Outlander: Love Is A Battlefield

Cinematographers Alasdair Walker and Stephen McNutt, ASC, CSC capture the ever-changing eras and locations of Starz’ time-traveling series.

Cinematographers Alasdair Walker and Stephen McNutt, ASC, CSC capture the ever-changing eras and locations of Starz’ time-traveling series.

Unit photography by Aimee Spinks, Mark Mainz, Graeme Hunter and Jason Bell, courtesy of Sony Pictures Television and Starz Entertainment

The camera pans across the blood-covered casualties strewn about Culloden Moor. The Jacobites fighting for a Stuart restoration to the British throne were defeated by government troops in less than an hour on this vicious day: April 16, 1746. A thick fog rolls into the tragic scene. The camera pulls back into a wide shot, revealing the Redcoats searching through the bodies, killing off any traitorous survivors with a stab to the heart from their bayonets. The camera zooms in, searching for and finding Jamie Fraser (Sam Heughan) lying beneath the lifeless body of his mortal enemy, Capt. Jonathan “Black Jack” Randall (Tobias Menzies). As Jamie clings to life, his memory is flooded with images of the ill-fated battle, and through a series of flashbacks, he replays how events unfolded after he sent his wife, Claire Randall Fraser (Caitriona Balfe), and their unborn child back to the future through the ancient stone circle at Craigh na Dun.

Thus, the revelation of what really happened during the Battle of Culloden kicks off Season 3 — also referred to as "Book 3" — of the television drama Outlander, which is based on the novels by Diana Gabaldon.

As time is a flexible element in the Outlander universe, the outcome of the battle was made known back in the pilot episode, with Claire — a former British World War II combat nurse — traveling with her historian husband, Frank Randall, (also portrayed by Menzies) to Scotland in 1945 for a second honeymoon after being separated for years by the war. They tour the ruins in and around the city of Inverness, including the Culloden battlefield, and revisit the battle’s tragic narrative — a trip that, at the time, seems simply to be an opportunity for Frank to learn a bit more about his family history.

The day after witnessing a Druid ritual at Craigh na Dun, Claire accidentally travels through one of the standing stones and plunges into the turmoil of 1743 Scotland. Forced to marry Jamie as a means to escape the clutches of Frank’s villainous ancestor, Claire finds herself falling in love with her new husband, and reveals to him her time-traveling secret as well as the true outcome of the Jacobite rebellion and the end of Highland clan culture.

Wondering if perhaps they can change the future, Jamie and Claire — accompanied by Murtagh Fitzgibbons (Duncan Lacroix) — travel to Paris in Season 2, in hopes of foiling the war efforts and saving the lives of thousands. Despite their efforts, it becomes clear that the future is set in stone. A now-pregnant Claire travels back through the stones to 1948, returning to Frank, and spends 20 years thinking that Jamie died in battle. However, on a trip to Scotland in 1968 with her daughter, Brianna (Sophie Skelton), to attend the funeral of Reverend Wakefield (James Fleet), Claire discovers the truth: Jamie survived Culloden.

