NYFF Curators Discuss Picks for ASC Retrospective

New York Film Festival’s Kent Jones and Dan Sullivan explain some of the decisions that went into selecting the 13 features included in this series for their outstanding cinematography.

New York Film Festival’s Kent Jones and Dan Sullivan explain some of the decisions that went into selecting the 13 features included in this series for their outstanding cinematography.

The 57th annual New York Film Festival ended October 13 after screening 29 features in its “Main Slate” selections. The fest also highlighted documentaries, shorts, and series devoted to innovative and immersive filmmaking. Two series explored revivals and restorations, including new versions of key Luis Buñuel films, Béla Tarr's seven-hour epic Sátántangó, and William Wyler's Dodsworth.

The screening showcase “Retrospective: The ASC at 100” — honoring the Society’s 1919-2019 centennial — featured 13 titles curated by director and chair of the NYFF Selection Committee Kent Jones and assistant programmer Dan Sullivan. Ranging from Frank Borzage's 1928 silent drama Street Angel (cinematography by ASC members Ernest Palmer and Paul Ivano) to Dave Chapelle's Block Party (2005, cinematography by Ellen Kuras, ASC), the retrospective included landmarks like Days of Heaven (1978, cinematography by Néstor Almendros, ASC and Haskell Wexler, ASC), The Godfather: Part II (1974, cinematography by Gordon Willis, ASC), and the film noir He Walked by Night (1948, cinematography by John Alton).

Here Jones and Sullivan discuss some of the decisions that went into selecting the 13 features included in this series.

American Cinematographer: How did the series come about?

Kent Jones: This started when Denis Lenoir [ASC] reminded me that this is the hundredth anniversary of the ASC. We thought it would be great to show a selection of films from throughout the history of the organization that reflected both the peaks and the changes in the craft of cinematography.

Dan Sullivan: We concluded pretty early on that it wouldn't be possible to do an exhaustive, historical overview of the ASC. The list we came up with hopefully captures a breadth of cinematographic development over the past hundred years. We were also thinking about how the retrospective in the NYFF functions from year to year. As viewers we watch new films and old films together, we don't focus solely on one or the other. So we were thinking about the purpose of the retrospective in the context of otherwise contemporary films.

A number of the titles fall into or near the film noir genre. Diao Yinan, director of The Wild Goose Lake, which screened in the Main Slate, cited some of the retrospective's titles as influences on his work.

DS: We didn't consciously focus on film noir, but then again film noir is one of the great American contributions to cinema so far. The genre was extremely important in the development of lighting techniques in Hollywood. John Alton's work on He Walked by Night is immense. What he was doing with light, and the absence of light, is comparable to anything the German Expressionists achieved.

KJ: It's rare that you have a film where the cinematographer unifies the work. Alfred Werker is the nominal director of He Walked by Night, and you can feel his presence in the movie. But because of the material, its extreme docudrama nature, it's really Alton that unifies the movie.

Can you explain some of your choices? Why America, America for Haskell Wexler instead of his perhaps more famous titles like Bound for Glory?

DS: We did a series a few years ago for the anniversary of the Steadicam and showed Bound for Glory in that. That's true for a number of the cinematographers here, we've recently shown some of their more familiar work. So we wanted to make surprising or interesting choices, films our audience hasn't seen in a while. Deep cuts.

KJ: America, America has the feel of a hand-made epic. It's about [director Elia] Kazan's uncle, there's a glimpse of him in Boomerang, craning his head around the corner after the gunshot. It's a unique collaboration from early in Wexler's career. He and Kazan did not see eye-to-eye politically. They may not have gotten along as people, but they did have a lot of respect for each other as artists. Wexler was able to bring that eye, one trained in documentary, that had a sensitivity to light and shadow, to the project. It puts me in the mind of Robert Frank.

How important is it to see films like these projected on the big screen?

DS: All these films were made to be seen big, ergo they were shot to be seen big. A film like Days of Heaven, you could make the argument that you haven't seen it until you see it in a theater to appreciate the majesty of Almendros's work there. My attitude about home viewing in general is that it's fine but it's not an adequate substitute for seeing a film in a theater. People wouldn't see a postcard of a van Gogh and say that they've seen the painting. They may know what it looks like, but it's not the same as seeing the real thing.

