Shadow of a Doubt: Using an Actual Town Instead of Movie Sets

“Now that we’re limited as to set construction, we may find on our part that while we’ve lost something we have considered indispensable, we’ll have gained an element of realism which will more than offset it.”

Editor’s Note: During World War II, the rationing of materials for use in the war effort led to strict budgetary restrictions on the building of new sets. Also, exterior lighting after sundown was limited due to concerns about enemy attacks. This article in part addresses those production issues of the era.

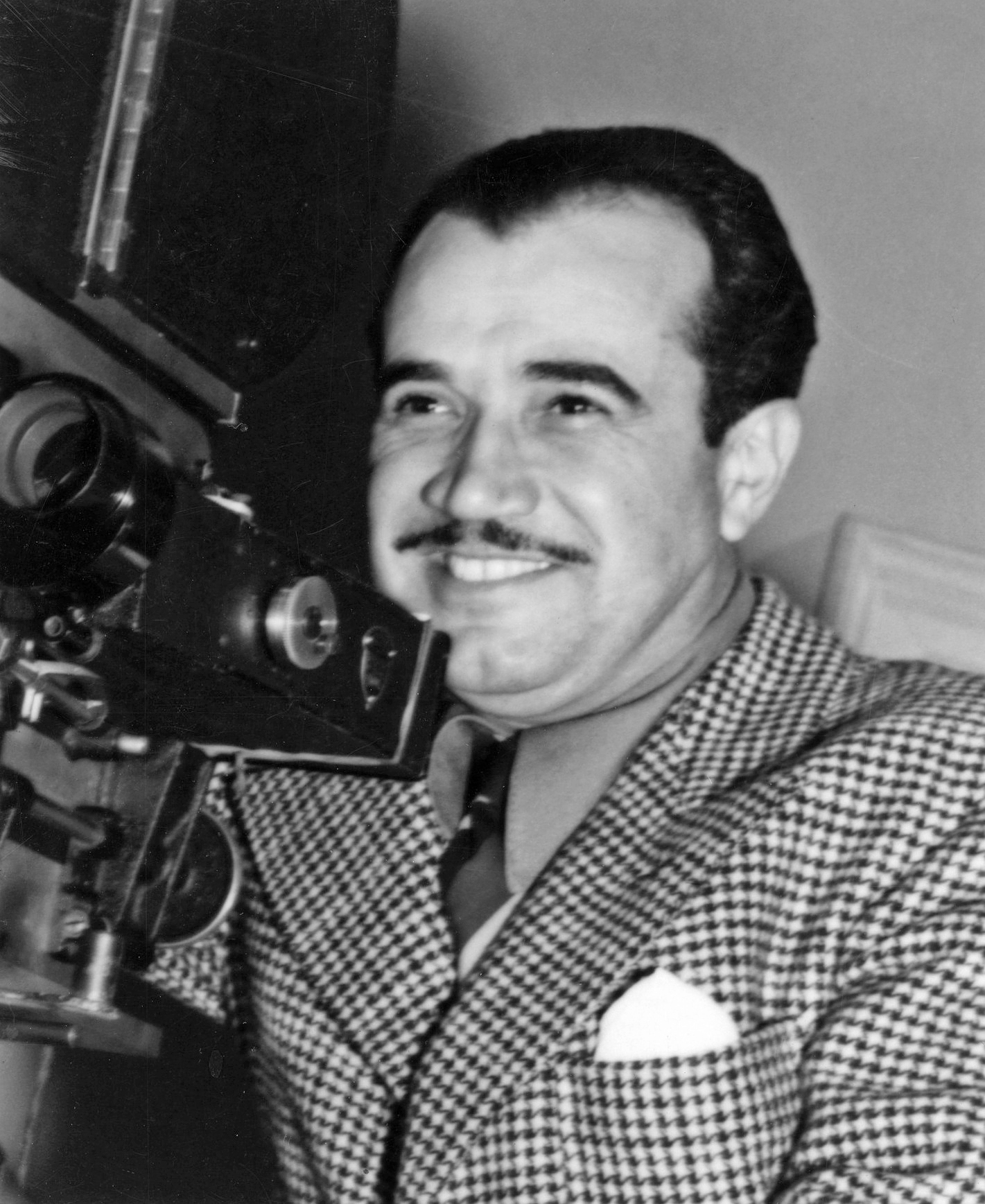

By Joseph A. Valentine, ASC

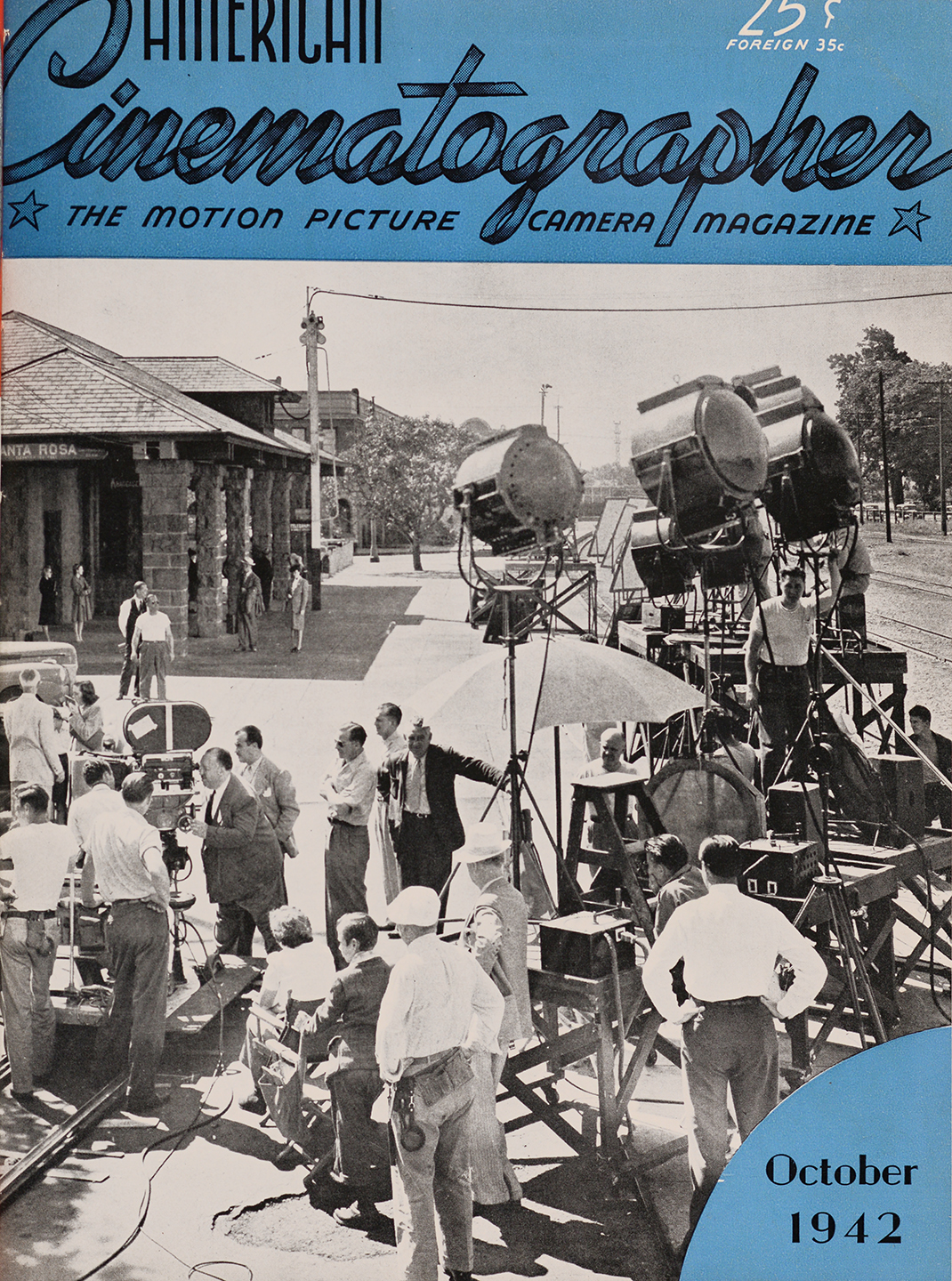

Photos by Edward T. Estabrook

The whole of an actual town used for a movie set! Backgrounds which, if duplicated in studio sets, would have boosted the production’s set budget into fantastic figures, even for a major studio production! Intimate scenes, both exteriors, and interiors, photographed against authentic backgrounds which would put to shame the best art director’s attempts at realism!

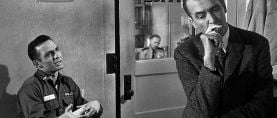

That is the experience I have just had during four weeks of location work in Northern California filming Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt. For four weeks we worked in the town of Santa Rosa, filming both day and night exteriors and a surprising number of intimate interiors as well, against the background of an actual and very typical American small city.

After viewing the rushes I’m convinced that “Hitch” has really started something in pioneering this idea. Not only have we given our picture its background on a scale that couldn’t satisfactorily be reproduced in studio-made construction; we’ve captured a note of realism which also can’t be reproduced in a studio.

