Into Battle on Mulan

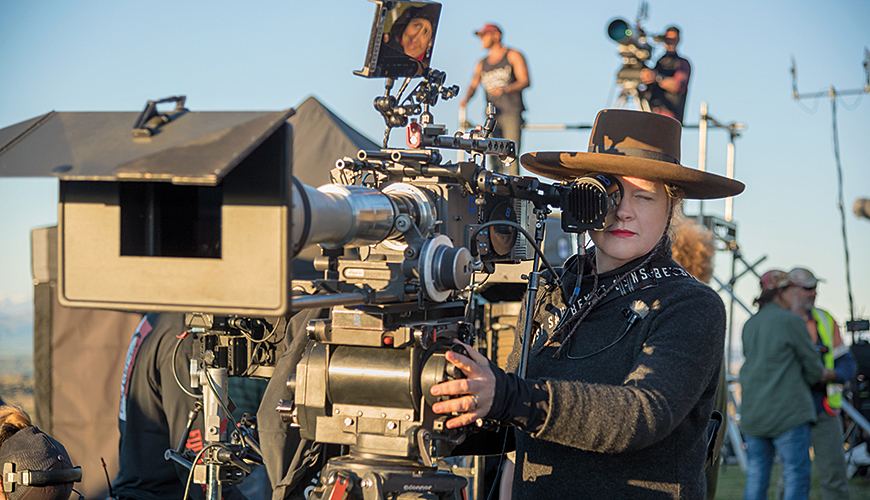

Cinematographer Mandy Walker, director Niki Caro and key collaborators detail the making of this period epic adventure.

By Ben Allen, ACS

Photos by Jasin Boland, SMPSP, courtesy of Disney Enterprises

This is an expanded version of the production story that appears in AC Sept. 2020.

“I believe that light is emotion,” observes Mandy Walker, ASC, ACS. It is an understanding that has grown throughout her career, which began in Australia as what was then a rare female cinematographer and has carried her to the very heart of Hollywood.

When director Niki Caro approached Walker to join her in making a new, live-action Mulan for Disney, Walker knew this could be a chance to do something special. “It is a very important film about a woman realizing her inner strength and power and gaining confidence in that,” explains Walker, “and it’s a Chinese story that works on an international level and it has a good message about family and culture and devotion.”

So here was an Australian cinematographer and a New Zealand director telling a traditional Chinese story, for an American studio and a global audience. In other words, a very 21st century production.

Producer Jason Reed explains, “We set out to make a film that honors both the original [Chinese poem] ‘Ballad of Mulan,’ and the rich tradition of Disney storytelling.”

“It’s a really emotional film and it has great life lessons of being loyal, brave and true and I am proud that what we achieved was special.”

Walker and Caro began by spending a whole day at the iconic Arcana bookstore in Los Angeles, leafing through books of Chinese art. In the process they began to find clues to a refined color palette and symmetrical composition that would end up contributing dramatically to the distinctive look of Mulan. Other sources of inspiration flowed from Chinese focussed cinema, particularly the films of Zhang Yimou including Hero, Ju Douand Raise The Red Lantern along with other great cinematic epics such as Lawrence Of Arabia. “Niki would tell me how she sees the story and how she sees the emotional journey of the character. I would glean little notes and expressions from her about scenes or how she wants the audience to feel or how Mulan is feeling and I start from there.”

“We kept returning to the Chinese art references,” Caro explains. “All of our framing is driven by the things we recognized in Chinese painting and then the lensing — the colors and the softness that you see in ancient Chinese art and the deep background and the beauty. Always the beauty.”

Lawrence Of Arabia — photographed by Freddie Young, BSC in 65mm Super Panavision 70 and directed by David Lean — was another reference. “It’s beautifully shot,” confirms Walker. “They used [the attributes of] 65mm for the epic landscapes and then also the tight intimacy of close-ups. Some people ask, ‘Why would you use 65mm when you’re on a close-up in a little tiny room?’ But the format gives you something else. You can be on a wider lens and separate the foreground from the background. So you can be on a 50mm or a 40mm, which we used a lot, for a mid-shot or even a head-to-toe shot of somebody and I can separate the background from the foreground. You have a wider shot with the same depth of field as a mid-shot. That’s a beautiful thing.”

