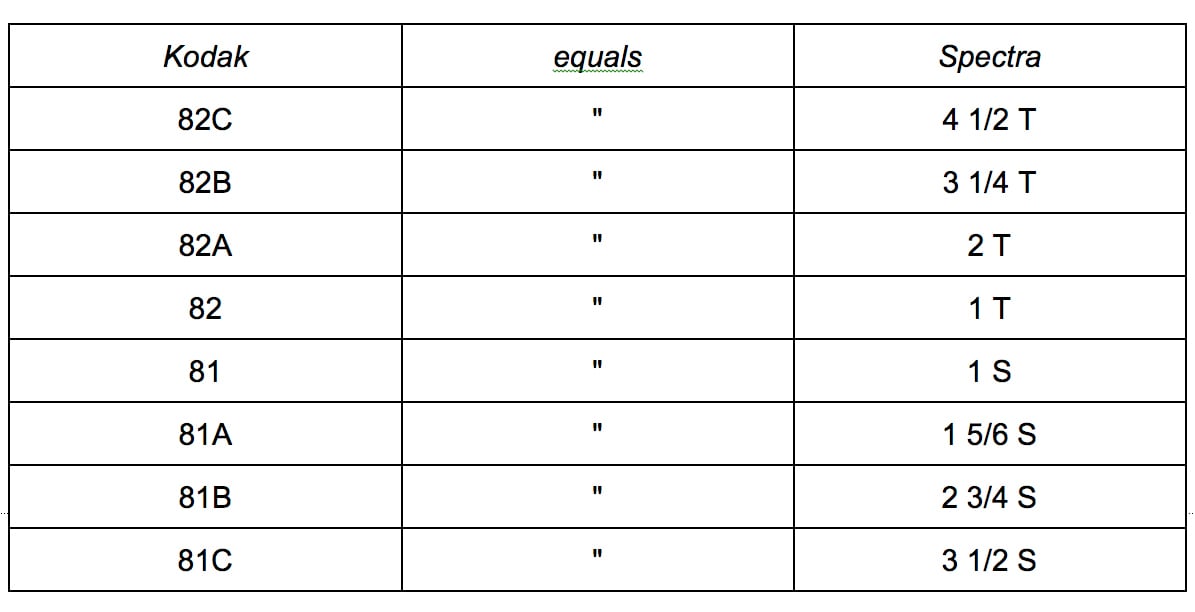

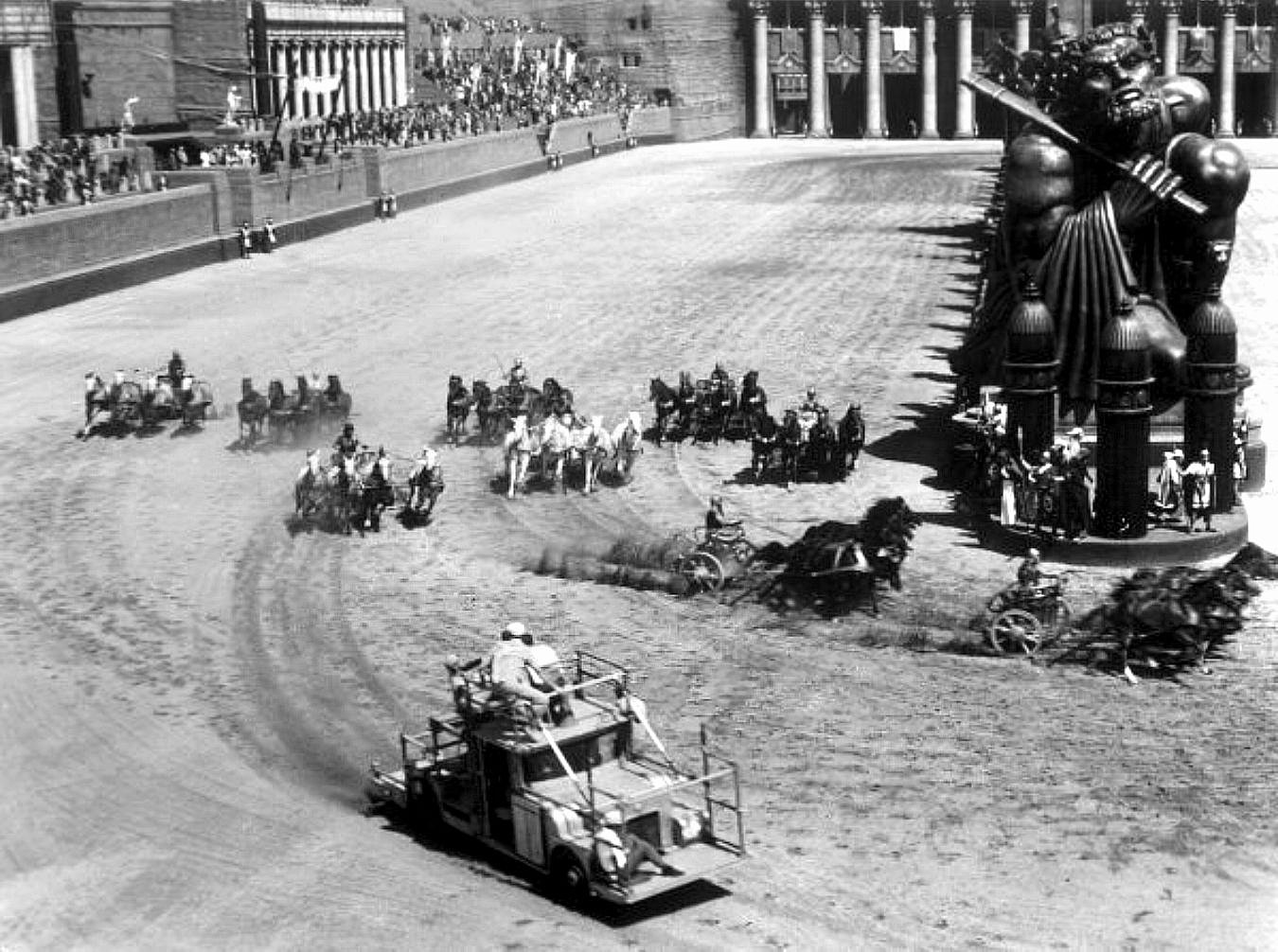

The chariot race is perhaps the most dramatic action sequence in the entire picture, climaxing as it does, the terrific struggle between the two antagonists, Messala and Ben-Hur. Altogether, five months were spent in shooting the chariot race scenes for a sequence that will run less than 40 minutes on the screen.

