“Natural” Lighting For Interior Sets

Arthur C. Miller, ASC discusses his lighting approach to five different scenes, detailing each with diagrams.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in AC, March 1940 and AC September 1966.

With the advent of smaller lighting units, higher exposure indexes and digital photography, miniature lighting units have become the fine brushes by which the cinematographer can paint precise light effects with the small delicate brushstrokes that have been long needed. For practical illustrations of some of the methods of using these small lighting units for precision lighting I have turned to specific scenes I have photographed.

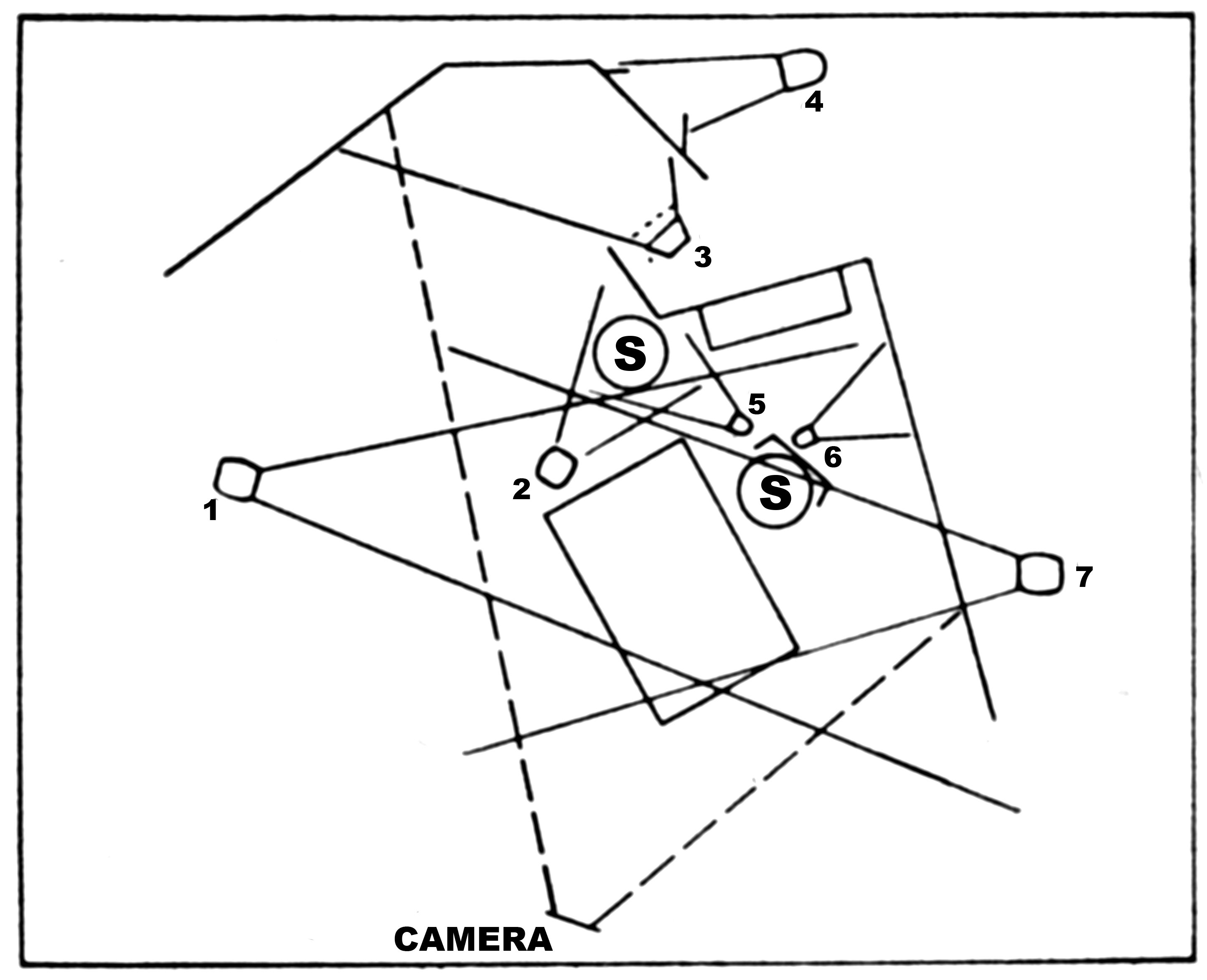

Figure A. In lighting this scene there were three paramount considerations. First, we had to make it logical that the face of pseudo monk should remain darkly invisible to the heroine, yet at the same time, when the monk turns during a later phase of action, his face must be visible to the audience. Second, the heroine must be lighted as to present her beauty attractively. Third, the set had to be lit in such a way as to be compositionally attractive, and to make the lighting on the two people believable.

The accompanying diagram shows how this scene was lighted using three 500-Watt Baby Keglights and six 150-watt Dinky Inkies. Baby key #1 provided the key light. It not only illuminated the heroine, but also provided a logical reason for keeping the monk’s face heavily shadowed beneath his cowl. Baby key #7, placed high on the lamp deck, provided the necessary backlighting on the heroine and on the railing behind her, to separate them from the background. Baby key #6 also on the overhead lamp deck, provided additional top-backlight on the set and players from this necessarily important angle.

Dinky Inkies #s 2 and 3 were concealed behind the flowers on the altar in the background, and were directed upward along the wall. It will be noticed that their beams fall in front of the candlesticks at the altar, throwing their shadows against the wall — a logical and necessary effect, since these candles were not lighted. On the other hand, Dinky Inkies #s 4 and 5, which were concealed behind the flowers at the smaller altar, cast their flooded and diffused beams on the wall behind the candlesticks and on the statue. This again is logical, for these beams simulate the natural, visual effect of the light from these lighted candles. These small lamps, which can be concealed so easily within the scene, permit us to get away from the unnatural method of creating such lighted-lamp effects by means of a concentrated beam from a spotlight on the opposite lamp deck, which inevitably defeats its purpose by also casting on the back wall the shadow of the light fixture which is supposed to be producing the illumination! Dinky Inky #8 performs a similar service for the candles before the figure directly behind the heroine, while Dinky Inky #9 completes the lighting by providing a soft “filler light” in that corner of the set.

