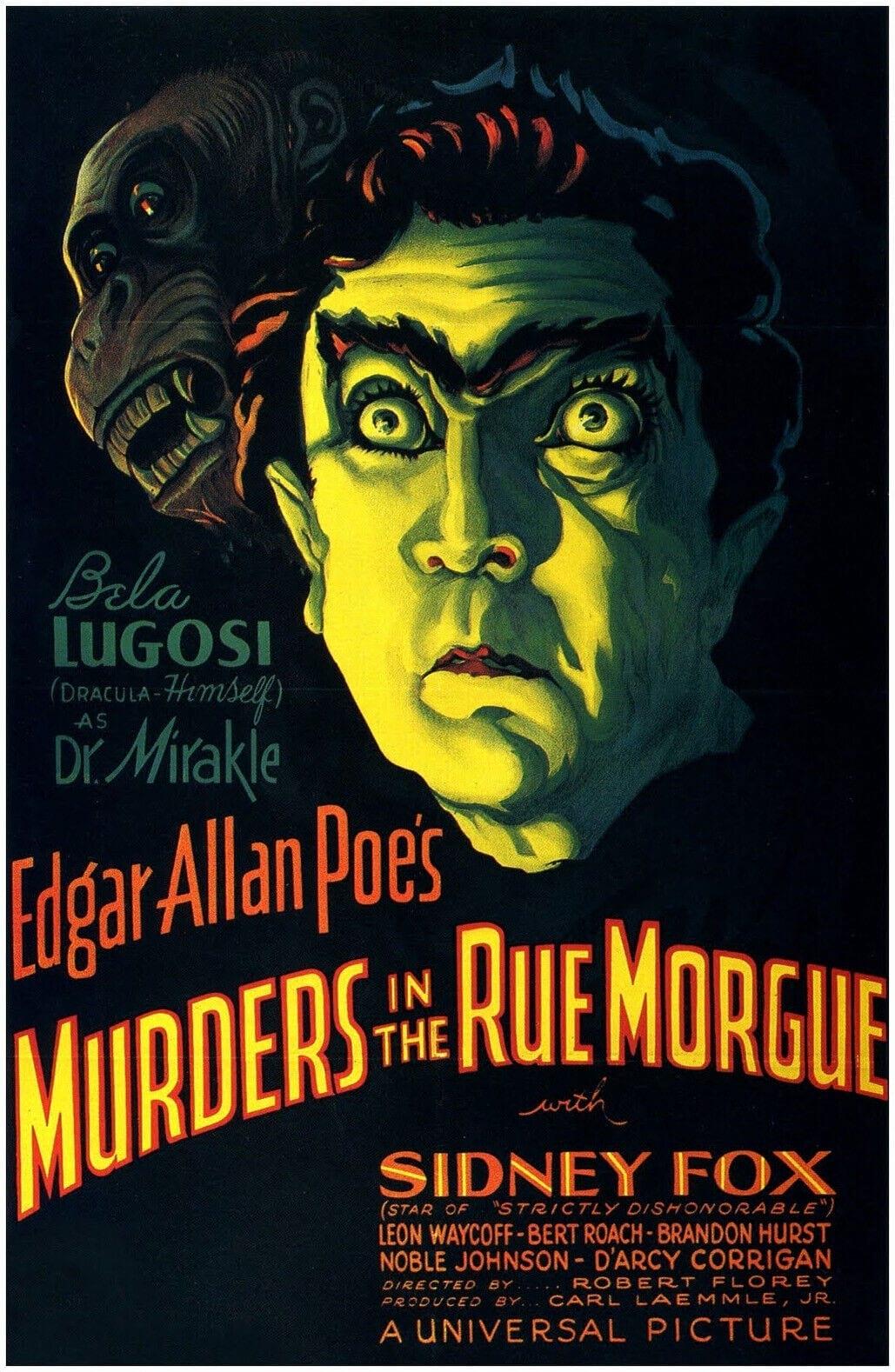

Universal’s Tradition of Horror: Murders in the Rue Morgue

A look back at director Robert Florey’s tumultuous journey from Frankenstein to this influential yet underappreciated classic.

This article originally appeared in AC April 1987.