Actually, it’s an old idea reborn: back in the days of silent pictures, such location trips were fairly common. But during the past several years we’ve become accustomed to building whatever we wanted in the way of sets, whether it was a small bedroom interior or the exterior of an entire town. Production was much more convenient that way — especially for the sound man, at first, but almost equally so for the director and cinematographer, who found their phases of the work were more completely under control when working within the studio. So, with the exception of Westerns, we had got out of the habit of sending more than a skeleton company on location. It was so much simpler to build even large exteriors on the stage, or to film them as process shots.

But today we can’t build those sets. With a war-time ceiling of $85,000 on new set construction for an entire picture, the building of large sets like these is definitely out for the duration. Yet we still need those sets; so we must go outside the studio and shoot the real thing. In many ways, I’m convinced this is likely to turn out to be an advantage. Technical problems all along the line are likely to be increased, of course, but in exchange, we’ll get a note of realism in both background and camera treatment which is definitely in tune with what audiences want today.

Our Santa Rosa location was chosen because it seemed so typical of the average American small city, and offered, as well, the physical facilities the script demanded. There was a public square, around which much of the city’s life revolves. There was an indefinable blending of small town and city, and of old and new, which made the town a much more typical background of an average American town than anything that could have been deliberately designed. From the technical viewpoint, most of our day exteriors were of a comparatively routine nature. The Santa Rosans were very cooperative, and most of our problems in these scenes were the ordinary ones of rigging scrims and placing reflectors or booster lights where they were needed.

In some of the scenes around the house we had selected to represent the home of our picture’s family, however, we had some problems in contrast. In building a set of that nature we are accustomed to placing trees and the like largely for decorative value. But here they had been planted to provide shade —and they certainly provided it! The troubles we had in controlling the balance between the brightly sunlit areas and the deeply shaded ones left me with unending respect for what America’s amateurs manage to achieve with their Cine-Kodaks under similar circumstances, and without the professional’s opportunity of controlling contrast with scrims, reflectors and boosters!

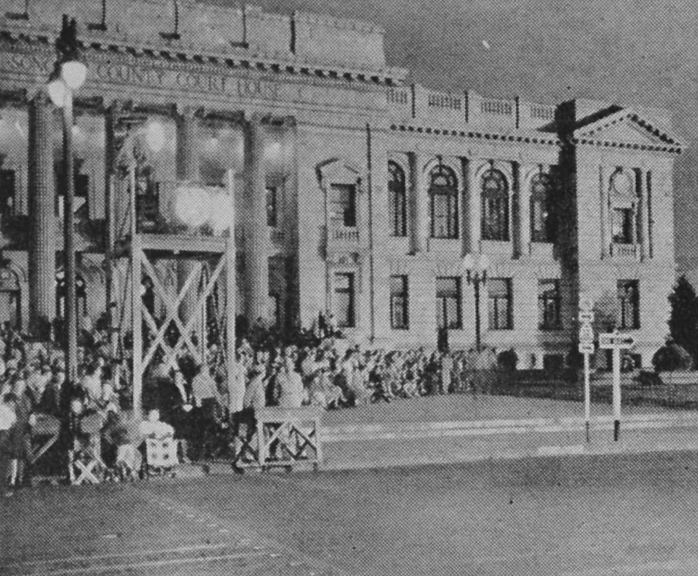

The most spectacular part of our work was naturally the making of the night exterior sequences. We had with us two generator sets, 10 150-ampere arc spotlights, and the usual assortment of incandescent units — Seniors, Juniors, 18s, 24s, and broads — making a total of 3,000-ampere maximum electrical capacity. With this we lit up an expanse of four city blocks for our night-effect long shots!

Most of the credit for this must certainly go to the high sensitivity of the Super-XX negative I used throughout the production. In emergencies like this Super-XX lets a cameraman get the maximum effectiveness out of every light; in this instance, we successfully lit up an area that only a few years ago would have demanded four or five times as much illumination to produce an inferior result. Yet on more routine shots, outdoors or in the studio, the same film gives me a pleasingly normal gradational scale that no other film can equal.

Oddly enough, one of our less spectacular night scenes proved really the harder problem. This was a sequence played around the city’s public library. This building is a lovely Gothic structure, almost completely clothed in ivy. I think all of us were surprised at the way those dark green ivy leaves drank up the light. Actually, on our long shots of that single building we used every unit of lighting equipment we had with us — and we could very conveniently have used more if we had had them!

