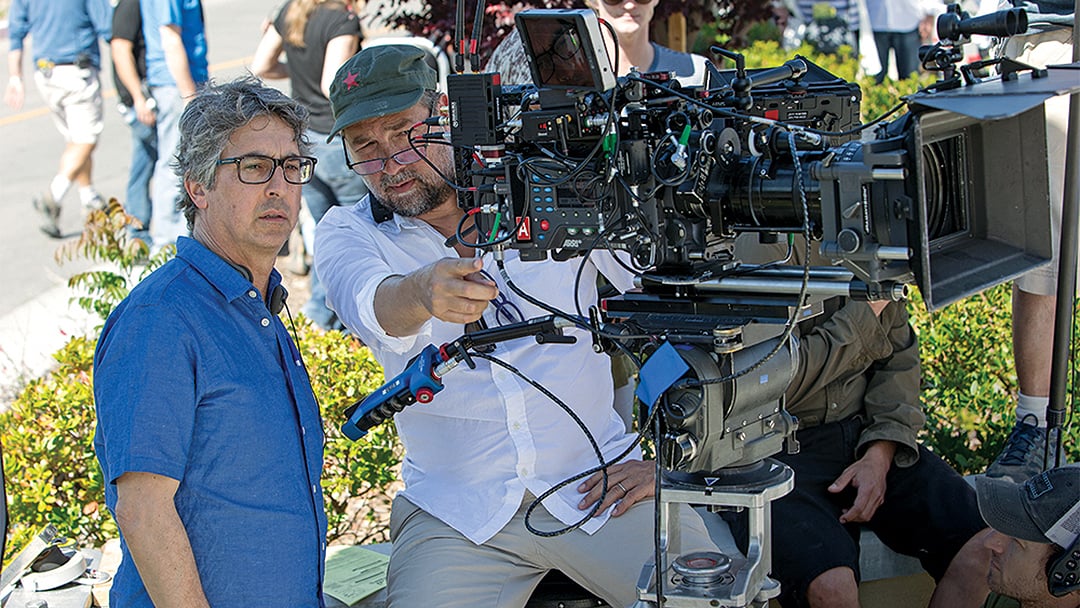

Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC: Downsizing

The filmmaker discusses his latest feature project, the art of collaboration and the importance of using the right cinematography for the story at hand.

Unit photography by Merie Weismiller Wallace, SMPSP, and George Kraychyk, courtesy of Paramount Pictures.

The fourth collaboration between Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC and director Alexander Payne, Downsizing follows everyman Paul Safranek (played by Matt Damon) after he undergoes a procedure that reduces him to five inches in height. It's part of a social experiment to protect resources, limit pollution and ensure the survival of humanity. But Paul discovers that the miniature Utopia he's entered has its own set of problems.

Papamichael previously shot Sideways (2004), The Descendants (2011) and Nebraska (2013) with Payne, earning an Academy Award nomination for the latter.

After a special opening night screening of Downsizing at the Camerimage International Film Festival, Papamichael sat down with American Cinematographer to talk about his work.

American Cinematographer: When did you get involved with Downsizing?

Phedon Papamichael, ASC: Even back with Sideways, which is now 12 or 13 years ago, Alexander and I had talked about two movies he wanted to do. Nebraska was one of them — he called it this little black-and-white film. The other one was an effects film, obviously a harder one to do. He said it cost a lot more money, it was "not the kind of movie I do." He had been trying to make it a long time, so I was aware of it over the years.

It was a difficult film to make because it's a concept film, it's sci-fi, it has a lot of effects, it's a longer shooting schedule. Typically our shooting schedules are a maximum of 50 days. Nebraska was 35, this one was 80.

It's still an Alexander Payne movie, it's just set in a fictitious world of a downsized community. The "big" world and the "little" world were hard for Alexander to wrap his head around at first.

We're filmmakers who are very much inspired by shooting on location. It's almost like a dogma. It operates to the degree that if we see a bar or restaurant that we walk into, Alexander doesn't even want the art work changed. He tries to maintain what he calls the banality of reality. Nothing that seems affected or designed or manipulated. It's very much reality based, it's his impression of what feels is real. When he wants to shoot, he usually casts an actual waitress who works there.

We argue all the time, things like, Would this practical light be on or not? And he goes, "Well, I don't leave my lights on." And I'll say, "But it looks good, and by the way I do leave my lights on." "I always turn them off." So everything has to make sense.

Downsizing was definitely an adjustment for him. James Price, the visual effects supervisor, had to sort of describe to us what things are and where they're going to be. I've done some effects movies, so I kept trying to reassure him that we could just shoot this like a normal Alexander Payne movie, we'll have single camera, and you'll be next to me.

So you didn't have to adjust your approach that much?