But could Mulan be shot on 65mm film? Although Walker loves returning to shooting film — as she did for Hidden Figures — it was never a consideration for this project. “For what Niki explained about how she wanted to cover the tighter shots, 65mm was the perfect option, but to shoot 65mm film in New Zealand, where there’s no lab… It would have been a huge turnaround on dailies.”

Walker knew that the Arri Alexa 65 would give her the sense of scale and the filmic 65mm look they wanted while meeting the practical needs of a production on this scale. “I used the Alexa 65 on The Mountain Between Us and thought it was a great landscape camera. I’m really happy with the images that you can get on 65 digital.”

Reed was also enthusiastic about the 65mm format “I always thought of the film as Lean meets Kurosawa as told by Zhang Yimou — so when Mandy and Niki decided the film needed to be shot with the 65mm sensor, I got very excited.”

A-Camera 1st AC Brenden Holster found the Alexa 65 to be practical as well. “The best thing about it — aside from the sensor size and the benefits that brings — is the fact that it’s a true production camera,” he explains. “It’s easy to use handheld, Steadicam, crane, tracking vehicle and, performance wise, it’s extremely solid. No lost data, no downtime for technical problems. I worked on one of the first features to use the 65 back in 2015 and Arri has extended its capabilities greatly since then while still keeping everything so simple.”

At 54.12mm across, the image sensor of the Alexa 65 is 50% wider again than 8-perf VistaVision and more than twice as wide as Super 35, making it the widest sensor currently available to cinematographers and the only one that accurately recreates the perspective of 65mm film.

Having inspired their choice of the 65mm frame, Young and David Lean’s masterpiece had one more creative gift in store for Walker and Caro, courtesy of ASC associate member Dan Sasaki, senior vice president of optical engineering at Panavision. The cinematographer notes: “He’s this brilliant technician, but you can also talk to him about the emotion that you want to create with the image. I did lens tests at Panavision for two days and Niki came in as well.”

For Walker, the choice of lenses has a creative significance beyond even the choice of camera and as she tested the variety of different vintage and modern lenses at Panavision she began to hone in on the characteristics they needed for Mulan: “We ended up with the Sphero 65 lenses, which are built from the actual Lawrence Of Arabia lenses. I de-tuned them even more around the edges to add little bit of softness into the image and sometimes a vignette.”

This capacity to access historic lenses from Panavision’s vast inventory — combined with Sasaki’s ability to modify them for specific needs — enabled Walker to define the precise tools she needed.

She also chose two of Panavision’s special portrait lenses, a Petzval which she used for Mulan’s close ups in emotional moments and a Guass lens for her moments of strength and power. The softness at the edges of these lenses worked particularly well because they had decided to favor center framing for the character of Mulan, as this was one of the stylistic elements they had drawn from the use of symmetry that is so prominent in Chinese art. Explains Caro “It was a core principle of this movie that Mulan is at the center of it all. She’s not going to be side-lined in any fighting. She’s not going to be stuck on the side-lines by any male character. She is going to be the center. It’s also beautiful and it never meant I compromised anything in the cutting room at all.”

After choosing their camera and lenses, many cinematographers now find that their choice of LUT is the next most significant one. The Look Up Table, which is applied to the camera’s output to deliver a more finished looking image on set, in dailies and in editorial, without diminishing the latitude of the RAW image being recorded, has many implications for the creative process. Walker wields this as another powerful tool in creating the right visual style for Mulan, and on each digitally photographed film she does, she creates at least one custom LUT with the characteristics required for that story. Walker explains, “After I’d selected the lenses, we did some testing and created a LUT based on Arri’s K1S1, but I wanted a little more latitude in the shadows so we made it slightly darker than K1S1. This meant I knew that if the image looked normal, I would have about half a stop more detail in the shadows of the RAW image. The red was also a little more saturated, so it popped but it was really quite subtle.”

This subtlety and simplicity in the LUT has become an integral part of Walker’s approach to working with digital: “I used to have a LUT for night, a LUT for day, a LUT for this and a LUT for that and then I find I’m always changing it in the CDL on set anyway.” The ASC’s Color Decision List format allows primary color corrections to be done on set and for these decisions to stay with the images for dailies and editorial. “Now I’m trying to be even more basic with my LUTs, I’m designing the parameters of what we’re going to be doing and then it’s like shooting film. You have a negative that you’re familiar with and you know that if you’re deviating from that base with a strong CDL you get off track and you start skewing the image. It’s hard to come back from that because it affects other parts of the image. You get into a place where you have to adjust it too much to get it to where you want. Instead, I try to do as much in camera as I can.”

