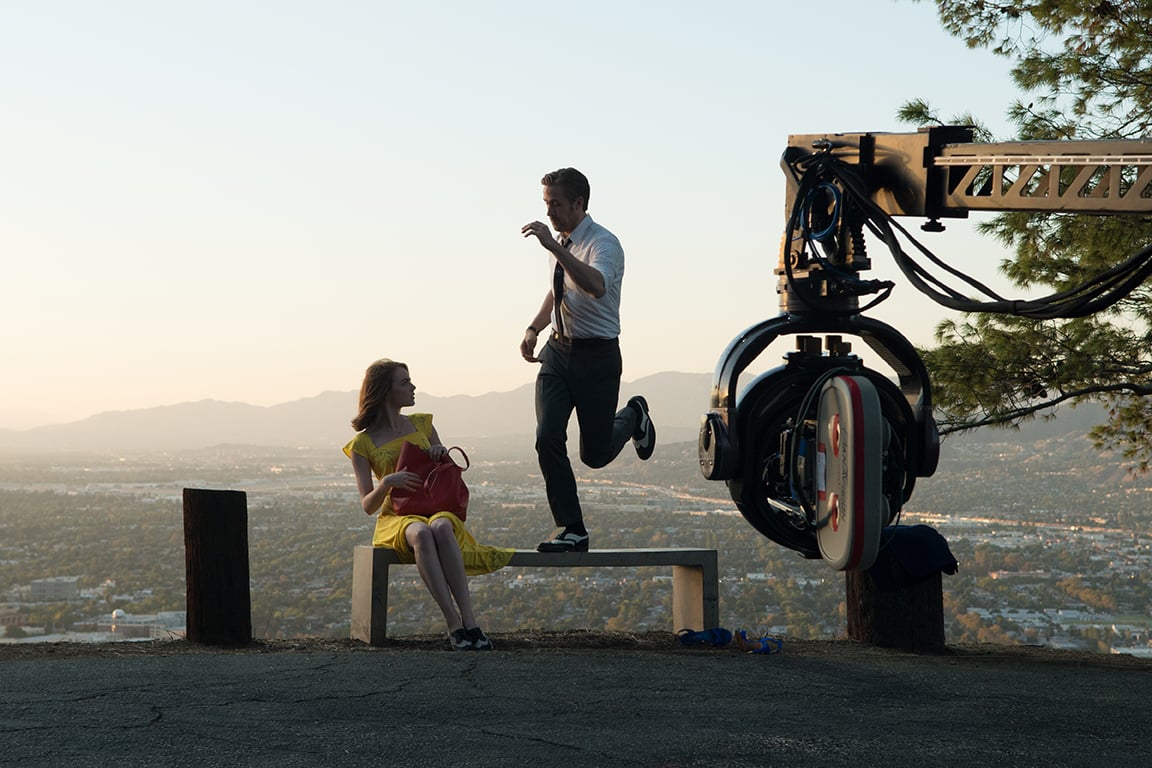

La La Land: City of Stars

Linus Sandgren, FSF infuses Los Angeles with heightened reality and a colorful glow in writer-director Damien Chazelle's musical throwback.

Unit photography by Dale Robinette. Additional photos by Linus Sandgren, FSF.

All images courtesy of Lionsgate.

Both romantic comedy-drama and homage to the golden age of the Hollywood musical, writer-director Damien Chazelle's La La Land is rooted in the present, yet imbued with a timeless quality.

As it opens, Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) and Mia (Emma Stone) meet confrontationally in a Los Angeles traffic jam and go their separate ways, not realizing how much they have in common. They are two among thousands of young L.A. denizens struggling to make it in showbiz. He’s a frustrated jazz pianist, talented but committed to a traditional style that can't earn him a living. She’s a barista and wannabe actress who can’t get beyond soul-crushing auditions and an alienating Hollywood scene.