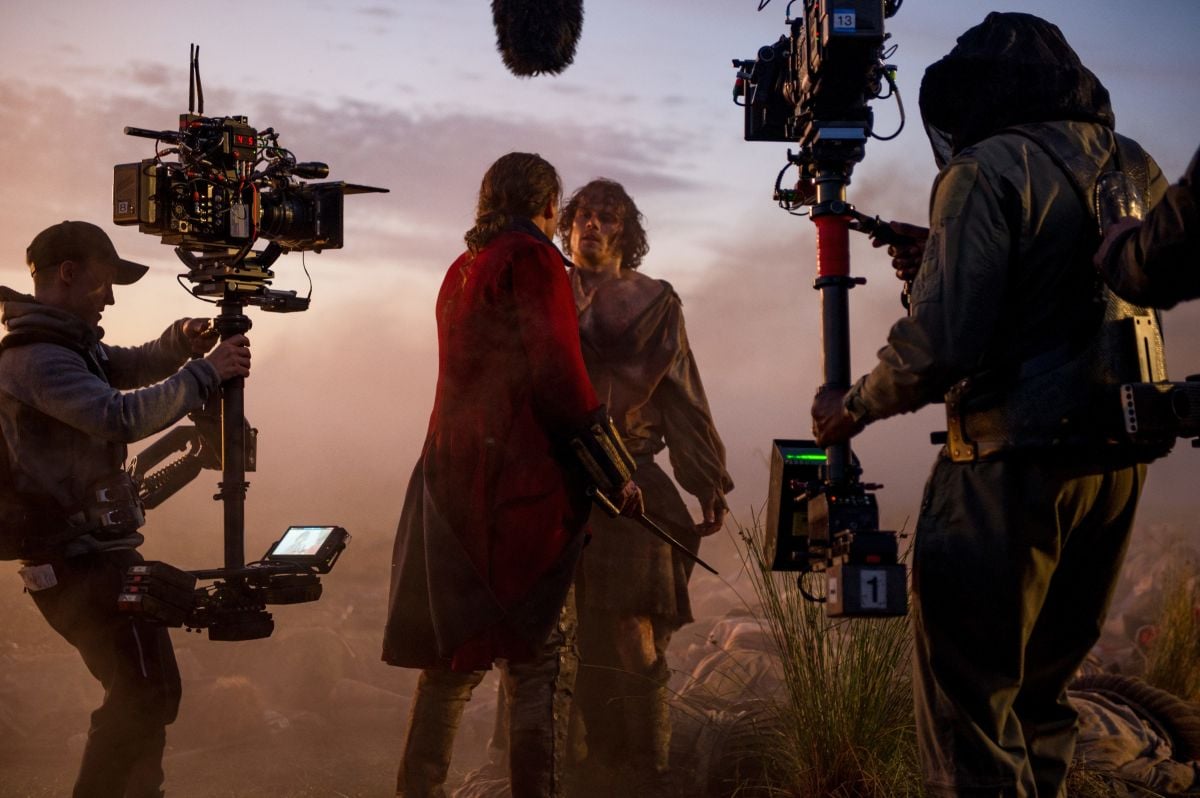

“Season 3 begins with the main battle sequence in the Outlander series, and the final encounter between the hero Jamie and the villain Captain Jack Randall,” explains cinematographer Alasdair Walker. “Director Brendan Maher and I, along with the writers, wanted to approach the battle sequence in a way that was different from what is shown on other shows, like Game of Thrones. We wanted an extensive sequence that is part dream sequence and part action sequence, so we worked it out as a series of flashbacks.”

Committed to an authentic portrayal of the battle, the production performed extensive research with assistance from the University of Glasgow archaeology department. It is known that with their broadswords in hand, the Highlanders charged the government regiments, a tactic that had worked to their advantage in previous encounters. To capture this suicidal charge into cannon and musket fire, Walker employed multiple cameras — predominantly Sony PMW-F55 CineAltas, the production’s primary units, fitted with Cooke S4 Primes and Arri/Fujinon Alura 18-80mm and 45-250mm zooms (both T2.6) — shooting in 2K and 4K simultaneously, and recording to SxS Pro+ memory cards and Sony AXS-R5 external 4K raw recorders, for each respective resolution. Multiple handheld and Steadicam rigs, as well as tracking vehicles fitted with Technocranes, also serviced the sequence.

Supplementing the F55s were Sony a7S cameras — fitted with Sony FE 16-35mm GM (F2.8) zooms and shooting 4K to SanDisk Extreme Pro SD cards — that were buried in armored boxes, enabling the Highlanders to trample over them during the action, as well as GoPro Hero4s, which were mounted to the soldiers’ shields.

The real-life battle took place in late winter, with sleet and snow falling during the bloodshed, while the event’s onscreen re-creation was shot in mid-August with an unusual amount of sunny weather. To simulate the cold, overcast feel for the start of the battle, the special-effects department added large amounts of smoke to create a foggy atmosphere that also diffused the sunlight.

For the key sequence at the end of the battle between Jamie and Jack, Walker notes that he decided to create a look that was “quite a departure from what had been shot just previously.” With executive producer Ronald D. Moore’s approval, Walker, the special-effects department and the crew created a sunset “red flame” look. In the background, the Redcoats set fire to the heather, bringing dark smoke into the scene. The fast cutting featured throughout the bulk of the battle slows down as the characters tire and the flames become more prominent. With restrictions on which materials could be burned, “paper cannons” were employed to shoot black particles in the air for added realism.

