Sophisticated Visuals on Grand Scale for Die Hard

The team from Boss Film Effects details just how they were able to blow up Nakatomi Plaza and throw Hans Gruber out the window.

Photos by Virgil Mirano

Richard Edlund, ASC, producer of visual effects, views the popular success of Die Hard with well-earned satisfaction. A hard-hitting suspense melodrama about a lone policeman's battle to overcome a band of professional terrorists who have taken over a towering office building, the picture is not what we generally think of as a special effects-oriented show. It takes place in modern, workaday Los Angeles and there are no aliens or monsters, no pseudo-scientific gimmicks, no flights into outer space or visits to long ago or far away worlds. The story, however fanciful, is grounded in reality. Most of it was photographed at night in and around the new 34-story Fox Plaza Building, which towers over Century City, California, and on a spectacular interior set a few hundred yards away on Stage 15 at Twentieth Century Fox Studio. Two Musco Lights were used in illuminating the actual building and adjacent areas.

Much of the essential action of the story, however, could never have been translated into motion pictures without the utilization of highly sophisticated special visual effects conceived and executed on a grand scale. Edlund, who began his visual effects career at the studio of Joseph Westheimer, ASC, made his name at Industrial Light and Magic on the likes of Star Wars, China Syndrome, The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Poltergeist, and Return of the Jedi. About four years ago, he established Boss Film Effects, from which have emanated the effects for Ghostbusters, Fright Night, Poltergeist II, 2010, Big Trouble in Little China, Masters of the Universe and now Die Hard. In the course of these and other ventures he has amassed four Oscars, four nominations, three Academy Scientific and Technical Awards, and a head-full of know-how. His crew ranges from 60 to about 170 experts in the various arts and crafts that make up a complete effects team.

“We had to pull out all the tricks we've come across in our years of experience for Die Hard," Edlund remarked after the picture wrapped. “There are 35 or 40 effects shots involving about six months of focused involvement. It was fun working with John McTiernan, the director, and Joel Silver, the producer. For one thing, Joel requires an attitude of exaggerated reality, and he knows that to make an audience whoop and holler you really have to sock it to them. Even though the picture is very violent, it's stylized in such a way that I can appreciate it. The last person really capable of doing that was Sam Peckinpah, whose violence in The Wild Bunch was outrageous, but it was stylized in such a way that it was engaging.

“It takes a team effort to make any movie, and it certainly shows on this project. Joel has a group that has worked with him on several pictures and it's really important to have that kind of team. I have that same luxury here - to have fabulous people who have worked together for a long time and really know how to think on their feet and can come up with an answer right now when it's necessary. We try to make the movie the best way we can, so I don't try to steer the director into making everything into another shot for us — there'll always be plenty of work for us. Al Di Sarro, who was the production effects man, did a number of the shots that have big explosions on the building, such as the long shot where you look across the city and see a big explosion on top of the building. He did that — safely — and they just shot it. But you can't blow the top off of a real building, so when that happens those are our shots." Brent Boates, Boss visual effects art director, worked with McTiernan to design these shots.

