Stereoscopic Motion Pictures - Part 1

Periodically, some powerful new innovation develops to change the course and fortune of Hollywood motion pictures. Will stereo become the next major change in entertainment films?

By J.A. Norling

Never before has the subject of stereoscopic motion pictures received such serious attention as is presently in evidence, both here and abroad. Stereo movies are freely predicted as the next big development in motion picture entertainment. The major problem yet to be hurdled seems to be how to simplify their presentation in existing theatres and in such a manner as to gain general public acceptance. Beginning on this page is the first of a two-part comprehensive summary of the present status of stereo movies by a man who has pioneered in their development and who is considered an outstanding authority on the art — Mr. J. A. Norling, president of Loucks & Norling Studios, Inc., New York City. The study appeared in a recent issue of International Projectionist, and is reprinted here by permission. Elsewhere in this issue will be found an article dealing with a new application of stereo to 16mm home movies. — Editor

That the motion picture industry could use something to combat television’s capture of more and more of the theatre audience is undeniable. Stereo movies might well induce people to return to their former favorite amusement. But the return is likely to come about in the mass only if the film theatre gives them something they can’t get on a 17-inch TV tube, namely the ultimate in photographic realism, the stereoscopic movie in full color, with all dramatic possibilities that are only waiting to be appreciated.

The enthusiastic public reception given some earlier stereo movies and the dollar profits from these movies are a matter of record. Newer, better stereo techniques are now available, and the reason for introducing them was never more pressing. Will the motion picture industry take action?

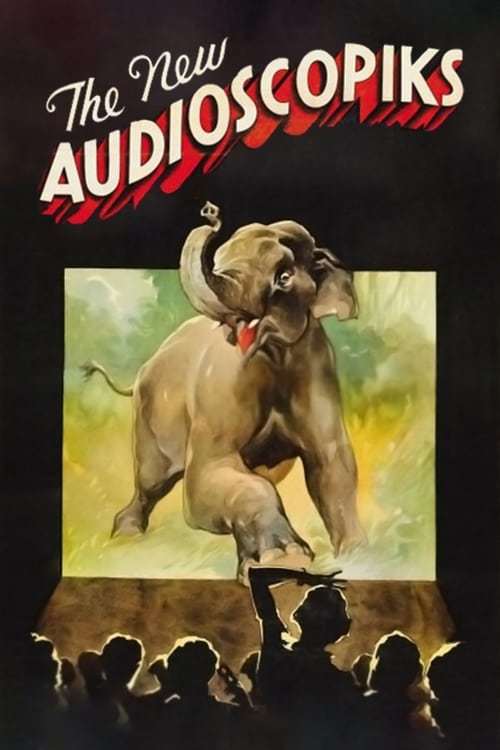

One of the early and noteworthy theatrical exhibitions of stereoscopic motion pictures occurred in 1924, when J.F. Leventhal produced a few “shorts” utilizing the anaglyph process. There followed an 11-year lull in the use of stereoscopic films. Then in 1935, Loucks & Norling Studios and Mr. Leventhal jointly produced a series of short films again employing the anaglyph principle, this time in talking-picture form. These films, which were called Audioscopiks, were released by Loews, Inc. and proved to be some of the most successful short subjects ever issued, winning not only domestic acceptance but an unprecedented play in the foreign field, notably in France, Spain and Great Britain.

That their success should have indicated further pursuit of the anaglyph process seems logical. But the producers had, from the beginning, realized the inherent limitations of the process and concluded that films exhibited by that process would only be adequate as novelties and would never be tolerated for full-length feature releases.

This conclusion was arrived at by a recognition of the visual “insult” resulting from the projection of one color to one eye and its complementary to the other. This sort of delivery of images, one color to one eye, another to its mate, produces “retinal rivalry” and brings on physiological disturbances that may induce nausea in some observers if they look at the anaglyph longer than a few minutes.

Since this process — the anaglyph — has played an important role in the advance of the stereoscopic art, it would be well to describe it here briefly. Its invention is credited to Louis Arthur Ducos du Hauron, who applied it in 1895, although there is some evidence that its possibilities had been explored many years before that.

In one form, the anaglyph images are on two separate films. One member of the stereoscopic pair is projected through a filter of one color, the other through a filter having a color complementary to that of the first. In another form, the one that was used for Audioscopiks, the anaglyph images are printed in complementary colors directly on film and projected in a standard projector without filters.

The projected images are viewed with spectacles having windows of the same colors as the colors on the screen. Red-orange for the right eye filter and blue-green for the left are often used. The right-eye red-orange filter in the viewing spectacle renders the blue-green right-eye image in monochrome and the left-eye blue-green filter renders the red-orange left-eye image also in monochrome.

Since dyes and pigments hardly ever are capable of transmitting only the color they are supposed to transmit, there is rarely a complete cutting of one color: some of it always comes through so that part of the blue-green image which is supposed to be blocked by the blue-green spectacle filter leaks through, producing a “ghost” image. So, in reality, the one eye sees a part of the image intended for the other; the “part, of course, being defined as a very dim, but still discernible remnant of the whole “other-eye” image.

