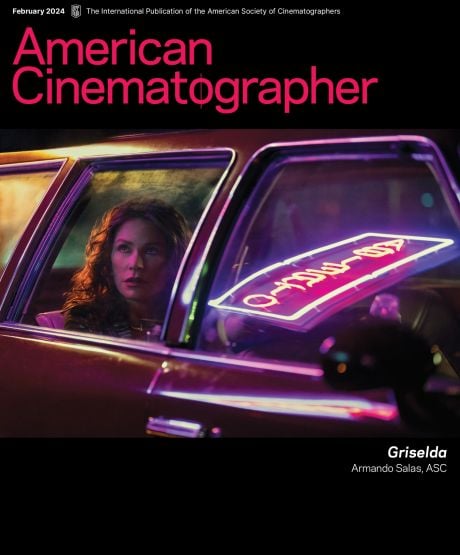

Visual Analysis: Contact

Don Burgess, ASC reaches for the cosmos in this ambitious science-fiction drama.

Unit photography by François Duhamel

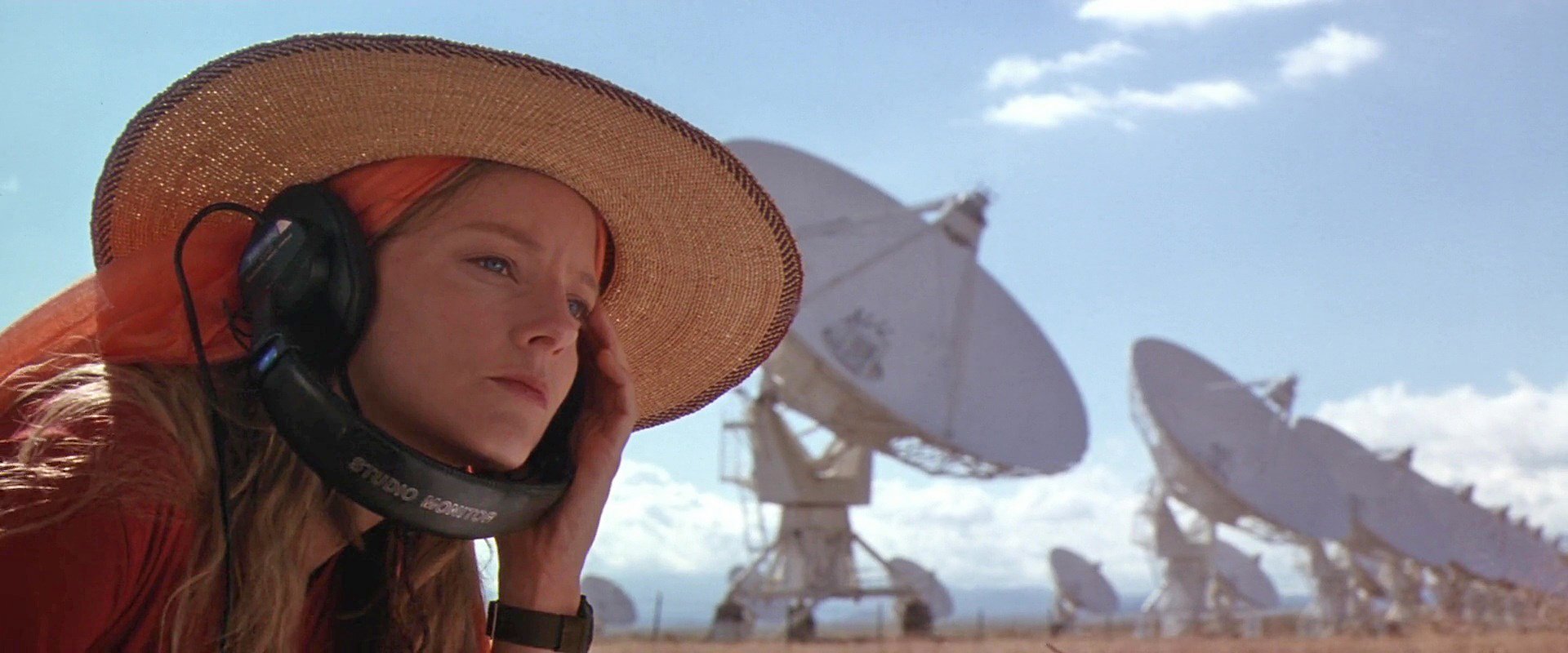

Based on the 1985 novel by Carl Sagan, Contact tells the story of Eleanor Arroway (Jodie Foster), a scientist with the SETI Institute who discovers evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence. Though handicapped by politics and personal beliefs, Arroway is dogged and relentless in her pursuit of the truth — who sent the message, and why? — aided by such unlikely allies as mysterious industrialist S.R. Hadden (John Hurt) and charismatic religious philosopher Palmer Joss (Matthew McConaughey).

Released in 1997, Contact marked the second feature collaboration of cinematographer Don Burgess, ASC and director Robert Zemeckis, following Forrest Gump (1994). (The count now stands at 15; their latest, Pinocchio, is due in 2022.) Whereas Forrest Gump is a gauzy, Norman Rockwell-esque slice of Americana, Contact is a sharp and polished science-fiction odyssey captured in the 65mm, VistaVision, and 35mm anamorphic camera formats.

“Wide-angle lenses are more storytelling lenses — it’s a focal length that keeps the subject and the environment in focus for the most part, and it keeps your subject really connected to the environment and the other actors in the scene.”