Not really. Usually I operate and he sits right next to me. I said we'll bring the actors in and rehearse them and just make up our shots the way we normally do. I didn't feel we should concern ourselves too much with the effects world, just point out what doesn't look right, what looks fake. You don't have to be technical about it.

We shot on location a lot. We started in Los Angeles, we shot about three days in LA where they go to visit Leisureland, which is actually out in the Mojave near Palmdale.

Then we moved to Omaha. That location is very important to him. His characters are usually based in Nebraska, that's where he grew up, that's what he knows, that's the people he knows, the aesthetics he wants to find and portray in his characters. So we shot in Omaha despite its not being a rebate state. It was not easy for the studio to make it happen. We were at the real Omaha Steaks. Paul's high school reunion is actually where Alexander Payne went himself.

Then we went to Toronto and did our stage work, and shot of locations in Toronto. Those bizarre mansions you see when Paul first arrives in Leisureland and drives to his neighborhood, those mini-Versailles replicas lined up — those are all real, even the distances between them. I mean, there are neighborhoods like that.

We took those actual location elements, we collected photo plates and then composited backgrounds to all the foreground action. Very little green screen. The only time we had to get technical is when big people interact with small people.

We had 3D-printed "downsized" people that we could place on a set so the actor could interact with them while delivering lines. It was almost like doing a real scene, but we should shoot the plates of for example the table and then onstage in Toronto weeks later we would shoot that element with him. That's the only thing that was actually technically complicated. Because let's say you have a 4 x 4 bounce source two feet away from a table, all the sources had to be scaled up in order to have the same kind of wrap and fall-off the shadows.

Then it became, well, if the camera's this high, then on stage what would it have to be? It was a lot of math. To shoot in the big world we'd have to be 67 feet high and 100 feet away. That little 4 x 4 bounce that we lit the Cracker Jack box with in the kitchen now has to be three 40 x 40's at 50 feet high.

Determining scale must have been difficult.

Because the light had to be scaled. But that's only the scenes where big and little are interacting. We decided that once we go into the small world, our camera also has shrunk, so we're actually a little camera in that. We're not living in a macro world, so we're not continuously photographing things as if they were small objects. We just shoot it like a regular world, and the lensing is regular.

Every once in a while there's a reminder that we are in that small world, but we didn't want to apply it to everything. Like textiles. Can they actually weave tiny little shirts? You have to remember the downsizing is just a device. Ultimately the movie is Paul Safranek's story; who he is as a person.

Of course there are bigger issues, global warming, immigration, politics, a community living outside this huge wall. All conceived and written before Trump's talk about a wall, by the way.

What's it like working with Payne?

He definitely is very specific. Watching the movie again I saw all the attention he pays to detail. Now that I've seen the film four or five times in a row over a short period of time, I notice something every time. Like, oh, that's why he was so upset that the nurses all wear the same white shoes. Because in reality in the hospital they wouldn't all wear the same style. At the time I was thinking, no, I'm sure it's all right. But now every time that shot comes up, it throws me off also that they all have exactly the same white shoes.

You have to discover that about him. When we did Sideways, at first I thought the shots seemed very basic, but that was his aesthetics. He says, "I just want to tell a story." So someone driving from here to here, we're just going to pan on the car, we're not laying tracks, we're not doing a fancy dolly.

It's really an adjustment because as a cinematographer you're always trying to make shots more dynamic, give them more depth. But the efficiency of Alexander's storytelling, the efficiency of the coverage, is really something I had to discover myself.

Now I think Sideways is a really well-shot movie. Back then I didn't like the look of it so much, not initially. I remember Vilmos Zigmond [ASC, HSC] saying, "No, it's great, it's shot really great, it's perfect for the movie."

I watch it now, a decade later, and think it's really well-shot. But it's subtle. It sort of grows on you. It's like those movies where you find little things and it gets better each time you see them. Like The Big Lebowski.

I just directed a short film, and found myself affected by this approach. Rather than coming up with something complicated, I would do the same thing, I would use the simplicity of the storytelling, just pan with the car and it stops in front of the house and the guy gets out. It really works.

The way we work together, we really don't preconceive so much. We watch movies, we show each other movies that we just like. We'll watch a De Sica comedy, a Hal Ashby movie, a Robert Altman movie, or a Kurosawa film. I couldn't really tell you why, it was just like, look at this.

Our process, it's not specific. We don't shot list, we don't storyboard. We do go on road trips together, less specifically scouting something, just kind of getting bigger impressions of what the feel is. He just wants me to know how people live in Omaha rather than we're scouting this location. And you know we are from the same generation, we grew up on the same movies, we have a cultural connection.

Downsizing looks different from your other films with Payne. It's brighter, sunnier, at times like 1960s sci-fi or educational films.

We kept it low-tech intentionally, in the design as well. Like the whole downsizing sequence, I'm sure you noticed the switches are very primitive, just on and off. There's irony to all of that. The instruction to production designer Stefania Cella was; "Make the downsizing chamber look like a big microwave oven."