KJ: Maybe if you're making web episodes, then you're not thinking of the big screen. But for the most part most filmmakers are thinking of their films being on the big screen. That was the only way to see them before television.

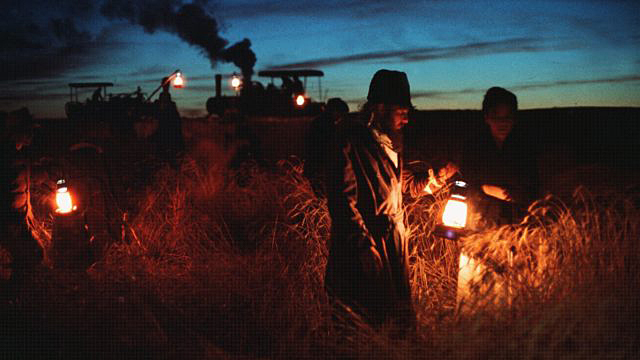

It's hard to grasp the visual splendor of Days of Heaven on a TV screen or iPhone.

KJ: I remember seeing that film on its opening weekend on an enormous screen up in Montreal. When it came out, it felt like nothing else. You just experienced it — you had to take it in four or five times to get the full feel of what he was doing.

As Almendros pointed out in his book, he's shooting with natural light. Something he always had an issue with when people are outdoors by a campfire in movies, inevitably there was artificial lighting somewhere that betrayed itself in the look of the movie. In Days of Heaven the firelight scenes are really lit by fire. He's really lighting people with firelight, propane gas torches, things like that.

The series includes several European cinematographers: Almendros, Sven Nykvist, Vilmos Zsigmond — also ASC members — and Robby Müller.

KJ: These selections are just a drop in the bucket. I could give you a long list of people who were not included because we only had so many movies we could show. The fact that Zsigmond is represented and László Kovács [ASC] isn't — they're both artists of enormous stature. What's interesting about Nykvist is the bond he formed with director Ingmar Bergman. This was a phenomenon of post-studio-era filmmaking, where you get these relationships between directors and DPs. The bond between Sven Nykvist and Ingmar Bergman stands out as one of the great creative partnerships in movies. They worked out an approach to the movement of the camera that was sculptural and hypnotic at the same time, so that you have the sense of the camera moving but also the world moving around the camera. It's uncanny. Vilmos Zsigmond developed that kind of a relationship with different filmmakers, like the work he did with Robert Altman. So did Gordon Willis [ASC]. He had one kind of relationship with [Francis Ford] Coppola, another with Alan Pakula, another with Woody Allen. Marty Scorsese had different kinds of relationships with DPs, specifically Michael Ballhaus [ASC], and Michael Chapman [ASC], too, and now Rodrigo Prieto [ASC]. I had a conversation with a filmmaker who asked Gordon Willis why Godfather 3 looks less exciting than parts one or two. His answer was, "That's easy, the film stocks got smoother and more predictable." We're showing an IB print of The Godfather: Part II. It's not in the best shape, but the point is the color. You can sit through the splices just to experience the extraordinary look of the film. It was the last Technicolor film released in the IB process [in the US].

You're showing a new restoration of Soldier Girls, shot by Joan Churchill [ASC]. She also co-directed with Nick Broomfield.

DS: She's an extremely important figure in documentary. The relationship between cinematographer and subject becomes really complicated in her work. One of the contributions she and Broomfield make to the field is to examine that relationship between filmmaker and subject.

KJ: Joan's an amazing cameraperson, and because of the time limitations of our series she has to stand in for a whole range of filmmakers like Al Maysles, DA Pennebaker, Robert Frank. You need to bring something very particular when you're shooting that way, a responsiveness and alertness and attention. It's almost like you're bonded with your subject, you're responding immediately to everything that's going on in your vicinity. The responsive eye is something that really characterizes Joan's work.

Here are the NYFF listings on the films that screened in the “Retrospective: The ASC at 100” series:

America, America (1963)

Director: Elia Kazan

Cinematography by Haskell Wexler, ASC

Haskell Wexler’s sumptuous and kinetic black-and-white handheld cinematography suffuses America, America with a spontaneous energy, greatly enhancing Elia Kazan’s turn-of-the-20th-century portrayal of an immigrant’s journey to a better life.

