Starship Troopers: Interstellar Exterminators

Cinematographer Jost Vacano, ASC, BVK and a team of effects experts conjure up marauding swarms of immense alien insects.

This article was originally published in AC November 1997. Some images are additional or alternate.

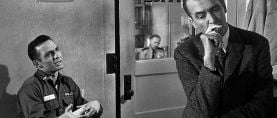

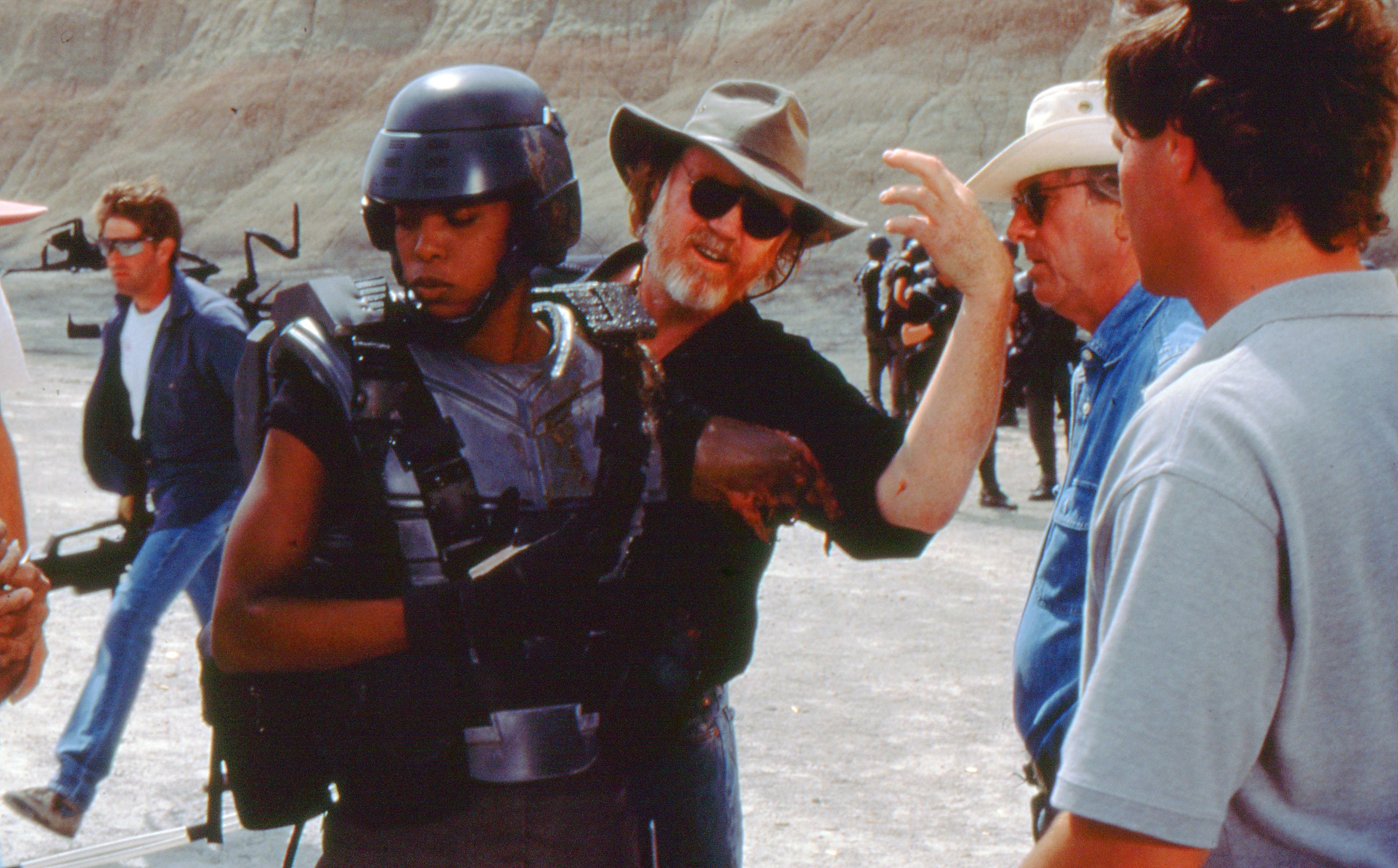

In 1959, science-fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein published Starship Troopers, an award-winning novel detailing Earth's battles against mammoth insectoids, as well as the lives of the soldiers who fought in the war. But adapting the epic scope of Heinlein's classic tome for the cinema necessitated nearly 40 years' worth of special effects innovations. The enormous amount of effects work entailed by such a project, however, is nothing new for director Paul Verhoeven and cinematographer Jost Vacano, ASC, BVK, who previously collaborated on the future-flung films RoboCop and Total Recall (see AC July '90).