Good picture quality has never characterized the colored anaglyph. This and other shortcomings make it eligible for discard as a practical system for motion picture features.

Since the introduction of Polaroid light-polarizing filters, it is possible and practical to substitute these for the red and green filters of the original anaglyph process. Strictly speaking, the polarized light method may be defined as another form of the anaglyph. Actually, Polaroid Stereoscopy would be a good name for it. It was Dr. Edwin H. Land, head of Polaroid Corp., and his invention of the first practical and efficient synthetic polarizer which hastened the increasingly widespread use of the present satisfactory methods of stereoscopic projection.

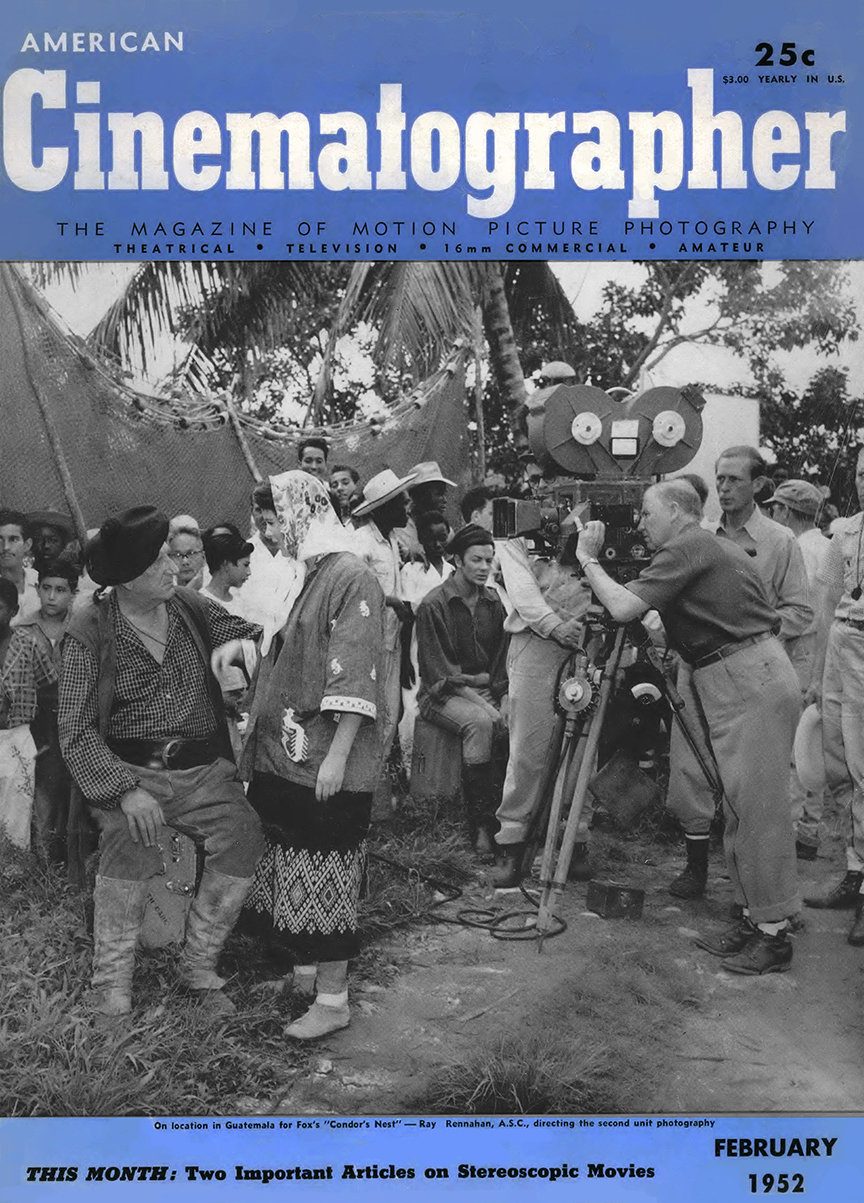

The first large-scale public exhibition of a stereoscopic motion picture with excellent picture quality took place in 1939 at the New York World’s Fair. That year a black-and-white film was shown. The following year a similar subject was exhibited in Technicolor. More than five million people saw these films,* and they’re still talking about them. Some of the production and exhibition problems posed by there pictures are interesting to consider. [*Produced by the writer.]