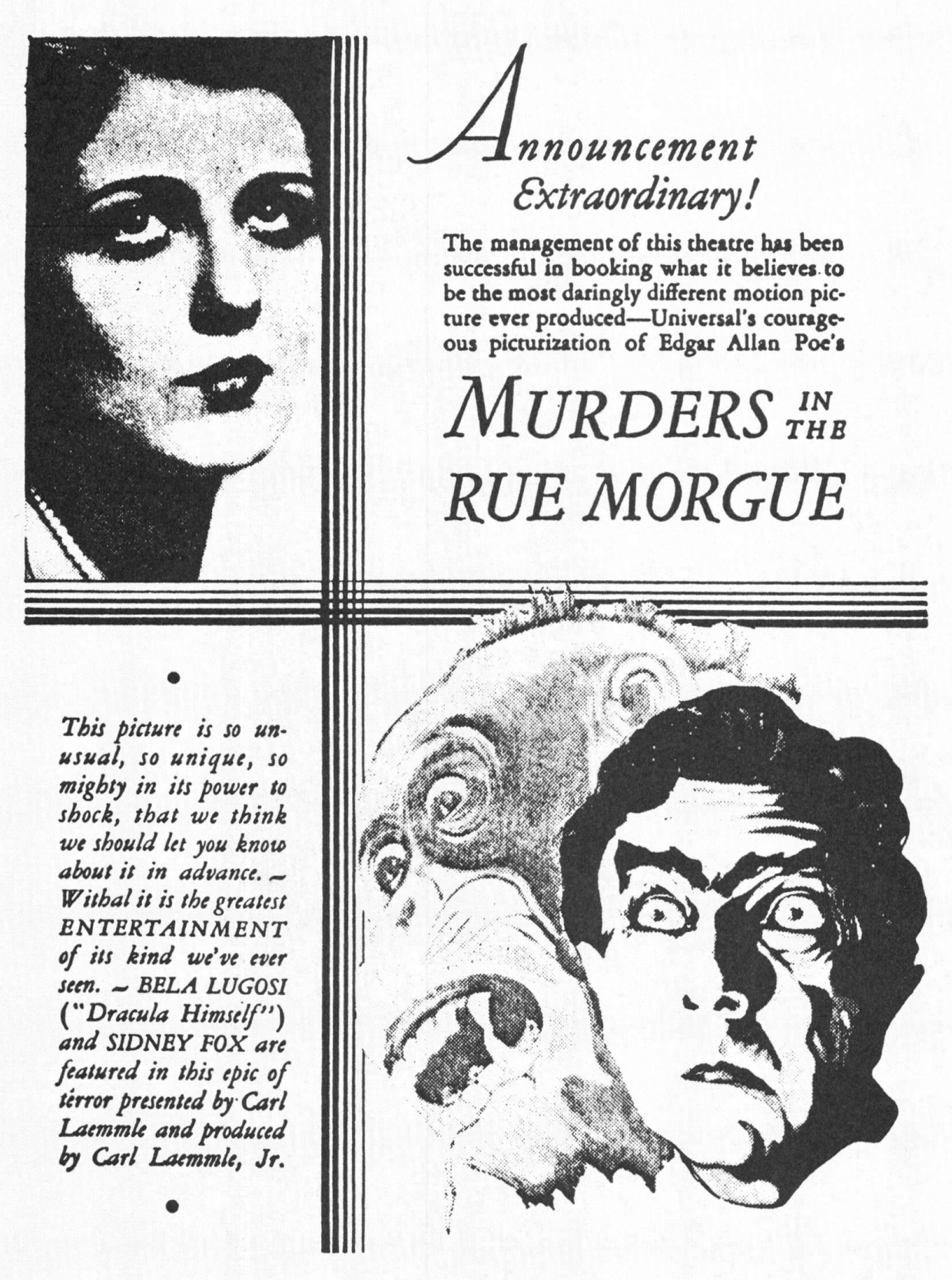

The indebtedness of the 1930s Universal horror cycle to James Whale and Boris Karloff has been amply discussed over the years, often at the expense of others who contributed equally. Another pair, arguably more influential in initiating this cycle although their contributions are seldom celebrated, was the team of Karl Freund, ASC (cinematographer of Dracula (1931) and Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932)) and Robert Florey (co-screenwriter for Frankenstein (1931) and adaptor/director of Rue Morgue). The talents of Florey and Freund complemented one other, and both won some of their greatest fame for their efforts at Universal.

While Universal horror talkies began with The Cat Creeps and Dracula, the cycle was not fully launched until Frankenstein and Murders in the Rue Morgue, which between them created the motifs and conventions that would define the genre’s future parameters. However, Rue Morgue has been often neglected by historians, partly as a result of its coming about as an indirect result of Frankenstein and Dracula. To understand how this occurred necessitates relating the saga of preparing Frankenstein for the screen, a tale that has never yet been fully or accurately told.

The genesis of the original Frankenstein is one of the most controversial episodes in film history, having become obscured over the years by the star mythology surrounding Karloff and Whale. Frankenstein was originally scheduled to unite Freund as photographer and Florey as writer-director; later James Whale would direct from Florey’s script and plans, a fact few are aware of because Universal removed Florey’s name from the screen credits. But Florey’s original, hand-amended directorial continuity survives, and it is possible to trace the precise development of Murders in the Rue Morgue from Dracula and Frankenstein, the effects this trilogy had on Universal, the horror genre, and the futures of all the individuals involved.

With Dracula Universal had filmed a hit stage play with its star, Bela Lugosi, releasing the picture in February of 1931 to major box-office business that eventually grossed $500,000. This result seemed to promise a popular new trend for a financially unsteady studio, and Universal eagerly sought ideas for another horror film to include Lugosi. The next month one of those contacted was Robert Florey, a young writer-director with 15 years of training in the cinema and 11 features to his credit. He had directed the Marx Brothers’ screen debut in The Cocoanuts (1929) and made some of the first French talkies at Ufa in Germany and elsewhere in Europe.

Together with Richard Schayer, head of the Universal story department, Florey discussed a number of possibilities for a new Bela Lugosi chiller including adaptations of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Edgar Allan Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue, and H.G. Wells' The Invisible Man. Recalled Florey:

“Schayer first mentioned Frankenstein. It was not my idea... Schayer said that [it] would be extremely difficult to write an adaptation. I answered that it would not be if the plot was changed a little. He wanted to know how. ‘Give me a few days,’ I answered, ‘and I might think of something.’... In less than a week I had written a five- or six-page adaptation and I phoned Schayer. We lunched together the same day at the studio and after listening to my idea he was very enthusiastic.”

Florey made an appointment later that afternoon with the 22-year-old boss of Universal. Florey won approval for his ideas during “a singular interview, while Carl Laemmle, Jr. was delivering his fingers to a manicurist, his hair to a hairdresser, his thoughts to his secretaries, and his voice to a dictaphone. ...I [was] signed as a director and a writer, the contract not specifying that I should direct a story I wrote or adapted.”

Florey’s services had been sought because of his knowledge of the Grand Guignol repertoire and Schayer’s admiration for two earlier films Florey had made depicting the return of the dead to the realm of the living. These were Paramount’s The Hole in the Wall (1929), the first talkie for both Claudette Colbert and Edward G. Robinson, and an independent, Poe-like three-reeler, Johann the Coffin Maker (1928), shot over a weekend for under $200. The latter had been one in a series of experimental efforts, beginning with The Life and Death of 9413 — A Hollywood Extra, that first alerted the major studios to Florey’s talent. Their bizarre set design, shadowy lighting, avant-garde compositions and camera angles foreshadowed the visual style of Florey’s later movies, especially his thrillers.

Florey’s conception for a film of Frankenstein was derived from the tradition of German expressionism; his enormous debt to this style exceeded that of many of the German emigres themselves. Preferring F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) to Universal’s Dracula, Florey set out to make a horror film in the continental spirit, rather than the Anglo-American school. Using elements drawn from plays presented by the Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol (in which he had been involved as a teenager), as well as The Golem (1920) and incidents from other German expressionist films, Florey came up with a plot only loosely connected to the novel. With the Frankenstein script, Murders in the Rue Morgue and his later thrillers, (such as The Florentine Dagger (1935), The Face Behind the Mask (1941), and The Beast With Five Fingers (1946), Florey would prove supremely gifted in both writing and directing stories imaginatively mediating elements of mystery and horror.

From May 15 to June 20, 1931, he refined his ideas into screenplay form. Although he had worked alone on the adaptation, Florey now collaborated with Garrett Fort, who had prepared Dracula for the screen; as in the case of all of Florey’s scripts, his partner’s principal contribution was in writing the dialogue. Eventually, a final shooting continuity was completed with every composition, camera angle, setup, lens, and sound and special effect described in minute detail. Almost 500 individual shots were so enumerated in the script.

