The Game Changers: Plant-Based Power

Cinematographers John Hunter Nolan and John Behrens travel the globe for director Louie Psihoyos’ documentary about the benefits derived from a plant-based diet.

Cinematographers John Hunter Nolan and John Behrens travel the globe for director Louie Psihoyos’ documentary about the benefits derived from a plant-based diet.

Frame grabs courtesy of Game Changers Film LLC. Additional photos courtesy of John Hunter Nolan, John Behrens, Luis Escobar and Gina Papabeis.

The documentary The Game Changers premiered at this year's Sundance Film Festival and, at the time of this writing, is about to screen at the Hot Docs Canadian Documentary Festival ahead of its release in the fall. Directed by Louis Psihoyos, the movie tracks combatives expert and former UFC welterweight champion James Wilks as he recovers from injuries he sustained to both knees while sparring. To speed his recovery, he pores over peer-reviewed science and soon finds a study presenting evidence that Rome’s gladiators were fueled by a plant-based diet. The ultimate fighters of long ago were vegans.

The realization launches Wilks on a journey that introduces him to a wide range of doctors and scientists, as well high-performance athletes whose successes have been fueled by their vegan diets: ultrarunner Scott Jurek, who will set out to break the Appalachian Trail speed record; professional strongman Patrik Baboumian, who will attempt to set a new world record for the yoke-walk; U.S. national cycling champion Dotsie Bausch; bodybuilders Nimai Delgado and Mischa Janiec; and many more.

For the documentary, Psihoyos teamed with cinematographers John Hunter Nolan and John Behrens, both of whom had also worked on the director’s previous documentary, Racing Extinction. AC caught up with the cinematographers via conference call, with Behrens dialing in from his home in Oakland, Calif., and Nolan connecting from Brooklyn, N.Y.

An extended Q&A will appear in the magazine's June issue, but to coincide with The Game Changers' Hot Docs screenings, we here present additional content from the conversation.

American Cinematographer: Would you have much downtime between the different subjects you were shooting?

John Hunter Nolan: Over the course of the two and a half years we spent in production, there were times when we were on for a month, off for a month, on for a week, and then off for two or three weeks, something like that. Because it was so subject-focused, there was a lot of, ‘We know this event is going to happen in four months, so book this.’ And then there was also a lot of, ‘We just found out about this amazing person who’s doing this in three days — can you get a team together?’ So it was really varied in terms of lead time and the length of the shoots. But the producers did a fantastic job of building all these things together as much as possible in order to allow us to get into a flow and really push forward. Sometimes you can have too much downtime, and then you’ve got to actively remind yourself, ‘What is my visual language? How have I been covering this?’

John Behrens: I create a sort of tech-spec white paper for every documentary that I work on, with camera settings and lensing choices, and if there are very specific interviews, it will have diagrams of the lighting setups. And then of course we have all the carnets and camera packages that we’ve used previously. We’re often working on several documentaries at one time, so if you’re off the project for very long, you really have to reacquaint yourself and make sure that everything is back in spec.

Were there instances when you had to go back and revisit a subject more than once?

Behrens: Especially on our Europe trips, we tried as much as possible to bring every tool with us so we could shoot it out. But realistically on a documentary, with real characters living real lives, events happen for them where you have to go back to shoot the competition, as in the case of Patrik Baboumian, our German strongman. Our German second-unit director of photography, Max Preiss, shot Patrik’s competition in Berlin — and then there was another competition in Canada. And I spent three weeks in England with James [Wilks], and then, Hunter, did you go two more times?

Nolan: I went back to his hometown once, but we did a couple other stops in Europe on that same trip. It was a whirlwind. We also did Zimbabwe [for the sequence featuring Damien Mander, who heads the International Anti-Poaching Foundation]. We tried to batch all these things together as much as possible, which was definitely a feat for our producers. I think the standard shoot was a week or two, out in the field with four different subjects. If it was an information-based subject, then that was typically a single trip. But a lot of these athletes we were seeing once, twice, sometimes up to three times depending on their specific athletic event.

Behrens: Every character-based documentary benefits a great deal from real-life things that are going on for the person. Scott Jurek’s arc was a wonderful one because it’s this triumphant accomplishment spanning [approximately] 2,200 miles. That’s a hell of a story. If at all possible, you have to follow that arc with the character.