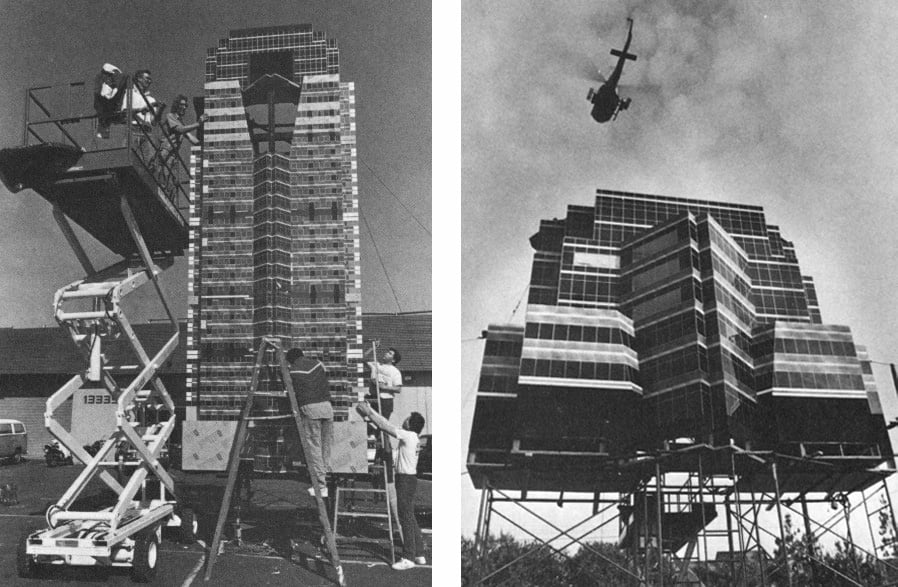

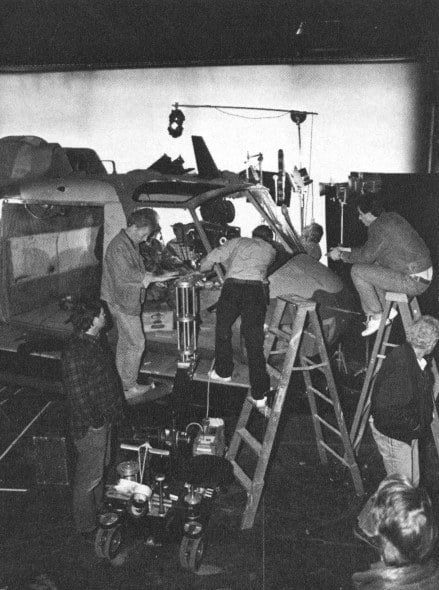

top floor of the model.

preps a larger

version of the helicopter for cockpit

closeups

The scenes in which the top of the building is blown up, which also involves helicopters, one of which first attacks the building and then is destroyed in the explosion, demanded some unusual techniques. Many of these involved miniature settings and models, which were built in house under the supervision of Mark Stetson, of Blade Runner, 2010, and Ghostbusters fame. Edlund described the complexities of the work:

“We could fly the helicopter down the main streets of Century City and then make a right turn, but we weren't allowed to get within 200' of the building. The scenes inside the chopper were all bluescreen shots that we did at Boss, then we did the background plates from the helicopter. Our director of special effects photography, Bill Neil, made the helicopter shots with the 65mm camera handheld on a Tyler mount. He cheated by using a longer lens to bring what's outside the windows in closer. We had a nose mount underneath the chopper for certain approach shots. Because of a logistical problem, we missed getting one particular plate which was crucial, so we had to use another plate and do a reverse action and flop it to make it work for that one shot.

“There was one shot, where we were looking at the top of the building when the explosion went off just before we cut to a shot of the helicopter coming toward us, which was actually a 35mm shot from production. There was no explosion on the roof, however, so we had to add it in — that was an afterthought. One helicopter was fairly high above the building, and the other copter was in front of the building with the whole of Century City and Los Angeles in the background. We had to rotoscope the helicopter in front of the explosion. Also, there was a camera move in the shot, and that identical move had to be in the explosion as well, so it was a tough one to shoot."

The miniature explosion work was by Thaine Morris, named by Edlund as “the best — I've worked with him since The Empire Strikes Back. He knows how to make the explosions look right as to color and speed, how to slow them down properly for scale. We had to do a little bit of printer correction to get the explosion to match, then do rotoscope mattes from that and then composite it. Then the flame had to engulf the helicopter, so there was another sub-rotoscope where there had to be a ball of fire placed just right within a bigger ball of fire. Only Thaine could do those in miniature, position them and know which part will be bigger than the other. That's pretty esoteric, like trying to control wild stallions."