On some of our other scenes, though, the amazing speed of Super-XX opened up striking pictorial effects to us. There was one night scene, for instance, by the railway station, where with a bare minimum of front light to illuminate the players, a single 150-amp, arc spotlight placed nearly 200' from the camera cast a beam of three-quarter backlight which gave an excellent pictorial effect and a most realistic one.

Lighting up windows on the scale we had to do it in our night-effect long shots was something we could hardly do by the usual studio method of putting a broad or a sky pan behind each window. Here again the speed of Super-XX proved invaluable. We went to Santa Rosa well supplied with Photoflood globes — we must have had about a thousand of them — to use for this purpose. Sometimes we used them in inexpensive “clamp-on” reflectors, but often enough we would simply screw a Photoflood into any convenient socket in the room which was to be lit.

The results on the screen were precisely what we wanted, and by using the Photofloods we could avoid making an additional drain on our rather limited electrical supply, for the Photofloods could be used safely on any home or office lighting circuit.

On several occasions, we made use of a little trick which is rather interesting. In setting up for several of the more intimate night scenes, we found that we could get a better composition and a more natural effect if there were two or three illuminated house windows showing here and there in the background, as from a house in the next block. Only, no house existed in that spot, with or without windows we could light up!

So our crew built up a plywood panel with a row of four window frames in it. This flat could be put in place anywhere that was necessary, and its windows lit up with photofloods. The effect on the screen was quite as convincing as illuminated windows in a real house, even though, as in some of the scenes made around the house used as the home of the principals, the panel was actually placed against a hedge! Of course, we had to be a bit careful not to shoot day effects from the same angle and give away the trick.

By choosing the right time of day for our night-effect shots, we were able to get quite a range of densities in our skies, so that we could suggest twilight, early evening and night very convincingly. Usually night scenes on the screen are played very definitely as night, with inky black skies, and so on. After seeing our rushes on the screen I feel that some of our early-evening effects, with gray yet still luminous skies, and foregrounds suggesting the artificial illumination of just turned on street lights, may perhaps have extended the scope of night effects somewhat.

If we have, I am sure a great deal of credit must go to director Hitchcock for his cooperation in having his cast ready to shoot when the light was right — often at an inconveniently early hour in the evening.

Frequently people who have seen these night scenes of ours have jumped to the conclusion that with such an area to illuminate we must have filmed them by day with Infra-Red film rather than actually by night. If only they’d seen how we worked to finish our night scene before the Pacific Coast’s “dim-out” order went into effect, they’d change their minds. All of our night scenes were filmed actually at night—and we just got under the wire, finishing the last one scarcely a matter of hours before the dim-out became effective.