Nolan: We were living with that suspense, too. While out on the Appalachian Trail, three days out from the finish, I was thinking, ‘This guy’s not going to break the record. This is not going to happen.’ That’s the beauty of documentary film, the fact that we’re not writing this. We’re watching this unfold. We’re witnesses to this, and we’re doing our best to be able to share it in a way that’s digestible, entertaining and true.

Behrens: I like to say that documentary is an evolutionary storytelling process — and it evolves whether you like it or not. Usually the evolution is a positive one because it’s true life and it moves the story along. Even when unfortunate things happen, they still are the stuff of life.

I feel like every documentary that I’ve worked on has been a master’s degree in whatever subject [the movie covers], because as a cinematographer you spend usually a minimum of two years on a project, and you’re intimately involved with the subject matter, the story, the characters, all the information. You have to become an expert, and you have to live completely in that space to be able to tell the story. To be able to catch Scott at his next pass, you couldn’t just casually catch him running by; you had to be embedded with Scott Jurek.

Nolan: Same thing down in Zimbabwe when we were out shooting night vision on an anti-poaching mission. There’s no bail button when you’re in the bush in Zimbabwe.

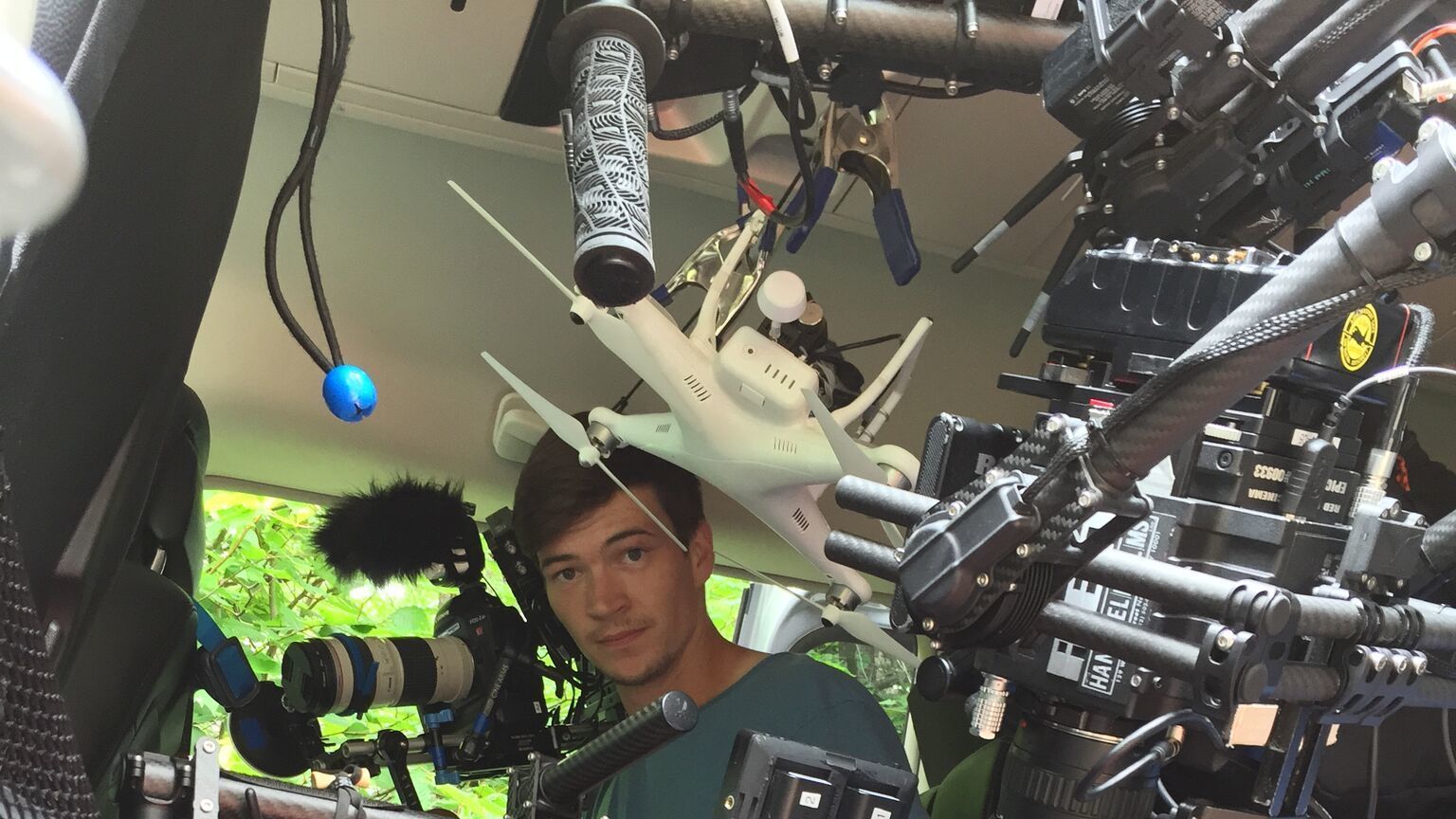

Behrens: Doing this kind of work, there’s no evac. You’re there. And so you can’t f--- up. You have to not get hurt, and you have to make sure that what you do does not hurt anyone else. That’s a golden rule of documentary: You can’t hurt your subject or the environment that you’re documenting. You’re in a unique position to be in a place with a camera, and when you’re doing things like flying drones and Movis and cable cams, you’re doing stuff that’s pretty risky for the crew and for the subjects. You can’t hurt anybody.