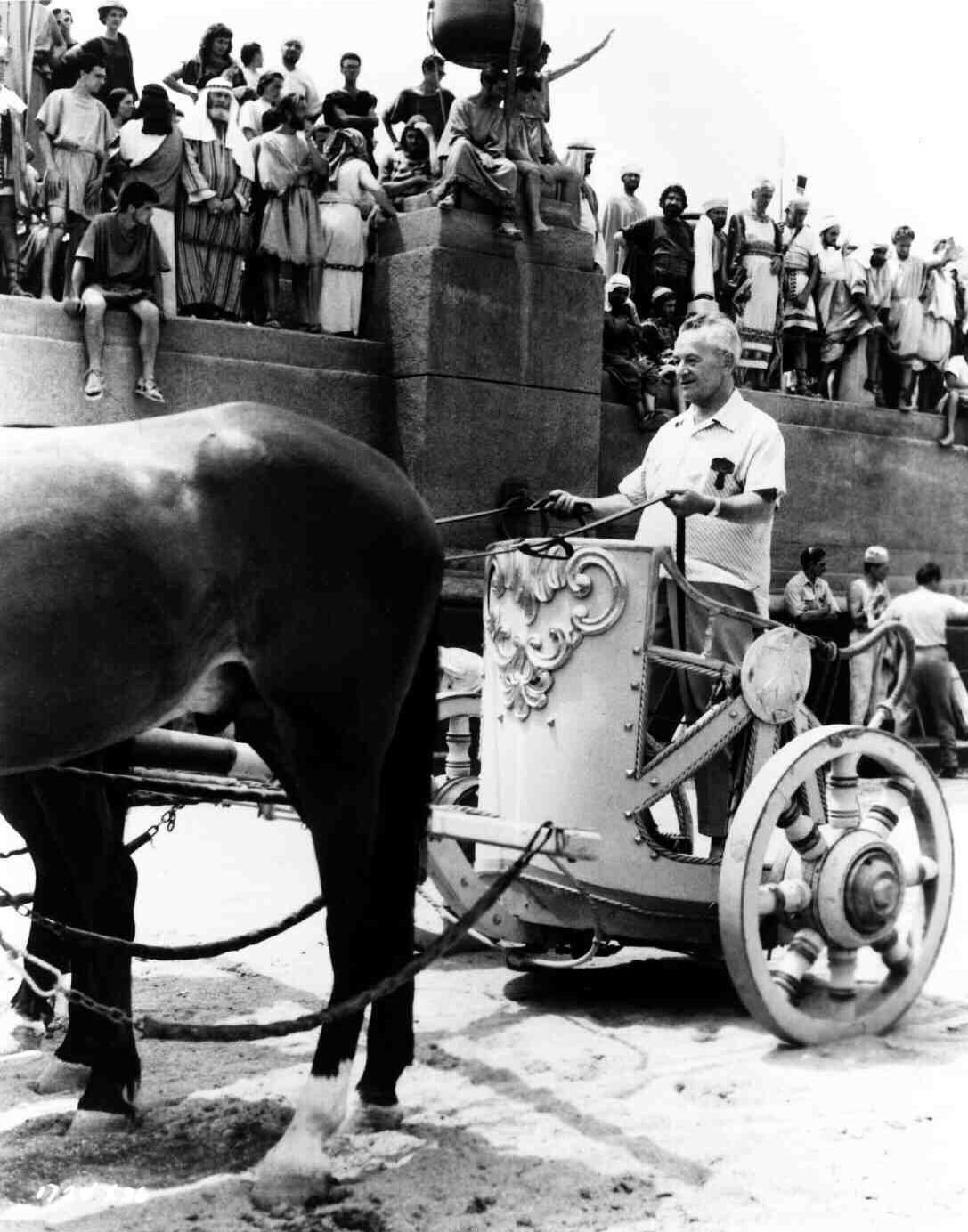

To take advantage of the predominantly sunny days of the Italian summer, Portalupi and his camera crew worked steadily from 6:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily. Two and sometimes as many as four Panavision 65 cameras were set up at strategic places around the Roman Circus set where the race was staged. The cameramen handling the secondary cameras were directed by Portalupi by radio intercom, while Portalupi and his crew photographed the master shots.

The traveling shots of race action, made with the camera mounted on a speedy camera car, were the most difficult to make, according to Portalupi. Despite the fact that the car was powered by a 300 h.p. engine and the Circus track was smoothed and watered down after every take, the camera car unavoidably slipped into the furrows made by the chariot wheels on their first turn around the track.

There was another problem, too. When shooting from the camera car, as it circled the track, the lighting had to be compensated for, as it would change progressively from, say, flat lighting to cross- or back-light as the camera car traversed its oval course. As far as possible, this situation was minimized by altering the lens to stop during a run to conform with the light, with exposures ranging between f/5.6 and f/11.

Color temperature changes also had to be compensated. A constant check on the light was made throughout the day and the necessary color correction filters employed when necessary.

To produce in the photography the illusion of great speed in chariot travel during the racing action, it was decided, after shooting a number of tests and screening them, to photograph these scenes at the slightly reduced speed of 20 f.p.s. instead of 24.

“When we were making chariot-race shots from a fixed position,” said Portalupi, “where the chariots were charging directly toward the camera, it was observed that the effect of speed was greatly reduced; so we reduced the camera speed further, to 16 f.p.s., then gradually increased it to 20 f.p.s. again as the camera, now panning, followed the chariots and caught them going away. No such problem was faced when making the traveling shots of the race, however, as the camera car usually traveled at the same speed as the chariots.”