The best of these shots, Edlund feels, brought him a phone call from producer Silver: "That shot is totally legitimate! It's one of the best you guys ever did." Edlund described the scene: "You're looking up at the top of the building, where there's a huge fireball. The helicopter comes spinning out of the fireball, falling towards camera. The fireball then has another sub-explosion going on within it as the helicopter continues falling. Then the helicopter blows up on its own. It was all done in the camera with no added effects; Thane and Bill did it all. The building was a miniature. The helicopter — quite an expensive unit — was radio controlled. We had three shots at this, at $3,000 to $4,000 per helicopter; they got it on the second one and it was magnificent. Everybody was out there watching and there was no question in anybody's mind at that point. We shot a videotape of it in real time; it falls over, bam, and it looks funny on film. It was shot at about 240 fps, not at top speed — we eased back after doing some tests to check the speed. It was a difficult and relatively expensive shot to set up, but not prohibitive."

At Boss, almost all effects are shot in 65mm, which offers a large image area with which to work. In this way it is possible to produce composites of such high quality that when reduction dupes to 35mm are made, the effects shots don't suffer when intercut with 35mm production footage. As Edlund explained, "Anytime you're creating visual effects you want to begin with the biggest possible negative because you're going to amplify image problems with each succeeding generation.”

Die Hard was photographed with anamorphic lenses, which has been known to create problems in visual effects production. Edlund, however, expressed a liking for working in anamorphic format. "I think it's a much more dynamic aspect ratio. "It's more 'big movie'-like, the way God wanted pictures to be made, and it uses all the 35mm negative. With 1:85 you're throwing away much of the negative, although with spherical lenses you end up with a better depth of field. A lot of people confuse depth of field with sharpness. Anamorphic is more difficult to compose for, but there are a lot of cinematographers who know how to use it, and it does provide some problems for us, but we've learned to deal with them.

"Actually, it makes our material look better; look at the quality in Die Hard. Jan de Bont is a great cameraman and he was able to produce a really lush, rich look even though it's high-speed, low-light photography. He shot the entire picture on Eastman 5295. Our effects shots cut in seamlessly and you don't see any dupey quality. Oftentimes when you dupe in 35mm you get a scene that looks dupey and it doesn't cut in right with the rest of the scenes. In Die Hard there are eight or nine shots that were done as 35mm composites. What we do sometimes to avoid that dupey look in 35mm, especially for titles, is to use two interpositives. That's a technique we tried first on E.T. when I was at ILM — we used two interpositives at 50/50 exposure. I've always disliked using CRI [color reverse internegative] because it has a sort of swimmy grain look. The last dupe I remember that was really hideous in that way was Kramer vs. Kramer, which was beautifully photographed by Néstor Almendros, but the grain in the release dupe looked like golf balls. A lot of times I see movies in the answer print stage and sometimes it's quite a comedown later to see that 35mm release print look."

Some of the most suspenseful moments in Die Hard involve vertiginous sequences in an elevator shaft. Most of these were produced as visual effects shots for several reasons.

"Just looking down the elevator shaft provided an incredible lighting problem, and beyond that elevators are controlled by codes and you certainly can't explode anything in a real elevator shaft," Edlund reminded. "The fact is that a lot of damage had to be done to the building in the course of the story, but none of it could actually be done to the building. We were called upon to do all of that. The elevator shaft we wound up building was a forced perspective miniature about 20' high. It was built like a funnel, so that it was narrow at the bottom and wide at the top. It provided a good way to avoid having to build a 40' tube in order to shoot the elevator in miniature.

"This also provided some problems for Morris, our pyro-master, because the explosion in the shaft has to start small and get larger until it fills the frame. The explosion had to be shot separately. First, we shot a plate of the forced perspective miniature with the lights on; then, without moving the camera, we turned off all the lights and shot the explosion in the tunnel as a separate piece. Actually, we shot a couple of different explosions, then had to composite them together in order to get the final push that knocks Bruce out and kicks out the windows — which is a climactic point in the movie. What we wound up with is a composited piece with Bruce in the foreground shot against a bluescreen as he scrambles out of the way, and the two explosions matted into the tunnel. It was a lot more complicated than it appears to be, which is sometimes the case in effects work. I think it is really Thaine who deserves the big hand for this, because he was able to create explosions in miniature in a fairly small size that look really big and amazing." Neil shot this sequence by ramping down the camera speed in order to enhance the speed of the oncoming disastrous fireball.