— Don Burgess, ASC

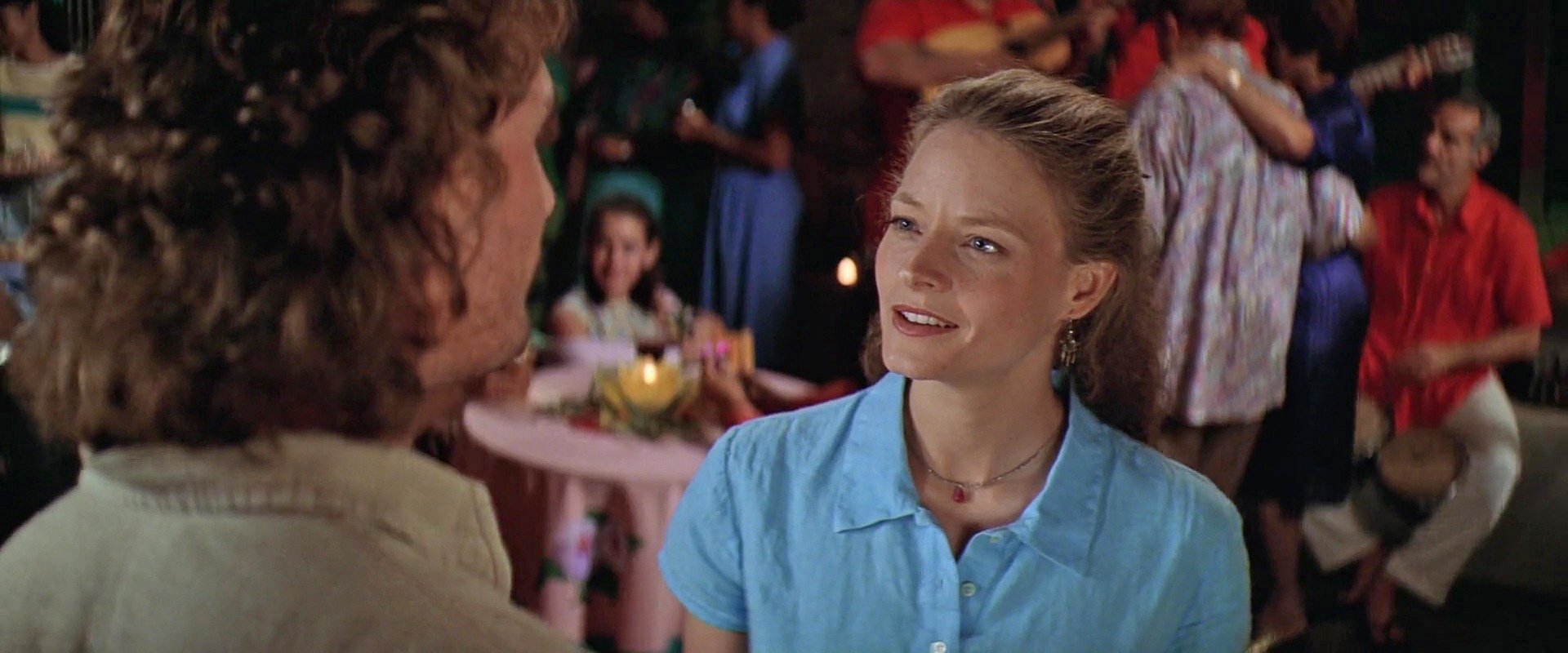

An understated but effective example of this approach can be found in an early party scene where Arroway breaks into a conversation between senior science advisor Dr. David Drummlin (Tom Skerritt) and another group of scientists.

Zemeckis’s directorial voice is formalistic without resorting to an overly simplistic approach. In fact, the opposite is true, with each widescreen frame meticulously composed and each camera move carefully blocked, in this case, almost entirely from one angle: the wide shot that opens the scene at first accommodates seven characters, then, as it trucks left and pans right, the focus shifts to Arroway and Drummlin's interaction.

Palmer Joss enters the scene in a frame-left over-the-shoulder, shifting the focus of the conversation.

The scene's only clean single, and also Arroway's POV. Not only is Joss an outsider — he's there alone, a man of the cloth among scientists — his presence calls for special attention.

Back to the master, Drummlin and the other scientists exit frame left. Joss crosses to Arroway and the camera dollies in over her shoulder.

