Up in the Air with Helicopter Film Services

When it comes to getting just the right shot from aloft — or on the ground — artistry, experience, technical savvy and safety all come into play.

When it comes to getting just the right shot from aloft — or on the ground — artistry, experience, technical savvy and safety all come into play.

“Generally, helicopters are designed to point forward,” says pilot Giles Dumper with some understatement. “Particularly if you’re going at any decent speed, you want to be flying them in what we call ‘trim,’ or forward, as streamlined as possible. Flying them sideways isn’t really how they’re designed to operate.” However, as a frequent pilot for London-based Helicopter Film Services (HFS), Dumper is very used to flying helicopters sideways.

The genesis of HFS is found in the early experiences of founder Jeremy Braben, whose experience in the air dates back to 1979. “I was in news and current affairs at the Nine Network in Australia. The company had a ’copter and I used to do my fair share of work with it. The aerial side wasn’t my main job but I’d always had a passion for flying. It stems from a desire, when I was a child, to be a pilot. That was my ‘job’ whenever I was asked.”

Years later, Braben would find success as a cameraman, moving on to direct photography on drama and commercial shoots, as well as music videos. “It was in the early ’90s that... I basically came home one night and announced that I’d had enough — I couldn’t deal with those people any more. I announced that I was getting out of it and I was going to go and fly helicopters for a living. My wife said, ‘No you don’t; I don’t want to go to Australia. Can’t you combine your passions?’”

Initially, equipment was primitive, Braben continues, “Back in the day, it was 16mm film. When I joined, it was just switching over to video, BVU-series U-matic, Sony cameras and these big tape decks that this poor fellow used to lug around.” At that time, shooting was mostly handheld, progressing eventually to basic internal mounts. By 1998, however, Braben would become involved with Wescam, whose gyro-stabilized helicopter mounts initially had to be leased rather than owned and were rare and expensive. “There were very few of them, so the work was global. The system would go from Thailand to Australia to the UK to wherever the work was required.”

Over time, this would change, with smaller, lighter equipment and a proliferation of it that has diffused the available work. HFS’s success, Braben feels, is because “I have very good people with me — the company wouldn’t be where it is today without the operators, the technicians and the pilots we’ve worked with — and we do good work.” Braben has preferred to specialize in feature films and commercial work. “There are other companies that are extremely good at news and live broadcast; that's not our expertise. That explains why we’re wall-to-wall movies and an equal number of commercials. The equipment we have is out of reach of television.”

AC caught up with Braben on the set, or, rather, the airfield, of a shoot designed to showcase the company’s considerable capability in both aerial and other vehicular camera mounts. The facility at Bovingdon, northwest of London, went out of military use in the late 1960s. It has since been used on features from Battle of Britain (1969) all the way up to recent productions including Rogue One and Fury, and part of one runway remains in use for general aviation. HFS, based at nearby Denham Aerodrome, chose Bovingdon as an ideal place to showcase their vehicles with ample room to operate both a helicopter and drone.