“We shot the scene at sunset and we really did have an amazing sunset in the sky that evening,” Walker says. He reports that as the real sun sank further into the horizon, “18K Arrimaxes, color-corrected to tungsten and warmed further with CTS,” were gradually added for a seamless transfer between light sources. “We also used Maxi-Brute Nine Lites with a fire-flicker effect at ground level to simulate heather fires,” Walker adds. The combination of sunset and fire effects resulted in a scene that Walker describes as something out of a J.M.W. Turner painting.

When the battle flashbacks end, night and snow fall upon the battlefield. In a dreamlike state, Jamie imagines Claire walking through the field, searching for him in the moonlight. “[Gaffer] Scott Napier asked Ross Pearson, the rigger, to build a truss cage into which two 18-foot-by-8-foot SourceMaker balloons were fitted,” Walker says. “They each contained four 4K MSR lamps.” The cage was mounted to “an 80-ton construction crane,” he reports, to create the soft moonlight effect. “Arri S60 SkyPanels were used to provide a harder moonlight rim,” Walker adds.

Meanwhile, as it were, the narrative shifts to Claire’s point-of-view in 1948 as she arrives in Boston with Frank, who has taken a position at Harvard University. After three years in the 18th century, Claire finds it challenging to re-acclimate to modern times. According to production designer Jon Gary Steele, the challenge for the crew was not unlike Claire’s, in that they are constantly on the move and shifting gears as they handle different time periods.

Steele recounts how a scenic-artist friend had once told him about a director who had requested that all the colors in the film they were working on should be the popular car colors of that era. Inspired by this, Steele had the Outlander art department develop a car-color sample book from the 1950s and ’60s — and then sat down with supervising art director Nicki McCallum, set decorators Gina Cromwell and Stuart Bryce, and head scenic artist Bettina Scheibe to pick the colors for Boston, which the team ultimately decided would be various shades of blue and green.

Walker adds that he and Steele attended a Kodachrome photography exhibit by William Eggleston. Admiring his work prompted them to introduce progressive additions of color as the years went on, resulting in the 1940s being more washed out in comparison to 1968s Kodachrome feel, with its stronger reds and blues.

The Boston scenes were shot on the Wardpark Film and Television Studios, Scotland’s only fully integrated production studio, located in Cumbernauld, North Lanarkshire.

“We don’t have any permanent sets,” says Steele. “A lot of our sets are changed and reworked — whole new sections will be added with new fireplaces, stairs and windows, thus creating a whole new look. When we shoot at historical locations that are hundreds of years old, they do not want fires in the fireplaces or sconces with flames on the walls, so we build and film most of the interiors on our soundstages.”

The stage is equipped with a Chamsys MQ200 lighting console, operated by Jon Towler, which controls an extensive array that includes Arri SkyPanel S30s and S60s with honeycombs, Chimera lightbanks with frames and DOPChoice SnapGrids, and on-set practicals. Walker reports that he and Napier recently used the cinematographer’s trusted Sekonic Spectromaster color meter to test out the color-rendering index values on each of the studio’s LED lights to ensure the gels maintain strong CRI values.

“A good amount of red in the CRI is needed to maintain skin tones on stage,” says Walker. “For interior night scenes, I’ve started using Kino Flo Select 20 and 30 LED [fixtures] that, even when dimmed down, produce a light that is true. We also tend to use curved depron and various frames to create a soft light that is really good for skin tones.”

Walker further mentions that a pattern was developed with the aid of the lighting console to create realistic flame effects that were emitted via flicker boxes, for interior scenes shot on the soundstages.

Cinematographer Stephen McNutt, ASC, CSC also emphasizes the importance of firelight on Outlander. “In the 1700s, there were three main lighting sources: sunlight, moonlight and firelight,” he says. “For interior scenes, I decided to make firelight the most important part of the illumination, with daylight and moonlight coming through the windows as a secondary light source.”

Napier explains that both McNutt and Walker employed “flicker pads/packs that were designed and built by myself and my team using LiteGear tape, [with] wireless DMX LED dimmers from Panalux and Theatre Wireless to control them through the lighting desk.”

McNutt adds, “We also used the amazing Arri LED SkyPanels. All lights were DMX-connected to our board, where our board operator, the ‘infamous’ Jon Towler, was able to control the color, intensity and flicker, as per my instructions. The light packs were also battery operated when mobility was needed.