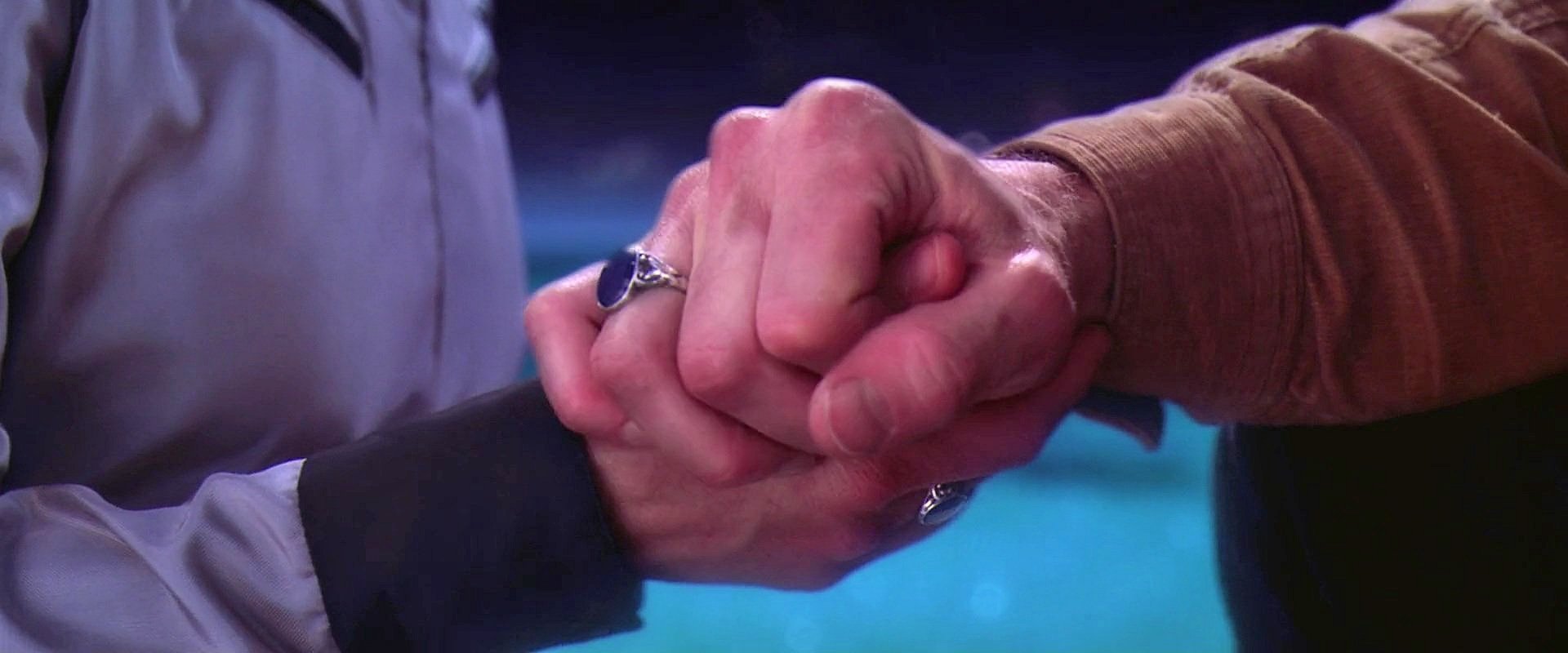

The scene now consists of two over-the-shoulder singles. Joss and Arroway's screen direction is consistent throughout.

“Contact is definitely told from Ellie’s point of view, so all decisions about where the camera should be were structured from where she was, what she was doing, and how she saw the situation.”

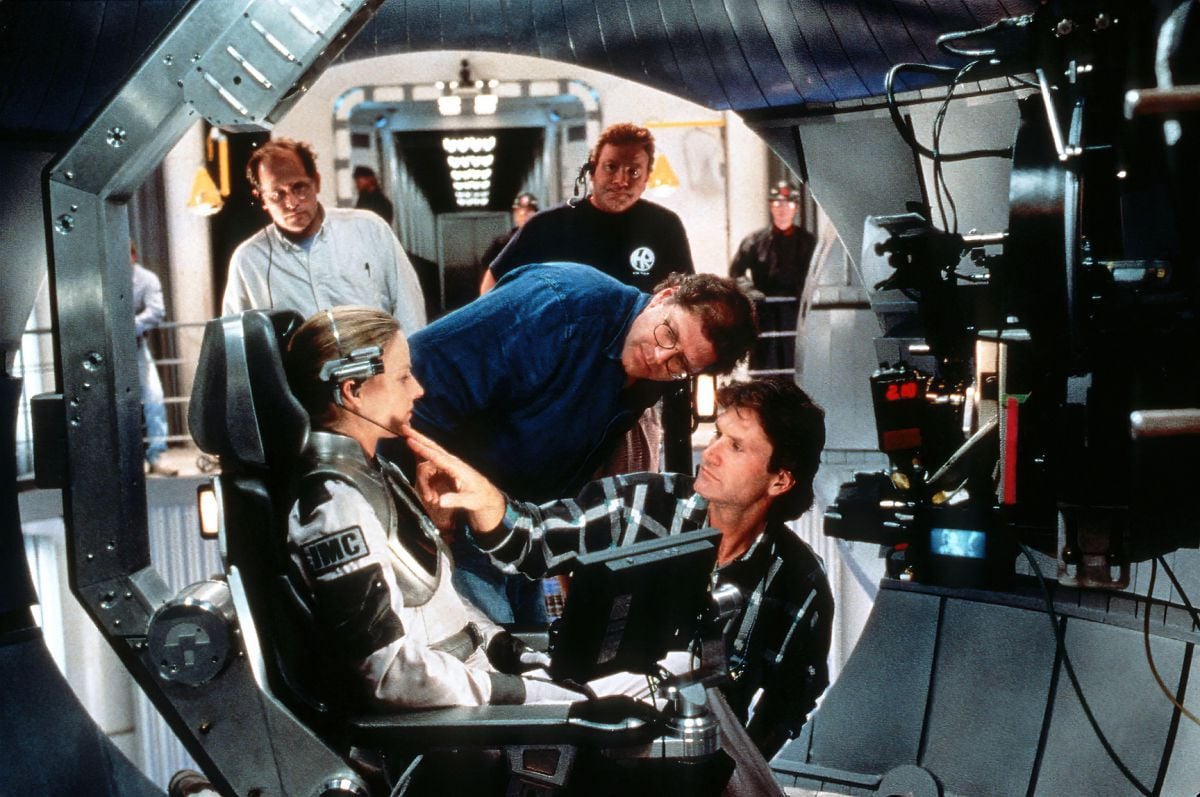

The alien intelligence transmits a set of instructions for building a massive transportation device, and after rocketing through what appears to be a transit system of interdimensional wormholes, Arroway is deposited gently on the shores of a cosmic ocean — a psychedelic interpretation of a drawing of Pensacola, Florida she made when she was a child. An alien simulacrum of her deceased father (David Morse) appears, introducing itself as the source of the message from space.