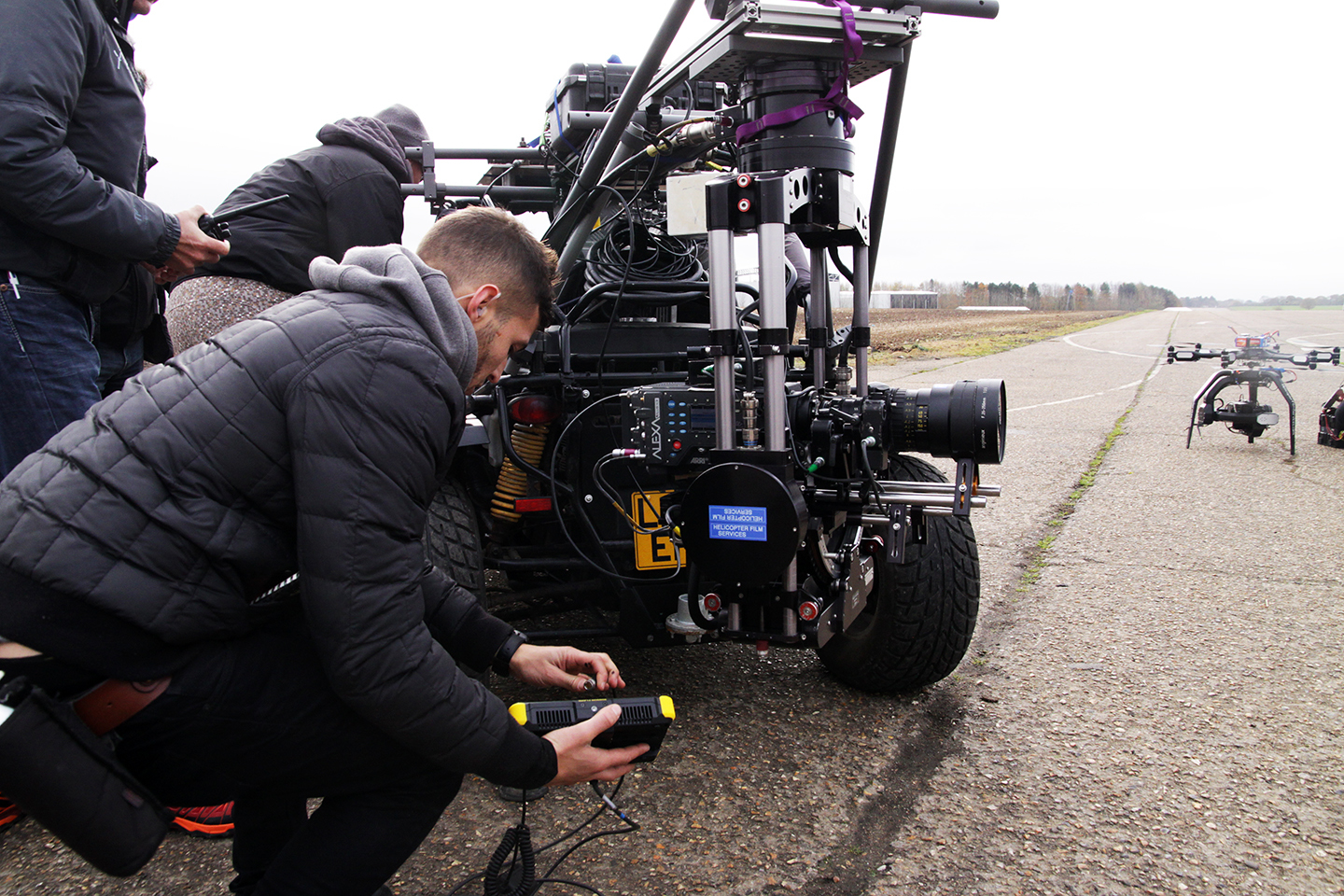

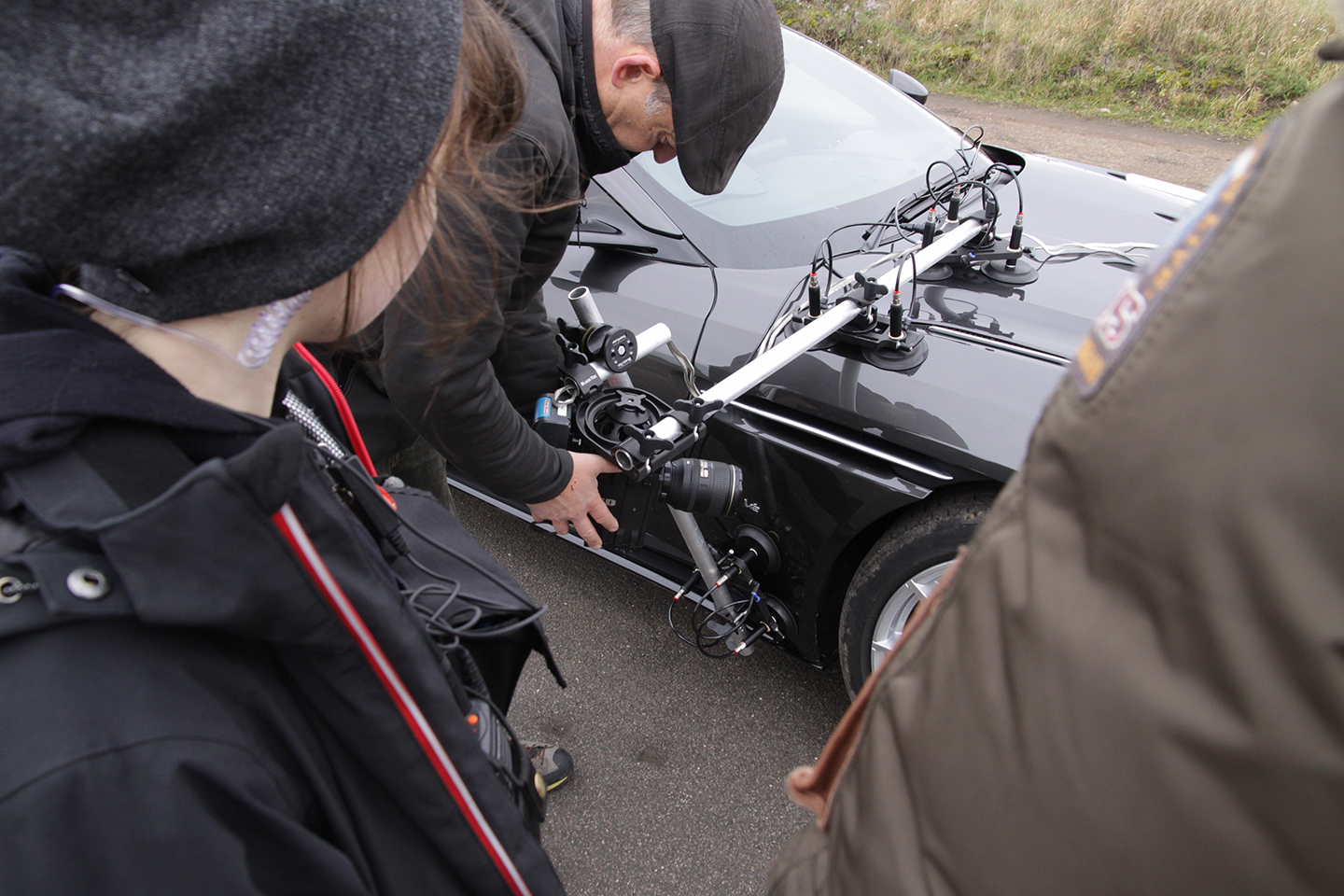

“The idea for that came through from one of our aerial DPs,” Braben explains. “Jim Swanson said, ‘You know, you’ve got all of these toys, nobody really knows what we’ve got, let’s get them all out and see if we can conjure up a little commercial that develops in an interesting way that actually shows off all of our equipment and capabilities.’” Given the intended results, the shoot required a lot of cameras, including the Red Weapon on a Black-Tek Tower mount, stabilized with the Shotover U1 and all riding on HFS's Aston Martin Cygnet tracking vehicle. Another Weapon was hard-mounted on the hero Aston Martin, with a further camera on HFS's Mitsubishi Evo tracking vehicle.

A full-size Alexa was used on 500cc four-wheel-drive vehicle — the “Quadzilla” — with an Angenieux Optimo 25-250mm zoom, stabilized on a Nettmann Stab-C head. An Alexa Mini was mounted on an IA3 Aerigon drone, flown by Alan Perrin, and equipped with a 27mm Arri Ultra Prime lens. No less than six more Alexa Minis were mounted on the company’s Typhon array:

This device was created by HFS for visual effects applications, riding the Airbus AS355 helicopter, flown by Dumper, on a Shotover K1 helicopter mount that provides both stabilization and pan-and-tilt control. The six Alexa Minis are invariably recorded in open-gate raw to create high-resolution, broad-coverage plates for VFX, and the system was first deployed on Paddington 2.

As a veteran pilot, Dumper is, naturally, cautious about the safety aspects of putting all this equipment so close together. “I don't think there’s been many filming setups in which a drone has flown close to a helicopter. I think we got about as close as we could — certainly 30 meters or less. I don’t think I’d have done it if it hadn't been an HFS shoot. If it had been ‘John Smith’ the drone bloke... eh. You've got to be quite clear who’s flying.” Practically, too, the drone has only a limited ability to resist the huge amount of air that is moved around by a full-size helicopter, a problem solved with careful choreography.

“Because of the positioning we had against the drone, we were mainly behind it,” Dumper reports. “There was one point where we did a breakaway at the end of the run and as we pulled away that fired off a load of our wash toward the vehicles. But in general it didn’t seem to cause any upset at all.” There is, as we might expect, a certain degree of good-humoured rivalry between drone and helicopter people, although both are keen to emphasize how the two complement one another. “At the moment, there’s a fair amount of overlap. I think that overlap will reduce and people identify exactly how drones should be used.”

