Lives Under Siege: The Goldfinch and 1917

Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC takes on contemporary drama and the depths of war.

The Goldfinch unit photography by Macall Polay; images courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment and Amazon Content Services.

1917 unit photography by François Duhamel, SMPSP, courtesy of Universal Pictures.

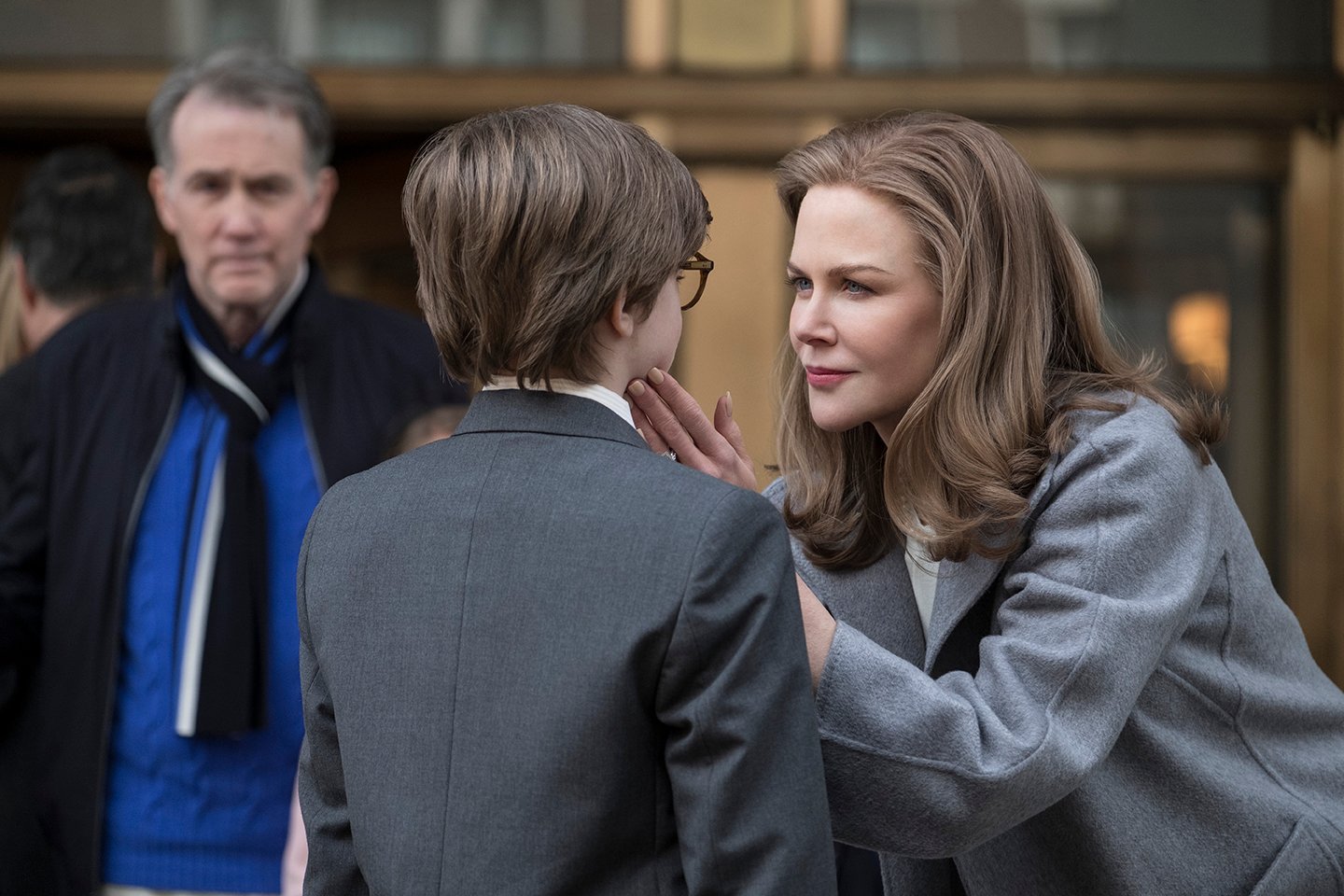

No two projects are alike for any cinematographer, but this year marked a particularly varied slate for Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC, who shot John Crowley’s contemporary drama The Goldfinch, released in September, and Sam Mendes’ period combat film 1917, released Christmas Day.