They cross paths again when Mia is lured into a restaurant by an affecting musical performance. She finds Sebastian at the keys, submerged in a free-form jazz piece that's too off-script for his boss (J.K. Simmons). She wants to compliment him but he brushes her off. It takes one more chance meeting for a mutual attraction to emerge from beneath their bickering repartee, and it’s brought to life in the song-and-dance number "A Lovely Night." Romance blooms but gets complicated as R&B singer Keith (John Legend) persuades Sebastian to join his touring band the Messengers, and Mia makes one last play to jump-start her thespian dream. She and Sebastian come to realize that given the demands of their career goals and budding relationship, something's gotta give.

Chazelle, 30 at the time of filming, proved to be one of the industry's most exciting young talents with 2014’s Academy Award-winning Whiplash (shot by Sharone Meir) — also a music-themed project, though in essence a psychological drama. For La La Land he teamed with director of photography Linus Sandgren, FSF, appreciating the latter's work with director David O. Russell on American Hustle and Joy. They hit it off in their initial meeting.

"Damien is a strong storyteller, and he's very clear when he describes his vision," recalls Sandgren on the line from London, where he is shooting Lasse Hallström’s period fantasy The Nutcracker. "[Damien] is also a director with a big, romantic heart. I especially fell for his sincere love for classic cinema filmmaking, and for the original music for the film [by Justin Hurwitz, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul] that he played for me. I was surprised by the melancholic theme, and could immediately sense how this would impact the emotions of the story and make it a very different [kind of] musical.”

In a separate interview, Chazelle says, "One of the things I love most about Linus is that he has an old soul. He's in love with analog filmmaking, celluloid, Technicolor and old lenses. And yet he has this youthful energy and a tech-savvy brain that's all about finding new ways to do things. That epitomizes where I want this movie to live. I'm trying to hark back to certain old traditions but hopefully show you something you haven't seen before."

The director screened musicals for the crew to get them into the intended spirit. He cites influences from 1930s-1960s Hollywood, noting, "That tradition of musicals composed directly for the screen — where there's interplay among music, image, story, character and dance — was magical. La La Land started with this idea of taking that style of storytelling and applying it to a modern setting."

Particularly inspiring were French director Jacques Demy's 1960s-era The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (shot by Jean Rabier) and The Young Girls of Rochefort (shot by Ghislain Cloquet). "Even though they're completely heightened, magical movies,” Chazelle says, “they are resolutely stories about ordinary people, shot where they're set, and have this quality of real life that seeps through the artificiality of the genre."

During 10 weeks of preproduction together, Chazelle and Sandgren storyboarded and considered their approach. "Damien didn't want the film to feel like at first it's a realistic drama and then suddenly the characters break out into a magical dance number," Sandgren says.

Chazelle adds, "It should be like one continuous piece of music that flows from one state of being to another, and hopefully so seamlessly that you don't notice the gear shift. A lot of that burden fell on Linus' shoulders, because we decided early on that one of the key unifying things would be the camera, which needed a consistent personality, whether it was a musical number, a realistic scene or in-between. The length of takes, when the camera would move, and the color palette would stay consistent."

Sandgren suggests that Chazelle is more influenced by classic Hollywood aesthetics than by any particular film, guided by emotion in storytelling more than convention. "Some filmmakers of that time told their stories just the way they felt was right to tell it, and Damien has a lot of that," the cinematographer says. "He follows his own taste when deciding how to make a film. He might tell the story in one way and then suddenly take another turn. He doesn't necessarily follow any rules."

Forty-two days of principal photography began in August of 2015 in and around L.A. While they both now call the city home, East Coast native Chazelle and Stockholm-born Sandgren bring an outsider's point of view and found a shared aesthetic in terms of how they wanted to portray the iconic town.

"Damien wanted to show the blue nights and twilights of Los Angeles — maybe they're not always like that, but you might remember them that way — and those beautiful old gas-style streetlights from some parts of the city,” Sandgren says. “We also both loved Los Angeles' grittiness. Lincoln Boulevard might be considered ugly, but we love its telephone poles at magic hour.” He adds that production designer David Wasco, whose L.A. projects include Pulp Fiction, “shared his great knowledge of the city of Los Angeles, and presented his brilliant designs and visions for the sets with great passion, and we had a very tight collaboration on the colors of the film.”