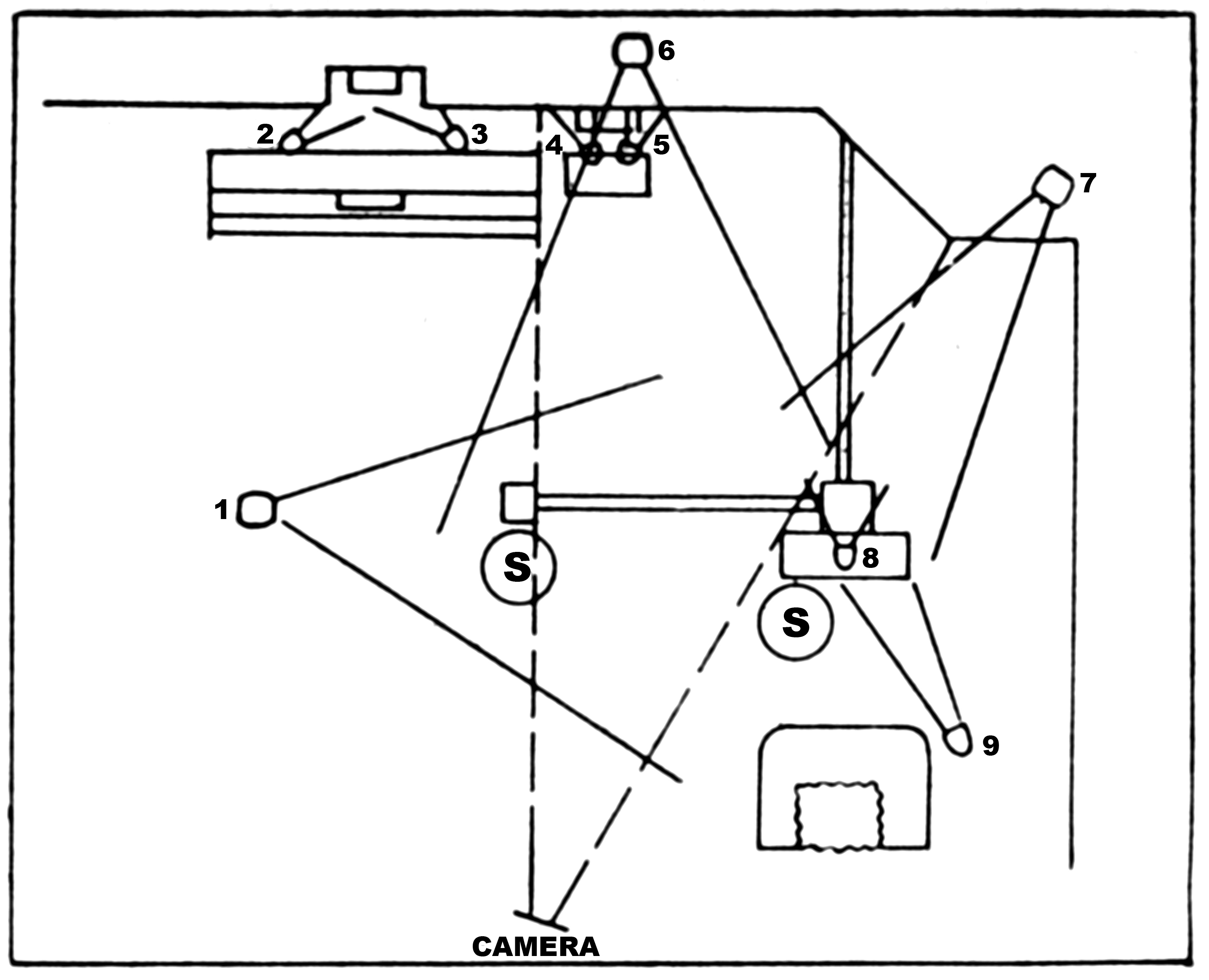

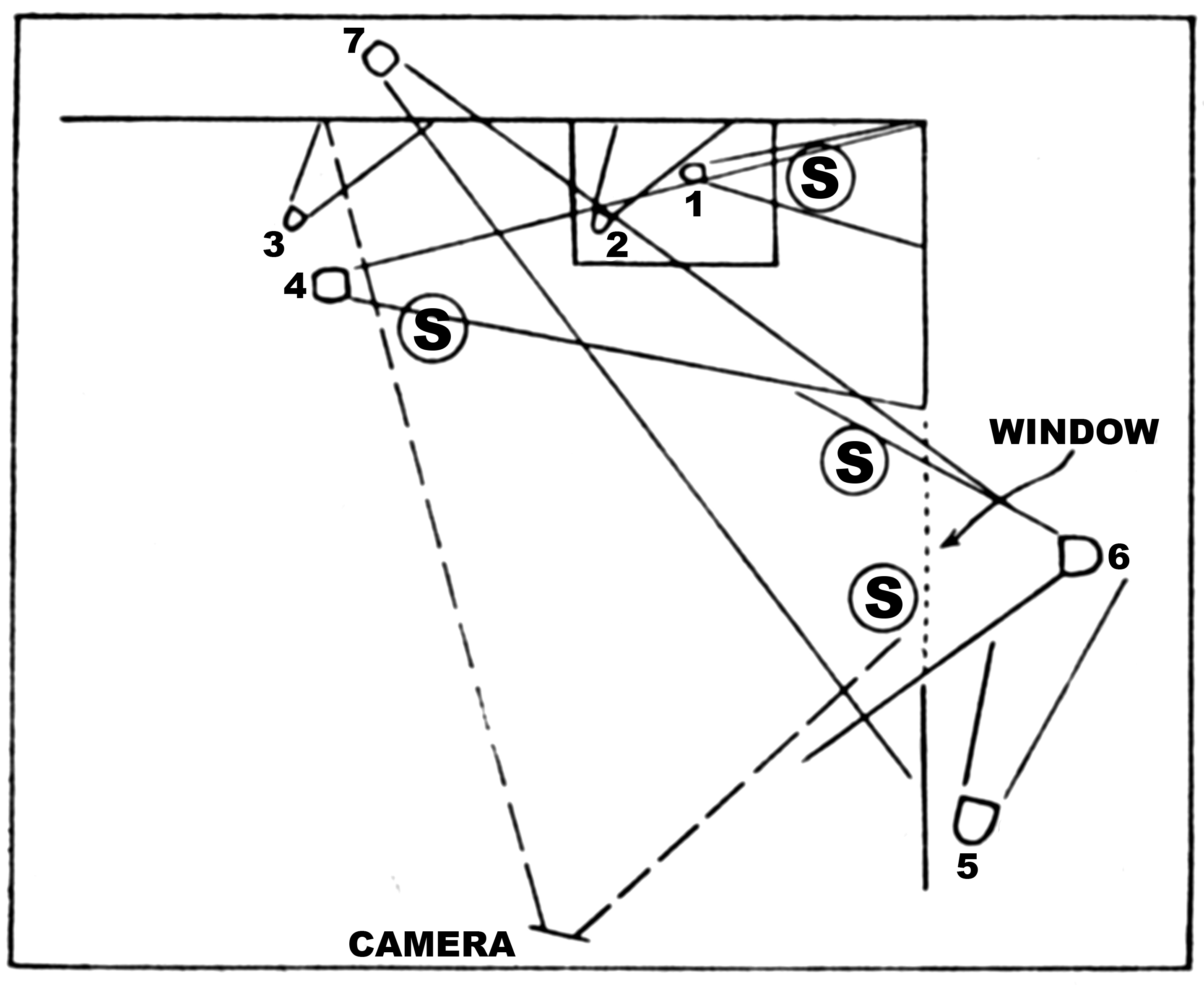

Figure B is another candlelight scene. Here, the problem was to provide a convincing effect of candlelight (with a trace of waning daylight outside the window in the left background) and yet provide the necessary illumination for the action — melodramatic swordplay — and to strike the correct visual mood for this type of action.

Again the key light was a 500-Watt Baby Keglight (#1) shining across the table and strongly illuminating the frightened man in the chair. It also served to illuminate part of the back wall behind him, and to throw upon it a pictorially strong shadow of man and chair. Baby key #2, placed high on the lamp deck, served a similar purpose for the masked swordsman and created a strong highlight on the white back wall, against which his dark garments stand out prominently.

The alcove in the background was illuminated by lamp #3 — a heavily-diffused Broad — while the effect of pale sunlight coming through the window in the background, and projecting its shadow pattern on the far wall at the left, was produced by a heavily diffused arc spotlight placed outside the window #4.

It will be obvious that since the swordsman stands leaning against the tall candlestick, the chief illumination on his face and figure should come from that source. It actually came from lamp #5, a Dinky Inky, placed on the floor slightly nearer the camera than the candlestick, and concealed from the lens by the table and chair. Another Inky, #6, with its beam flooded and diffused, completes the lighting by lightening the shadows on the corner behind the players.