Another audience grabber is a sequence in which Willis tries to climb down to a ventilation shaft which opens into the elevator shaft. He falls and, unable to grasp hold of the vent he was attempting to reach, plunges toward certain death. He saves himself by hanging onto a shaft farther down. "Most of that was done live," Edlund recalled. "Neil, Boates and I were advising John in ways that we felt would give him the kind of verve the shot needed by using a forced perspective painting or actually building forced perspective sets. I think if we had done it as a miniature it would have carried more depth and might have looked more precarious, but the way Bruce played the scene and the way John directed him, I think, pretty much got the max from it. It was really a gut-wrenching sequence."

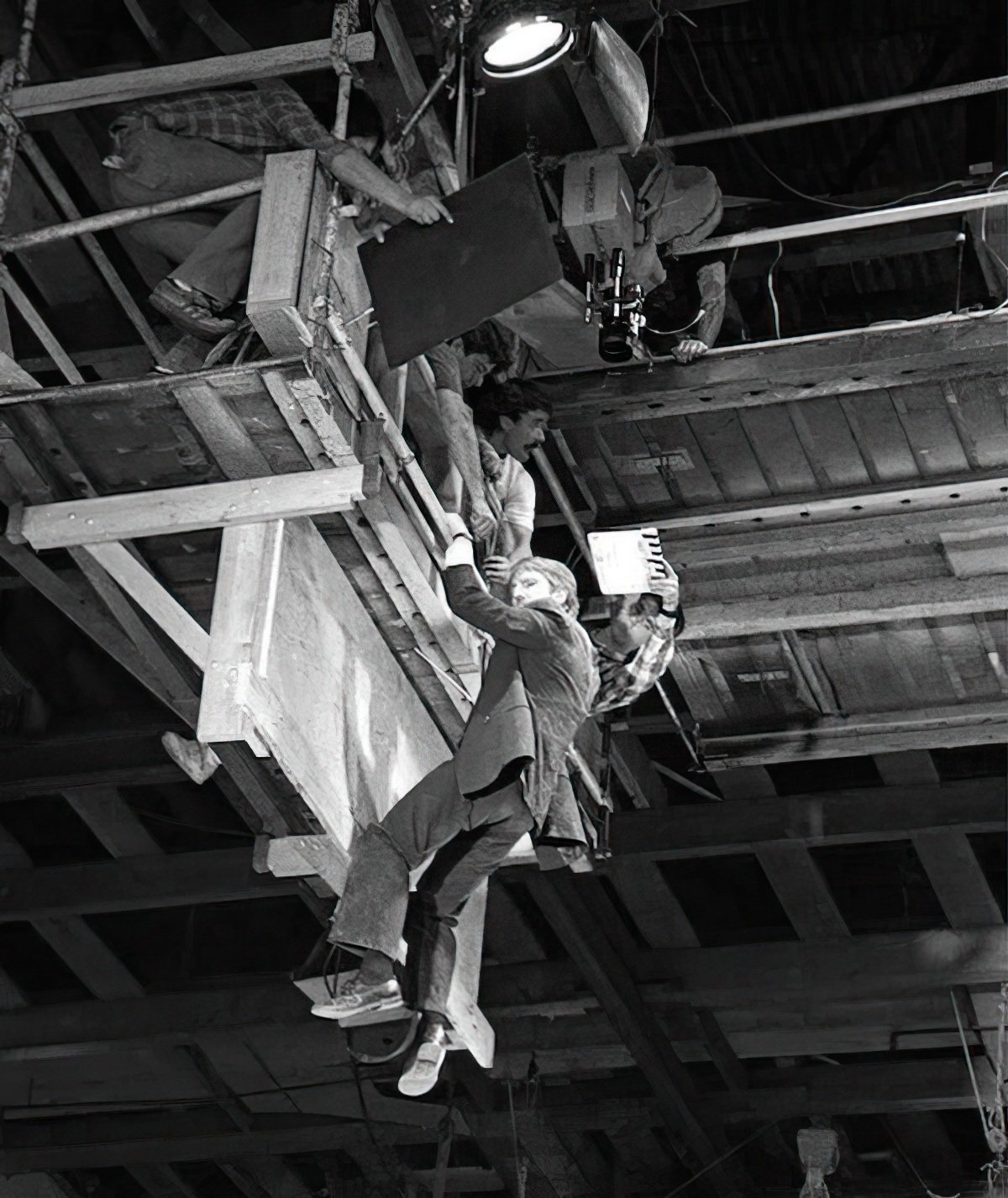

Yet another scene guaranteed to induce acrophobia begins as a close-up aiming down at the principal villain, played by Alan Rickman, who is clinging to the edge of the skyscraper roof and trying to aim his gun at Willis. Then he loses his grasp and falls away from the camera, into a terrifying void backgrounded by the street action hundreds of feet below. Slow motion photography stretches the suspense of the moment to the limit. It is reminiscent of the celebrated scene made by John Fulton, ASC for the Alfred Hitchcock picture Saboteur, in which Norman Lloyd falls from the torch of the Statue of Liberty.

"Our villain actually fell about 20' into a huge blue backing on a stage at Fox," Edlund revealed. "It was a pretty large setup with a lot of nine-lights illuminating the backing. Bill used a follow focus device which lets you pan a video camera on the actor and keep him lined up in the crosshairs, and it is calibrated to the focus mechanism in the taking lens. Rickman was falling away from the camera, and, of course, it all happens in a few seconds, but shooting at 300 fps lengthens that by a factor of 12. He did it five times, too. We were able to use the shot only until he fell into the path of the lights illuminating the bluescreen. McTiernan loved the shot and was pleading, 'Can't we get just a few more frames?' The action was shot in 35mm anamorphic and then composited optically against a 65mm background."

Boss Film uses Eastman 5247 and 5295 for bluescreen. "We love both — 47 is a magnificent film and 95 is tops for our work," Edlund said. "We've gotten away from 5294 — although it can look very good — because we find that we like 95 better. Unfortunately, this leaves us with quite a bit of 65mm 94 in the freezer."

