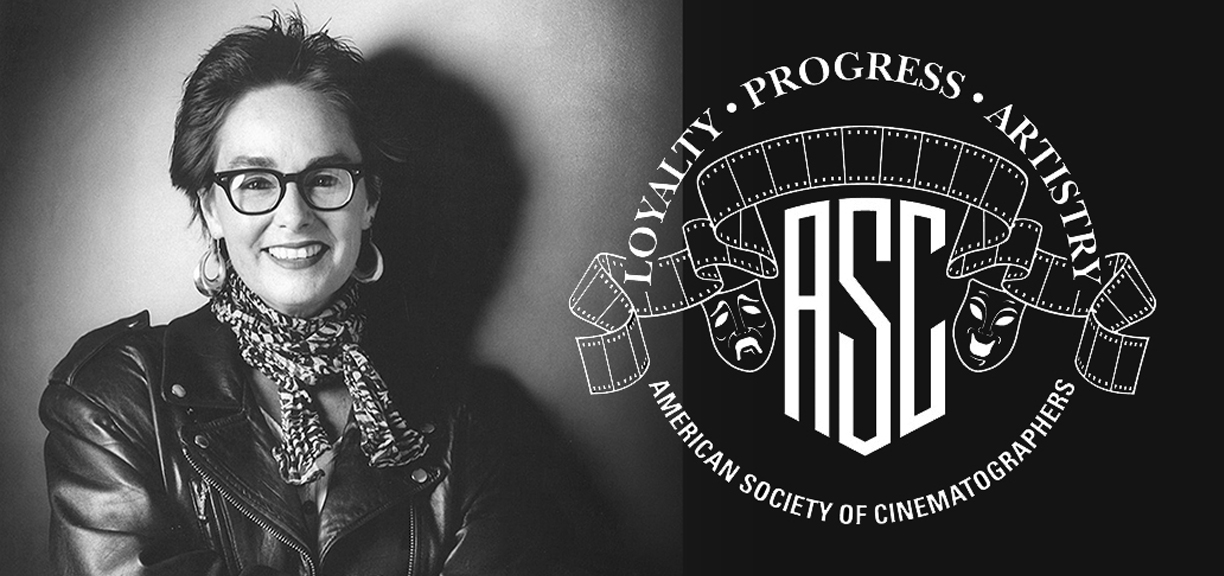

In Memoriam: Judy Irola, ASC (1943-2021)

The cinematographer, documentarian and educator died Feb. 21, 2021, at the age of 76, leaving behind a legacy of artistry, tenacity and inspiration.

Born in rural Fresno, Calif., on Nov. 23, 1943, Judith Carol Irola grew up with the desire to pursue her passions.

Her grandparents had emigrated from the Basque region to Fresno in 1917 to escape poverty. They founded a sheep ranch and connected with a strong community of other Basque expats. Irola’s parents, Barbara and Johnny, married in 1942 and had three daughters: Judy, Jeanne and Barbara Jo. The eldest, Judy displayed an adventurous spirit by frequently accompanying her father to their sheep camps in the mountains. She later chronicled this history in a 2014 documentary short, The Sheepherder’s Daughters, constructed largely from the family’s 8mm home movies and Brownie camera stills.

Irola’s interest in motion pictures began in childhood, as she and her sisters spent Saturdays at the local movie theater watching shorts and features that frequently starred Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. A compulsory Catholic-school trip to see The Ten Commandments also left a lasting impression.

After graduating from high school, she briefly studied at a state college, but she was not inspired and dropped out — much to the displeasure of her parents. Seeking independence, she enrolled at the Central California Commercial College, where she learned secretarial skills, and then sought to live abroad. She worked as a secretary in London, and then as a librarian at a U.S. Air Force base outside Seville, Spain.

In 1965, a friend told Irola about the newly formed U.S. Peace Corps, and she enthusiastically joined the effort, seeking to put her office skills to better use. After three months of training in California, she served alongside 64 other idealists for two years in the African nation of Niger. They worked to improve water and sanitation systems, build schools and provide vital health education; the latter became Irola’s primary work. “My experience [there] influenced the rest of my life,” she later told AC correspondent Bob Fisher. “Realizing that poor people can have extraordinary love for their families and not wallow in self-pity, but instead [be] proud of their contribution to their communities, was a big awakening.”

“In the United States, we were told that we were going to ‘save the downtrodden of the world,’” she continued. “Instead, living with these beautiful people side-by-side in their villages helped us to see the dignity in all people, and forced us to fall in love with a beautiful country, no matter how poor it was. None of us ever saw the world in the same way again.”

Irola recounted these experiences in her documentary Niger ’66 — A Peace Corps Diary (2010), for which she not only returned to the remote village where she had been stationed, but also reconnected with many of her fellow volunteers to re-examine their goals, efforts and accomplishments.

“We came home to a different world in 1968,” Irola noted. “There were anti-Vietnam War demonstrations; Gloria Steinem had launched the Women’s Liberation Movement, and the Black Panthers were actively engaged in civil-rights issues.”