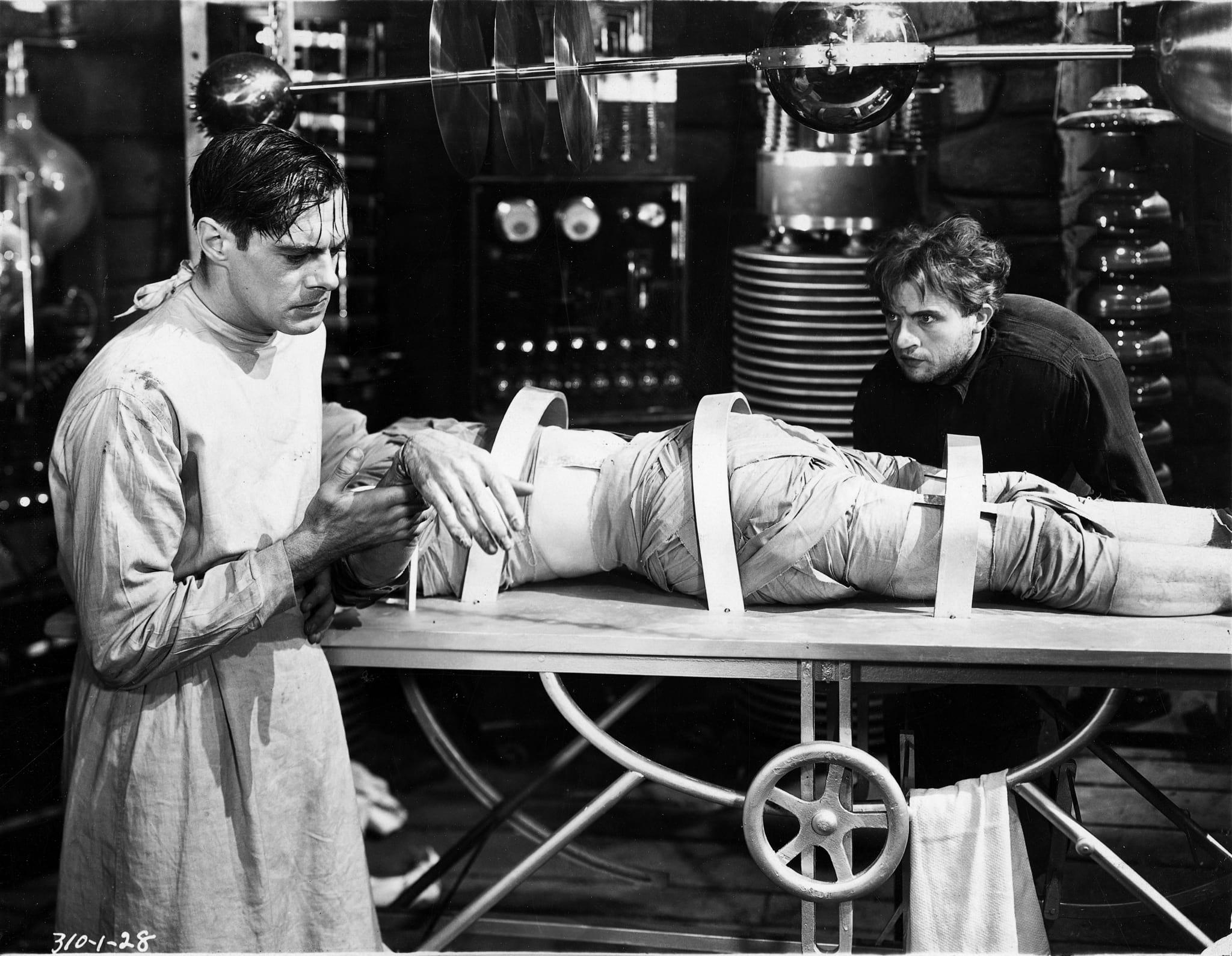

The studio hierarchy then asked him to demonstrate by shooting a sample scene how Frankenstein would be visualized. This “was not merely designed to test the make-up,” the director recalled, “otherwise they could have shot a couple close-ups and long shots of the Monster..." They wanted to see, remembered Paul Ivano, ASC, whether “a film with a principal character with such a grotesque appearance could please the public.”

For this purpose, a couple of stock players, along with Lugosi and two other veterans of Dracula who were to be featured in Frankenstein, Edward Van Sloan and Dwight Frye, were brought together. Although Karl Freund was scheduled to photograph Frankenstein, an independent cameraman and lighting specialist, Paul Ivano, was brought in to shoot the test. Ivano had distinguished himself for his artistic ability alongside such demanding directors as Josef von Sternberg (The Sea Gull, An American Tragedy), F.W. Murnau (Four Devils), and Erich von Stroheim (Queen Kelly).

By now, Universal had determined that the role of the monster, rather than that of Dr. Frankenstein, would be more in accord with the persona they wanted to cultivate for Bela Lugosi — despite his appearing in non-horror films at competing studios during the months since Dracula. This reversed the original intention of Lugosi portraying the scientist, as Florey had assumed while writing the script. The star himself was enraged at being asked to enact a mute role that he believed secondary and which would force him to spend most of each day hidden beneath uncomfortable makeup.

However, the cast and crew assembled under Florey’s direction in the interior of the Dracula castle tower on Stage 12 on June 15, 1931. The Frankenstein test was then shot in continuity, covering the sequences of the visit of Frankenstein’s friend, Victor Moritz, to Dr. Waldman (Van Sloan), and their arrival at the windmill, through the subsequent birth of the monster. The segment between these two scenes, of Frankenstein’s preparations for the storm with Fritz (which does appear in the movie), was not included. In this version of the screenplay, and so in the test, Frankenstein’s fiancee did not appear in either scene, although she would in the final picture.

Despite Lugosi’s protests, he brought off his small part capably. Contrary to myth, his acting and appearance were virtually identical to those of Boris Karloff, as both Florey and Ivano remembered. Even with Lugosi’s temper, which included pulling off the bolts Florey had whimsically added to his neck, the test was shot on June 16 and 17 after a day of rehearsals. (Ivano received $109.38 for 17.5 hours of work.) Over 3,000 feet of film was exposed and edited down to a form suitable for theatrical presentation, lasting two reels — about 20 minutes.

Although the test seems to have become lost or destroyed, its appearance can be described through personal reminiscences and reference to Florey’s directorial continuity, revised in his own hand. Through these sources, it is possible to reconstruct how the test must have looked. Most of the events, but not all of the shots, which appeared in the test can be found in Frankenstein, although there are some significant differences. For instance, Florey intercut Fritz’s (Frye) theft of the criminal brain and the discussion between Waldman and Victor, rather than separating the two scenes. (While Florey contributed the idea of the theft of a criminal’s brain, it was a later writer who elaborated Fritz’s thievery into taking the criminal brain when he dropped the intended normal one — an addition typical of Whale’s black humor.) Some clever ideas were deleted by Whale, such as a direct-address shot of Waldman as he announces that Frankenstein was only interested in creating human life, and the monster’s cranial implant demonstrated by analogy when Waldman flips off, like a coffee pot, the top of a human skull used as a tobacco container.

Whale apparently shortened significantly the scenes covered in the test. In the final movie, these take up only 45 shots, whereas the Florey-Fort continuity of this segment was broken down into 69 separate shots (and the actual test probably included more, with the addition of dialogue reaction shots during the photography and editing). Some of this difference can be accounted for by the considerable alteration and abbreviation of Fort’s original dialogue, along with Whale’s reliance on long takes as opposed to Florey’s preference for frequent cuts and changes of camera angle.

For Florey, the creation scene was to be the stylistic highlight of Frankenstein, planned in an extremely expressionist, even surreal manner. The setting was originally in an old mill, and four pages of the script were spent in the description. The laboratory, according to Florey, “was set looking like a medieval cave or the inside of an old tower with a spiral staircase in the background.” The script indicated “it is more impressionistic than scientific, and designed to create a feeling of modern scientific ‘magic’ — something suggestive of the laboratory in Metropolis... The lighting is weird and unearthly.”