On-set color decisions were made by Walker and implemented by DIT Christopher Rudkin to the CDL format and then the CDL was applied to create graded dailies by Rebel Fleet, delivered using the Moxion system to be instantly available to the appropriate people, anywhere in the world.

Despite having a blockbuster budget, the ambitious scope of the film meant that Walker and Caro had to draw on all of their experience making both big and small films. “For a film of this size,” says Walker, “we had a pretty short schedule, just 74 days, so we had to work fast.” Caro goes on to explain, “Mandy and Liz Tan [1st Assistant Director] and I were really well prepared and we made sure everyone was communicating, so we made our days, came in on schedule and slightly under budget.”

A big part of Walker’s strategy in making this happen was to make sure that lighting could achieve the right look without becoming a bottleneck for time. “I brought in [gaffer] Shaun Conway because I’d worked with him a lot and knew we could be prepared to look any direction without having to say, ‘We have to to take time relight the whole set.’ He had multiple soft boxes pre rigged that we could adjust through the dimmer board and minutes later we’d be ready to shoot.”

Conway elaborates: “The soft boxes are 8'x8' custom-built boxes. I can put them in any configuration to fit the set. They are all LED-based — some use Arri S60 Skypanels, some are BBS Area 48 Color and others are Area 48 Bi Color. I use them for different purposes with different lamps or I match them all up for a particular scene. They are lightweight, punchy, and can be used as an ambient level, lowered and angled for a key, and used on stage and out on location as an overhead, fill or key. And their size is not restrictive. I can lower them from the gantry straight onto carts and roll to the next set ready for rigging. Plug in one low-amperage power cable and we’re ready to go.” They also enabled Walker to work at a base stop of at least T4, even on massive studio sets such as the emperor’s throne room.

Another key element of Walker’s approach to shooting fast was to generally keep the A-camera on a 45' Scorpio crane with an Oculus remote head: “A-Camera operator Jason Ellson, who I’ve worked with on about five films, is based in the U.S., but he’s Australian so he could come over with me to New Zealand and he’s a very talented operator.”

“[Using a remote head] saves a lot of time and it means you’re not laying track all the time. We could also easily adjust the shot to be starting high and coming down low or whatever we needed it to be.”

The telescoping arm of the Scorpio meant that Caro and Walker could execute their pre-planned shots efficiently but could also seize opportunities as they came up and remain creative and nimble on set. “It saves a lot of time and it means you’re not laying track all the time. We could also easily adjust the shot to be starting high and coming down low or whatever we needed it to be.” says Walker.

Key grip Jay Munro often also used the smaller 23' Scorpio for the B-camera, allowing both cameras to achieve complex moves and then reposition almost instantly. “It’s why I don’t operate on a film like this, because I can be there with the monitors standing right next to the director and orchestrating what we’re doing,” says Walker. “Sometimes on the second take, if we liked what one camera had already got, we would give them another job to do on the next take and it would be very efficient.”

When it came time to swing around and do reverses on a scene, Conway could raise one set of soft boxes out of shot and lower the required ones into position while the cranes could swing the cameras into place and the whole team would be ready to shoot in mere minutes. While this approach was relatively easy in the studio and on the backlot, the production also used some spectacular but inaccessible locations on the South Island of New Zealand. Munro and his team were determined to make the same techniques work out on location: “It presented a lot of challenges for equipment access, so I used helicopters to fly the gear often including the 45' crane. We would remove the arm from the base and get the pilots to land the arm on the base when in the location.”

The battle scenes presented their own stylistic challenge, and Caro decided to stay away from the frenetic visual approach commonly used in Western films. While employed to great effect in Gladiator and Game of Thrones, Walker describes it as “a melee of fighting and lots of swords crashing into one another.” Instead, the team favored precision and a dance-like, lyrical style that could be applied to everything from fight choreography to camera movement, which was also better suited to the Chinese aesthetic that inspired them.

The scenes in the family home were driven by softness and warmth and this stylistic choice was used to inform lighting and lens choices such as making special use of the Petzval lens for its unique softness. Walker explains that this philosophy particularly influenced her lighting in the home: “I wanted to keep that kind of soft, diffuse Chinese light and the warmth in the houses. Another thing that Niki said to me is that she really liked the lighting not getting in the way of the actors or the performance, so Sean’s soft boxes were especially good for that.”