Stetson's model crew at Boss made three models of the Fox Plaza, ranging up to one about 25' high. These substituted for the actual building for several key sequences and, in one instance, the larger model was combined with the real structure by a complex process.

"There's always one shot in any movie that is hard to get just right," Edlund said. "It turns out to be the most difficult one, but you never know which one it will be. Sometimes it's a shot that seems simple, and there'll be some particular trouble with it. We thought it was going to be the aftermath shot, in which we tilt down from the top of the building, which is on fire and spewing an enormous cloud of fire and smoke into the air, down to the incredible chaotic mess at the bottom of the building, with firetrucks, the cops, the FBI, and smoldering helicopter remains. All this plus thousands of reams of paper that were floating down out of the sky like snow. Certain parts of that — some of the falling paper and the action on the ground, for example — were done live. Di Sarro had guys at about the 10th floor of the building throwing off paper, but they proved to be a problem visually because it was so sourcy; you could see that the paper was coming from one area on both sides of the building. On the other hand, when we were down low, at the end of the shot, we needed the paper those guys were throwing, so we shot that from a Titan crane. It was not done with electronic motion-control equipment but was a simple tilt down with an O'Connor head, traveling from the top to the grounds with all the people milling around, then we boomed out around some trees and really gave the audience a good look at the mess.

"The beginning of the scene — the burning top of the building - was a miniature, and then we had to match that tilt down, which was shot wild, and then go into the boom shot. It's the kind of shot that makes you say, 'Oh, God, are we sticking our necks out too far?' One of the difficult things to line up is patterns; if you have objects that are broken up or organic shapes, it becomes fairly simple. But if there are patterns, it has to be absolutely right or you start seeing a disparity, and if the pattern shifts during a dissolve, then you've given yourself away. In this case there was a point where we could dissolve off the building and get away with it because it was darker, but there was a problem in that there were various lights on in the building, so the lights had to be dissolved on. We came up with a whole series of 'sleight of eye' techniques involving the falling paper. Initially, we were going to use paper falling to cover up the transition, but it turned out that the lineup was so good on the shot that we didn't need to do that."