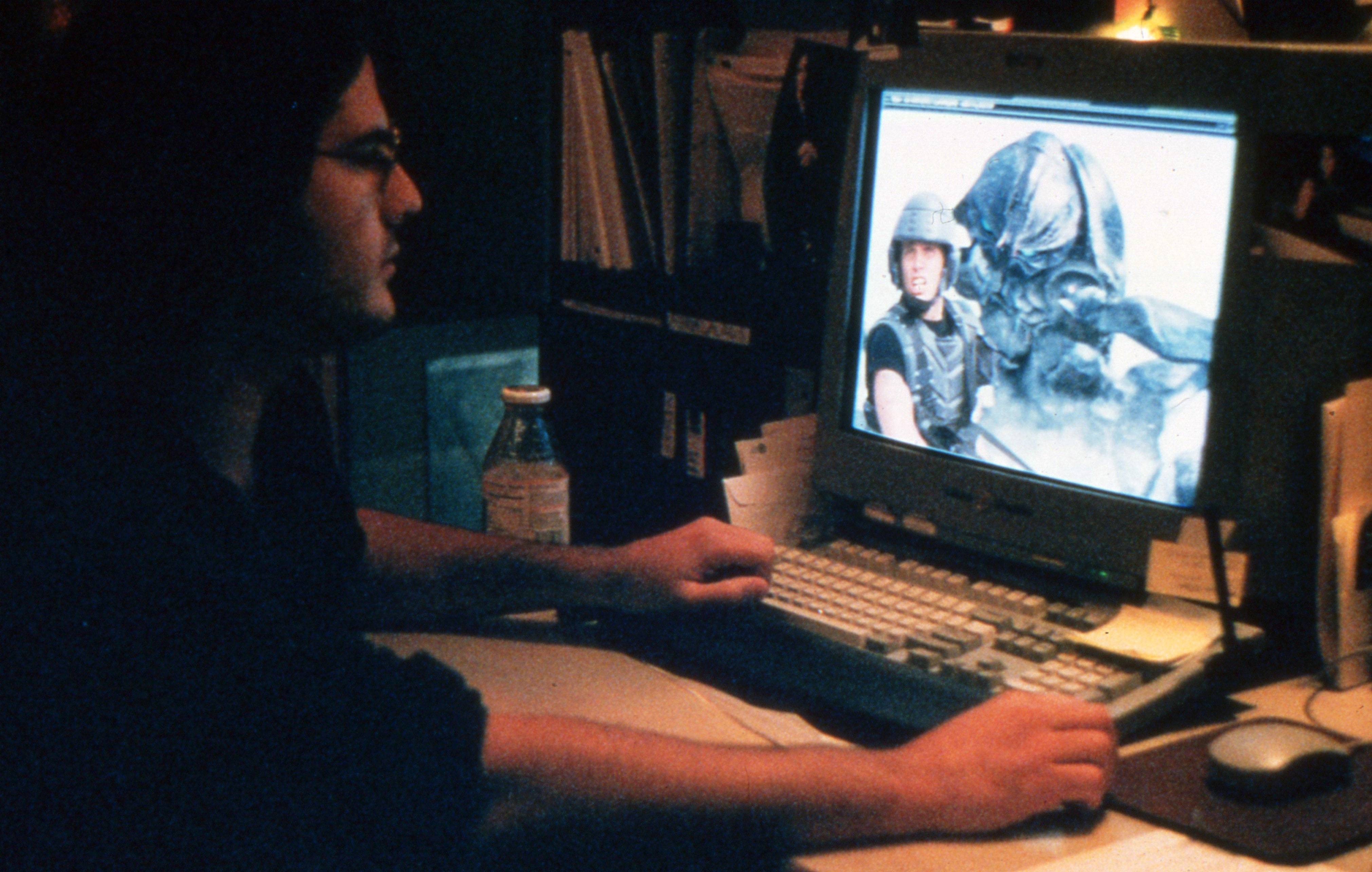

"What's unexpected in this film are primarily the bugs — they're the main actors," explains Vacano. "And they're coming out of the computer, which meant that we had to shoot things without having the main actors in frame — they were only in our minds. "Whether you're doing opticals or using computer-generated images, the procedures [for the cinematographer] are very similar," Vacano continues. "The main artistic problem is that you have to frame objects which are not there. You always have to keep in mind the size of the bugs — even the eyelines are important. You start working with cutouts, or long poles with flags on top, so you can determine the height of the bugs. This made it difficult for me, the actors, and especially A-camera operators Billy O'Drobinak and Mark Emery Moore."

Vacano is one of two cameramen employed by Verhoeven throughout his feature-film career in both Holland and America — the other being cinematographer/ director Jan DeBont, ASC. In the past, the Dutch director staggered his relationship with each cameraman: he would work with one on a pair of movies, and then switch to the other for his next two cinematic endeavors.

Born in Munich, Vacano began shooting for Verhoeven on the World War II-resistance drama Soldier of Orange, followed by the controversial coming-of-age film Spetters. Since their pair of aforementioned science-fiction epics, Vacano and Verhoeven have worked together on Showgirls (AC Nov. '95). The cinematographer's other credits include his Oscar-nominated imagery on Das Boot (AC May '97), The Neverending Story, The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum, The 21 Hours of Munich, 52 Pick-Up, Rocket Gibraltar and Untamed Heart.

With DeBont concentrating on his directorial career, Vacano may find himself shooting even more of Verhoeven's films, although the cinematographer says that he has found their existing arrangement to be quite satisfying. "Alternating every two years has kept our working relationship very fresh," notes Vacano. "Back in Germany, I had an experience where I worked for a director on maybe 10 