“I did the reverse in the 1940s,” he continues, “using daylight as the main lighting source and making firelight a metaphor for the past.” An example of this is evidenced in the “Through a Glass, Darkly” episode in Season 2, which is set right after Claire returns to the 1940s. Claire and Frank are staying in separate rooms in the home of Reverend Wakefield in Inverness, during her convalescence after a hospitalization. Late in the evening, Frank walks up a darkened stairway, pauses in front of Claire’s door, and — seeing no illumination — turns toward his own room. Claire opens her door and calls his name. She steps into the doorway, half in shadow and half in the warm firelight emanating from her bedroom. Frank steps toward her, becoming fully illuminated. She invites him inside, they sit in front of the fireplace, and Frank brings up the memory of the last time they sat together in front of a fire. In the morning, Frank throws one last log on the dying embers, as daylight and the present reality stream into the room.

“In the bedroom scene when Claire and Frank talk in front of the fireplace, I used the same LED packs as [those employed] in old Scotland,” McNutt says. “The daylight was [provided by] basic HMI lights from a lift. I used the same packs in daylight settings for a soft key or fill. The hope was to draw a separation between the [time periods]. For the Forties, the colors were saturated differently with fire, and I was going for more of the hand-painted pastel feel. Night scenes were lit by incandescents, and fire took second place unless it was in direct connection to the past.”

In a scene shot by Walker, which appears in Episode 1 of Season 3 — “The Battle Joined” — a pregnant Claire is at their new home in Boston, trying to readjust to modern conveniences like a gas stove. Frustrated with her inability to light the burner, Claire turns to the methods of the 18th century and cooks her meal in the fireplace. The light from the fireplace, Walker explains, was derived from “a combination of real flame special effects and the multi-channel LED lighting pads [which were] wirelessly linked to the desk controlled by Jon Towler. The pads contained tungsten LiteGear LED tape laid in strips.”

Each season of Outlander — a show whose cinematographers have also included David Higgs, BSC; Denis Crossan, BSC; Michael Swan, SASC; Martin Fuhrer, BSC; and Neville Kidd — not only marks a new era for Claire and Jamie, but also new locations, such as Claire, Jamie and Murtagh’s trip to Paris. As the French city’s aesthetics have changed significantly since the 18th century, production shot the Paris-based scenes in historically preserved locations, such as Prague Castle, as well as areas throughout Scotland and England. McNutt tested several cameras for those scenes, and opted for Arri’s Alexa Plus, as it was determined to properly reproduce the colors of Steele’s sets, as well as the hues of the elaborate costumes designed by Terry Dresbach.

“Our primes [for the Alexas] were Cooke S4s, and the zooms were the [Arri/Fujinon] Alura 15.5-45mm [T2.8], 18-80mm and 45-250mm,” McNutt says. “We tested a number of cameras and decided that the Alexa was the most accurate in [terms of] the delicate color rendition that was necessary to record the amazing costumes, sets and locations that made up Paris. We shot 3.2K with the Arri, and went to 4K when we returned to Scotland and converted [back] to the Sony F55.”

The ball held by King Louis XV (Lionel Lingelser) at the Palace of Versailles was shot at the historic Wilton House in Salisbury, England. “The Wilton House is an amazing palace that was used in Barry Lyndon,” McNutt relates. “We used a combination of Steadicam and cranes to give us the flexibility to show off the beauty and magnitude of the world in which they lived. Steadicam operators Andrei Austin and Ossie McLean really pulled out all the stops.” There were strict rules prohibiting the placement of anything on or near the walls, though McNutt reports that the production was “allowed to use candles on floor-standing candelabras.”

At McNutt’s request, Napier created an aluminum tube wrapped in LED lights that he fitted into China balls, which were used for fill and strung near the chandeliers, as well as inside balloons placed throughout the ballroom. “I used a large balloon in the center of the ballroom, skirting it with black, and then a lower bobbinet skirt to make the shadow on the wall more gradual,” McNutt says. “Smaller balloons were used in other rooms, but when possible I preferred to light from the floor or the fireplaces. I used a Menace Arm to lift instruments when I needed to work within a crowd. It’s quite a challenge to give the room shape when your control is so limited. The crew is outstanding and I think we did rather well.