The filmmakers made a concerted effort to shoot just before or after sunset for many exterior shots, such as when Sebastian, high on new love, walks alone on a pier; when the couple strolls together across a bridge; and when, toward the beginning of the film, they dance in the hills overlooking the city.

The latter sequence was captured in a single take at a location that Sandgren recalls finding on a first scout. “Having rehearsed and [blocked] the choreography of the dance and camera on the lot, [we were] now facing the reality,” the cinematographer says. “With a 300-foot [cliff] on one side of the road and a U-turn behind us, it seemed impossible to light at first sight and — being on a slope — very complicated to shoot. On top of this, [it had] to be shot in one single six-minute take at magic hour. In that moment it was quite a bit of stress, but [ultimately] I think that is part of the beauty of filmmaking — to reach these obstacles, lay them out as puzzles, and try to figure them out.” Chief lighting technician Brad Hazen, who has worked with Sandgren on commercials, “found a way to squeeze two condors along the slope just inches outside of frame left and frame right, and rigged them with LED lights,” Sandgren says. Down the hill for the beginning of the shot, they placed a 90K (15x6K) Bebee light. The production rehearsed the 27-mark crane move for the entire day, and shot five takes between 7 and 7:45 p.m. in order to get two takes with good magic-hour sky. They then returned the following day to shoot again during the same time period for a second set of takes.

The crew carried two cameras. Ari Robbins, another commercial collaborator of Sandgren’s, operated the A camera and Steadicam, while the cinematographer's frequent collaborator Davon Slininger operated the B camera and functioned as second-unit cinematographer. Only one camera was employed for musical numbers, as Chazelle wanted it to be evident that Gosling was actually playing the piano and that Stone was actually singing live.

"Damien wanted it to feel like we made a great effort to capture things without cheating," Sandgren explains. "The dance sequences were shot with one camera and the B camera might be off somewhere shooting a plate or another shot. We didn't shoot coverage in those cases. He didn't want to shoot anything other than what you see in the movie. Early in prep, we rehearsed the dance numbers in a dance studio or a parking lot [in collaboration with choreographer Mandy Moore] and later we rehearsed on location. We revisited frequently and recorded the rehearsals on iPhones, both for the camera and the crane positions to make sure we knew what we were going to do. Some scenes were rehearsed with full camera and crane equipment for days in advance."

Sandgren is quick to note that not only musical numbers were captured in single takes, as the filmmakers often wanted the camera to “participate in scenes, like a character, and many scenes were therefore blocked as single moving takes to engage in the scene more physically.” Opining that single takes were the shoot’s greatest challenge, he adds, “It put lots of pressure on the actors as well as 1st AC Jorge Sanchez, when pulling focus — and on top of that often in a very tight timeframe to capture a specific time of day.”

The cinematographer offers that he learned a lot from working with the music and choreography departments, specifically in using “both the camera and the light more like a musical instrument. It gave us the opportunity to work rhythmically, physically and emotionally with the camera, and react to the characters’ inner feelings with [lighting effects].”

Though the movie's retro feeling certainly served as motivation for capturing on film stock, analog is Sandgren’s general preference for his projects. "Film has so many expressive forms,” he says. “When you choose from Super 8mm, 16mm, 35mm and 65mm, you have more variety of looks than by shooting digital and trying to tweak later in post. We all know how little time we have in post, and adding looks at that point is always scary to me. It's great to capture in camera if you can, and more economical. When we watched the dailies we fell in love with the colors we got and that's the general look we kept.”

Sandgren shot mostly on Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 negative — including all night scenes — and on 250D 5207 for the few midday exteriors. They tested pushing, pulling and normal processing, and ultimately decided on pulling for finer grain. Having rated the 500T stock at E.I. 200 and the 250D stock at E.I. 100, Sandgren overexposed by 1 1/3 stop, and then FotoKem in Burbank pull-processed all footage by one stop.