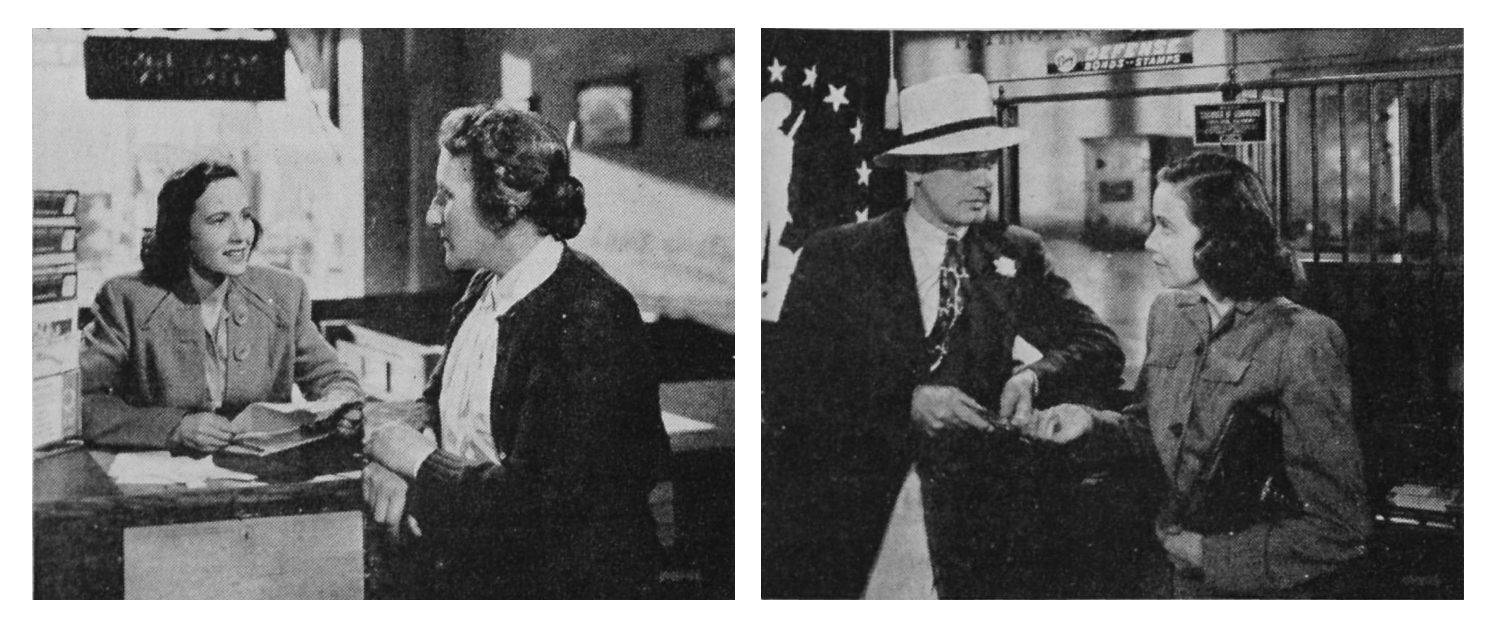

Another very interesting part of the picture was making many of our interiors in actual buildings there in Santa Rosa. For example, we filmed a sequence in the city’s bank, another in the Western Union telegraph office, and another in an actual cocktail lounge.

In the bank and telegraph office, we had the inevitable problem of balancing inside lighting to a sunlit background seen through large windows. This balancing of course was taken care of by placing scrims in the windows and balancing the foreground lighting to the desired level. The result was in every way more natural than if we had tried to duplicate those rooms with studio sets, and of course more economical. Everything in the scene had a note of actuality that is difficult, indeed, to capture in a set.

We made some interiors, too, in the house used for the home of our principals — chiefly scenes in the hallway, in angles shooting toward or through the front door.

In all of these practical interiors filmed up there, we were naturally limited to some extent by the physical limitations of the rooms involved. We had to light entirely from the floor, in much the same way an amateur would in making a 16mm. home movie in the same room. However, we had the advantage of being able to use spotlights, and to position them for cross and backlighting, shielding the lens with goboes.

The results on the screen certainly don’t look like studio-made interiors, but they’ve got an air of naturalness we don’t often get in studio interiors just because everything there can be planned for photography and lighting.

We’ve attempted to reproduce this effect, though, in the other interiors we’ve been making since we returned to the studio. I’ll admit it’s something of a strain, though, trying to keep constantly in mind that our lighting and angles must generally conform to what we could have done in a similar room up there on location!

In this, though, I feel I’m fortunate to be working with so camera-minded a director as Hitchcock. Many a director, under similar circumstances, would take it as evidence of poor cinematography if here there was an almost unbalancedly “hot” light coming through a window, onto actors and back-wall alike, or if there some player had to pass through a shadow which perhaps couldn’t be avoided in real life in such a room, but in the studio could so easily be washed out by bringing in just one more lamp.

But “Hitch” not only understands what we’re attempting photographically but constantly eggs me on, repeatedly asking me, “Are you sure this isn’t too perfect?” or “Are you sure you could have done that in Santa Rosa?”

On his own part, Hitchcock feels that working on actual locations like this, rather than studio-made reproductions, will result in a much more convincingly real picture. “A location like that,” he says, “gives both of us — director and cinematographer alike — much broader scope in painting our picture. In some ways, it was harder for both of us than making the same scenes on studio-made sets, but it paid us back with an atmosphere of actuality that couldn’t be captured any other way.

“Joe got a convincing impression of realness into his scenes which will add immensely to the value of his contribution to the picture. For my part, I had a broader stage to move my actors upon, and I think that the melodrama of the story will be heightened by having such action take place in front of so very real a background.

“People talk about the realistic effects the Russians get by filming so many of their pictures against actual locations, rather than sets, and with everyday people, rather than professional extras, moving through the scenes.

“They do it because they have to. Now that we’re limited as to set-construction, we may find on our part that while we’ve lost something we have considered indispensable, we’ll have gained an element of realism which will more than offset it.”

Italian-American cinematographer Joe Valentine’s other credits include the suspense classics Saboteur and Rope, both directed by Hitchcock. Nominated for four Academy Awards, he won in 1949 for Joan of Arc (shared with ASC members Winton C. Hoch and William V. Skall). He died that same year at the age of just 48.

You’ll learn much more about how Hollywood was changed by the outbreak of World War II here.

Here, Hitchcock discusses his views on cinematography, using recent works as examples, with links to several other archival stories.