Yet another set of choices was made to govern the look of the garrison at night. “The primary source was firelight there,” explains Walker. “We decided we didn’t want to do a hard moonlight. I would have the firelight as the main source of light and then we had smoke and I lit the smoke so the ambience would have the color of moonlight. So we’d have a run of 30 [8'x8'] soft boxes above for our big moonlight. Then we put five or six smaller ones down low to be the firelight. In the throne room and a couple of other locations, we lit through smoke with harder directional light to create drama.”

Walker also made use of a special 2800mm lens built by Sasaki and modified to work with the Alexa 65. “It’s huge,” says Walker. “The front element is about 10” wide. It only has three stops at T16, T22 and T32”. Holster and B-camera 1st AC Ben Rowsell both had to quickly become experts in the unusual lens. Holster explains further: “The 2800mm is a delicate balance photographically. We generally shot T22/32 split — any wider and resolving focus becomes extremely difficult, any deeper and you start to ‘see’ the interior of the lens because the front element is nearly 3' from the sensor. It also magnifies any dust or debris on the sensor itself, which is a challenge when working in dusty, dry exteriors such as the desert in China. We used the atmospheric conditions to great effect — heat haze, dust, mist can take on beautiful photographic qualities, and that is something Mandy is a real master at.”

Walker found the 2800mm particularly effective for battle scenes, as she could position it behind one army and shoot through it to the opposing side, dramatically compressing the space between them to heighten tension. “It’s really tricky for the focus pullers,” she says. “But once they all got into it and had a practice, they loved it. It was a challenge for them and I had such great crew in New Zealand”

Back in Los Angeles, the team settled into postproduction, and once Caro and editor David Coulson had a cut of the film ready for them, Walker and EFilm colorist Natasha Leonnet began two weeks of initial color grading. Although many of the visual effects shot were still in progress, they were able to establish the flow of look through the film as well as fine tuning many sequences. “I’ve worked with Natasha several times [including The Mountain Between Us and Hidden Figures]. She has a really good eye and a good sensibility,” says Walker. “Natasha’s also really good at involving us and making sure that she and Niki and I are all on the same page and that she’s giving us exactly what we want.”

In the DI theatre, Walker likes to do an initial pass to concentrate on the RGB balance and overall brightness, using the Printer Light Offset controls in DaVinci Resolve. These controls function like a traditional photochemical grade, with only four controls to manipulate red, green, blue, and “density” for all three together. It also produces a set of three printer light numbers corresponding to the RGB channels this makes it easy to keep track of the changes that have been made to each shot or sequence and make sure that the color balance and brightness of the basic grade is right before going into more detailed corrections and additions to the look. As with Walker’s discovery that simplicity has great value with a LUT, this phase of balancing the film using the most basic controls has become an essential strategy in getting the best results from digital. Leonnet explains: “This was the first film in which I got to use the RGB Printer Light balance on the Resolve and it was really elegant. Mandy’s images have so much latitude that it’s almost as though she’s shot on film. When you start using her images with printer lights, they just fall naturally into place and there’s a naturalism that comes from the RGB balance.”

Following this process reel by reel, they could then go back and finesse using the more complex tools of the DI including Power Windows to enhance what had already been done on set. This then became the basis of the grade that was used for test screenings and previews while work continued on the visual effects.

One of Caro’s early creative decisions about Mulanis that the film would be much more grounded in historical realism rather than the fantastical world of the 1998 animated film. “This made our collaboration with Niki and Mandy even more critical,” explains visual effects producer Diana Giorgiutti, whose other credits include Ant-Man and Spider-Man: Homecoming, “so that every shot could be seamless and lit in a way that would fit with the era. Not only do we hope the viewer will be transported back to China from the days of Mulan but we also hope that the audience will not notice that we’ve had our VFX hands in the film.”

These types of “hidden VFX” are becoming an increasingly important part of the production process, allowing dangerous stunts and situations to be captured with appropriate safety for the cast and crew or to override uncontrollable things including evidence of the modern world in backgrounds or inescapable weather. Reed explains from the producer’s perspective, that “we wanted to shoot as much of the film as practically as possible. Obviously, elements like weather, terrain, huge armies of horse cavalry, and locations with limited access, make it more complicated than simply shooting on stage, but Mandy’s deep understanding of how to integrate VFX and how to use all the tools provided in color timing, allowed us to mitigate the issues we encountered on location without compromising the quality of the film or our budget.”