Cinematographer Paul Ivano supplied his recollections to Rene Predal, translated here from French for the first time:

“Dr. Frankenstein and his assistant descended the staircase, our Mitchell camera [placed in the center] taking 360-degree panoramic shots of the decor, stopping in front of the table where the monster was stretched out lifeless... Since the decor was similar to the interior of a well, I was obliged to light the scenes from above but as the distances were large, I used incandescent lamps of 5,000 watts. The film was still very slow at this period...”

Only some three-fourths of the way through the test did Lugosi as the monster become involved; the first 15 minutes centered around Victor, Waldman, Frankenstein and Fritz. Recalled Florey, “The electrical gear we used was not as elaborate as the one used in the final version, we had just a few props.” During the storm, there were double exposures, such as Frankenstein’s face over the electrical machinery during the storm and lightning, along with several 12-frame negative strips of flash close-ups of the three observers of the scene.

Said Ivano, “At the moment when the camera framed the group of the three characters [Frankenstein, Victor and Waldman], the electric shocks and other light effects were produced then and the monster began to move, lifting himself quietly and opening his eyes.” With the monster’s chalky face previously seen by the audience while still lifeless, the resuscitation was indicated not only by the movement of an arm, but also by his hand slowly changing on the screen from black to white as (according to the script) “a whimper, like that of an animal in pain, was emitted.” This last effect, deleted from the final film, was later included in The Bride of Frankenstein.

Ivano recalled “numerous bizarre angles creating a nightmare atmosphere for these sequences, a rather rare thing for that time. The camera was almost always in movement, following the characters ceaselessly. These trials were so successful, so beautiful from the artistic and photographic point of view, that all the directors of the studio wanted to make the film.”

Florey echoed Ivano’s memories: “I was very happy with the test. I shot most of it with wide angles and the camera always in motion. Schayer had told me that if the Laemmles were pleased with it I would certainly direct the picture... The reaction from the studio brass was excellent.” The satisfaction felt with Lugosi was indicated when, sometime later, James Whale still considered him for the role of the monster even as he chose Colin Clive to play Dr. Frankenstein; Boris Karloff was cast in Lugosi’s stead only over the stiff opposition of young Laemmle.

Laemmle’s doubts were more than satisfied, and he believed Frankenstein had important commercial potential; even Lugosi acquiesced temporarily, handing Ivano a $5 cigar and exclaiming, “My profile looked magnificent!” The promise displayed by the work of Florey, Fort, Ivano, and Lugosi was so great, however, that Whale now demanded Frankenstein for himself. Since Whale had the extensive stage experience so prized during these early days of talkies, Laemmle, often inconstant in dealing with his employees, willingly granted the request. Leon Ames, set for a role in Murders in the Rue Morgue, recalled, “Universal at that time was a very odd place to be. Carl Laemmle Jr. was a kid, a strange little fellow, who seemed to run the studio more as a plaything, because his dad liked him, than as a knowledgeable producer.”

Whale chose Arthur Edeson, ASC as his cinematographer, and it is to Edeson that principal credit must be given for what quality cinematography Frankenstein does possess.

Florey had expected to begin directing Frankenstein within a month of completing the test. Abruptly, however, he was asked to assist in trying to adapt Murders in the Rue Morgue into movie form. Several writers had been stumped despite many weeks of effort, and Florey seemed a promising candidate for the task with his reputation as the man who successfully made a screenplay from Frankenstein. Only later did he discover with anger and disappointment that Universal had officially transferred him, along with Lugosi, to this new project. “I was not informed of what was going on but offered a contract to direct a feature based on Poe’s Murders in the Rue Morgue which I should adapt for the screen. Then I heard about Frankenstein being prepared by Whale but I couldn’t do a thing about it; I consoled myself by thinking that I would share the writing screen credit with Garrett Fort and have another credit on Rue Morgue.”

However, in a second, even more disheartening move, the studio eliminated Florey’s name from the scriptwriters listed on Frankenstein, in spite of the few changes made after his transfer (principally by Francis Edward Faragoh, who was credited along with Garrett Fort). Florey could only be partially consoled when protests caused his name to be reinstated and listed as sole co-author with Fort on the European release. Naturally, Florey resented such treatment and as soon as he received another offer of employment, in early 1932, he left Universal.

At first, Rue Morgue appeared to have distinct disadvantages in comparison to Frankenstein. Florey remembered Universal “wanted to produce Morgue quickly and cheaply.” As the second horror movie put into production to capitalize on the success of Dracula, Murders in the Rue Morgue was to be made for $100,000 less than Frankenstein. In spite of these shortcomings, Rue Morgue finally allowed Florey to realize the stylistic intentions expressed in the script and test for Frankenstein, and he also had the assistance of a truly expressionist cinematographer in Karl Freund, ASC.

Even with his fondness for Edgar Allan Poe, little remained of the original Murders in the Rue Morgue in Florey’s version. Only two incidents from Poe’s plot were even used: the grisly discovery of a woman’s corpse stuffed up a chimney and the humorous argument over the language spoken by her murderer (later discovered to have been an ape). This scene was preserved because of Florey’s sometimes light-hearted approach to the ghoulish; “I do not think that humor dilutes the effect of a film of this type, otherwise it becomes too macabre... In the Grand Guignol plays they often mix terror with laughter.”

Since there was no one in Poe’s tale Lugosi was suited to play, Florey had to add a new individual - Dr. Mirakle, Dupin’s antagonist, “although the story would have been much better without the Mirakle character.” Nonetheless, Schayer was dissatisfied; Universal had determined to make Lugosi their new Lon Chaney, so the Poe original had to be altered even more to serve as a Lugosi vehicle, enlarging the horrific dimension. “Lugosi had to be some kind of a mad scientist or a monster... In my first adaptation, there wouldn’t have been much to do for Lugosi... The Dupin part was more important than the Dr. Mirakle part. However Lugosi was slated to star in the film and I had to build his character up, at the time Lugosi was no longer scheduled for Frankenstein.” A fanatical pre-Darwinian evolutionist, Mirakle attempts to prove mankind’s kinship with the ape by transfusions of blood between various women and his pet ape.

This final adaptation was completed in just over a week. Florey and Tom Reed collaborated on the continuity, while Reed later polished the script and wrote the dialogue with Dale Van Every. Universal finally granted Florey a share of screen credit, as the author of the adaptation, for his contributions to the script. Last to be brought in for “additional dialogue” was John Huston, in one of his earliest Hollywood credits.

Huston commented, “I tried to bring Poe’s prose style into the dialogue, but the director thought it sounded stilted, so he and his assistant rewrote scenes on the set.”