Dave Chapelle’s Block Party (2005)

Director: Michel Gondry

Cinematography by Ellen Kuras, ASC

Michel Gondry’s 2005 documentary of a free daylong performance in Brooklyn hosted by comedian Dave Chapelle abounds with life, energy, and rhythm—thanks in no small part to DP Ellen Kuras’s nimble camera, which captures the all-star concert as a kaleidoscopic, reverberant event.

Days of Heaven (1978)

Director: Terrence Malick

Cinematography by Néstor Almendros, ASC & Haskell Wexler, ASC

Néstor Almendros’s first Hollywood film was Terrence Malick’s anticipated follow-up to his debut, Badlands. Hired by Malick for his sure hand with natural lighting, Almendros ravishingly draws out and amplifies the inherent beauty and poetry of Malick’s 1916-set story.

Dead Man (1995)

Director: Jim Jarmusch

Cinematography by Robby Müller, NSC, BVK

Jim Jarmusch’s hypnotic, parable-like, revisionist Western doubles as a barbed reflection on America’s treatment of its indigenous people and a radical twist on the myths of the American West, expressed in no small part by Robby Müller’s striking black-and-white cinematography.

The Godfather: Part II (1974)

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Cinematography by Gordon Willis, ASC

Francis Ford Coppola and Gordon Willis enjoyed one of the 1970s’ most defining cinematographic partnerships, and their most astonishing collaboration was the second installment of Coppola’s adaptation of Mario Puzo’s best-selling novel, lent unsurpassed dimension and atmosphere by Willis’s masterful compositions and lighting.

The Grapes of Wrath (1940)

Director: John Ford

Cinematography by Gregg Toland, ASC

Though Gregg Toland is perhaps best known for his work on such films as Citizen Kane and The Best Years of Our Lives, his camerawork in John Ford’s adaptation of John Steinbeck’s classic novel rates among the influential cinematographer’s greatest achievements.

The Hard Way (1943)

Director: Vincent Sherman

Cinematography by James Wong Howe, ASC

The pioneering Chinese-American cinematographer James Wong Howe shot more than 130 films during his distinguished career—perhaps none as engrossing and entertaining as Vincent Sherman’s 1943 genre-melding musical melodrama.

He Walked by Night (1948)

Director: Alfred L. Werker

Cinematography by John Alton

Alfred Werker’s pseudo-documentary noir, a lean, mean thriller concerning a petty thief (Richard Basehart) who kills a cop and roams Los Angeles, represents one of cinematographer John Alton’s crowning achievements, an endless, anxious maze of urban shadows.

Leave Her to Heaven (1945)

Director: John M. Stahl

Cinematography by Leon Shamroy, ASC

Leon Shamroy’s Oscar-winning work on Leave Her to Heaven marks a historically inspired attempt at a kind-of squaring of the circle: shooting a gripping noir—with Gene Tierney as a murderously selfish femme fatale—in vibrantly beautiful Technicolor.

The Passion of Anna (1969)

Director: Ingmar Bergman

Cinematography by Sven Nykvist, ASC

Filmed by Sven Nykvist on Fårö, Ingmar Bergman’s bleak island home, The Passion of Anna is the case history of a contemporary Everyman, one Andreas Winkelmann (Max von Sydow), a lost soul ricocheting emotionally among a trio of equally damaged folk.

Soldier Girls (1981)

Directors: Nick Broomfield, Joan Churchill, ASC

Cinematography by Joan Churchill

Following a platoon of female cadets through basic training at Georgia’s Fort Gordon, Nick Broomfield and Joan Churchill’s 1981 documentary endures as a comical and often critical look at the military industrial complex. Churchill’s dual role as cinematographer and director intensifies her already complicated relationship to the subject.

Street Angel (1928)

Director: Frank Borzage

Cinematography by Ernest S. Palmer, ASC and Paul Ivano, ASC

Brilliantly shot by Ernest Palmer and Paul Ivano, Street Angel has endured as one of Borzage’s most transporting and affecting weepies, about a young woman (Janet Gaynor in an Oscar-winning role) forced into a life of crime by her ailing mother’s escalating medical costs.

Acknowledgments: Denis Lenoir, ASC; Department of Communication Arts at the University of Wisconsin-Madison; UCLA Film & Television Archive

Jones recently stepped down from his position at the NYFF. He will continue to work with Film at Lincoln Center in an advisory role. He has worked with FLC since 1998.