to 15 films in a row. Working together too many times can be dangerous, because you start to develop a routine and you don't have to talk anymore. The cameraman knows exactly how the director will stage the action, and the director knows exactly how the director of photography will shoot the whole film. That can become a bit sterile. The way Jan and I alternated with Paul over the course of a two-film period always resulted in a fresh perspective and a new energy."

Location shooting for Starship Troopers in Hell's Half Acre (a county park west of Casper, Wyoming) and the Badlands of South Dakota began in March 1996 and lasted four long months. Hell's Half Acre is a remote canyon with strange rock formations — well-suited to depict Tango Urilla, an alien world where Earth's troopers make their last stand against the rampaging insects. The crew built roads which navigated to the bottom of the crevices so that the art department could erect the humans' command center; equipment not transportable by four-wheel-drive vehicles had to be lowered into the pit by helicopter. "That was the biggest set I've ever lit in my life!" Vacano exclaims. "Nightlighting a landscape is always a problem: it's usually lit by the moon or a distant light source. Whatever you can duplicate is always relatively close [to the camera]. This set was about a mile long and a half-mile wide, and it was absolutely inaccessible to Musco Lights; there was no way to get fixtures into that area. So we ended up putting about 25 6K HMI Pars on one of the cliffs by helicopter, and we staged the action in a way which never showed the top of that hill. Those Pars became our main lighting source, and we hid other lights behind rocks and on many other hills.

"Because the cliff with the lighting was otherwise inaccessible, we built a secure path so the electricians could climb to the top: it took about a half-hour to 45 minutes to get up there. The ballasts for the lights got very hot and stayed warm for a few hours after wrap. Attracted by the heat, hundreds of small, young scorpions took refuge on top of the ballasts. We called it 'Scorpion Hill."