Walker believes that working closely with the VFX team is an essential part of the DP’s job and this begins in prep. As she explains, “One of the very first things I always ask in preproduction is, please can you make sure the VFX vendors give us mattes [of the VFX layers] because it saves so much time in the DI and I’m not rotoscoping shots. They were great; we had a lot of mattes and it was fantastic. I work very closely with visual effects right from the beginning because we all have to be on the same page and I want to make sure they understand the visual language is that Niki and I have discussed and I understand how they’re going to collaborate.”

This active engagement with visual effects has earned Walker particular loyalty and support from the effects teams she works with. Giorgiutti notes, “She has our back and we have hers. Whether we planned ahead with Mandy on the look and lighting she wanted to achieve in a complex scene, or it was off the cuff when the weather was not playing along, having the open dialogue and transparency we had with Mandy, was key to our visual achievement. I believe the collaboration shows on the screen.”

By the time the final visual effects shots were coming in, Caro was supervising the sound mix at Disney and Walker was back in Australia in pre-production for director Baz Luhrmann’s upcoming untitled Elvis Presley biopic.

EFIlm’s VP of technology Joachim “JZ” Zell, who is also an associate member of the ASC, set up specially calibrated rooms at Disney for Caro and at Australia’s Cutting Edge postproduction for Walker. Zell details: “We need a sufficient data connection with a reliable 100 mbps, a digital cinema projector, a projection screen and a theater room, all meeting our specs and without silver screens, dirty screens, white or colored walls, colored seats or unwanted ambient lighting.” Once they found facilities that met these strict requirements, Zell could precisely calibrate the projection systems for digital cinema’s P3 color gamut, gamma of 2.6 and a white point of D65 (6500º Kelvin).

Using Nevion’s T-VIPS system, Caro and Walker were able to work with full-resolution pictures in real time while discussing the grade via speakerphone with Leonnet, who worked otherwise normally in EFilm’s Hollywood headquarters: “I’m just so grateful for that technology. It’s just flawless and I couldn’t have done this film without it.”

Because T-VIPS uses the same JPEG-2000 compression codec used in digital cinema DCPs, the pictures have the same color space and depth as a finished DCP, and yet Walker and Caro could see the images updating in real time, including Power Window shapes as Leonnet adjusted them. Walker would spend eight hours each Sunday looking at the work that Leonnet had done during the previous week and discussing the fine tuning which she could then implement as part of the week ahead. This allowed Caro to return to the sound mix and Walker to focus on pre-production for Luhrmann’s film during the week. “It was wild,” says Caro. “It made for a really great day at the office.”

Walker elaborates: “In the past, you would’ve just been sent some still images, but I was looking at exactly what they were looking at. The three of us were in different locations and watching it together. It’s mind-blowing.”

After completing the cinema version, Caro and Walker left it to Leonnet to complete the other deliverable iterations. “I would normally be there for the different versions,” Walker explains, “but I was able to leave it with Natasha to do the 3D versions, the Dolby Vision HDR versions and a Rec.709 version for normal TV. I can trust her with those tweaks because she’s been so involved all the way along.”

Looking back at the experience of making Mulan, Caro says, “Filmmaking intrinsically takes a gigantic amount of effort to create a believable world that an audience can live in for two hours and leave their own lives behind. Yet on this film, with all its epic nature, the work with Mandy was effortless.”

Reed elaborates: “The film would not be what it is were it not for the incredible relationship between Mandy, Niki and Liz Tan. The production plan was very ambitious, but the three of them worked together so efficiently, so seamlessly, that we were able to bring the movie in on schedule while still over-delivering on all the creative elements.”

Walker went onto the project with high expectations of working with Caro. “Niki has been one of my dream directors to work with ever since I saw Whale Rider,” the cinematographersays, “and this was a great experience. Despite the pace and scale of this film, there was no one yelling or running around like headless chickens! We were very organized and in control and we had fun. I think the decisions that we made along the way were right.”

For Walker, that meant being able to put Mulan’s story in exactly the right light: “It’s a really emotional film and it has great life lessons of being loyal, braveand true and I am proud that what we achieved was special.”