Both Portalupi and director Marton were further guided in staging and shooting the chariot race scenes by a series of storyboard drawings furnished to them by the studio. Also, they studied at great length the chariot race scenes in the first Ben-Hur picture, which the studio made many years ago.

“We duplicated almost to the letter one scene in the original film, which seemed to us a most powerful one visually in spite of the passage of time,” said Portalupi. “This was a pan shot made from a high elevation, with the camera following the chariots as they approached a turn around the Spina. (The Spina is a long, narrow platform accommodating spectators in the center of the Circus area. — Ed.)

To make this shot, the camera was mounted on one of two iron towers, which were about a hundred feet in height and built to provide the necessary elevation for another camera that was used to make matte shots. The camera was mounted at a height of about 50 feet and at an angle of 45 degrees; it looked down upon one of the massive statues mounted on the Spina and provided a wonderful, unique view of the whole racing event.

Cinematographer Wellman was assigned to shoot the fight sequences on the galleys. Like Surtees and Portalupi, he also employed two or more Panavision 65 cameras for all key shots of action scenes. This sequence was shot in and on “the tank” on the Cinecitta Studio lot in Rome. More than 600 actors and extras were employed in these scenes, according to Wellman, and the galleys were authentic replicas of the historic craft described in the famous [1880] novel “Ben-Hur.”

To achieve the most dramatic effect pictorially, it was decided to give the encounter the aspect of taking place at dawn, which called for predominately low-key lighting. Here frequent color temperature checks were vital to insure scenes that would integrate perfectly with the rest of the picture.

Prior to going to Rome for this assignment, Wellman shot all of the miniatures required for the galley fight sequence on the “lake” on MGM’s backlot in Culver City.

Since completion of the photography of Ben-Hur, the cutting, editing and dubbing of the vast amount of footage shot in Italy has been going on at a feverish pace so that the picture will be ready for its world premiere sometime in November.

Bob Surtees has remained in Europe where he has enjoyed a well-earned vacation. Not content with being idle long, however, he recently undertook an assignment to direct the photography of Bay of Naples in Italy for Paramount Pictures, on loan-out from MGM.