“The blue LED China balls that I designed with Scott Napier were used for cool fill against the warmth of the firelight, and also to provide sheens on walls and paintings in the background,” he continues. “In most locations we were able to hang the China ball on a string suspended between the chandeliers. The weight was so small that it was approved. It did create problems at times [in terms of] seeing the ceilings, but we planned the shots in advance and were able to remove the necessary sources to get the job done.”

For the fireworks display at the end of the ball, the actors gathered around the windows, looking toward greenscreens placed by the visual-effects team. Through his lighting console, Towler synced a light bar with the corresponding lights and colors of the visual-effects fireworks so that every time a firework went off, the room filled with the appropriate light and color.

One of McNutt’s favorite locations for Season 2 was the Glasgow Cathedral, which was used for the interior scenes of L’Hôpital des Anges, where Claire — feeling neglected by Jamie — begins volunteering. “In the cathedral, we needed to tent the entire south side to control the sun,” McNutt relates. “It was a massive undertaking and [the crew did] an outstanding job. We [shot with] a combination of Steadicam, dolly and crane; they were scenes of elegance and power.”

McNutt enjoyed the natural textures and tones of the interior, but was restricted from creating additional atmosphere to enhance the feel of the location. They were permitted to use candles, however, and after every take, two crewmembers — George Booth and Bill Gower — from standby-props were responsible for blowing out all the candles and relighting them, in order to maintain continuity. As it turned out, the resulting smoke from the candles hung in the air and created the additional atmosphere McNutt was after.

“Bill and George worked diligently throughout production,” McNutt says. “Amazing guys and always smiling. They always called me ‘Stevie.’”

For a prison scene in Episode 3 of Season 3, “All Debts Paid,” shot at Craigmillar Castle just outside Edinburgh, the production encountered a challenge similar to that of the Wilton House, wherein the walls were not to be touched — but this time the filmmakers were capturing exterior scenes that required an overcast look. Walker, Napier and Pearson were thus tasked with devising a method for stopping the sunlight from directly entering the courtyard. The solution was to suspend wires counterweighted with water ballasts, allowing 40'x20' silks and solids to fly at any angle without touching the stonework.

The Season 3 shoot relocated to South Africa to capture “the sea journey to the Caribbean, particularly Jamaica and Saint-Domingue,” Walker explains. For this segment, the crew switched from F55 cameras to Red Epic Dragons, which recorded Redcode Raw — at “5K, downscaled to 4K, allowing a ‘look around’ in the viewfinders and monitors,” he says — to 512GB Red Mini-Mags at a 6:1 compression ratio. “We made the switch because we wanted to utilize the HDRX built into the Red system,” Walker notes. The Red cameras were paired with Panavision Primo Primes and Zooms.

Throughout shooting, the cinematographers are in constant communication with co-producer Elicia Bessette and MTI colorist Steve Porter. Walker notes that he, Bessette and Porter communicate via Skype sessions, during which they review the episodes on calibrated monitors. Porter performs the grade with Digital Vision’s Nucoda.

“In Scotland at the studio, we [worked] with post supervisor David Frew and dailies supervisor Ben McKinstrie,” McNutt adds.

McNutt, Steele and Walker agree that Outlander works because of the production’s strong collaborative efforts. “The direct communication involved creates a very supportive environment,” Walker says. “Everyone is very willing to communicate and let you know if you are moving in the right direction or not. There is no ambiguity. The support and input from executive producer/writer Matthew B. Roberts and producer David Brown throughout Season 3 was invaluable to the production.”

“The cast and crew are amazing,” adds McNutt. “They are incredibly hard-working, wonderful people who don’t mess around. With production in Scotland set as a 10-hour workday, the crew stays focused, knowing what time they are going home each day. It makes a huge difference on a psychological level and creates a safe and productive set. Outlander was one of the best experiences of my life. I will always be grateful to my friend Ron Moore for asking me along on this adventure.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

| Aspect Ratio | 1.78:1 |

| Stock | Digital Capture |

| Cameras | Sony CineAlta PMW-F55 |

| Sony a7S | |

| GoPro Hero4 | |

| Arri Alexa Plus | |

| Red Epic Dragon | |

| Lenses | Cooke S4 |

| Arri/Fujinon Alura | |

| Sony G Master | |

| Panavision Primo Primes and Zooms |