Edlund used the evolution of the sequence to illustrate one of the facts of life for effects men. "Oftentimes you start off with a concept and when you get into any given shot it takes on a life of its own and dictates what you must do to fix it. It's one of the challenges I find most interesting in effects work. You start off with a good idea and try to control everything, but somewhere along the line you have to shift gears because of circumstances unforeseen. You have to be able to think quickly, so that you don't shoot something that you can't fix later. You're really putting yourself on the line on the set. The pressure is very high when you're shooting background scenes and plates, because a night shoot with a full crew costs maybe $75,000 or more, and you're taking up two hours of that night to do that shot, trying to coordinate all these people with walkie-talkies and bullhorns. The only way to do that is to have a really good crew that knows how to run with the ball.

"That was an interesting shot and a complicated one which certainly wasn't like falling off a log, but it wasn't the most complicated or difficult shot," Edlund averred. "The shot that turned out to be the toughest was the one that came in last — the third-floor explosion. That happens right after Bruce gets kicked out of the way by the explosion that came up the elevator shaft and it blows out the whole front of the building. Cut to a shot of the building, with a smoldering armored car down at the lower left, and — BOOM! — all of a sudden the front of the building blows up."

Originally, Neil had photographed a test explosion before making several additional takes, always with the knowledge that a matte would have to be extracted from the explosion to be printed into the relatively bright pattern of the actual building.

"The explosion that McTiernan picked was the first one we did and, because it was meant only as a test, the lineup wasn't quite right," Edlund recalled. "He said, 'I like that explosion; can't you use that?' I said 'okay,' because even though it was a little crooked, it actually was the most dynamic shot. But it had a big dark spot of smoke in one part of it, which meant that we couldn't get a matte from it. When we got it into opticals there was no way of pulling a matte out of it, and you can't really rotoscope explosions — it just doesn't work. We had a big transparent spot right in the middle of the shot, and your eye goes right to that you say, 'Why is that transparent' instead of being knocked back in your seat, which was what this shot had to do. Joel was relentless: 'It's got to be great!'

"Dennis Michelson, our visual effects editor, picked out frames for us. Editorial is really pivotal in this field in terms of getting all the different elements to work and being able to pull out little tricks at the last minute. He had to find frames of explosion that could be flopped or manipulated in order to get them into the right position to composite together with the first explosion. Because this was shot in 35mm anamorphic, we didn't have a lot of repositioning capability. Then it went in to Al Cox, the optical supervisor of this show, whose nickname is ‘Diehard’ because there was so much difficulty in getting all the scenes to look real, getting the matches perfect, doing focus changes on miniatures in the background, and working with focus changes that were done on the plate. Also, there was a lot of tricky things that were sort of thrown away as part of the shots, but these are the kind of things that can be done with a live camera and if you don't do that with the effects shots the audience starts being suspicious, even subliminally.

"The director wasn't going to let us, or the audience get away with that, so he pushed us to the limit in getting all these little tricks out of us," Edlund grinned. "He came up with a number of demands, but they were demands of a creative nature and we appreciated that. In any case, Al was able to put the incredibly complicated matte together in stages from all these 'grab a frame here — match it to this shot over there' elements, and it would have looked terrible if we hadn't done those six or seven frames of fix.

"So, that was the last shot. It was redone and redone and redone. It took eight or maybe nine takes to get it right. We got that transparent spot out by taking frames from different takes and finding those frames that would work and putting them in, but the main thing was to make the matte and then put in all those frames. Many had to be re-positioned, so we'd have to remember that on this particular frame your matte was made 115/1000ths to the left, and that means that when we'd burn that frame in later it would be necessary to move it 115/1000ths to the left so that it lined up with the matte."