“You’re an interesting species... You’re capable of such beautiful dreams and such horrible nightmares,” the alien tells her.

Burgess and Zemeckis illustrate this dichotomy of dreams and nightmares throughout the film, in repeated close-ups on the principle physical expression of human potential: hands.

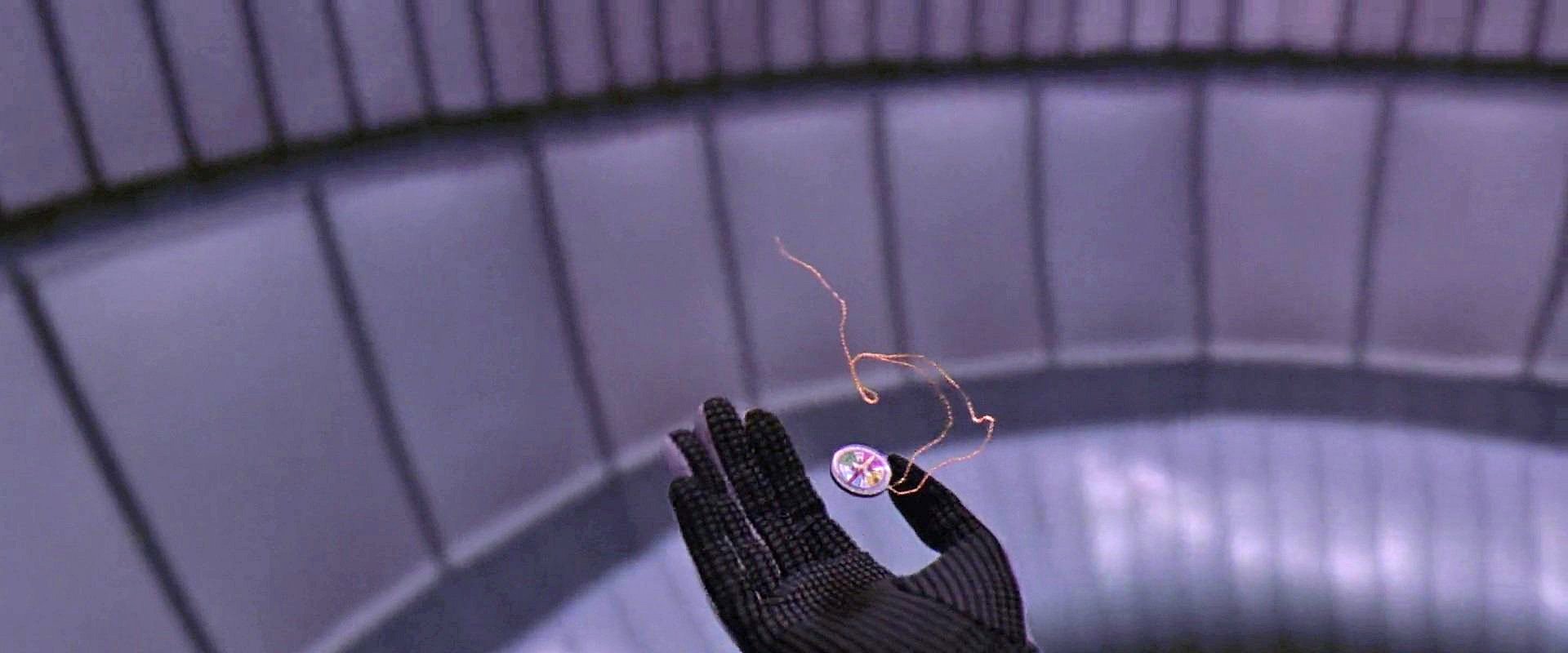

A toy compass is passed back and forth between Joss and Arroway as the story unfolds. "You'd better keep this, it might save your life someday," she tells him.