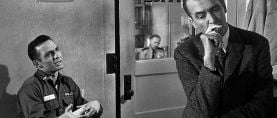

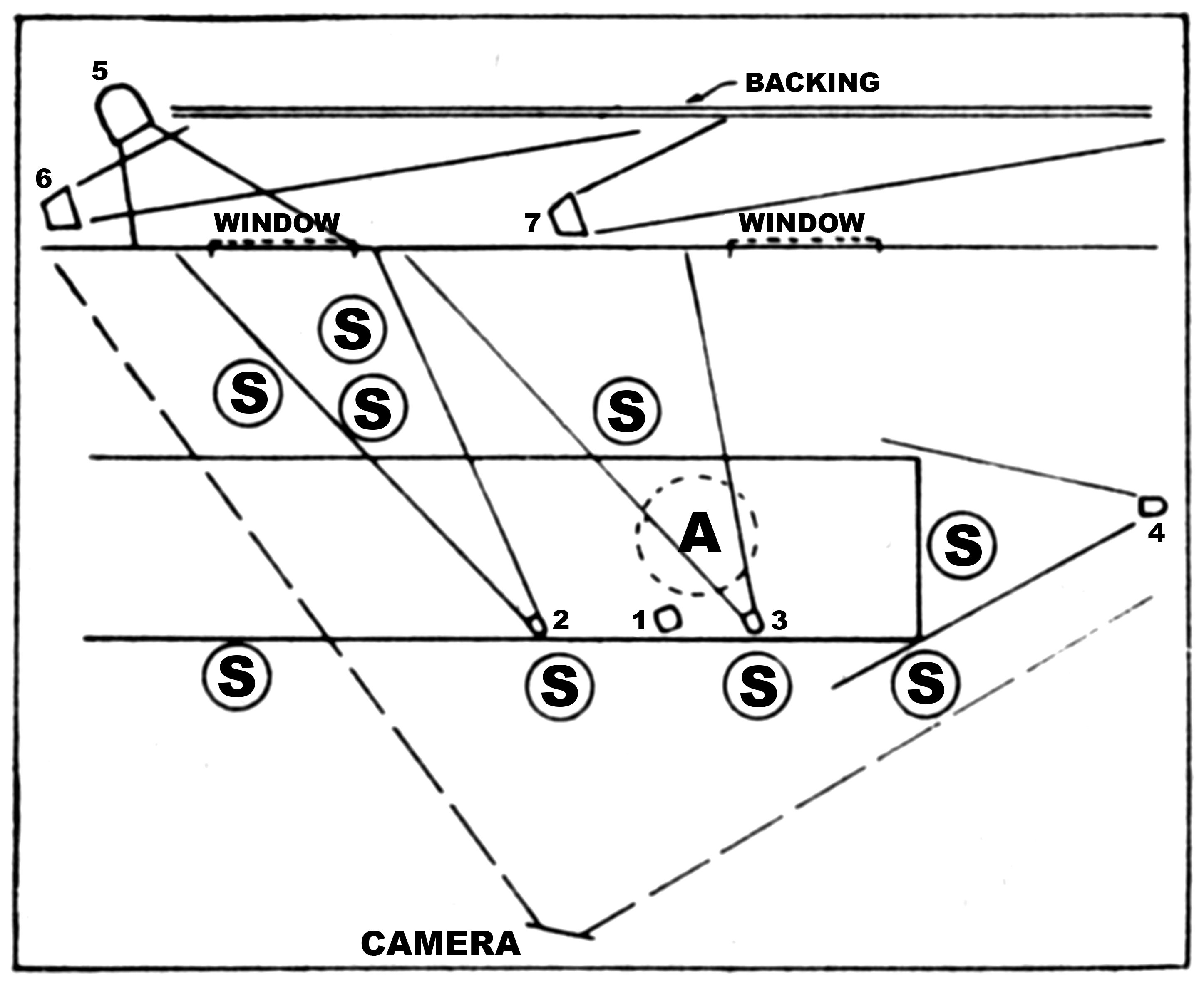

In Figure C, we have another candlelight effect — this time played in a more somberly dramatic mood. The principal source of illumination appears to be the candle on the table. This was simulated by Dinky Inky # 1, placed on the table, concealed behind the tall hat, which threw its beam strongly up into the face of the actor in the background, and projected his shadow on the back wall. A second Inky #2, similarly concealed behind the hat, throws its more diffused beam against the other wall, also simulating the candle’s light. Inky #3, on the floor at left, continues this effect, and silhouettes the man in the left foreground, #4 a Baby Keglight placed well to the left, outlines the man in the foreground on that side, and aids in lighting the background actor and the wall behind him. Another Baby Keglight #7 on the back lamp deck is crossed to illuminate the two men on the right.

The lighting is completed by the use of two arc spotlights. #5 was used to illuminate the backing outside the window. #6, well flooded, shone through the window to provide rim lighting on the two figures at the right.

Figure D is an example of the simplicity of dramatic effect lighting. The principal source of the light would obviously be the oil lamp suspended over the table. This was made the source by placing a Photoflood bulb inside the lampshade at “A” and reinforcing this source with lamp #1, a Baby Keglight placed overhead.