Extreme, desert-like climactic conditions made for hot, dusty days and quite frigid nights. After two shooting days, the ballasts' sensitive electronics succumbed to the elements, causing one-third of Vacano's Par lights to go out. The production had to constantly fly in new fixtures. Later, two weeks of constant rainfall forced the production to evacuate the site. The crew took refuge in a warehouse, where, because the production was on an evening schedule, daylight interior scenes were shot at night.

Recalls motion-control operator Mark Hardin, "One night, we ran into a difficult situation where we had a very wide panning shot with the troops charging over one road, up a slope, over the top of the hill and down the opposite side. Because of the scope of the shot, we had to back everybody onto a little pinnacle so the crew would not be visible. The motion-control system was parked on a little horizontal pad; we had just gotten the shot and were starting to shoot the clean reference passes when it began to rain. We were down in these pits of bentonite, which is mined for use as an oil-drilling lubricant. As it started to rain, this stuff became very slick. For the next two hours we wrapped as much as we could out of there using four-wheel-drive Gators. Everything was coated with muck since it was just pouring rain. The stuff builds up on the soles of your shoes, so you're slipping around wearing six-inch Frankenstein boots. Then it continued to rain for the next two weeks. [When we got back], gaffer Jim Grce had miles and miles of electrical line buried, in some cases, under seven feet of mud." After the rains subsided, whatever couldn't be unearthed from the bentonite pit — be it cable, ballasts or cars — remained entombed in the area.

Prior to principle photography, the production team and visual effects crew conducted motion control and camera movement recording tests at Tippett Studio in Berkeley, California. Preliminary full-dress rehearsals were held in the East Bay suburb of Walnut Creek, using General Lift's motion-control equipment. Joe Lewis provided two RotoFlex Field Units with nodal pan-and-tilt rotators, encoded pan/tilt handles (wheels), and focus stepper motors with encoders. Each system was totally enclosed inside rugged, all-weather, rack-mounted systems containing a CPU, keyboard, accessory drawer and four Point Blank drivers designed by Steve Kosakura. "Someone dressed up as one of the soldiers and we did some pre-programmed moves using all of the digital markers that the CGI people used for tracking," Lewis recalls. "We used bright orange tennis balls for reference. We did a full rehearsal of all the procedures we would follow on location, because for this type of effects photography, you must have a complete slate and intensive camera reports that provide pertinent information: the time of day, angle of sunlight and camera position."

To facilitate their effects work, Tippett's crew had to map out Hell's Half Acre with an aerial radar-based scanning device prior to shooting. Notes Hardin, "This gave them a precise topographical mapping of the area's terrain which allowed them to identify various features in the landscape. Prior to that, they had placed sensor markers on those landscape features which stood out on the 'topo maps.' By using these features as target points, they were able to reference the camera position against their tracking markers from where they took their measurements. These tracking markers correspond to paths where CGI bugs would later be placed."

For first-unit photography, most camera moves were encoded live rather than preprogrammed. According to motion-control operator Mark Hardin, this process often left him feeling more like a "data sponge" than a programmer. "My duties consisted of recording and playing back the moves generated by the camera operator's pan and tilt, and the AC's focusing. This accommodated the CGI crew under the direction of Phil Tippett so that they could have accurate data to plug into their Softimage systems; every action on the background plate would have an equal reaction on the CGI data. Everything we did was replicated for both the first and second-unit camera packages with identical Kuper systems, pan/tilt heads, and drivers, so that everything was the same."

Hardin operated the first-unit motion control during the first 100 days of location shooting in Hell's Half Acre and the Badlands; I personally took over during the final two weeks. Portia DiGiovanni handled all of the second-unit Kuper systems operation in the desert, as well as the four months of live-action filming which followed on stages at Sony Studios in Culver City, California.