Adapted from the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Donna Tartt, The Goldfinch tells a story that spans two decades, following a boy who loses his mother in a bombing in Manhattan and contends with the effects as he evolves into adulthood. 1917 simulates a single, unbroken shot to follow two British soldiers taking an urgent message to the Western Front. The Goldfinch was Deakins’ first collaboration with Crowley, and 1917 was his fourth feature with Mendes, following Jarhead (AC Nov. ’05), Revolutionary Road (AC Jan. ’09) and Skyfall (AC Dec. ’12).

The cinematographer recently met with AC in New York to discuss both productions. His wife, James Ellis Deakins, was the digital-workflow consultant on the projects and provided additional details during the conversation.

American Cinematographer: Let’s begin with your approach to two scenes in The Goldfinch that bookend the relationship between Theo and Pippa, his love interest. In the first, they’re children [played by Oakes Fegley and Aimee Laurence], and he visits her in her room after the bombing. In the second, they’re adults [played by Ansel Elgort and Ashleigh Cummings] at a restaurant, and she tells him she doesn’t plan to return to New York.

Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC: That scene in Pippa’s room is a good example of how we approached location work in New York in general: We were shooting in winter, so daylight was short and inconsistent, and we basically had to take out the natural light and re-create it so we could get a 12-hour shooting day. That scene was shot on the second floor of a small townhouse in Bedford-Stuyvesant. John and I wanted this pastel light, motivated by the window blinds, and then to have the sun come out at a key moment in the scene. I needed to create a wide, soft source to mimic natural daylight whilst at the same time bypass the density and color changes that would occur as day went into night. [Gaffer] Steve Ramsey and his crew suspended a 20-by-20-foot Ultrabounce from a crane to cut out the natural daylight, and then we bounced an Arri M90 off that same rag to create some soft ambience. There was a second Ultrabounce, a 12-by-12, and another HMI bouncing off that. Another M90 was used to create a hard pattern of sunlight, and it was fitted with an electronic shutter so I could have the sun come out on cue. The set dresser and I chose some yellow blinds specifically for the scene, and the windows were covered with Hampshire diffusion. The diffusion allowed me to shoot at the windows after dark without seeing my rig, and it was so minimal it made little difference to the shaft of ‘sunlight.’

Their dinner as adults was actually shot in a bar in Albuquerque, New Mexico. We also filmed the scenes [set] in Las Vegas, where Theo goes to live with his father for a while, in Albuquerque. We scouted many restaurants in New York, but it worked out that we couldn’t shoot the scene there. In a way, that didn’t matter; that scene is all about character — it’s about the faces. We had the blocking in our heads, and we knew we just needed a bit of a view out the window in the background. Outside the window at the location, [production designer] K.K. Barrett built a bit of a New York street, including a few trees, and I spotted in two 2K Fresnels that were gelled with 1⁄2 CTO and on dimmers to create the feeling of street lighting. The restaurant interior was lit by the practical candles, with no supplemental lighting other than background practicals.

How did you create the surreal feel of the scene when Theo regains consciousness after the explosion?

It’s meant to reflect his memory of the event rather than the reality of it. We wanted him to wake up in this kind of void, an otherworldly landscape. We built the museum interior in a warehouse in Yonkers, shot the scenes that preceded the bombing, and then basically decomposed the set and filled it with smoke and dust. We created a series of oblong rigs, containing 50 or 60 Arri SkyPanels in total, recessed in the ceiling, so I could completely control both the color and the light level. I dimmed the lights nearer to the camera down and made the lights in the distance brighter so I could get more of a silhouette, a backlit feel, and the lights farther back would blow out the smoke a bit. The light has some shape to it; it isn’t a flat gray.

How did you shoot Theo’s approach to, and dialogue with, the dying man in that scene?

Some of that was on a Technocrane with a remote head, and some was a Steadicam move circling Theo. There’s the faintest image in the background, so you hardly know you’re moving.

How did you develop the recurring image of Theo’s last memory of his mother, where she takes her hand from his shoulder and walks out of focus?