The article beginning on this page is a fitting sequel to Libero Grandi’s story “The Photography of Ben-Hur,” which appeared in our October issue. It describes in excellent detail the problems that were encountered in staging and photographing what is considered the most thrilling motion-picture action sequence of all time. It is reprinted here by permission of Films In Review, for whose January, 1960, issue it was written by director Andrew Marton. — Editor

Filming the Chariot Race for

Ben-Hur

By Andrew Marton

The man who directed the most thrilling sequence for MGM’s great epic describes the many problems encountered in photographing it.

The late [producer] Sam Zimbalist was a close and respected friend and when he asked me to stage and direct the chariot race sequence for Ben-Hur, I had mixed feelings. It was a challenge, but it also meant anonymity, in accordance with the motion picture industry’s archaic rules for screen credits.

I had been disappointed before. I directed the mountain battle scenes in David O. Selznick’s A Farewell to Arms and was “lavishly” rewarded with a screen credit which read in effect: “Many thanks to Andrew Marton for his valuable contribution.” What contribution? Audiences never knew.

However, the challenge of Ben-Hur’s chariot race was there. Zimbalist was there. And William Wyler, whom I respect greatly, was there. I had directed a sequence for Wyler before — the so-called “Dunkirk” sequence in Mrs. Miniver.

So I said: “Let’s go.”