The strong key lighting on the group of three by the left window — especially centering on the distant figure, was provided by lamp #2, a Dinky Inky, placed on the table and concealed from the camera by the man seated in the foreground. The equally strong lighting on the other man seated behind the table was provided by Inky #3, placed on the table in much the same way and concealed from the lens by the man standing in the foreground. Lamp #4 — another Inky — gave the rim lighting necessary to make the man standing at the end of the table stand out well from his dark background. Lamp #5, a diffused arc spotlight, provided the effect of faint light coming in through the left-hand window while Broads #’s 6 and 7 illuminated the backing outside the window.

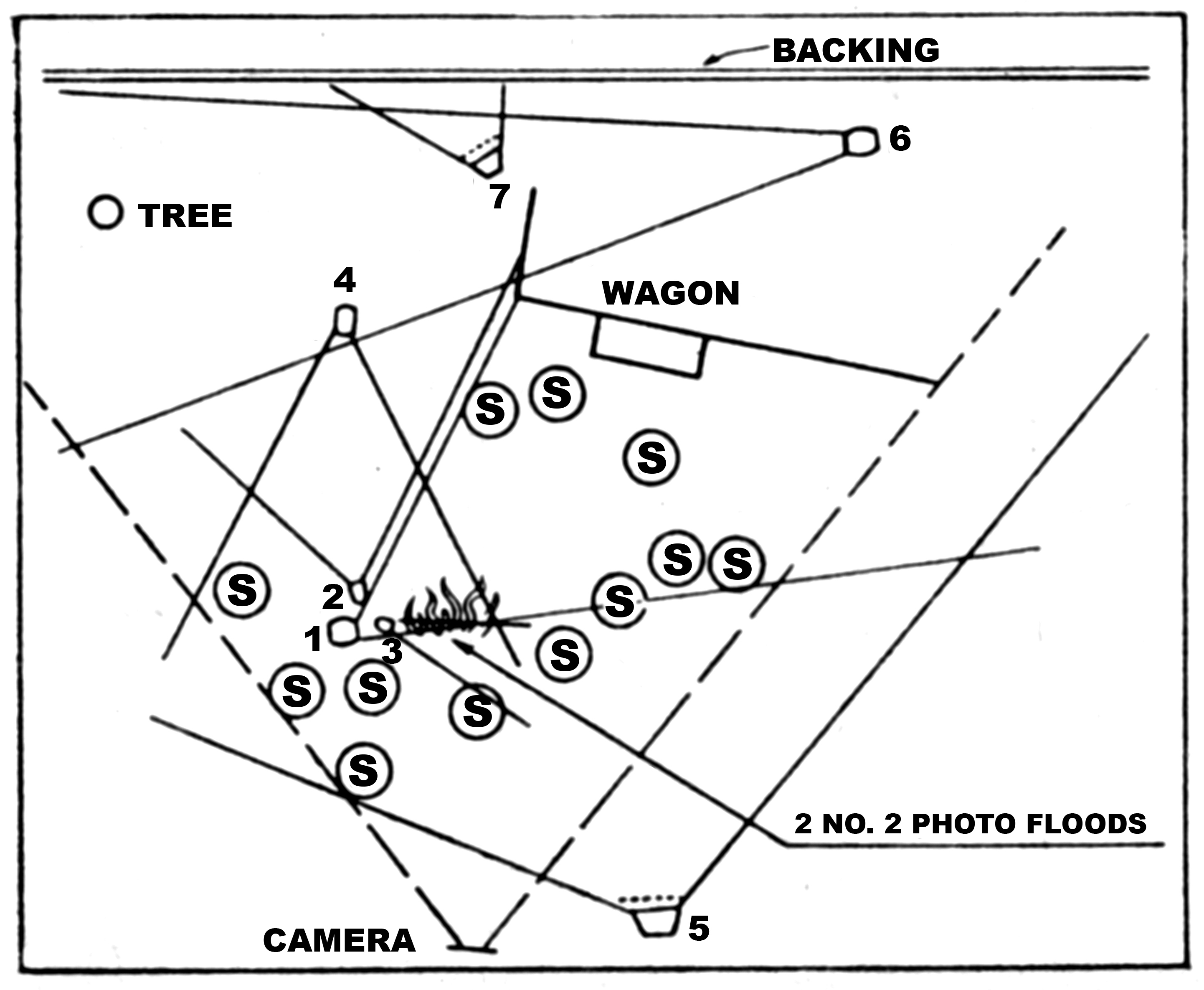

But Dinky Inkies are by no means the only units, which can at times be concealed within the scene. Figure E illustrates this. Here we have a stage exterior night effect. In this, the principal light source is, of course, the fire. To begin with, two No. 2 Photoflood globes were placed behind the fire; the flickering firelight effect was created by the usual gadget, which burns an oil-soaked wick in a metal pan directly behind these lamps, so that the smoke interrupts their beams to produce the requisite flicker and variation of intensity.

The chief light source on the principal players in front of the wagon was a Baby key, #1, placed low on the ground by the fire, and concealed by the men sitting in the left foreground. Lamp #2, an Inky, similarly placed, illuminated the man standing at the left, while #3, another Inky, highlighted the two men sitting at the left by the fire. Lamp #4 a Baby Keg placed high on the lamp deck, at the rear left, was used to rim light the players at the left and center foreground. Extremely soft front lighting was provided by lamp #5 — a heavily diffused Broad.

The background was highlighted by lamp #6, a Baby Keg placed high at the right and crossed, while the backing was illuminated by #7, another diffused Broad.

The point which I hope these somewhat obvious examples discussed will make is this: That these natural source-lighting effects, together with many similar ones they suggest, would have been absolutely impossible previous to the introduction of today’s high-speed emulsions and less-powerful lamp units that the speed of these films have made possible.