John and I talked about our own memories of childhood, and we agreed that it would be details Theo remembered, not a clear picture of the whole event. The shot of Theo’s mother’s hand as she leaves her son for the last time was made on a 50mm [Arri/Zeiss Master Prime] that was wide open. I felt a longer lens gave too much fall-off and seemed less connected to the subject, whilst a wider lens gave too little fall-off. The shot worked best with the 50mm when [1st AC] Andy Harris pulled focus in opposition to the receding figure. We wanted to keep the backgrounds out to emphasize the otherworldliness of the moment. When Theo comes out of the museum after the explosion, we continue that idea by staying quite tight on him, making all the people fleeing behind him slightly out of focus. It’s quite effective, I think.

When Theo and Boris [Aneurin Barnard] reconnect as adults, there’s a long dialogue in the car when Boris makes a surprising confession. Was that poor-man’s process?

Yes. We actually shot that scene out on the street first, but John decided to reshoot it as an interior and have Ansel jump out of the car at the end. We shot plates in New York and actually shot the actors in the car onstage in Albuquerque. To suggest the passing streetlights and shop windows, we programmed a chasing-light pattern with Color Force LED strips arranged in 60-foot rows on either side of the car. I’d used that approach to suggest spaceship travel in Blade Runner 2049 [AC Dec. ’17], and I thought it would be perfect for this car rig. In the car, we put an [Arri] Alexa Mini on a small Scorpio head so I could give it a little movement. I like that because it has the slight feeling of handheld without being jarring; I like that control. We considered projecting the plates outside the car windows while we filmed the scene, but decided that wasn’t necessary. We shot without a bluescreen or greenscreen and only with the white Ultrabounce material that the LEDs were bouncing off outside the windows. That made the rotoscoping of the characters and the car from the backing difficult, but it allowed for a far more naturalistic look, as the light was coming from where it was supposed to be coming from and wasn’t interrupted by a bluescreen.

We see the apartment home of the Barbours, the family that takes Theo in after his mother’s death, over a period of many years. How did you approach those scenes and establish a consistent feel?

The idea was to suggest fading wealth, a family that’s sort of falling apart. I wanted a gray, soft light, a somber feel. We had about four weeks of work in that apartment, and after scouting locations on Fifth and Park avenues, we decided to use them only for reference and to create the apartment interior in a house upstate in Rye. That gave us complete control over the light and the décor, which was a real advantage. It was basically a standing set that we could re-dress and decorate however we wanted, and I could surround the house with several 20-by-20 Ultrabounce reflectors, creating a seamless surround of soft bounce light whilst at the same time taking out all interference from the shifting natural daylight. The reflectors were rigged at an angle to the windows and therefore quite close in, so we used an array of smaller lamps to light them — Arri 4K PARs, 6K PARs and M90s — rather than a few large units.

You’ve said that from project to project, you seldom alter the LUT you developed for the Alexa some years ago with EFilm. Was that true of this movie as well?

Yes. We always take a look at it at the beginning of prep, and we usually like what we see. We used the same LUT on 1917.

Where did you do the final color grade on The Goldfinch?

At EFilm with my longtime colorist, [ASC associate] Mitch Paulson.

Turning to 1917, how did you react to the concept of telling the whole story in one shot?

When I saw ‘This is envisioned as a single shot’ written across the top of the script, I was a bit skeptical, I have to say. I thought it might come across as a gimmick. But then I read the script and realized what Sam was intending by the one-shot idea. He wanted the film to be immersive, to make the audience feel the urgency of the soldiers’ journey by staying with them every step of the way.

The film has a lot of day-exterior work, so I knew that shooting under cloud cover would be key to matching all the footage. Also, because the camera would often be doing 360-degree moves, there was nowhere to place any lights or lighting equipment. I was really worried about getting the right type of weather because just the year before in the U.K., there wasn’t a cloud in the sky for months. But it just happened that during our shoot, which was April 1 to mid-July, it was quite cloudy. We were very lucky. When the sun came out, we’d rehearse and rehearse, and as soon as we had cloud cover, we would shoot.

Of course, the idea of making a film in one continuous shot would not suit every film, or even many films, but for 1917 it seemed perfect — and also a wonderful creative challenge. As with any film, the choice of where to place the camera at any particular point in the story is crucial to how the audience will perceive that story. The challenge for us was to do that, and combine all those individual moments in a way that seemed totally organic. It was important that the viewer wasn’t left wanting a reaction shot or a wide shot, which are so very easy to incorporate into a scene when you can simply cut!

Where did you shoot?