According to Joe Lewis, the second-unit camera operator sometimes preferred using an encoded O'Connor 100 fluid head instead of the typical wheels arrangement. The encoder was calibrated exactly to the motorized head so that 90 degrees on the O'Connor would equal 90 degrees on the Pacific Scientific stepper-driven head. The operator could then adjust the gain sensitivity and smoothness of the encoder. Noise from the steppers was not a concern due to the reverberation of live ammunition rounds taking place during the shots. Says Lewis, "Second-unit director of photography Anette Haellmigk would say which move she liked and we'd just play back the same move and let the actors perform to the camera move, especially when there was a shot involving pyro effects; special effects consultant John Richardson would have to time either an explosion or a squib to the move."

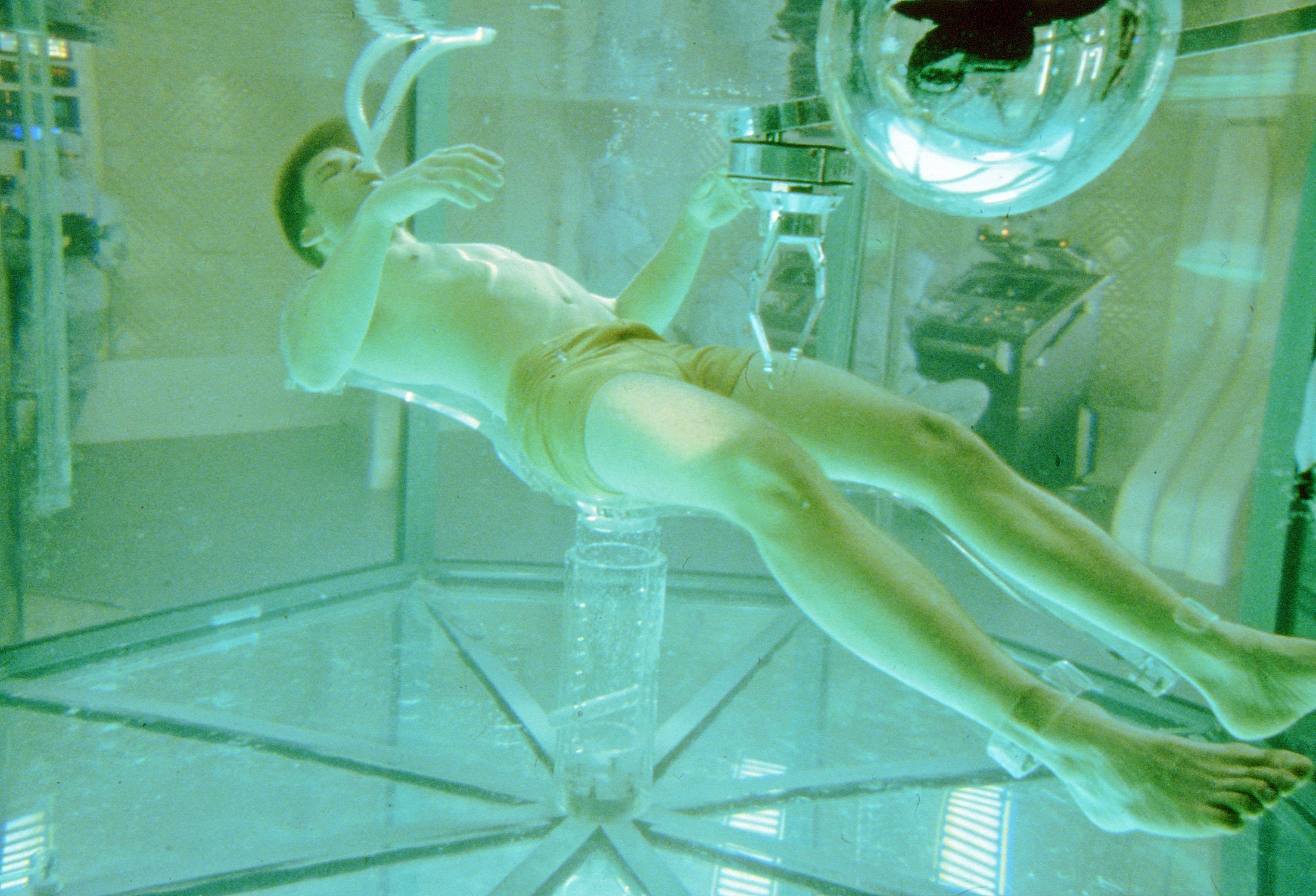

In another unusual effects sequence, Lewis' six-axis GenuFlex with track, boom, swing, pan, tilt and focus was utilized for a shot in which trooper Johnny Rico (Casper Van Dien) is having his shattered leg mended by an "auto-doc" robot. "We programmed a move starting from his head, down his body to his leg," Lewis explains. "The first pass was shot live; the second pass was done with a prosthetic leg featuring a huge, gaping wound so that Pete Kuran of VCE could later composite the two."

During shooting in Wyoming and South Dakota, the motion-control equipment was normally set up on the back of a four-wheel-drive RV unit so that it could be positioned anywhere on the location. When the RVs were unavailable, or the desert-like terrain became too rugged, the systems sat on Magliner hand-trucks and were physically muscled into position. "The systems could be set up fairly quickly," recalled Joe Lewis. "More often than not, we were ready before the first unit was ready to do the shot."

A typical shooting procedure began with the camera crew encoding a shot of the actors fighting the non-existent bugs. Selected takes were played back via motion-control and a clean pass was then made — sans actors — for background plate purposes. When time permitted, a reference pass with visual markers was also taken. Next, a large 18-percent neutral-gray sphere was rolled into the positions where the creatures would be composited into frame, followed by a exposure of a short burst of film (only a few frames were necessary for reference). The gray ball informed the 3-D animators of the exact light situation for that specific shooting time.