Returning to the Bay Area, she found work as a secretary at KQED-TV, the local PBS affiliate in San Francisco. “As I sat at my desk, I watched the people come out of the film department carrying silver cases and wearing Levis, and I didn’t want to wear nylons anymore — truly — so I started working with the film department on weekends,” she recalled in Jon Fauer, ASC’s documentary Cinematographer Style (2005). During those days of on-the-job training, she learned the basics of how to load and operate a 16mm Éclair NPR camera and shoot news and documentaries, giving her experience as a camera assistant, editorial assistant and all-around production crew member. With funding soon secured for a major PBS documentary series, Irola was transferred into the film department, given additional training and then hired as a full-time cameraperson.

One of the few women cinematographers working at the time, Irola co-founded National Alliance of Broadcast Employees and Technicians 532, a non-IA local representing Bay Area film workers in technical crafts, including camera, editing, lighting, sound, makeup and art direction, in 1969. Starting as a shop steward, she later became its president. “I’m a union girl,” she told Alexis Krasilovsky for the 1997 book Women Behind the Camera. “I believe in unionism for working people.”

After KQED disbanded its film unit in 1972, Irola and six others — Gene Corr, Peter Gessner, John Hanson, future ASC colleague Stephen Lighthill, Rob Nilsson and Steve Wax — founded Cine Manifest, a Marxist film collective dedicated to making films reflecting “the diversity of American society.”

Headquartered in a warehouse at Folsom and 11th streets, the group intended to pool resources and inspire revolutionary change through the power of cinema. Its output would include documentaries, PSAs for Amnesty International and two feature films, and for Irola, the politics were not just on the screen. “This was the beginning of the feminist era, but there were not a whole lot of feminists in film at that point,” she told Krasilovsky. “What was important for me in 1972 was to form a collective with six men because men had the power. They still have the power. For the men, it was important that they have at least one woman in the group, and I was the most obvious woman in San Francisco because I had been president of the union.”

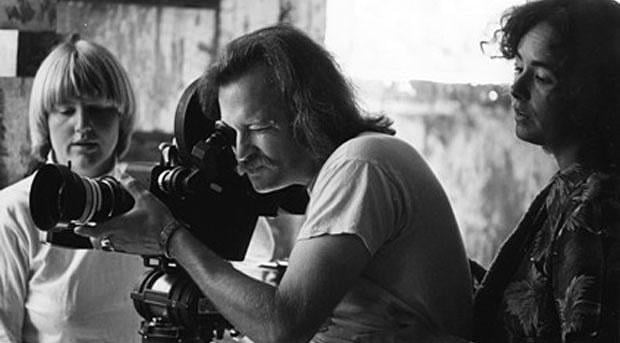

Photographed in black-and-white by Irola and directed by Hanson and Nilsson, Cine Manifest’s Northern Lights (1978) — shot in extreme winter conditions in North Dakota — was a fictionalized account of the populist Nonpartisan League political movement of 1915, which empowered local immigrant farmers against East Coast corporations.

Irola knew she had a lot to prove, but also had encouragement. “Rob and John never criticized me,” she told interviewer Pamela Cohn. “I’d never shot a feature in my life! We didn’t see any footage for weeks. No one treated me like a second-class citizen. When you have that kind of support when you’re that young [29], it’s amazing. And then when we came back and looked at the footage, they treated me like I was God. With that kind of support, you go a million miles; I worked so hard on that film — why wouldn’t I? It was a huge challenge; I was young; it was fun; it was goddamned cold, and I was working with these people who had total confidence in me.”

“There are myriad filters for black-and-white,” she later told American Cinematographer of her approach to the film’s photography, “but because everything was already literally black and white — the sky was heavily overcast all day, [there was] snow on the prairie as far as you could see, and our cast was in tea-stained white or dark brown and black clothes — I chose to use heavy yellow filters. I did tests and was thrilled with their ability to give me wonderful contrast while keeping beautiful flesh tones as people’s backgrounds changed between sky and snow, often in the same shot.”

The film’s debut was an auspicious moment for Cine Manifest: Northern Lights won the Camera d’Or at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival. Regarding Irola’s camerawork, a San Francisco Chronicle critic noted, “As the camera moves from the vast wheat fields to the people, it evokes memories of the great photography studies of sharecroppers and migrant workers by Dorothea Lange in the 1930s.”

Despite its success, the film proved to be the collective’s swan song. “We wanted our films to appeal to large audiences, but we were barely able to support ourselves,” Irola said, describing the 80- and 90-hour work weeks. “There was a personal toll.” The group, shattered by infighting and exhaustion, had actually disbanded by the time Northern Lights had its premiere. “The first year I didn’t bring in a dime, but they supported me financially and emotionally while I was learning my craft,” she remembered wistfully. “I wouldn’t have had much of a career if it hadn’t been for them.”