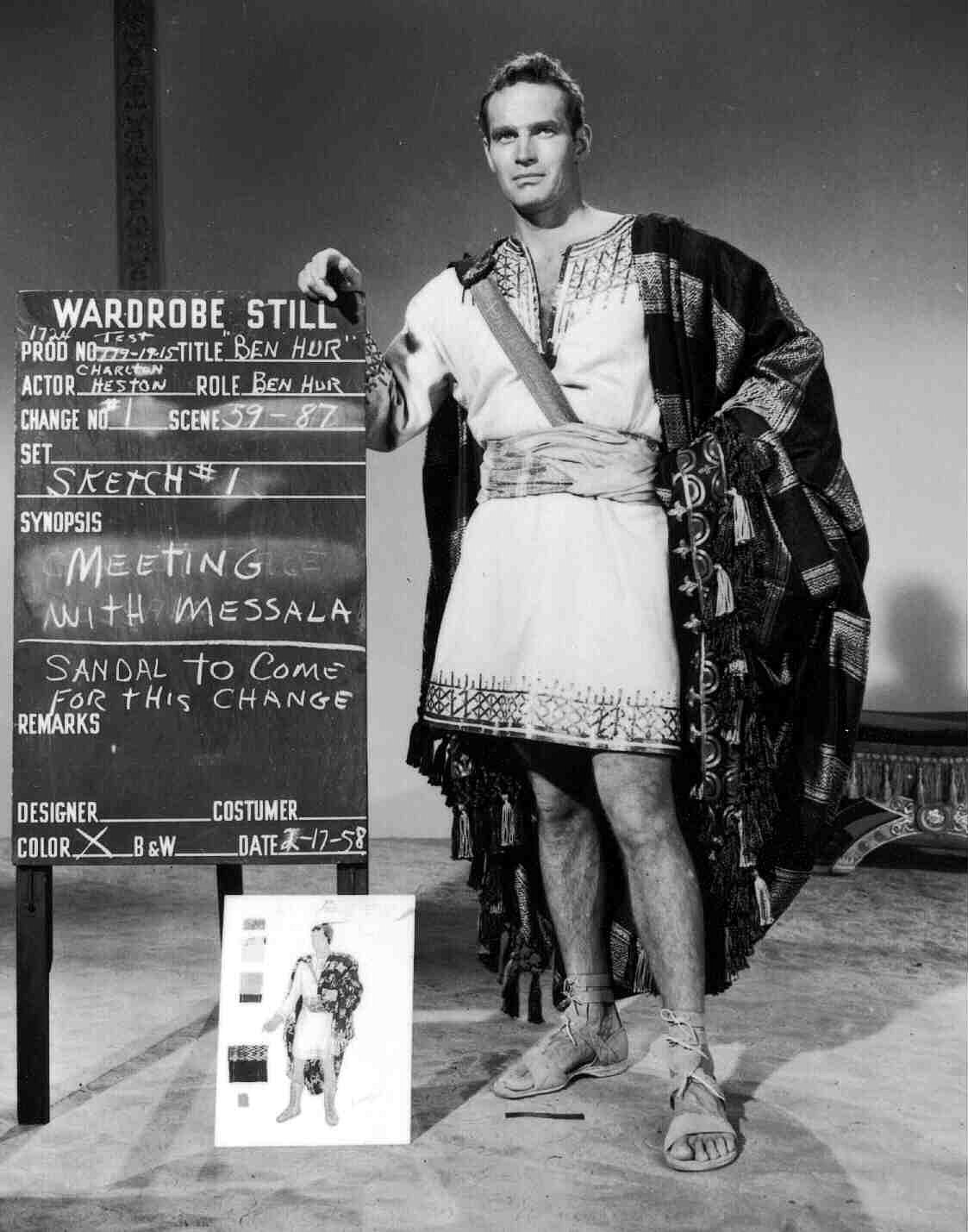

Zimbalist gave me carte blanche, except for one warning. It was not to be just a race, but a race to the death that carried the implacable hatred of Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) and Messala (Stephen Boyd) to its logical conclusion. The problem was not who wins the race, but who stays alive. In other words, Zimbalist waned the most exciting and dangerous race ever — BUT. His one warning: If anything happened to Heston or Boyd, there would be no picture.

MGM started building the arena for the race in January ’58 at the Cinecitta Studios in Rome. Since the arena in the story is in Jerusalem, its architecture was not Roman, but more barbaric and primitive. Only this one arena was needed, since the film does not show how Ben-Hur, during his stay in Rome, got to be an expert charioteer. We do see him near Jerusalem criticizing the training of some Arabian horses intended for the race. But the first time we see him in a chariot is when he enters the arena for the race.

While this huge set was being built we hunted for suitable horses – and matching teams, which were essential. The race was to be run by nine chariots drawn by four horses each, but since certain teams had to be duplicated, and there had to be “understudy” teams for the “star” teams, we required 82 horses of the proper physique, and harmonious colors. Horses can go lame, and anything can happen in a race.

The horses were finally obtained in Yugoslavia and in late January we began active preparations for the filming of the race. Actual shooting was to be in May and June.

In order not to interfere with the building of the arena, an identical track was built adjoining it so we could start training horses and chariot riders, and lay out camera shots.

The surfacing of the race track proved to be a troublesome problem. Research in Roman libraries turned up nothing on the composition of the surfacing of the race tracks of two millennia ago. The surface of our track had to be hard enough to hold the careening chariots and horses, had to have a drainage system in case of rain, and had to have a sanded top, because cement would lame the horses.

So we started with ground rock debris, which had to be steam-rolled. That was covered with 10 inches of ground lava — against my and Yakima Canutt’s judgment — and that was covered with 8 inches of crushed yellow rock.

This lasted only one day when actual shooting began. It was used only in the first long shots, in which there were 6,000 extras. The horses were slowed so much we almost wasted the entire day’s work — a day on which 6,000 extras were paid to watch the race. We removed the crushed yellow rock and left only a 1 ½ inch layer of lava. This worked fine — and even enabled the chariots to skid around the corners.

While the set was being built and the surfacing worked out, the Yugoslavian horses underwent a spectacular change. They began to fill out, their ears perked up, their nostrils began to flare, and stubborn individual farm horses began to be cooperating teams of four. The credit for this belongs to trainer Glenn Randall, who even had to teach the horses to react to commands and reining different from the ones they had been used to all their lives. I still don’t know how Randall turned them into race horses. Consider only the staling of all those horses — the grooming, feeding, shoeing and keeping them healthy.

The drivers were mostly the elite of stunt and rodeo riders from the U.S., but there were also some Italians. The charioteers began training as early as February, as did Heston and Boyd. The former had the easier time, for he was experienced in Westerns and has strong hands and tremendous shoulder muscles. Boyd’s hands became blistered and bloody. We tried to loop the reins around his wrists, but that didn’t help, for his wrists also chafed. We tried quite a few chemicals and ointments to toughen up his hands. At times, he had to stop practicing for a day or so to allow his hands to rest.