Elaborating upon this strategy, Vacano says, "You could see, for instance, if it was a side light or a top light. We could also look at the shadow areas, and also check the relationship between the bright areas on the ball and the fill light on the opposite side. This was very useful for Tippett, because he had to tell the computers exactly what the light situation was, where the key light was coming from [back, front, side], the angle of the light [top light for mid-day or low angle for close to sun¬ rise or sunset], the contrast situation [key-to-fill ratio, artificial or real fill light] or if they all had to repeat. Whatever we did, he had to follow [our setups] precisely, not only in the perspective and primary shooting angles, but even in the negative stock, so as to get the same image characteristics out of his computer."

Vacano and his crew primarily utilized Kodak's 500 ASA 5298 for night scenes and 50 ASA 5245 for daylight exteriors. Since each emulsion has a certain contrast curve, the effects companies needed specific logistical information regarding selected takes in order to create convincing CGI images and composites. Therefore, extensive notes on sun angle, compass headings, artificial-light inclinations and foot-candle readings were taken by a camera-surveying team, headed by Steve Redding and second-unit effects supervisor Jay Riddle. When the motion-control unit was inactive, we would fill in for people on his crew. In addition, Cathy Waterman operated an information-gathering device known as theodolite, or surveyor's transit. This instrument gave a very precise digital readout for pan-and-tilt, with a timed response metering device which emitted a pulse. By timing the pulse's return, the device could accurately determine the distance to any object.

"They would try to position the theodolite at one of the known landscape features identified in the topo flyover," recalls Hardin. "They would then place fluorescent-painted cubes and balls over the landscape where the bugs would be, and take theodolite readings to these reference markers and the camera. They lined up [the cross-hairs] on some specific target placed in the shot and, by aiming at that target, obtain a pan, tilt and distance measurement. When the shot was finished, we would set up another theodolite marker, which was a little prism device, on a machined mount that was the same as a standard dovetail plate mount. The camera came off and the prism was slipped on, placing it exactly in the nodal point for the given lens that we were using. We then took readings of that prism from the same theodolite position that measured all the other bug markers, so we knew where the camera existed in space. Using all of this data in conjunction with their Softimage software, Tippett Studio and the other effects companies were able to place their CG camera in space quite precisely in the same position as the actual production camera."

On a humorous note, military/technical advisor Dale Dye and some of the actors playing the embattled troopers regarded Tippett's personnel as the enemy, due to the fact that the then-invisible bugs were killing off most of their comrades.