Both filmmakers had determined that the film would be shot anamorphic. Chazelle, though, was expecting they would frame for 2:39:1, but Sandgren pushed for classic CinemaScope, achieved by shooting 4-perf Super 35mm at 2.66:1 and then cropping slightly for 2.55:1. They used the full height of a Super 35 frame, while Panavision equipped its Panaflex Millennium XL2 cameras with ground glass for CinemaScope composition.

"Damien and I love the wide 1950s format," Sandgren says. "It gives the audience more. We wanted to shoot head-to-toe and get the epic feel. The film was budgeted for 3-perf, but CinemaScope is 4-perf so we accommodated that by rehearsing more and shooting less. Shooting on film and in CinemaScope captured the greens and blues of our lights and the skies in a way digital wouldn't have. Film exaggerates those a lot."

The production did bring out the B camera for straightforward dialogue scenes, such as one in which Sebastian's attempt at a romantic reunion dinner goes south. "That was typical coverage — a two-camera setup to get the acting in sync,” Sandgren notes. “It was very simple: two angles and not even a two-shot profile. Damien just wanted to be on the eye-lines. It felt better to shoot those scenes that way to be able to cut between the cameras and build the story through editing."

Throughout La La Land, bright colors pop from the work of David Wasco and set director Sandy Reynolds-Wasco, from Mary Zophres' costumes, and from the gelled lights. In this scene, an overpowering green glow pushes into Sebastian's dingy apartment, which is a reference to another 1950s movie, though not a musical: Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo (shot by Robert Burks, ASC) — specifically the apartment occupied by Kim Novak's character.

"Linus has this sensibility of magic realism where everything feels slightly heightened but nothing feels too theatrical," Chazelle offers. "You might not know exactly where the colored light or that sense of unreality is coming from. Linus and David were always working on that. I would joke that we wanted to take real settings and locations and make them look fake."

Sandgren says that for this particular scene, "We imagined a neon sign outside Sebastian's window. It would be the worst to have a light like that when you're trying to sleep, but he wouldn't care. He would embrace it and make it romantic."

Hazen was prepared to light the scene more conventionally with big moonlight sources on condors across the street when Sandgren made his surprising request. So instead he lit from outside the window with a mix of daylight-balanced Kino Flo and LED tubes — the latter being brighter and dimmable — both gelled with Fern Green. Hazen found it a bit much.

"When we were lighting the scene a couple of us told Linus, 'This looks horrible. Are you sure?'" Hazen recalls. "And he said, 'It'll look great, trust me.' Then I saw the dailies and I said to him, 'I'm sorry. You were right — that looks amazing.'"

“Our approach was to take what the locations gave us and add a slight amount of surrealism,” Sandgren says. “I like to work with colored lights and often use contrasting colors in lighting. Outside of Mia's theater, for example, in a very emotional single-take scene between Mia and Sebastian, we leave Sebastian alone in front of the theater entrance — which David and Sandy Wasco designed in pink — and we lit with additional pink fluorescent light, as if it was the ‘heart,’ centered in frame, and had [Sebastian] surrounded by the harsh pool of cool white-blue streetlight, lit from a 6K HMI and Plus Green gel under a blue night sky. We wanted to add a surreal and romantic look to this otherwise dull building.”

The filmmakers shot with Panavision C Series Anamorphic Prime lenses. While the 50mm and 75mm saw some action, the 40mm was the go-to. "The 40mm offered a good mix of being able to be wide on location for head-to-toe shots and still being able to go close up,” Sandgren explains. “We felt a 30mm or 35mm would distort too much.” The cinematographer generally shot at T2.8 and used no lens filters save for NDs.