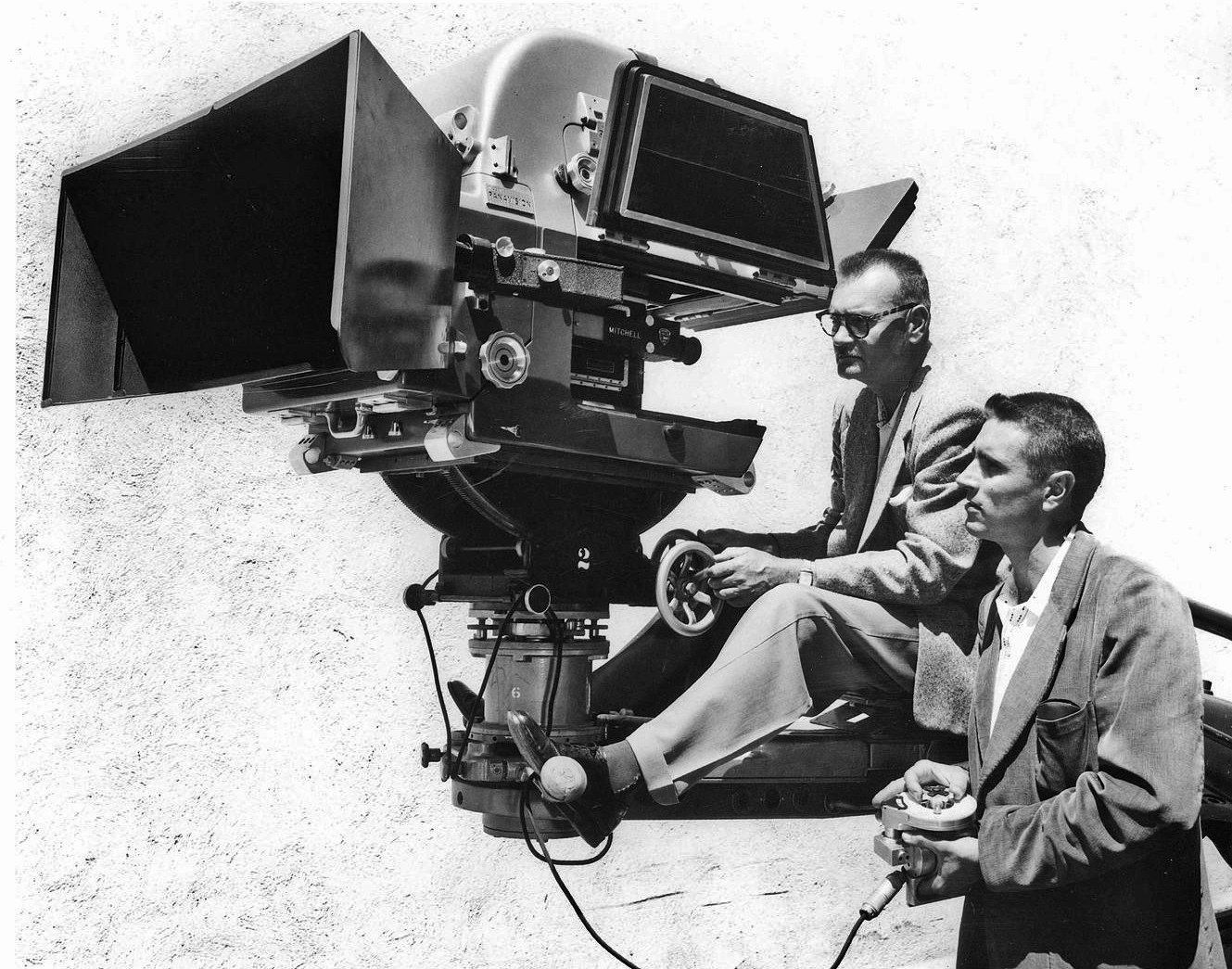

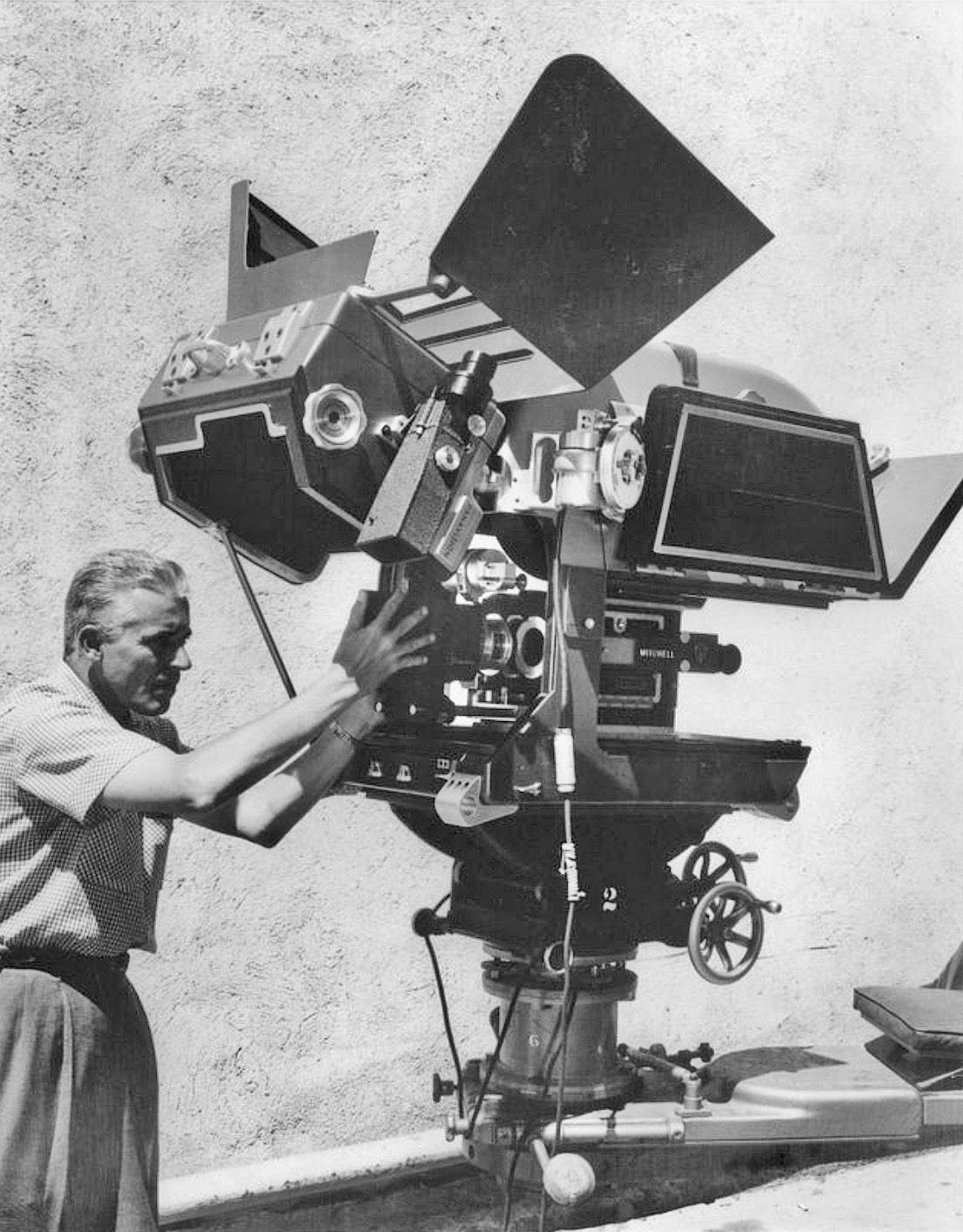

Three 65mm Cameras Used

I had three 65mm cameras at my disposal at all times during the shooting of the race. Except for one standby in Culver City, there were only two other 65mm cameras in Rome — in fact, in the world. The other two in Rome, of course, were used by William Wyler.

The limitations these new cameras impose quickly became apparent. The best lens to use with a 35mm film for a closeup of a charioteer that retains the horses in the picture, is a 4-inch lens (also called a 100mm lens). The equivalent of a 100mm lens in the 65mm medium is a 200mm lens. But the 200 could not be focused closer than 50 feet, and I had to get closer than 50 feet in order to get a good dramatic closeup. So I used a 140mm lens instead and moved closer to the horses, the hooves and the danger. For certain scenes, we archived the effect of the horses stepping on the camera car!

Heston and Boyd did all the chariot driving they seem to be doing except for two stunts. We tried out one scene with a dummy being dragged by a chariot. It didn’t work. Boyd looked at the ripped and torn dummy, and asked: “Me?” I nodded. He shrugged and did it. We protected him with some steel coverings here and there on his body, but he still was bruised and abrased. However, we got a real and untricked closeup of Boyd being dragged under his own chariot.

Despite the best of precautions, accidents did occur.

Chariots Smashed Cameras

The best position to photograph a curve is at the far end as the chariots swing out of the curve. Once two chariots smashed into two of our cameras when they came out of the turn too fast. Fortunately, no horses were lost, or even lamed, and the crew and cameras were only bruised, thanks to a heavy wooden barricade we had the foresight to erect. But the production schedule really suffered. The cameras had to be repaired and tested before we could use them again, which took several days.