Florey, like many filmmakers with roots in the silents, was always eager to minimize dialogue. Leon Ames (making his screen debut as Dupin) remembered his director “used to say, ‘Do you feel comfortable with this speech?’" As Florey explained:

“It was not unusual at the time to rehearse each scene several times as it was better to rehearse without film than shoot film which wouldn’t have been good and start all over again, an expensive procedure. A foreigner like Lugosi liked to rehearse to be certain to be understood. We always checked with the sound man to find out if every word came out clearly and if not, we changed the word. Lugosi didn’t make suggestions for changes except when he was not able to pronounce a word correctly; he would then substitute a similar word. He was very adaptable to the script.”

Because of the necessity of restructuring the plot to accommodate Lugosi’s presence, there are influences at least as strong as Poe’s that affected the collaborators of the script. One, clearly was Frankenstein. That is hardly surprising; Florey had been preparing it for months and was suddenly given only days to come up with an entirely new scenario. There are a number of obvious similarities between Frankenstein and Rue Morgue: the scientist’s peculiar assistant (symbolically bridging the evolutionary gap between the doctor and his creature); the lab in an abandoned hovel; the monster’s superhuman strength; and the climax in which he attacks his master and is pursued by a mob.

Florey candidly admitted the resemblance: “I used the same device I had employed in Frankenstein. I do not think that [producer Eph Asher] had ever heard of Poe or of Rue Morgue before... The Universal people, not being particularly bright, didn’t realize that I again used the same plot, using an ape instead of a monster and this time giving the Doctor’s part to Lugosi. I called him Doktor Mirakle instead of Dr. Frankenstein, and I had him looking for human blood for his ape instead of a brain for a monster!”

Rue Morgue is also heavily indebted to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), and has been described as the German classic’s most direct descendant in the United States. Previously, around 1925, Florey had shot tests for a “Caligari-esque” experimental film entitled The Mad Doctor and starring Michael Visaroff; only a few stills survive, but in costume, make-up, pose and lighting they bear a close resemblance to the appearance of both Werner Krauss as Dr. Caligari and Bela Lugosi as Dr. Mirakle. William K. Everson has called Rue Morgue “if not a remake, then certainly a more than casual parallel” which proves Caligari to be “a constant source of design- or character-inspiration in Hollywood films.”

But Rue Morgue is also a popularization and Americanization of Caligari, taking the entire framed story of Caligari prior to the asylum, eliminating the undertones of political oppression, and with deceptive simplicity transforming the remainder into a Hollywood genre film. In this new context, the narrative of Caligari is made palatable to a mass audience.

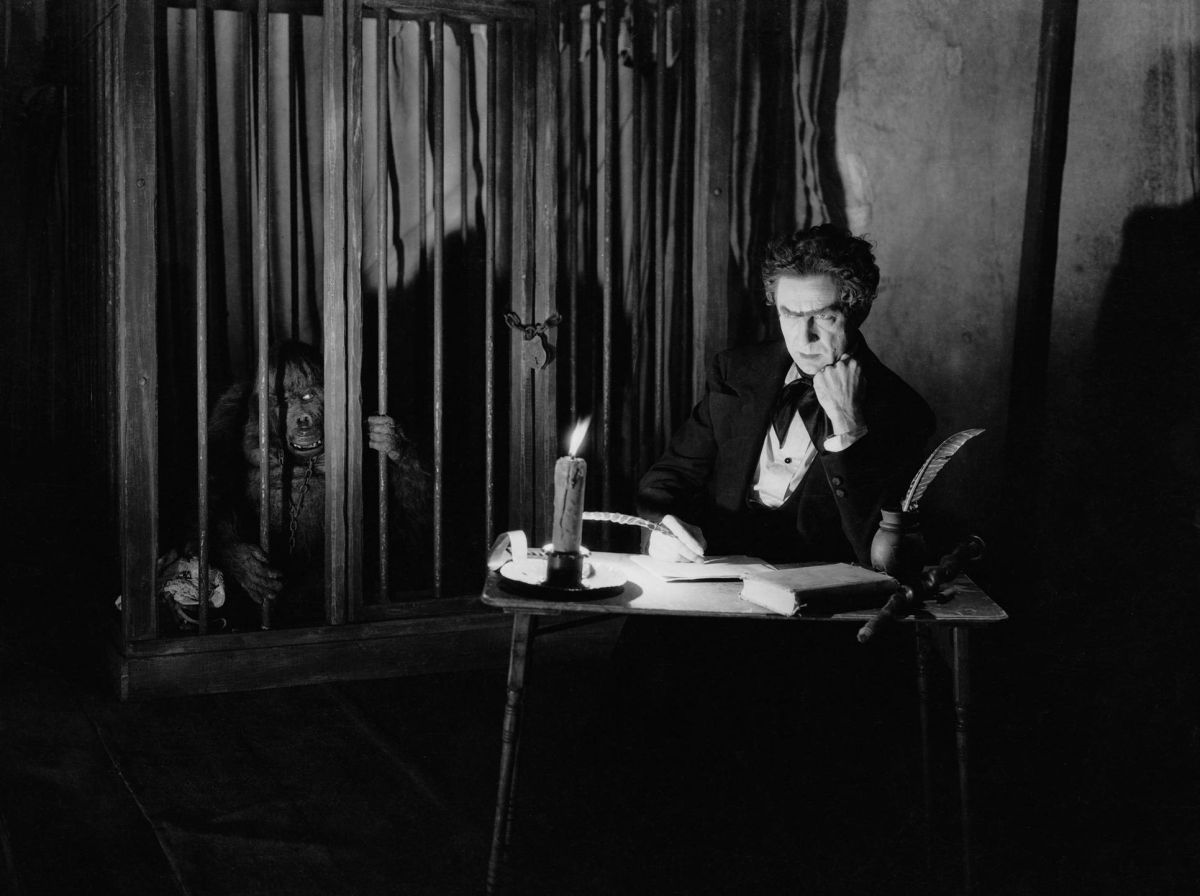

Each opens in a carnival, where one of the attractions is a tent where a mysterious “doctor” lectures on his strange theories and exhibits a type of animal to demonstrate them. Among the onlookers in Rue Morgue are Dupin, his fiancee Camille (played with delicate charm by Sidney Fox), and their friend (Bert Roach); precise equivalents to these five principal characters exist in Caligari. Mirakle’s orangutang and Caligari’s somnambulist are both controlled in a hypnotic state, and while the latter is sub-human, the ape has all the emotions of a man. The film’s doctors order the kidnapping of the girls by their creatures who, however, fail to behave as expected, and are chased by angry crowds as the girls are carried off.