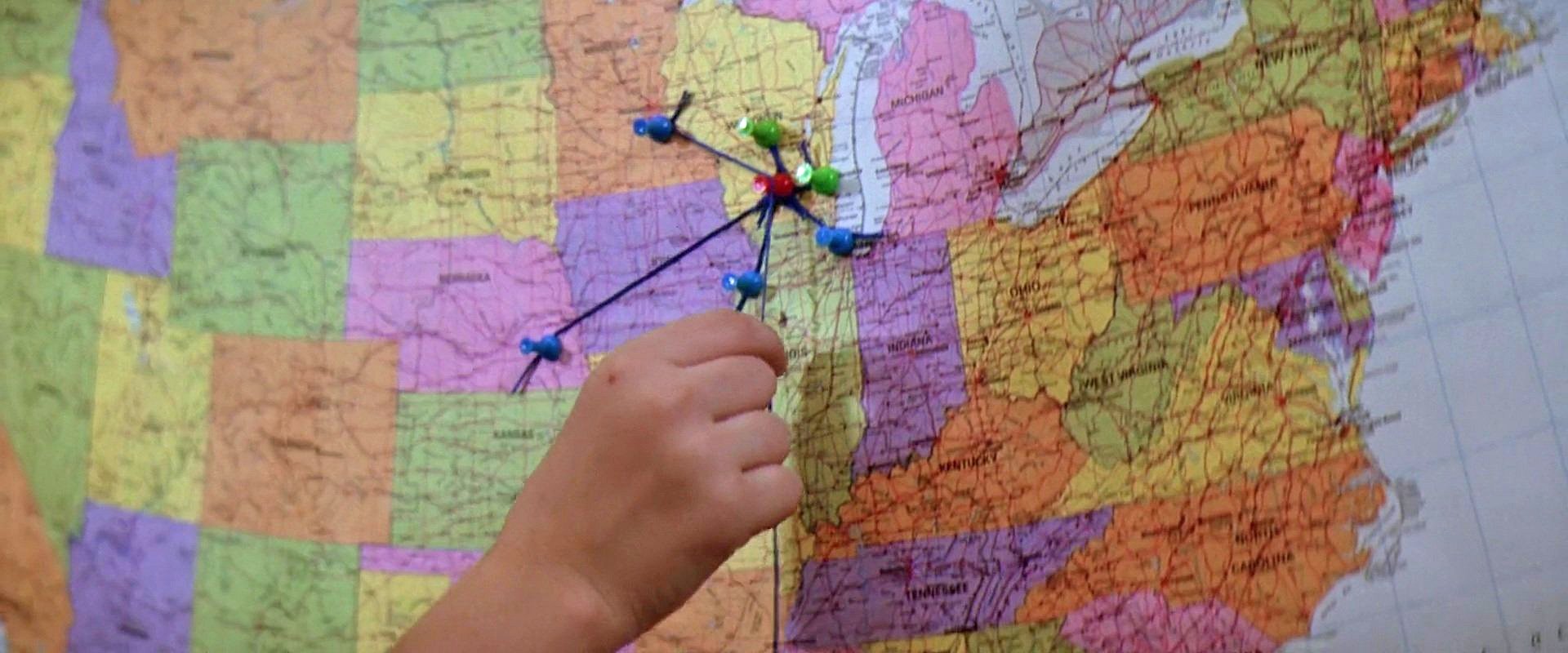

Hands indicating contact over distances.