We were based at Shepperton Studios and built one large set on the backlot there, but everything else was location. We dug about a half-mile of trenches at Bovingdon Airfield, and we shot a lot on Salisbury Plain, a huge military testing site that is mostly untouched grassland. It had the upland-chalk landscape [that was] very much a match to the Somme battlefields, and was exactly what we needed. Luckily, the military embraced our project. Sometimes they had shelling practice while we were shooting, and we could hear their explosions while we were staging our own, and we could sometimes even see them exploding across the valley. That was quite bizarre, really. We also shot some scenes in Glasgow and North Yorkshire.

We understand Arri provided you with prototype Alexa Mini LF cameras. What made you decide a large format was the way to go?

A slightly larger format gives you an image with a little less focus, a little less depth [for the same equivalent angle of view compared to a Super 35mm-sized sensor], and I liked that idea because stills from the First World War have that quality. One photo I found of English soldiers digging a trench was particularly interesting. One of them is looking at the camera, and I felt that the look on that boy’s face said it all. The actual framing and depth of field also seemed to be where we wanted to be. I had shot a lot of tests with the standard LF camera and with [Arri] Signature Primes, so as soon as I signed onto this film, I started talking to [Arri managing director and ASC associate] Franz Kraus, who has always been very supportive. I said, ‘Surely you’re going to make a Mini LF at some point.’ His initial reaction was, ‘Oh, dear.’ [Laughs.] But I kept asking over the next few months, and eventually he said, ‘When will you need it?’ I said, ‘We start testing in February [2019].’ He guaranteed we’d have it by then, and sure enough, they delivered the first prototype to us on February 18. We received two more about a week before we started shooting. Arri really came through for us. We were testing the cameras in pretty extreme conditions, and they were almost flawless. We couldn’t have shot the film without them, at least not the way I wanted. Key to it all was the size and weight of the Mini LF. Working with the stabilized systems we needed, and because we were traveling over such long distances, a lightweight camera was a necessity. I mean, you could not have done anything like this with any film camera.

How did you and Mendes approach shot design?

Preproduction was quite complex because nothing could be designed or built until we determined what we should show the audience and where the camera would be for each scene. When a soldier is walking, are we behind him or leading him? If we’re behind him, how far ahead of him do we see? If he’s approaching a town, what will we see in the distance, where is it on the set, and how long will it take him to get there? We storyboarded the entire script in a very rough way, and then we started rehearsing with the actors at Bovingdon, without a set, to figure out the timing. For instance, we’d mark out a trench line and have the actors [George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman] walk it, play the action and run dialogue with stand-ins, and then we’d figure out how long the trench needed to be to facilitate that. Then we shot another rehearsal with a little point-and-shoot camera that mimicked the LF frame. Once we knew precisely what the set had to be, [production designer] Dennis Gassner and his crew could get to work.

How did you approach shooting in the trenches?

We tested nearly everything. We considered a wire-cam and a remote-controlled rig on a rail for the trench work, but they didn’t feel human to me; they felt too disconnected from the actor. We tested a stabilized backpack rig that worked really well, but it limited us to that one particular angle. Then Pete Cavaciuti, my Steadicam operator, suggested he could develop a rig using the Stabileye that would achieve what we wanted. He worked with the company Optical Support and came up with the Dragonfly, which is basically a Steadicam-type arm with a post supporting the Stabileye. We found that was the most stable way to get fast movements in trenches; Pete could literally run down the trench with the camera pointing backwards, get to a corner and then pan his body to put himself in exactly the right place. We actually did shots that were a lot longer than I thought we could do because Pete was so good at it. We also shot some trench work with Arri’s Trinity, a stabilized rig that can arm up and down about 6 feet. The operator, Charlie Rizek, had never worked on a feature film before, and he was brilliant. I met him at Arri London when he demonstrated the Trinity for us. After he did it a few times, I said, ‘Can you work on this movie?’ He nearly fell over. [Laughs.] He was great. The trenches were muddy, so it was just a matter of figuring out how Charlie could keep his footing and balance the weight of the rig. We used the Trinity outside the trenches quite a bit as well.

What else did you use to accomplish moves outside the trenches?