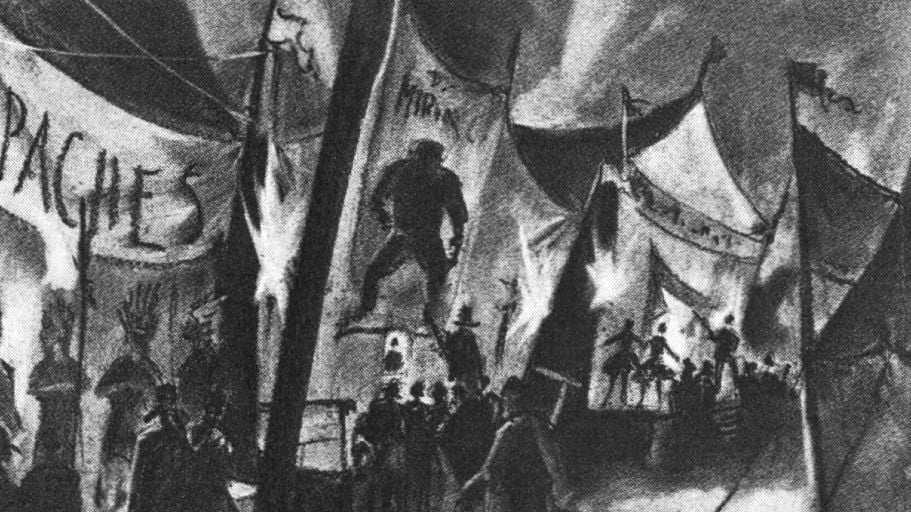

The Rue Morgue also has a Caligari-like visual design. The setting is not the familiar Paris; it is the mid-19th century, revealing the Boulevard du Crime, a dark underworld of temptations, menace and mystery. The lighting, composition and sets followed the artistic style of the story’s period, especially the paintings of Daumier, to obtain the proper ambiance. This period was a favorite of Florey’s; he had previously created it as technical director of MGM’s La Boheme in 1926.

Florey then joined with Charles D. (“Danny”) Hall, an art director best remembered for his many associations with Charlie Chaplin. At Universal, Hall handled the decor of many horror films; he also worked on several of Florey’s previous and subsequent movies. As they had done in preparing the visual style of Frankenstein during the time Florey was scheduled to direct it, the two men collaborated once more on numerous drawings of the sets prepared for each scene. These included the placement of shadows and Florey’s conception of distorted building design; many of the long shots from Murders in the Rue Morgue copied these sketches. Other set designs were contributed by Hermann Rosse, Dutch-born theatrical set designer who had recently won an Academy Award for Universal’s King of Jazz.

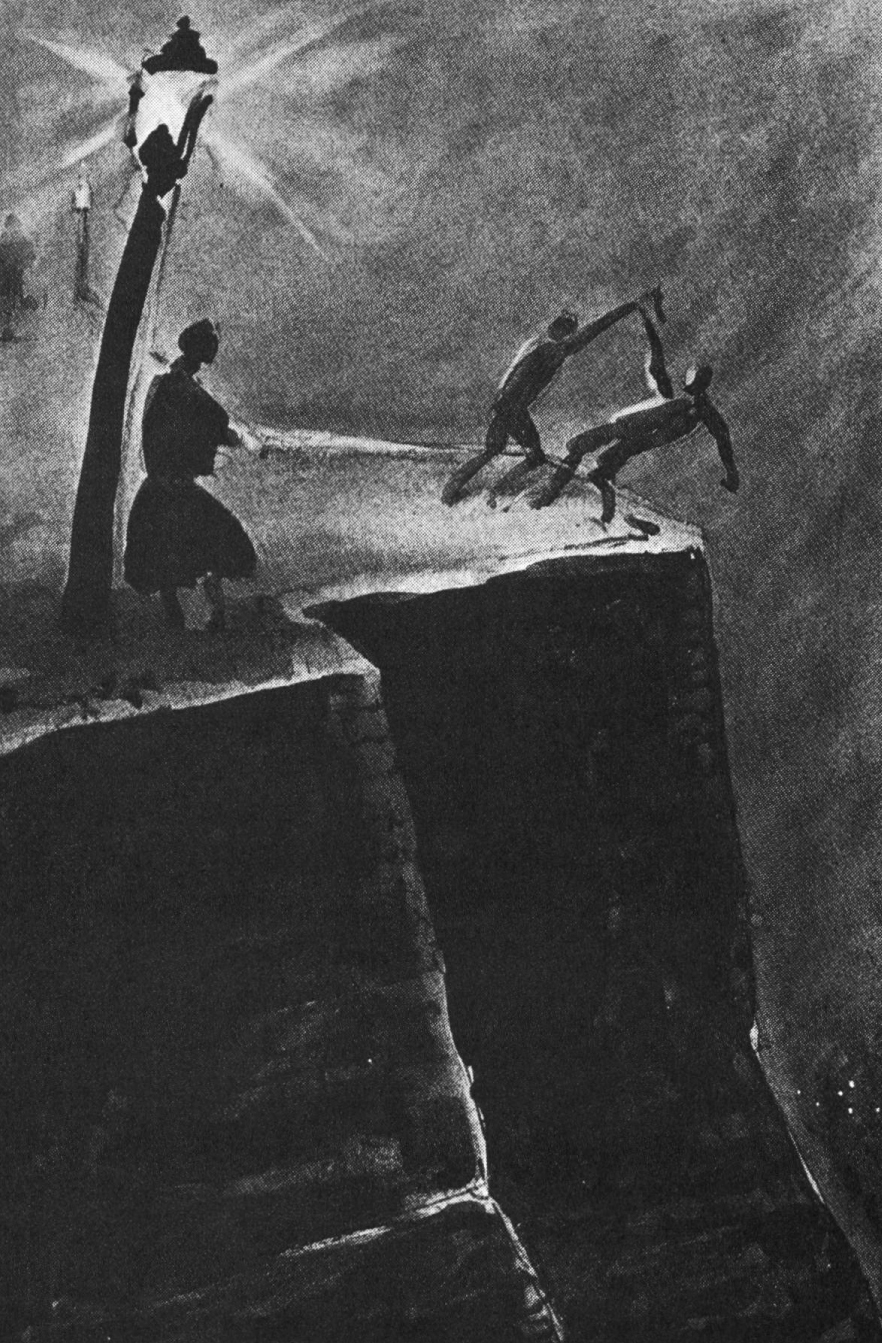

Hall and Florey surveyed the dusty sets searching for existing materials that could be converted to advantage. Old canvas flats standing around were used to create “angular doors and windows” and ceiling pieces for low angles. “It was easier to adjust or to lean canvas walls to obtain a certain angle or effect which I could not have gotten with a solid wall. “ Other exteriors and the final chase of the ape used the streets and rooftops left over from The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923). None of the Frankenstein village sets were utilized.