When we go to Norway, the water is scaled differently and the flames of the bonfire are different. I kept saying to James do you think people will notice, and he said maybe, maybe not. I just didn't want it to just look weird, like CG.

It terms of my collaboration with Alexander, we shot it the way we shot Nebraska. Single camera, no video village, no playback. The focus puller, the boom guy, me on camera, the director next to the camera, using the same monitor that I actually operate from, and then the actors right there. Creating as small and as intimate a set environment as possible for them.

Alexander said, "I just want to do a movie where I have two people sitting in a cafe talking, and I don't walk around a corner and there's 30 trucks there. I need to get rid of this machinery." So we try to keep it as simple as possible.

There's a scene where dissident Vietnamese refugee and amputee Ngoc Lan Tran (played by Hong Chau) describes what she went through to get to this moment. It's done in one take, a balancing act of performance, directing, and your cinematography.

We knew this was going to be an important performance moment for her. It's also an unusual staging because she's sitting at a table across from three people, Matt, Christoph Waltz and Udo Kier. So we created this very centered single of her. It was a long speech for her, and I knew that she was going to get emotional.

I've learned from working with directors like George Clooney that you often want get the scene in one take. We're usually in the position where if we only had one take, everyone is kind of ready and prepared for that to be the only take in existence.

In this case, I remember I sat sandwiched between Christoph Waltz, Matt and Udo on this bench. I laid a four-foot slider on the table. Say Ngoc is sitting there, I'm with the monitor, and I'm trying to time out this move because it's slow, subtle, throughout her speech. With one hand just pushing the camera into her.

It's kind of a wider lens, it's not the way you would shoot a normal close-up, and I keep her perfectly centered. And she does the scene. I basically extend my arm, get to the end of my slider, and she's done and "cut." I'm crying, Alexander has a tear in his eye, maybe Matt and Christoph also. And we knew that was a great performance.

I do have to say, we did one more. We did two takes, but we used the first one.

There are specific shots for specific moments, but the way we normally approach this is, we see what the actors are doing when we block it, and then we design the shots, the actors leave. Literally it takes us 5, 10 minutes max when we just talk about how we're going to cover the scene.

We kind of just move forward with the coverage and often discover that a shot was very efficient and doesn't require another shot. Sometimes we'll have three shots planned, we'll do the first one and end up eliminating the other two. Say Bruce Dern did something great, I might say that he captured that moment, so we don't need the other shots anymore. Same with Hong Chau. We might have had more shots planned for her, but everyone realized after that shot that we were done.

So it wasn't necessarily planned to be a single take?

We were thinking we would do it tighter, we were probably going to shoot one that was closer throughout, and obviously we didn't do that. We were probably going to do singles on the guys, but in terms of composition, the juxtaposition of the three of them sitting there is much funnier, so we didn't really need singles.

Those are things you discover. You see how a scene plays, what the dynamics are, and the performances. I always like to withhold all those decisions until I actually see whatever the dynamics are on the set.

Even with lighting. Of course you plan and you have the equipment ready, but often I'll say to Alexander, "You know if we do this scene quick, I'm not going to light it. Because right now it's great. I don't need to start setting up Condors and putting up 18Ks out there."

That's what nice about doing small movies. I alternate, so right now I'm doing a very low-budget independent film in the Republic of Georgia called Brighton 4.

I talk to European filmmakers, and they all dream of going to Hollywood. I keep saying, “You guys have a lot of freedom that we don't have. You can be shooting here and the light can be nice over there and you can say let's run over there and grab that. We can't do that, we've got to move base camp, we've got to get all the vans all lined up to transport all the hair and makeup people and move the Porta Pottys and relay cable. It's this ball-and-chain thing, you can't be reactive and free.”

There's usually a moment in Payne's films where it stops being a movie and becomes life. There's a famous shot in Nebraska that does that.

When we drive by Main Street and push in on Peg Nagy [played by Angela McEwan]? Yeah. That shot tells the story, she was his love and she loved him. There are key shots in every movie, some exist specifically in Alexander's head, or we talk about them. That shot was one of them.

Shots like that are more than luck.

It's also about finding and recognizing the moment. It's not predesign, with some exceptions.

Look, great cinematography is being there and finding those moments. You have to recognize them. Alexander would say to Bruce all the time, "Just do your thing and we'll find the stuff." Actors need to feel comfortable and to trust you. They do that pretty quickly with Alexander because they know he's got good instincts.

They'll do things. It's like picking up little gems. I don't think you can really design those. I think that's one of the reasons why Alexander is more like Hal Ashby or Robert Altman. I'd rather be working on his kind of movies, even though I might be getting less attention for visuals. I feel very fortunate to be working with one of the great American auteurs.

You’ll find a complete, detailed production story on the making of Downsizing in the January issue of American Cinematographer.