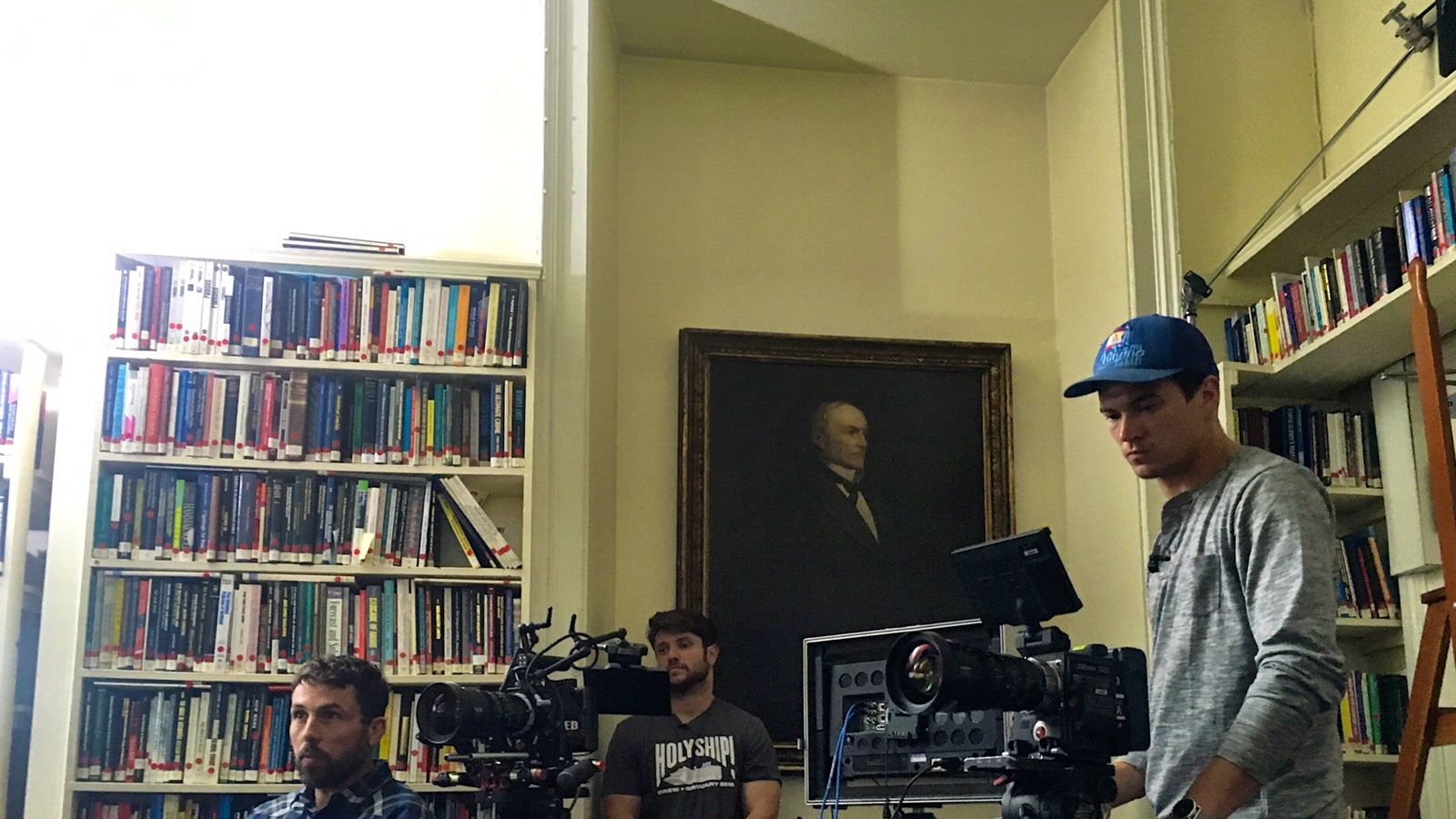

Were you able to work with the same crew throughout production for The Game Changers, or did you have to find different people every time things started up again?

Nolan: I definitely had my priority list in terms of people who are most familiar with the packages that I was using and really game for an adventure. I can’t just take someone who’s technically versed but is not interested in some of these scenarios where we find ourselves. The number one thing is good energy. You’ve got to be good at what you do, but you also have to bring something bright to the shoot.

Different people brought different things. My team from the Appalachian Trail helped me redefine what’s possible with a camera; my friend Jared Levy helped me solve so many challenges with a critical eye; and my operator, AC, and all-around collaborator Ali Cengiz was instrumental in keeping the ship upright and figuring out how any given idea was technically achievable. I was so lucky to be surrounded by a team of this caliber.

Behrens: My right-hand man was Ethan Johnson. He was my first AC, and he was essential because of the wide variety of cameras. He actually has worked with Louie longer than I have; he worked on almost all of Racing Extinction. Ethan is an absolute genius. He knows every camera under the sun, is a trained Phantom tech, and is extremely organized. With the amount of cameras that we had, it took two very A-type people to manage the camera department. He and I were both to our edges, and then Ethan would be up late every night wrangling all the media that would pile up throughout the day, because there was really no chance for us to wrangle in the daytime. So I worked with Ethan as much as possible.