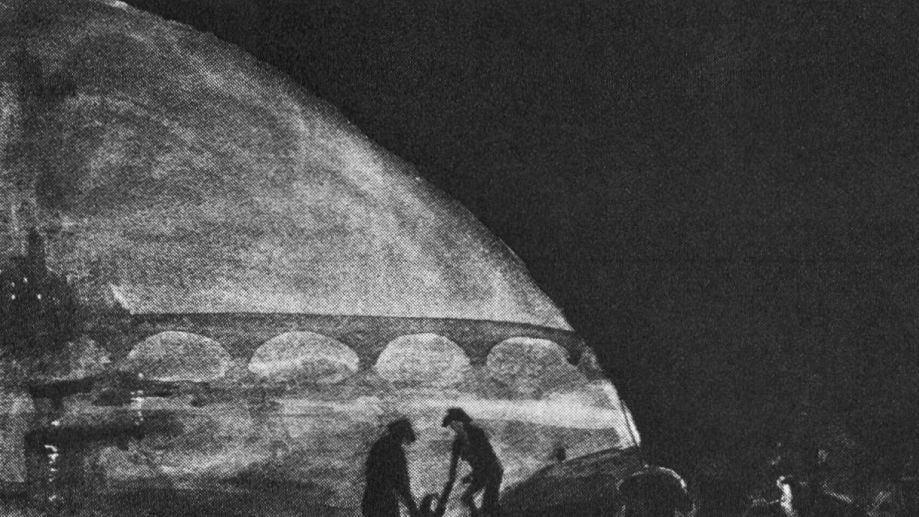

Special effects were handled by John Fulton and composite process shots by Frank Williams (the last for $1,875). Although done separately, their work combined well with the overall visual style and mood of the movie. They included “the matte shots over the bridge on the Seine and certain rooftop shots.” Florey continued, “The long shots [were] photographed through a top painted glass, such as the one used for the sequence taking place under a bridge over the Seine river or during a knife fight on the Paris fortification, these scenes being calculated and timed to correspond to a sketch.”

The various elements were used in an expressionistic manner to create the desired mood and atmosphere. Everything, even the apparently normal, such as the carnival and the empty streets, is suffused with foreboding. Characters appear and are devoured by fog and shadows; two men are seen murdering one another by a river, their indistinct movements half concealed by a fast-blowing mist. Nearby, the prostitute (Arlene Francis) they quarreled over watches hysterically — before she is taken by Dr. Mirakle into his carriage, another subject to be sacrificed to his experiments.

Few Hollywood films have been so thoroughly dominated by the Germanic style in conception and treatment, from narrative to set design to photography. The key reason was that the film was made by a team unique for their immersion in the expressionist tradition — Florey and cinematographer Freund. This was not the only such advantageous association on Florey’s feature films using the expressionist style: others included George Folsey, ASC (The Hole in the Wall); Karl Struss, ASC (The Preview Murder Mystery); Rudolph Mate, ASC (Outcast); William Mellor, ASC (Hotel Imperial); Franz Planer, ASC (The Face Behind the Mask) and John Alton (The Crooked Way).

Freund was 41, with a quarter century of experience in the industry. In Germany, he had already won a secure place in film history as the individual most responsible for exploring the mechanisms and potential of the moving camera. His credits comprised a list of masterworks including part one of The Spiders (1919), The Golem (1920), The Last Laugh (1924), Variety (1924), Tartuffe (1925) and Metropolis (1926), working with such directors as Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau. In late 1926 Freund left active cinematography to become head of production at FoxEuropa, then began scientific experiments with sensitized film, sound and color, leaving for London and finally coming to America in 1929 under contract to Technicolor. However, various technical and financial problems arose, with the result that in 1930 he landed at Universal, once more a cinematographer.

Freund and Florey shared similar artistic ambitions and stylistic tendencies. Both were eager to innovate, to create a European-type horror film in the context of the classical Hollywood studio and genre systems. As individuals, they were personally compatible; “It was a pleasure to collaborate with him as he understood exactly what I wanted,” said Florey. For instance, they took advantage of their knowledge of the other’s native language; Leon Ames recalled he “never knew whether they were speaking German or French!” Said Florey, “I was an admirer of his films as I had seen most of them. He responded to my specific efforts and helped me greatly with his suggestions. He was an expert in unnatural lighting effects, and Whale should have taken him [for Frankenstein] instead of my other friend, Arthur Edeson.

Ames remembered that whenever Florey or Freund had any trouble with their lighting, they didn’t waste time. “If they couldn’t get the right shadow, he’d have ’em paint it” — a typical procedure for the early expressionist films. Wrote Florey:

“Freund responded to my specific efforts and helped me greatly with his suggestions. He also chalked lighting effects on the walls of the tent show of Doctor Mirakle and in certain street scenes and in Camille’s bedroom ...which many others would have refused to do... Understanding what I wanted, he was a great help in getting it on the screen.”

Freund’s trademark mobile camera was almost perpetually on the move, in a manner reminiscent of his virtuoso work on The Last Laugh. It followed Camille’s movements back and forth on a swing; panned from Mirakle in the street up to Dupin and Camille embracing on a balcony and back down again; crossed Lugosi’s laboratory to reveal his gruesome experiments first glimpsed in silhouette.

However, it would be a mistake to attribute lone credit to Freund (as some have) for the heavy use of expressionism in Rue Morgue. In contrast, Dracula, also from a script by Garrett Fort, is only occasionally successful in overcoming the stage origins of the source material. Shot almost exactly a year earlier, it contains almost no expressionist elements, despite Freund having served as cinematographer. By comparison to Dracula, the Germanic influence in Rue Morgue is prominent throughout all aspects, from plot to set design to photography. Because of the style’s pervasive presence, as well as its frequent appearance in Florey’s previous and subsequent works, Florey must be regarded as having more impact than Freund on The Rue Morgue. What was unique about Rue Morgue was that in Florey and Freund it had a unique team, a perfect fusion of mutually inspirational artists whose combined skills led toward the creation of an expressionist masterpiece in the Hollywood climate.

Florey recalled having his hands full on the production of Rue Morgue, Freund could be “over-particular and unreasonable.” Leon Ames added that Florey and Freund “would complain about the producer, Eph Asher,” and that “Florey was always under pressure from the front office, which bugged him.” The performers could be no less difficult; Florey had to try and rein in Lugosi’s tendency to chew the scenery, while Ames (then still using his real Dutch name, Leon Waycoff), was making a screen debut from the stage.