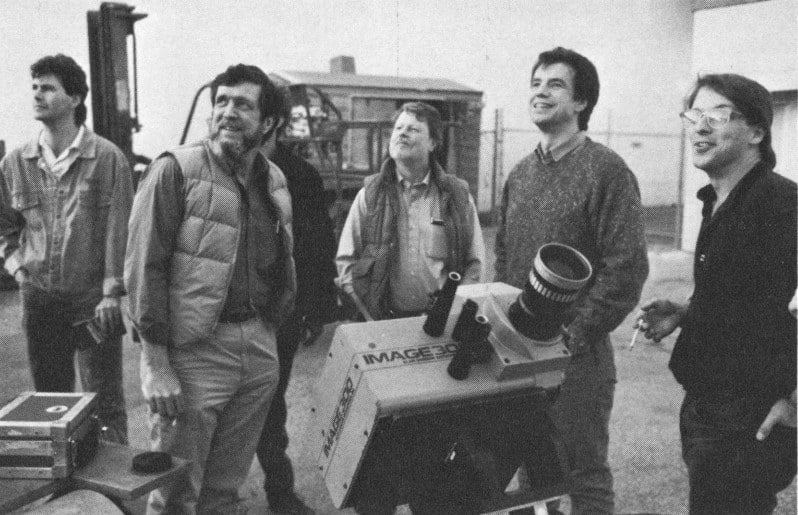

Die Hard. From left to right. Stetson, Edlund, Neil, McTiernan, and Boates.

Much of the credit for such complex opticals belongs to the ZAP (Zoom Aerial Image Optical Printer) which brought Boss an Academy Science-Technical Class Two Award in 1987. It was built originally for Poltergeist II. "ZAP gives us the ability to do things that give us the edge in making a movie like Die Hard," Edlund said. "To some extent the essence of a good optical printer is reliability and repeatability. If the operator — the camera artist, actually — who is compositing shots makes a fit and saves those numbers in the computer, and goes back later on and can't trust those numbers, then he's limited as to what he can do. Then he doesn't make that move and you end up living with something that's less than as good as it can be. If he can really trust the machine, knows that it's stable and sharp and that it's going to do the same thing each time, he has the same facility that he'd have with a pencil when making a sketch.

"With the ZAP you can actually make off-center zooms on all the separate elements on different passes, and they all line up. It's repeatable within less than 1/10th of 1000th. There's a corkscrew/cam arrangement that moves various elements at different rates of speed and continuously reconfigures all the lens elements inside. It can make pans, tilts, and zooms on a particular blue screen shot, for instance, and then make the separations, cover mattes, intermattes, and all other elements on separate passes with that same move. They all line up without fringing because it's extraordinarily precise. Concentrating on producing really good equipment for the people who know how to operate it gives the ability to push into areas that others may fear to tread. It's a one-of-a-kind piece."

Astonishingly enough, the scene in question was a very quick shot, only about 35 frames long. Yet, it had to be perfect, according to Edlund, because a modern audience comprehends the contents of a scene much faster than viewers in the past. "The audiences nowadays picks things up in two frames. When I first started studying film there was a book by Raymond Spottiswoode called The Grammar of the Film, and it was my bible. I found it in the base library in Japan — the only book on film there. He had done a graph on how long it takes an audience to recognize a new shot; he said it was 1/5th of a second. In other words, there was that much time lost at the beginning of a cut because it took that long for the audience to become accustomed to the next shot.

"It's more like 1/25th of a second now because the audience has become so attuned to watching film shot at 24 fps that their perception of reality is based, in some cases, on having seen film. The average 10-year old has seen millions of feet of film and knows exactly what something looks like, and if it doesn't look right becomes suspicious. Television commercials reflect the capability of the audience to glean information in a very brief time. It also depends on the type of image. Certain images are more recognizable — if it's muddy they don't pick it up, but if it's sharp and has good edge kicks and contrast, they get the point quickly.

"There were all these throwaway shots that could never be done, and yet they looked real," Edlund continued. "We did a lot of shots that will go by and nobody will ever know they are effects shots. That's the way it's supposed to be."

Edlund would go on to receive his 10th Oscar nomination for Best Visual Effects for his work in Die Hard, and he would add an 11th for Alien 3 a couple years later.

In 2007, he was awarded the John A. Bonner Medal of Commendation from the Academy, and in 2008 he was honored with the ASC President's Award for his outstanding career.

You'll find our podcast with Die Hard cinematographer Jan de Bont, ASC here.