For the shots that required focus-range flexibility, Panavision vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy Dan Sasaki — an ASC associate member — constructed an additional 40mm 2x anamorphic lens with a close-focus distance of 19", so that, as the cinematographer says, "We could go in very close, such as starting in on Ryan's hands at the piano and then pull out wide."

Chazelle and Sandgren embraced the "flaws" of anamorphic, as in a daytime shot in which Sebastian, alone in his sister's bland, beige-brown apartment, plays piano to a record he's spinning. The white curtains are drawn and the 4K Arri M40 HMI sun source outside created a blue flare across the screen. This was no happy accident; it was accomplished with very careful light and lens positioning. "We did our best to make the moment a little romantic because he's doing the thing he loves," Sandgren explains. "It's fun to add that to gritty, dodgy places and try to make them beautiful."

The dance number that opens the film, shot on a closed-off freeway ramp leading to downtown L.A., is a tour de force of staging. It starts with the camera tilting from the sky and traveling alongside cars stuck in a typical L.A. traffic jam. The camera pushes into a driver who, instead of being frustrated, gets out of her car singing along to a tune on the radio called "Another Day of Sun."

It catches on, and other drivers abandon their vehicles to join in, with the camera tracking along to capture the moves of various dancers, acrobats and traceurs, and a band that magical appears in the back of a truck. Per the preferred method, the production first rehearsed the sequence in a parking lot to block camera moves, and then had access to the freeway for one weekend for a full run-through — an idea pushed by 1st AD Peter Kohn — and another weekend for shooting. The filmmakers audaciously thought of capturing the entire sequence in one shot, but that proved impractical.

"We would have shadowed the entire set a few times with our crane, and it would have been terrible work to clean up that type of shadow in the faces of the actors and dancers," Sandgren explains — so they employed the old-school technique of panning where they needed to cut.

The entire musical sequence is composed of three segments seamlessly edited together, the first two shot in the morning and the last one in the afternoon. Aside from some negative fill provided by key grip Anthony Cady to take out the sun, the shots were captured with natural light.

They initially planned to shoot the whole scene on Steadicam, but Robbins wouldn't have been able to smoothly negotiate a 4’-high median in the middle of the road. In the end, one segment was shot with Steadicam — which culminated in the operator stepping onto a crane — while two segments were shot on a MovieBird 45 telescopic crane on an Allan Padelford Biscuit Jr. drivable trailer — functioning as a large dolly — positioned in the far-left lane of four lanes of cars stopped in gridlock traffic. Speakers were spread out along the road, blasting a recording of the song for the performers.

"It was a logistical nightmare, but it was fun," Sandgren recalls with a laugh. "Many times we had these huge challenges and had a hard time believing we could actually do it, but we struggled through." In the case of the freeway scene, they got what they wanted after many attempts. Indeed, 25 takes were required for the Steadicam shot, leaving everyone — especially Robbins — exhausted.

Another challenge was capturing a scene in which Sebastian and Mia, after a movie-date viewing of Rebel Without a Cause (shot by Ernest Haller, ASC), drive up to Griffith Observatory, which is featured in that film. The crew had one day to shoot exteriors and interiors at the location, including a 360-degree Steadicam shot inside by the Tesla coil as the lovebirds begin a waltz.

"We were really restricted in terms of what we could do in there,” Sandgren recalls. “It was a very tricky lighting situation.” The art department ended up adding some practical wall pieces that matched what was already there, attaching dimmable 75-watt household bulbs to them. The crew had two Joker-Bug 400-watt HMIs with 1/2 Plus Green hidden behind two small walls and directed at the ceiling.

They were also able to hide some lights on the ground, including 1K Par cans with 1/2 CTB and an Arri 4K HMI Par, the latter of which was placed behind a wall the art department had built that was put in front of an existing kiosk. The production placed 1,200-watt HMI Pars with 1/2 Plus Green at either end of the corridors and daylight Kino Flos with Full Plus Green wherever they could.