A lot of it, probably most of it, was the Stabileye carried by [key grip] Gary Hymns and [A-camera grip] Malcolm McGilchrist. We also had a 50-foot Technocrane and a tracking vehicle with a 22-foot Techno and Libra head. We did some Steadicam work, a couple of big shots with the Stabileye on a wire, one short segment with a drone, and one scene with a Libra head mounted on a motorbike. We used an electric tracking vehicle and built a ‘road’ to track a 22-foot Techno on a camera car beside a slalom run in a water park. In prep, we shot rehearsals with some of the equipment we were going to use, even to the extent of testing a three-point wire rig to track a character across a river. By the first day of the shoot, we had a master plan of every shot and every item of equipment we’d use on that shot. I think there was only one occasion when we had to change tack, and that was purely because the wind was too strong on that day.

There are some very intricate takes that involve several [different] methods and multiple handoffs, and each was an amazing ballet of grips. Take lengths were up to 81⁄2 minutes. One particularly challenging shot starts on a 50-foot Technocrane with the camera on a Mini Libra mounted to a bar that is hanging off the end of the crane. The camera comes down into a trench, booms up with the actor [MacKay] to a point at which two grips then take the bar off the Techno and start walking backwards with the actor; then the grips hook the bar onto a second 22-foot Techno that’s rigged on a tracking vehicle on the other side of the trench. The vehicle then takes off as the actor starts running at full speed through a developing battle. Incidentally, the two grips are dressed like British soldiers so they can cross camera and look like part of the action. The tracking vehicle goes on for over a quarter of a mile, and at the end, the camera booms out with the actor as he runs back down into the trench. Meanwhile, explosions are going off, and dozens of extras are running around. I was operating remotely from a quarter of a mile away, and Andy Harris was pulling focus in another caravan, sweating. [Laughs] When we got to the end of a take like that and everyone had done their bit in sync, it was a real high. I don’t think I’ve ever had such a high. What added to the pressure was that often we’d only get a short window of cloud, and we’d have to judge whether it would last long enough for us to finish a take. I felt like I was operating with one eye and watching the sky with the other!

How was your operating setup configured?

I sat in a tent with [digital-imaging technician] Josh Gollish and James. I was operating off Josh’s [24-inch] screen, so I was looking at a calibrated image. Often I was using the wheels and pulling stop because there was a hell of a lot of stop-pulling. If we were operating on the Trinity, I would do the tilt remotely, so sometimes I was doing that and pulling stop. If it was Pete on Steadicam, I was just pulling stop. If it was the Stabileye, then Josh would pull stop while I gave him direction, and James would direct the grips over the radio while I looked at the screen and gave cues.

James Ellis Deakins: Given the distances involved and the complexity of the work, connectivity was a real concern. Preston [Cinema Systems] sent Noodles [aka Greg Johnson of RF Film] over to build custom radios to boost the signal for our Preston FI+Z system.

How did you determine camera position relative to the actor — for example, whether to follow, lead or track alongside at a given moment?

Roger Deakins: We always wanted to feel connected to the characters. Obviously, we had no option to cut to a reaction, so if we had to see a reaction, we had to justify that move and find the optimal place to start so we could build the move into the choreography of the action. In prep we looked at Son of Saul [AC Jan. ’16], which does a lot of long shots from behind the character, and while that was inspirational, it also taught us that we didn’t want to stay that long on the actor’s back unless there was something significant going on in front of him. Sometimes there was. Of course, how the individual shots were to be combined was of great concern, and we spent a lot of time considering how to make our blends; much time was needed on set to rehearse those moments. Playback was used to aid us in the matching of an actor’s position and the speed of a camera move on the A to B sides of the sequence.

The one-shot concept suggests you used just one focal length.

Two, actually. I used a 40mm Signature Prime for everything but a couple of interiors. I went to a 35mm in the tunnels and bunkers because I wanted to accentuate the claustrophobic feeling by going slightly wider — I wanted that sense of the walls. But you don’t really notice this in the transitions because the camera moves inside at those moments.

Did you do much image stabilization in post?

Some, but it was minimal and far less than I imagined might be needed when we began prep. We allowed a very small surround to our image size to facilitate this.

How did you light the bunkers and tunnels?