One simple shot turned into a nightmare. It was a fast moving shot, but since it was a straight run and did not swing around the corners I did not expect any complications. It went this way: The camera car was followed by Heston and Boyd, at full speed, and their chariots were followed by the seven other chariots. We were in the middle of the fastest run when suddenly the motor of the camera car backfired, stuttered and died, and there we were in front of the onrushing Heston-Boyd horses, chariots, etc. I could not help recalling Zimbalist’s warning when I had insisted that for realism we had to have Heston and Boyd in these shots: “If you curl one hair on their heads!”

The fine Yugoslavian horses saved the day. They swerved and missed us — and all nine chariots. If any of those horses had split opinions, two going one way and two the other — but they didn’t.

One of the stunts in which we used a double for Heston was as follows: We had established for the audience the fact that when a crash occurs during the chariot race workers rush out and clear the track. But when Boyd causes two chariots to go down in a spectacular double crash the workers were unable to clear the wrecked chariots off the track before Heston and Boyd complete another lap and head down the straightaway toward the wreckage. Realizing his advantage, Boyd forces Heston directly into the path of the crashed chariots. There seems to be no escape — Heston either has to pull up and lose the race, or try to take his horses and chariots over the seemingly insurmountable obstacle.

The stunt was easy to put on paper, but not all easy to put on film.