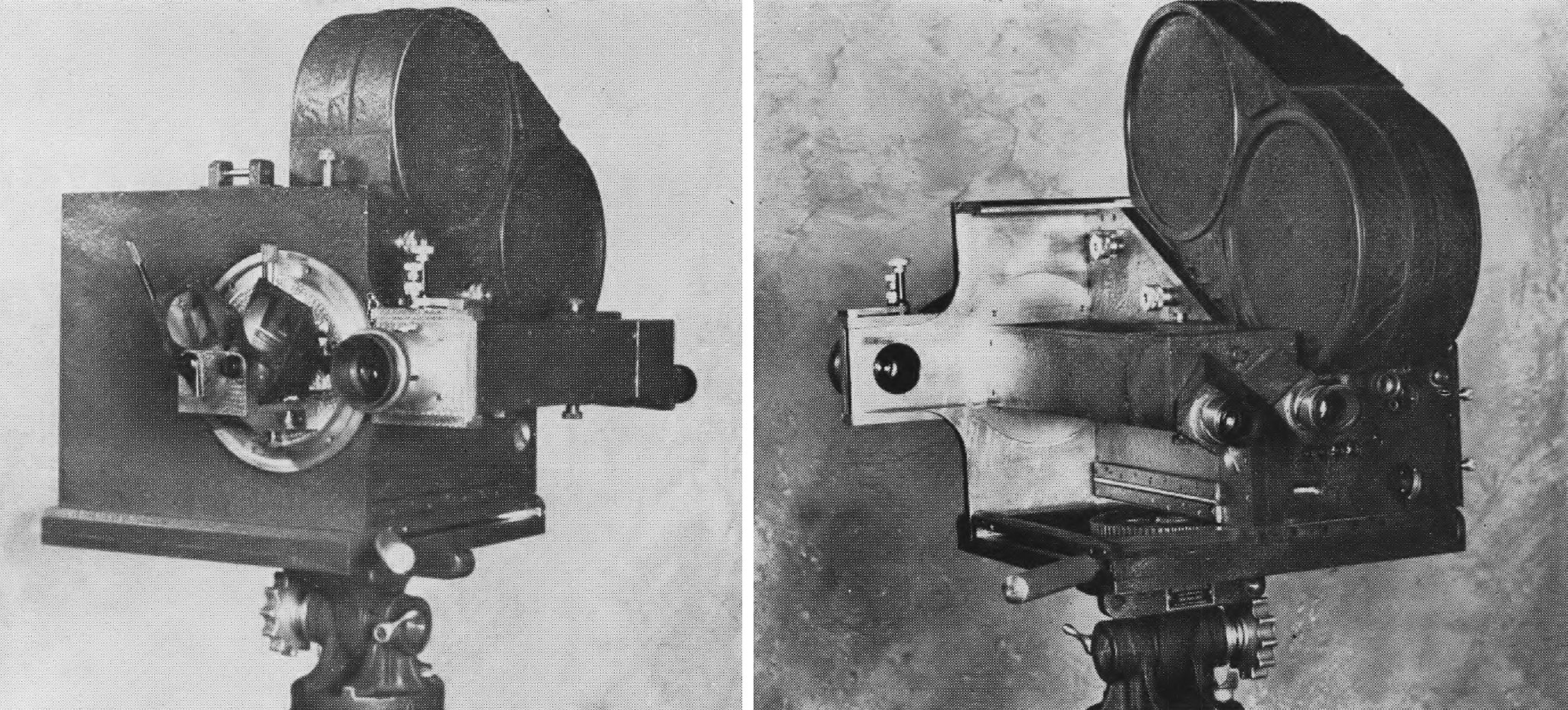

The camera assembly for the black-and-white picture consists of two Bell and Howell professional 35mm cameras mounted so that one was “upside down” in relation to the other. This was done so that the lenses could be brought close together.

Even with this arrangement, the interaxial was not ideal. It was fixed at 3.25 inches, although calculations showed that some scenes actually required as close as 1.5 inch interaxials. But no such camera was available then, nor was there time to have one built. However, a complete set of matched lenses of different focal lengths effected a quite satisfactory compromise with the ideal.

The greater part of the picture was a sort of fantasy, showing the parts comprising a Plymouth car dancing around and assembling themselves. Their movements were in synchronism with music and required the use of “stop-motion” photography, that is, “one-frame-at-a-time” shooting.

But a substantial part of the film contained “live-action” shots taken in the foundry and shops and along the assembly line. The narrator for the film was Major Bowes of Amateur Hour fame. He appeared in “live action” in one sequence in which he spoke. This was the first “live-action-live-dialogue” shot ever made in a stereoscopic presentation. It created some difficult problems since the cameras would not fit into any available studio “blimps.” However, the sequence was shot without any parasite camera noises being recorded.

Since the Chrysler film was shot in a two-camera setup, and no special photographic and projection facilities for single-film handling was available, it was necessary to project with two projectors. A rather complex Selsyn motor drive was used for interlock, although a much simpler synchronization could have been attained by a straightforward mechanical linkage, such as we used for the Pennsylvania Railroad’s stereoscopic movie display at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco in 1940.

A Technicolor film, using the stop-motion technique was our next stereo production. A unique filter attachment was arranged in front of the camera lenses. The filters were mounted on wheels which rotated together. Color balance was attained by making sectors having angular dimensions calculated to pass the quantity of light required for each color and as demanded by the sensitivity of the film.

The “A” (red) filter passed light to which the film was more sensitive than that passed by the “B” (green) and “C5” (blue) filters.

Consequently, the red filter had the narrowest opening of all, and the “C5,” to whose transmission the film was least sensitive, had the widest opening. The exposures were made by the alternate frame method of color separation. Three frames, one the red record, one the green, and one for blue, were made instead of one frame as in ordinary photography.

These separation negatives were used by Technicolor to make the printing matrices from which the dye imbibition prints were produced.

You'll find Part 2 of this archival report here.