Cinematographers have always looked forward to the day when they could get truly natural lighting effects, and work at substantially natural levels of illumination. Today, thanks to these modern technical developments, we have come incredibly close to being able to achieve this long-sought goal. While average interior light levels are of course subject to considerable variation, due to differences in the methods of individual directors of photography and to the processing standards of the different laboratories which handle their film, a surprising majority of cinematographers are working only slightly above normal practical room-lighting levels

It should be pointed out also that this remarkable development has had, in addition to its artistic benefits, very definite technical and economic advantages as well. By eliminating the need for high illumination levels and the larger and bulkier lamps necessary for many of the makeshift techniques formerly needed to make these larger lamps adaptable to the fine, precision lighting these effects demand.

Summing the matter up. Today’s cinematographers are most fortunate that we can today reap the benefits of these advances in film, lenses and lighting equipment, which on the one hand make it possible at last to light with the precision necessary to obtain really natural lighting effects, and on the other, to greatly simplify and expedite the work of directors of photography and their stage crews.

The introduction of small incandescent lighting units in the 1940s, the Tungsten-Halogen revolution of the 1960s, the HMI daylight balanced units of the 1970s and today’s development of miniature LED units constitute a significant step forward in the technology of motion picture lighting. All of this, coupled with the digital capture we now enjoy a genuine breakthrough in the art and craft of cinematography.

Please note Mr. Miller’s comments on how his lighting gives added dramatic value and reinforces the portrayals of the actors. This demonstrates the true art of cinematography.

A clarification of lighting unit terms used by Mr. Miller:

Baby Keglight: also called Baby or Keg (because of the barrel-like shape of the fixture). A 6" Fresnel spotlight using 500-, 750- or 1000-Watt globes.

Dinky Inky: Also called Inky Dink or Inky (denotes smallest incandescent). A 3" or smaller Fresnel spotlight using 50-, 75-, 100-, 150- or 200-Watt globes.

Broad: Also called a Broadside, single Broad (one globe) or double Broad (two globes). A flood-type unit, rectangular in shape, with Factorlite diffusing glass in front. Uses 500-, 750-, 1000- or 1500-Watt globes.

Excerpted from Charles Clarke’s Professional Cinematography (1968)