A key logistical problem for the production turned out to be the sheer number of effects shots that needed to be done per day. Because of this workload, portions of Starship Troopers were doled out to nearly every California-based effects house, including Sony Pictures ImageWorks, Tippett Studio, Industrial Light & Magic, VCE and Boss Film. The extensive compositing schedule eventually led to the film's release date being pushed back from July 4 to November 7. First AC Greg Irwin comments, "On a lot of movies, you have one visual effects crew handling the effects shots. Here, the first unit was dealing with normal photography and the effects photography [at the same time], along with the different companies that were conducting the visual effects. The most fun part was in learning the different protocols that applied to each visual effects house. Tippett had one set of rules we had to follow to prep each shot, whereas Sony had a whole other set of criteria. We had to handle this on first unit in addition to normal photography!"

Vacano adds, "Each effects house has a different way of working; for example, one might prefer different negative stocks. Since almost every shot had effects, I would have to think: 'Is Boss or ILM doing this effect?' and then do the shot a certain way. That's unusual. Normally, one company will works exclusively on a film. We even had a continuous second unit for six months. Typically, you have them only for a selected period."

Given each effects company's preference for distinct film stocks and developing laboratories, Vacano found the film's timing process to be more laborious than usual. The various sources of original negative have lent a slight variation to the film's overall look.

Taking such discrepancies into account, the cinematographer offers this advice regarding the use of filtration in effects-laden photography: "Normally, you use filters according to the light situation or for a certain artistic effect. If you have a deep blue sky and a dark ground, you would filter differently than having an overcast sky, which gives much less contrast. The Badlands offered more traditional desert shooting — very rocky, with sandy colors. When shooting effects, it's always dangerous if you go too heavy with diffusion filters, because you always try to keep your negative as clear and as crisp as possible. It's always easier to degrade it later than to go the other way."

In addition to Vacano's own personal Arriflex package, which he prefers to use, the camera crew carried five other camera bodies used for special purposes: one Clairmont BL, one 4-perf Beaumont effects camera from ILM, a VistaVision 8-perf, and a Moviecam Compact for the Steadicam Pro system. Determining which camera body would perform a given shot depended upon which visual effects company would be compositing effects into the scene. "We mostly shot 4-perf for the CGI bugs [done by Tippett]," offers Vacano, "and 8-perf for the optical plates for Sony. But whatever perforations you're using, the registration must be extremely steady [which is why we preferred the Beaumont camera]. However, the production chose to shoot the film in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, and with the quality of digital effects today, 35mm 4-perf is good enough for many shots."

Vacano's preference for using his own camera equipment meant that all of his Zeiss prime lenses had to be pre-calibrated into the Kuper motion-control systems for focus information and exact field-of-view. "Even with three similar lenses, the field-of-view will always be a little bit different," he explains. "All lenses have certain tolerances, and when you're talking about a 50mm lens, there might be slight variances — one might actually be a 49mm, while another could be a 51mm. Maybe you'll find one which is exactly 50mm, but very rarely. So when Tippett is repeating things very precisely in his computer, he has to know exactly what the lens is, as the viewing angle always varies."

Before the start of live-action filming near Casper, Wyoming, Hardin and second-unit operator Portia DiGiovanni had a full day to calibrate Vacano's 15 Zeiss prime lenses and create focus tables. While this occurred, second-unit visual effects cameraman Rick Fichter, plate camera first assistant Michael "Spock" Bienstock and Joe Lewis performed an exhaustive nodalization for each lens. "We set up three Century stands at different distances from the camera [one close, the others far from the lens] in the hotel lobby," notes Lewis. "We then moved the lens along the Arri dovetail bridge plate and panned the camera until there was no parallax shift between the C-stands. We made markings on the bridge plate for each nodal position. Every rotator head was measured this way, and each plate lived with that particular head. Whenever we changed a lens, the camera position was physically moved fore or aft on the bridge plate so that it was as close to nodal as possible."