In the bunker where Schofield [MacKay] and Blake [Chapman] get their orders, we dummied the period lamps with 500-watt FEP bulbs dimmed down to about 23 percent, and the bulbs were also programmed to slowly pulse to give some feeling of a real flame. As the camera moved through the set, the bulbs were individually adjusted to allow for the camera’s change of angle. I had initially thought we might utilize a wire rig, with the camera being handed off and on twice, but Sam felt the Technocrane would give us a little more flexibility. So, we laid out a set plan using cardboard boxes and came up with a plan for the design of the set to accommodate this. After rehearsing with our cardboard set, we decided to do the shot with the Stabileye mounted on the 50-foot Techno and only one handoff. The Techno was set to the left side of the set, and the camera hung down through a gap in the ceiling. The set ceiling was constructed with a diagonal slit to accommodate the way the camera tracked, and [a] flap fell back to cover the slit once the camera had passed through.

When Schofield and Blake go into the tunnel, the flashlights clipped to their waistcoats light the scene. We dummied those with little LED units created by our gaffer, Biggles [aka John Higgins]. The LED was projected through a small lens, and we sandblasted the edges of this lens to get the desired beam effect. We wanted to see just enough, not too much.

How did you light the night exterior that’s illuminated by the burning church?

We built that set on the back lot at Shepperton, and we had to create an interactive-lighting rig that would be replaced by a CG burning church in post. This was a similar approach to one I had used for scenes in Jarhead and Skyfall, so Sam was quite familiar with the idea. The flames from the church are the only source apart from a few military flares, and the rig had to be 360 degrees to accommodate camera moves all around the town square. We built a six-tier rig that was about 50 feet tall using Maxi-Brutes, 12-lights, Nine-lights and Six-lights. Everything was on a dimmer, and we programmed a pattern that gave me patches of brighter light in areas where I needed more punch to focus on specific pieces of action or reach into an interior. [Dimmer-board operator] Steve Mathie could play with light levels as the scene developed; if I was looking at the rig, he’d bring it down, and if I came around and tracked with the actors, he’d bring it up as the camera hooked around. We needed quiet nights with very gentle breezes to film that scene because we had to add a lot of smoke, and much to my surprise, that’s exactly what we got. The weather was perfect.

What recording medium did the prototype Mini LFs use, and how did shooting with prototypes impact your workflow?

James Ellis Deakins: We recorded to Sony [SxS Pro Plus] cards. We were shooting [ArriRaw 4.5K] Open Gate, and we got about 28 minutes of recording time per card. In prep I spent a lot of time getting software updates for various systems because they wouldn’t recognize the camera. For instance, we needed an update for the Colorfront OSD [On-Set Dailies] software, and we had to change our original choice for deBayering software because Colorfront was able to provide updated software first. But our [HD] dailies workflow was smooth. I recommended we use EFilm’s EVue system as a secure way for editorial to send their proposed blends to Sam, and he could view them at a good resolution. Roger and I had an EVue setup in our home as well, and I also screened dailies every morning at Company 3 in London. We had an excellent dailies timer there, James Slattery. The workflow of the dailies was basically the same as on other films except for the fact that we would diligently check that the timing worked across the shots with a continuity of look.

Roger Deakins: Because of the one-shot concept, it was crucial that the dailies be even.

James Ellis Deakins: And they were. Roger was shooting what he wanted to see, so [the grading] was often just a slight density correction. James, our dailies timer, really got that. We tried to get a jump on the final grade by timing the picture with hard cuts, and now that all the blends are in place, we’re on our way back to London to finish up that work with [colorist] Greg Fisher at Company 3 on a Resolve. Basically, we have the dailies timing on each separate shot, and in the final grade we need to blend one shot with another. There is some effects work involved in this blending, but the work has been done without baking in any color, so we have the full breadth of the raw file.

Roger Deakins: It’s gone smoothly so far. It’s not a film with a huge amount of timing because what we see is basically what we shot, but it’s the details that take the time.

Given that so much was precisely planned, were there any moments of spontaneity or happy accidents?

While we were on Salisbury Plain, there was one shot where I wanted the sun to come out at the end of a certain scene that involved some lengthy dialogue. I was checking all my weather apps, and one said a front was coming in, but we waited for hours, and we couldn’t see anything in the sky down to the west, where the weather was coming from. Then one little, flat cloud appeared on the horizon, and I said to the AD, ‘Let’s get ready.’ We got it together; it was a really complicated piece of acting, with Charlie Rizek on the Trinity. We did the scene, and at just the right point, the sun came out. It was Take 1, and it’s in the movie — maybe only because it’s the best performance, but it was my luck that it was!