For some of the shoots in the U.S., I brought in Andrew Eckmann to both AC and operate a second camera; Drew has a great eye and had worked on quite a bit of Racing Extinction as well, so he really knew Louie’s style. I also had a great AC in L.A., Robert Royds, who was great at handling all the cameras we had to work with. Lucy Sheils and Gabe Monts were our sound recordists and really helped the production along. And then we hired gaffers almost everywhere we went.

Nolan: As anyone who works in this business knows, there are so many instrumental components to this machine. By the time we get our moment to shine, so many people have put in so much work. And after we have our moment to shine, there are still so many people who have so much work to do. We don’t have the opportunity to do our job well without the entire machine running at full steam.

The same way that a lot of the athletes and their supporters were pushing each other, it really felt like that for us as a team of filmmakers. There were often a lot of midnight wraps and 5 a.m. calls to get what we needed, and different people would step up at different times to be the source of energy. Especially Louie, he knows how to go and go and go, and how to get the people with him engaged in a way that they couldn’t be more excited. At a certain point it feels like you’re on a mission more than shooting a film.

Behrens: Yeah, I second that. I’m extremely thankful to our field producers Gina Papabeis and Brook Holston, who were instrumental to keeping us on the road safe and with everything we needed. We were stoked to have them and the whole team. I feel very lucky to have worked on this film and to have had this experience.

Read more with Nolan and Behrens in the June issue of American Cinematographer.

TECHNICAL SPECS

1.78:1

Digital Capture

Sony CineAlta PMW-F5, XDCam PXW-FS7, a7S II; Red Epic Dragon 6K, Epic-W Helium 8K; Canon EOS-1D C; Vision Research Phantom Flex4K

Arri/Zeiss Master Prime, Ultra Prime; Zeiss Super Speed Mk II; Fujifilm/Fujinon Premier PL Cabrio; Canon Cinema, L series; Leica R; Zeiss ZF