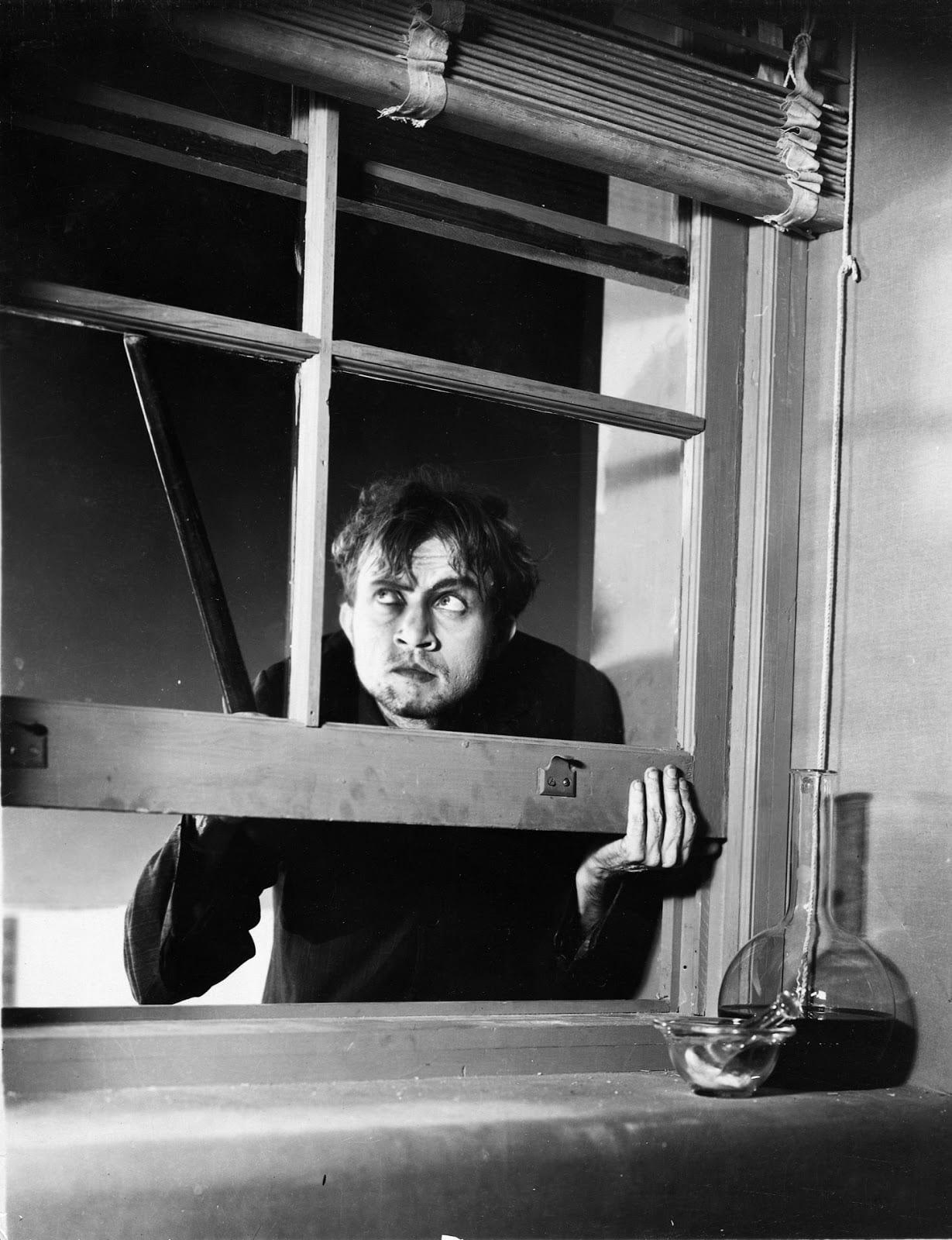

The acting was in a different vein from the Hollywood norm of naturalism and contemporaneity, striving instead to accent the period setting and fantastic nature of the story through florid, stereotypical characterizations compatible with the bizarre set design and expressionistic camerawork. For the simian role, close ups were obtained from two days of photographing a resident of the old Selig Zoo on Mission Road. Only in the long shots did Charles Gemora, a diminutive Filipino sculptor, appear in costume, but even then actual close shots were constantly interspersed. The gorilla’s stunts were done by the famed strongman Joe Bonomo.

Shooting lasted 23 days, from October 19 through November 13, 1931, going five days over schedule but remaining under budget. This included much night work, climbing over rooftops in what Leon Ames described as chilling cold, sometimes until 3 a.m. — with no place to rest and at most a few sandwiches brought in, followed by a 7:00 a.m. call the next day. However, just as Rue Morgue was completed, Frankenstein went into release, and its enormous grosses convinced the studio to spend another $23,178.14 for seven days of re-takes and added scenes from December 10-19, bringing the total cost of the film to $190,099.45. By contrast, Dracula was shot over 44 days for $341,991.20. Frankenstein cost $291,129.13, and shooting lasted 35 days.

The two pictures were made almost back-to-back, Frankenstein being completed October 3 and Rue Morgue commencing 12 working days later. Being shot with such proximity, there was no time for the Murders In The Rue Morgue team to learn from its predecessor, yet from a cinematic standpoint, Rue Morgue was in some ways a tremendous improvement over Frankenstein. The work of Florey and Freund was especially advanced in terms of camera mobility and the effective utilization of sound.

Since Universal had originally intended Florey and Freund for Frankenstein, and because of the continuity Florey wrote and the test he directed, it is possible and valid to speculate on what their Frankenstein might have been like and how it would have differed from the existing version. As the original continuity and test demonstrated, a Florey/Freund Frankenstein would have used the moving camera as an expressionist device, with numerous bizarre camera angles and compositions, as well as mysterioso lighting. There were also to be dozens of shots composed in depth: Florey frequently noted his plans for using 25mm and other wide-angle lenses. Nearly all the shots planned for the moving camera, particularly to give dimension or develop a distinctive long take, were eliminated by Whale, and he added few such flourishes of his own. Yet he kept most of the expressionistic set design derived from the sketches Florey and Hall collaborated on, even though Whale’s uncertain use of camera effects sometimes prevented this element from integrating purposefully in the film - as it would so vitally in Rue Morgue.

assistant director Charles Gould.

Later horror films, at Universal and elsewhere (including those directed by Whale), owe more to the example of Rue Morgue than to Frankenstein. This is true both in terms of content, because of Florey’s role in the authorship of both scripts, and to an even greater extent in the visual style, Florey and Freund enunciated in Rue Morgue. Yet Rue Morgue has never won the popularity or following of Frankenstein, either in its own time or in subsequent years, this in spite of the fact that it sums up at once what had gone before in the genre (chiefly through its meticulous use of expressionistic techniques derived from the German cinema of the 1920s), and at the same time looks toward future narrative developments (especially films in which the attempt to manipulate or mutate nature leads to her revolt against mankind).

It was, and remains, in many ways, utterly unique: none of the Universal horror films were so redolent of European filmmaking techniques, in terms of narrative, visual design, lighting, camera technique, exaggerated acting, and deliberate pacing; there was little of the characteristic gloss or unobtrusive style of Hollywood studio production. The differences from the norm of American filmmaking were made especially apparent by the various “remakes.”

The 1932 Rue Morgue was the product of a one-of-a-kind, one-time-only collaboration. In Florey, it had a writer-director who was already deeply concerned with integrating the artistry of the European film into the Hollywood feature. Cinematographer Karl Freund was one of the most innovative cameramen of the time and the world’s leading exponent of the art of expressionist photography, especially as it related to the thriller.

Florey and Freund were never again simultaneously at the same studio, so Rue Morgue remained their sole collaboration; this was doubly unfortunate since in later years each eagerly devoted much-unfulfilled effort to making a musical based on the life of Jacques Offenbach, for which Florey had even written a treatment. However, in 1951 their careers coincided once more when both pioneered in the medium of filmed television and made vital contributions to its development, Freund photographing the multi-camera comedies of Desilu and Florey directing the award-winning dramas of the anthology show Four Star Playhouse.

For access to more than 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.