Yet, it was done. Yakima Canutt, who was wonderful in his rigging of the falls in Ben-Hur, allowed his son, Joe, to double for Heston in this stunt. Joe is 22 and an excellent stuntman, but perhaps a little too eager. Anyway, he started out toward the wreck at great speed and Yak and I, in one voice, screamed: “Too fast, too fast!”

Thrill Scene Unplanned

Joe, of course, could not hear us, and was committed. The four horses sailed over the wreck beautifully, but when the chariot came down it hit hard and bounced. Chariot and charioteer sailed into the air. When the chariot landed again Joe was flipped into a hand-stand and thrown out between the horses. He instinctively grabbed the cross-bar between the horses, but nevertheless he was dragged some feet.

We rushed him to our emergency hospital just outside the track and a few minutes later I heard a tremendous roar from the crowd. I look around and saw young Canutt, with only a cut on his chin (four stitches), returning to work.

His is the most spectacular stunt I have ever seen. It will do for him what the Stagecoach stunt — jumping between the horses — did for his father.

Naturally, the script was re-written to allow Heston to repeat the falling out of the chariot in a close shot and then to swing himself back up and go on to win the race.

In our search for new angles we tried to get the camera under a chariot, but flying dirt thrown up by the horses’ hooves kept covering the lenses. We mounted the camera behind Heston and tried to shoot over his shoulder. I found the flying dirt so heavy I had to hold a small piece of plywood over the lens until the chariots reached their fastest speed. Then I uncovered the lens for ten seconds — until the lens was blotted out again — I was able to get a shot.

There are seven laps in the race and my detailed script for the race had six pages for each lap. Each stunt, each over-taking by Heston or Boyd, each crash, was carefully planned. Each had to take place within 23 seconds after the run started, since it took that number of seconds to run the length of the track. If a particular scene had to happen on a curve, the time allotted was even shorter.

Moving Camera Shots

After the first few days we found that, because of the arena’s size, the most effective shots were the ones for which the camera moved with the race and in the race. I decided, therefore, that once the flag was down and the race began, we should participate in the race with our lens. This, of course, necessitated a rethinking of the race, as well as a rescheduling.

We did not have an actual shooting schedule. Zimbalist’s orders were to make the race as good as was humanly and humanely possible. I made it as good as I humanly could in 10 weeks shooting time, and also made it humanely — without the loss of a single horse or man.

Our concept of how the race should be shot somewhat resembled a musical score in that there were constant crescendos and de-crescendos.

The going around the end-curves required the camera operators – both of them Italians – to compensate for the centrifugal force encountered in the curves. The best shots on the curves were achieved not by the camera car but a specially built rubber-tired and independently sprung camera-chariot.

The heat of Rome was a serious handicap, for the horses could take only seven or eight runs a day. Each run had to be planned in detail if we were to finish the race at all with an average of only seven takes a day! Because of this, almost all scenes were done in one take. The only shot I did over was the one in which Heston’s chariot runs over a centurion. At the critical moment one of the chariots got in between the lens and the falling warrior, blotting out the action.

The most difficult shot?

Toward the end of the race — when the wheels of Heston’s and Boyd’s chariots are interlocked, and Boyd starts to whip Heston.

In order to show the immediate danger in which they were, I decided to pan from the interlocking and splintering wheels to the two antagonists in vicious combat. To get this effect we had to chain the camera car to the two chariots. I didn’t have time to realize that if one horse stumbled, the whole contraption – horses, chariots, stars, camera-car – would crash and pile up in disaster.

A pessimist, or merely a worrier, could never had directed this chariot race. And nobody could have done it without the help of MGM’s prop shop and special effects department.

I have been asked how the staging and directing of the Ben-Hur chariot race differ from those of the exodus from Dunkirk in Mrs. Miniver and the mountain battle scenes in A Farewell to Arms. It is in the number of separate shots. To my knowledge, never before in one motion picture were there so many short cuts in a sequence of 11 minutes duration. Some of the cuts are only a foot or a foot-and-a-half of film!

I was deeply gratified when William Wyler told me he thought the chariot race was one of the greatest cinematic achievements.

But I didn’t feel so good when I saw the screen credits. I share a credit-card with, I believe, five other people and am listed as one of three “second-unit directors” — the minimum credit requirement stipulated by my contract with MGM.

I cannot help thinking that if Sam Zimbalist had lived, I would have received the simple credit I wanted: “Chariot race directed by Andrew Marton.”

Nevertheless, if today someone asked me to tackle a similar cinematic challenge, I’d again say: “Let’s go.”

Marton’s subsequent credits as a second-unit director include Cleopatra, The Fall of the Roman Empire, Kelly’s Heroes, Catch-22 and The Day of the Jackal.

Ben-Hur would go on to become a worldwide a box-office and critical success, earning 11 Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Cinematography (Color).

In 2004, Ben-Hur was added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.