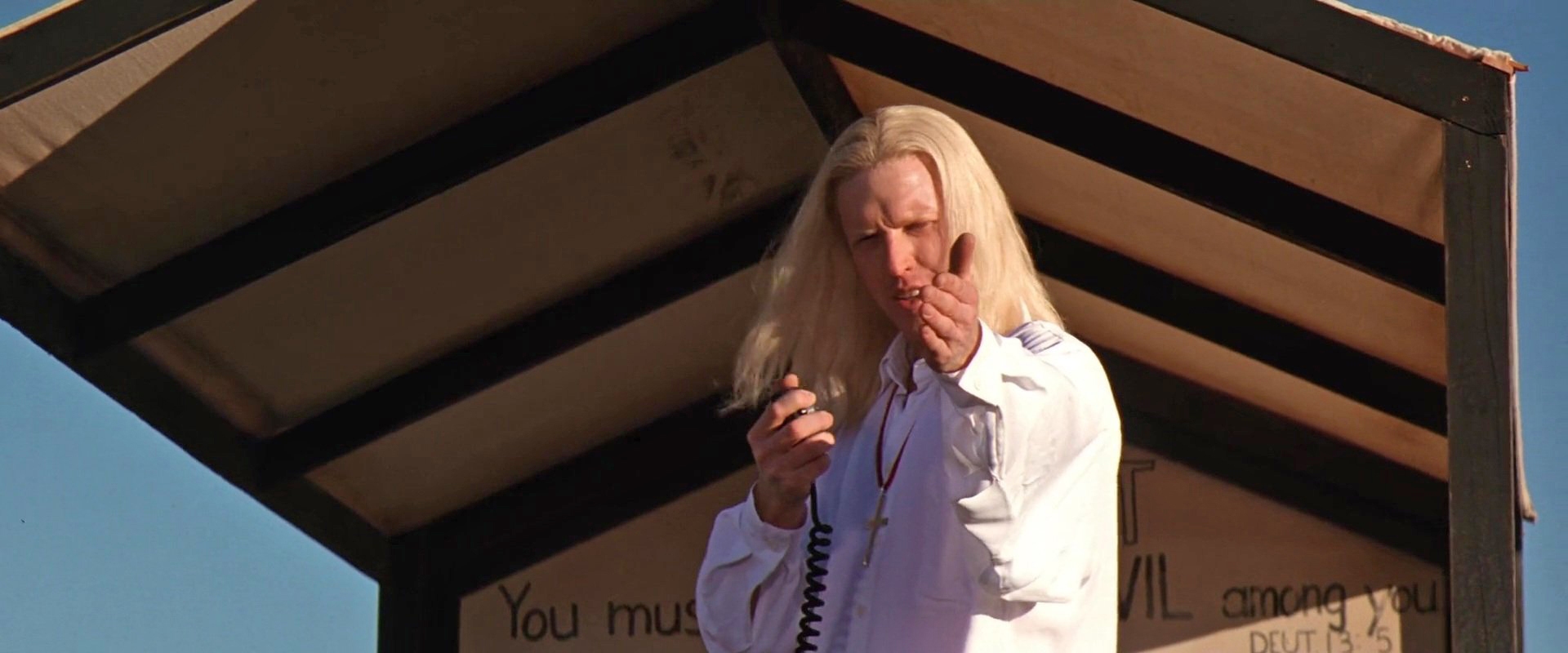

The religious zealot Joseph (Jake Busey) accuses the scientists of heresy, then later attacks them with an explosive device.

Hands holding constellations of stars.

“You feel so lost, so cut off, so alone. Only, you’re not. In all our searching, the only thing we've found that makes the emptiness bearable is each other.”

"The thing with the hands wasn't intentional," says Burgess in a contemporaneous interview. "It comes from Robert's filmmaking, each scene evolves through camera movement rather than editing." In Contact, there are no cutaways — every shot goes deeper into or directly relates to a point of action in the master or corresponding single. This linear visual approach works in service to the story by underlining the significance of contact between people as well as the universe, through sight, sound, belief, and touch.

“So much work went into designing every shot,” Burgess remarks, 24 years later. “Contact is still the most challenging picture I’ve ever worked on.”

Contact (1997)

Dir. Robert Zemeckis

DoP: Don Burgess, ASC

Production Designer: Ed Verraux

Visual Effects Supervisor: Stephen Rosenbaum (Sony Pictures Imageworks)

2.35:1

Panavision Platinum, System 65, Beaumonte VistaVision, Super 8mm, Hi-8, Betacam

Panavision C-Series anamorphic primes

Kodak Vision 200T 5293 (daytime interiors; bluescreen); Vision 320T 5277 (White House daytime interiors); Vision 500T 5279 (nighttime exteriors); Vision 100T 5248 (daytime exteriors)