Irola revisited this formative experience in her documentary Cine Manifest (2006), crafted from more than 40 hours of contemporary interviews intercut with candid group memos, rare photos and clips from the collective’s projects. “It sounds corny, but I learned that you can go home again,” Irola told Fisher. “It was great getting reacquainted and friendly again with people who were an important part of my life. This film was a very emotional experience for everybody in the group.”

The next phase in Irola’s career was precipitated by another move, this time to New York City, where she landed without a job or contacts. It was 1977, and because NABET Local 15 only represented commercial cinematographers and the IATSE camera guild, Local 644, was impossible to join (despite Irola’s experience and credentials), she worked using only the commercial union card. She started shooting news and documentaries for American television networks and international outlets as a freelancer, contributing to 60 Minutes, 20/20, Nova, Odyssey, the BBC, Channel 4 and Canal Plus.

Irola soon met Tom Schiller, a writer for NBC’s Saturday Night Live, then in its third season. They collaborated on eight short films he wrote and directed for the show, among them La Dolce Gilda, starring Gilda Radner, and Don’t Look Back in Anger, starring John Belushi.

Moving further into narrative work, Irola began shooting small, non-union features, including The King of Prussia, Dead-End Kids and King James Version. But when director Lizzie Borden’s 1986 feature Working Girls bowed to exceptional reviews and impressive box office, Local 644 took notice, tried Irola in absentia and fined her $4,000. She fought back, gaining amnesty for herself and others. Yet the union still would not allow her membership, and she was not going to stop shooting, so, in 1989, she moved to Los Angeles.

Returning to television, Irola shot the medical drama Lifestories for NBC. For ABC and NBC, she filmed numerous movies-of-the-week. But the freelance grind was wearing her down, and she was no longer truly enjoying her work.

A bright spot was shooting the feature drama An Ambush of Ghosts (1993), directed by Everett Lewis. Speaking to AC in April ’94, Irola noted how she and Lewis sought an artful approach and found a common visual language inspired by artists such as Edward Hopper, Vermeer and Caravaggio. The character-driven story inspired them to keep the camera moving, following the performances. “We wanted to rivet attention on the screen and create a sense of anticipation,” she explained. “If the viewers look away, even for a few seconds, they might miss something important. This style of shooting wouldn’t be very interesting with ordinary lighting. It’s got to be dimensional to hold their attention. There also has to be a motivation for every light. Everything has to fit: the production design, the words and music, the performances and photography. It’s like putting the pieces of a puzzle together.” For her work on the picture, Irola won the Award for Excellence in Cinematography at the 1993 Sundance Film Festival.

After wrapping An Ambush of Ghosts, Irola became an associate professor at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts, embracing the optimism of education. In 1999, she was appointed head of the cinematography program, designing the curriculum and supervising 26 other cinematographers on the faculty. In 2005, she was named the Conrad L. Hall Chair in Cinematography and Color Timing, a position endowed by Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. In 2018, she retired from USC, where she taught cinematography for 26 years and was head of cinematography for 15.

In 1995, Irola became the third woman invited to join the ASC; she was recommended for membership by Woody Omens, Steven Poster and Robert Primes. Despite this recognition of her talents and character, she noted at the time that “one of my major disappointments is that things are not changing for women [in my profession]. You probably have 2,000 cinematographers in Los Angeles, and out of these, only eight are women. It’s just difficult for women to break in and be taken seriously. The younger generation seems to perpetuate the ancient notion that women can’t handle being in charge of a set.”

Irola frequently spoke at Society events, including “A Day of Inspiration for Women: Finding your Path Within the Industry,” held at the ASC Clubhouse in 2016:

Building confidence in her students, especially women, was a priority for Irola. “Women are great at making films,” she told Cohn. “Visually, women look at things in an intimate way; it’s just instinct. Anybody can set up a light meter. I tell my students, ‘Now, look through the camera. Do you love what you see? Is it attractive? When you look at every corner, are you happy? Are you saying to yourself, Oh, this image is so beautiful!? Don’t be sloppy! That’s not going to get you anywhere.’”

Irola’s honors also included the Women in Film Kodak Vision Award in 1997, the Women’s International Film & Television Showcase Cinematographer Award in 2009 and the Nat Tiffen Award for Excellence in Cinematography Education in 2014.

Describing the cinematographer’s role in the filmmaking process, Irola told Krasilovsky, “Next to the director, [the cinematographer is] the most powerful person on the set. You can be creative, and you can be managerial and spirited. There’s something incredibly sexy when you put your eye up against an eyepiece and you direct what is basically going to come into that image. You control the lighting; you control the frame, how much air there is between the subject’s head and the top of the frame, where it stops on the left, where it stops on the right, what the colors are …. Ultimately, film is a visual medium. It isn’t about the camera and technology. It’s about vision, an artistic vision.”

The remembrance found here was penned by colleague, friend and ASC member Joan Churchill for the International Documentary Association.