The camera technique required for helicopter photography is split, Dumper feels “into two main camps. The first is... typically a fixed site — a building — then you're doing a fly backwards or a reveal, a sweep around it. You have a bit of distance; you're not quite so concerned about distance to the ground but you're doing a lot of sideways and backwards. You're maintaining frame to the target building and the vehicle is maneuvering in the correct manner without causing it any issues. Then there’s speed-related stuff, which in many ways is more fun and is generally easier because you’re generally going forwards, trying to keep position.”

Naturally, the relationship between the pilot and onboard camera operator is crucial. “A pilot who can’t or won’t maneuver the machine to enable a desired shot, within the limitations of the airframe, isn't of any use,” Dumper attests. “Neither is an operator who demands too much or ignores those limitations and the pilot with it. Thankfully, HFS has some excellent people who know both how to make a shot, but also to make it work with their pilot.” Storyboards or other planning can also present impossible shots, and the pilot-operator team must then gently introduce the director to more achievable alternatives.

At the time of this writing, HFS’s promo was still in postproduction, which is particularly important given the difficulty of lighting such a huge shoot. “We do have to go with what we get,” says Braben. “The Alexas are high-dynamic range, they can handle that difference in exposure, the flat tones, very well. Then, I guess we're into the grade. We were very top-heavy with DPs on that shoot — we all have slightly different opinions, none too wild and we all came to the conclusion that it's all down to the grade on this one.”

Pondering the sheer scale of what was being brought together in terms of both crew and equipment, “I was touched,” Braben says. “A lot of people gave their services to us and we have a long standing relationship. It’s one of those things that makes me immensely proud is that it’s not me coming up with a lot of these ideas. It’s the people who work with us.”