Inside the planetarium, the two become airborne — in fact, pulled by wires — and dance across the cosmos. The location was re-created on stage with a bluescreen illuminated by Kino Flo Image 85s with super blue tubes. The crew otherwise lit from above with 24 Chauvet Colorado RGBA LED Pars behind Light Grid Cloth, onto which they projected images of the stars that would later be added by the visual-effects team. This provided lighting programmer Christopher Ferguson a guide for adjusting the color and brightness of the LEDs to match the shifting light from the various eventual CG celestial objects. Hazen notes, "I also had 20 1K tungsten Pars with 1/2 CTB gel for a cooler feel through the Light Grid to give us more light level overall, also controlled on dimmers."

For the back half of the waltz, professional dancers take over as we see the couple in silhouette. That segment was shot on a 40' bluescreen platform.

For a sequence in which Sebastian and Emma watch projections on a screen, the filmmakers employed an Aaton A-Minima N16 16mm camera and 500T 7219 stock for a grainier look, which lent itself well to home-movie-style shots of domestic bliss. Panavision and Sasaki produced a new T2.8 18mm 2x anamorphic lens that brought a desired haziness to the 16mm footage.

In the mornings, EFilm dailies colorist Matt Wallach, seeking Sandgren's sign-off, would send him stills from the previous day's shoot. The cinematographer would view them on an iPad calibrated with Wallach's projector. They applied a LUT that was arrived at in prep. "The LUT had close to a D6500 white point that best allowed the colors to stand out," says EFilm DI colorist Natasha Leonnet.

Sandgren notes, "Wallach has a sensibility for the nature of analog film stock, and makes very natural adjustments to the image. We both like to embrace what the film negative gives us."

Dailies, generated by EC3 Labs, were distributed via DAX and the cinematographer watched them on his iPad. The filmmakers would sometimes go to EFilm on weekends to watch them DCP-projected.

The director of photography wanted to be as close as possible to the final look by the dailies stage. "I like to have the intention for the look of the film figured out when I shoot,” he explains. “I aim for making decisions in regard to lenses, format, process and lighting so that it's all there in the negative, and I like to make sure I'm right on track — and I want to communicate this look to my director and the visual departments right away. Making precise adjustments on a daily basis makes all visual departments more in sync with what we are aiming for."

The film was scanned by EFilm at 6K with an Arri machine and down-sampled to 4K. Leonnet worked with DPX files using Lustre software, and film-out resolution was 2K.

Leonnet says one of the main orders of business in the DI was to "introduce blue in the blacks to emulate the original Technicolor process." Sandgren likens the finished color to Superman's glossy hair. The cinematographer sat with Leonnet over several evenings after days shooting the sports bio Battle of the Sexes with directors Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris — and, again, Emma Stone. His last look at La La Land was at a remote session at Company 3 in London.

After the team's hard work realizing Chazelle's vision, the film went on to win the best-actress prize for Stone at the Venice Film Festival, followed by the People's Choice Award at the Toronto International Film Festival. Musicals are rare these days, so at Venice, Sandgren and Chazelle were apprehensive about the movie's reception. "The reviews were set to come out at 10 a.m. and we had no idea,” the cinematographer recalls. “The producers felt good but we were scared — 'What are people going to think?' You never know how they're going to react. Maybe you're totally wrong about what you think you've done." But the acclaim that followed, he says, "was so much fun."

Update: Upon winning the Academy Award for Best Cinematography on February 26, Sandgren noted on stage at the Dolby Theatre, "Wow, wow, thank you so much, the Academy. This is such an amazing honor. This film was made with so much love and passion and struggles. And it was all thanks to you, Damien. You’re a poetic genius. And I’m so happy I met you and I really love you, man. Emma, Ryan, I think you’re incredible. Thanks for all the collaboration. Lionsgate, producers and the entire crew. I’m really proud, especially of Ari, Jorge, Tony, Brad, Bogdan, this camera crew, light crew, grip crew, that made this work. And then Cecilia, Betty and Lucy. To my mom, thank you. And to my father, I know you’re watching over us. Thank you so much."