It's possible to check the field-of-view via a specified camera aperture dimension focused at a certain distance onto a chart with known object sizes. By entering the three known values, one can solve for the fourth using simple lens formulas, and then calculate the exact focal length. For a gate aperture of a given size and a lens of a given focal length, one can precisely calculate the horizontal and vertical angle of view necessary for the computer to know the proper image-size relationship.

Since lens focus barrels are non-linear and vary from lens to lens, each lens had to be calibrated in feet. That way, the CGI crew would later know where the taking lens was focused on the subject at any given frame during location shooting, without having to recalculate the position. This special task called upon the Kuper Table Axes function. By making a master axis of 200 frames for each lens, an actual footage graph can be slaved to this master axis. The footage axis "looks up" its position on the graph for any given focus position from a "special table file" move. Wherever the camera assistant moves the encoder, the stepper motor on the lens will follow suit and the pulses will be output in feet to a separate unused channel in the Kuper 24-channel software. This can be then saved (with the pan/tilt degrees information) as an ASCII move file for position reference on a frame-by-frame basis.

The Kuper file conversion is able to save the move information with the "center data on blurred image" (or shutter-open position), which follows the conventions of a computer graphics system. This will produce the best match between photographed and graphic image — the CGI will be centered on the image blur of the "live" photography. But Tippett's crew wanted more positions per frame than the standard single position-per-frame offered by the Kuper software. Thus, when saving a move in text format, motion-control operator Mark Hardin changed the data/visual from a shooting resolution of "four" to "one," which increased the total frame count by four times the normal move length. This allowed four position counts per move frame, which was a more than adequate reproduction for computer generated images.

Though the preparation for and data gathering required by the Troopers effects teams was daunting, the technology created unique opportunities for the filmmakers — especially when they were faced with unavoidable problems. Greg Irwin remembers a very impressive effects shot that occurred early on in the shoot. He details, "Day three required a Power Pod — a normal 'hot-head' crane — to which we mounted a Beaumont 4-perf effects camera. We tried to do a manual camera move in the 30-mile-per-hour winds that are inherent to the Wyoming plains. Tippett had to scan each frame of this 'wild' crane move to absorb the shake out of the camera as it was blowing in the strong wind. The final shot depicted thousands of these creatures swarming over the hill onto our heroes. Everyone was afraid of that shot, and we did it on the third day when nobody really knew what they were doing yet. The shot is in all the trailers, though, and it's awesome! Every arachnid warrior has a shadow and a dust cloud coming up as they storm the alien landscape." This shot demonstrates the true value of modern computer technology; even if there's an unstable crane shot, one can track elements in the frame and make it seem steady.

For "wild" shots not requiring motion-control, Tippet's crew had to amass data on solar angle and trajectories. For these non-motion-control shots, the camera operators needed to keep a certain number of reference markers in frame for Tippett's animators. According to Steadicam first assistant Todd Schlopy, this was more difficult when shooting Steadicam at night, since the gyrostabilized rig's CRT monitor is basically a black-and-white screen — which made it problematic for operator Mark Moore to ascertain whether or not the small squares and triangle targets were in frame. "The Pro model suspended camera system offers a superior viewing screen, however, and is more trouble-free when shooting in extreme locations where dust is prevalent," Schlopy maintains. "We reloaded inside a tent just to keep the dirt out of the cameras — especially the Beaumont, which is a very sensitive piece of equipment. In the Pro model, if something goes wrong, all of the electronics are contained in one simple monitor — you just slap a new one on. The batteries are excellent, and there are gyros available now. It's just an outstanding Steadicam setup; it really gives you many options as far as shooting. You can use whatever camera the arm can handle: 4-perf or 8-perf. There is a new arm coming out that will even accommodate more weight."

In spite of all the technical travails entailed in making such a complex and effects-reliant film as Starship Troopers, not all crewmembers found the grueling hours and difficult situations to be disheartening. Comments first assistant Irwin, who also worked with Vacano and Verhoeven on Showgirls, "I think Troopers is the most fun we've ever had, and the most we've ever gotten into photographing a movie."

You'll find a complete story on the film’s creature effects here and the film’s starship effects here.