Joan Churchill, ASC — An Evolving Eye

The cinematographer discusses how her work has changed over time, and how “people skills” are an essential tool in non-fiction filmmaking.

The cinematographer discusses how her work has changed over time, and how “people skills” are an essential tool in non-fiction filmmaking.

Independent filmmaker Joan Churchill, ASC has worked as a cinematographer and director on landmark documentaries including Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer and Soldier Girls. Her credits as a cinematographer include Last Days in Vietnam, Citizen Koch, Dixie Chicks: Shut Up & Sing, Punishment Park and Gimme Shelter. In recent works, she has moved past the restrictions of cinéma vérité into a style that engages more fully with her subjects. Currently she is working on several ongoing projects, including My Dinner With Haskell, a documentary portrait of famed cinematographer Haskell Wexler, ASC. She has also been on the Executive Committee of the Documentary Branch of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences for 10 years.

American Cinematographer recently spoke with Churchill after her appearance on a panel entitled “The Female Gaze,” held by the Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York City, where she was joined by Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF; Ashley Connor and Agnès Godard. (See interview with Braier here.

American Cinematographer: Can you talk about the difference between shooting in an observational style, and the more interactive style you’ve been recently using.

Joan Churchill, ASC: That’s the evolution, that’s my evolution anyway. I am left-eyed, so when I had a shoulder-mounted camera, I was invisible. I was just a big glass eye to people. Once the camera came down from my face, it totally revolutionized the way I approached shooting. It made me more a participant.

It’s always been my feeling that my skills are more people skills. The most important thing about the kind of shooting I do is that I show a genuine interest in people. I get to know people; they get to know me.

They’re very curious about me because I am a woman, which is still unfortunately very unusual in this field.

The women on the recent “Female Gaze” panel come out of a bit different discipline than I do. What I do is not based on shots, mid-shots, wide shots, close ups, reverse angles, which is essentially paternalistic. It’s how films have been made from the beginning.

D.A. Pennebaker has a wonderful way of expressing it. He says the most important thing is to be there as a friend in the room. Which I think is a perfect description of what I’m aspiring to be when I’m shooting. I’m a sympathetic person, I want to be accepted by people so that I can follow along in the journey that they’re going on.

“People are very media savvy now. There’s no pretending the crew isn’t there. And it’s more honest to acknowledge that you are there.”

That goes against what many documentary filmmakers assert, that they’re supposed to be objective.

Yesterday I did an interview with somebody who’s making a film about LGBTQ people on television. I worked on [the groundbreaking 1973 PBS doc series] An American Family, so they wanted to interview me about Lance Loud. In preparation for that I started watching some of the shows again, especially the ones he was in. Looking at it now, it’s clear that we were so much a part of their lives. Everybody understood that the minute the camera went up on the shoulder, they were to ignore us, the crew. The crew didn’t exist.

Pat Loud would absolutely not go along with that, she was always breaking that wall, making comments, saying things like, “Oh, there’s the crew.” But we were supposed to be invisible.

One of the kids had wrecked one of their cars, and Pat went out to look and had an argument with her child. When she’s walking back into the house, she says, “Well, I lost that one” to the camera. Which is much more the way I think filmmaking has evolved. People are very media savvy now. There’s no pretending the crew isn’t there. And it’s more honest to acknowledge that you are there.

I worked for 53 weeks on a show called The Residents. We followed interns for their first year in a hospital. It was the most amazing experience to have an entire year, it was as in-depth as An American Family, or even more so.

We knew which people didn’t want to be filmed, so we wouldn’t point a camera at them. Aside from that we had carte blanche to go anywhere. We all shared the same experiences as those residents. We all fell in love with the same patients, almost all of whom died. Pretty soon we were part of their culture. We were feeling the same emotions, undergoing the same things

It meant that we were really able to show what these people were going through, what they felt, the experiences they were having. We used to call it “OTF,” or on the fly, interviews. That’s how we would do our interviews. So if something happened that I felt the audience wouldn’t understand or that I didn’t understand, I would in the moment ask a question about whatever they were doing.

It’s a very casual way of getting at the information instead of formally sitting people down behind a desk and putting a flag and a flower pot behind them and doing an interview in which they become very presentational. It’s just a more genuine way of having an interaction. You are there, you’re in their lives. Why not ask a question in the moment?

“One of the things I’ll find myself doing is just finding a place to be in the room. If I’m in a situation where people are in extreme emotional states, I don’t want to add to their grief by calling attention to myself.”

Objectivity is kind of a false argument. Every decision you make as a cameraperson is a political one, an artistic one. How you frame, where you point the camera is already a choice.

What I try to do is be organic about it, so that I’m not thinking in terms of shots, which is one of the problems I have with the way people shoot documentaries. So often they’re not listening, they’re not being sensitive to the moment, and they’re always thinking, “Well, now I need to get a reverse angle.” They’ll move at a moment that’s really inappropriate. But they’re getting their shots.

I can’t remember if I said this at the “Female Gaze” panel, one of the things I’ll find myself doing is just finding a place to be in the room. If I’m in a situation where people are in extreme emotional states, I don’t want to add to their grief by calling attention to myself. So I’ll find the best place that I think I can get everybody’s actions, and just stay there.

Directors will ask, “Can you now get that reverse angle?” I’ll explain that I’m getting everything I need where I am, and that it’s better to sit and be still.

Are you thinking of the structure of a scene as you shoot? Pennebaker has said that he finds the scene during editing, not when he’s shooting.

That’s true of Penny, I don’t think exactly the same way. I’m always trying to make sure that I do have a beginning and a middle and an end. Once I commit to something, I’ll really cover it. I will change angles, but make it part of a move and make it work. So that when it’s being edited, the editor has a choice of cutting to a new position I’m in or letting it play in real time.

Of course, you need to find your end. I’m always telling my students don’t cut when you think the scene is over. It isn’t. That’s when people start being genuine.

“If you look at all the wonderful vérité filmmakers, they’re all incredibly charming people.”

How close can you get to the people you’re filming before it gets uncomfortable? How do you build trust with them?

So many camerapeople will hang back, they’ll stand farther away from whatever it is they’re shooting. I’m trying to insinuate myself into what I describe as the circle of interaction. It does mean that people have to be willing to have me be part of that circle.

If you look at all the wonderful vérité filmmakers, they’re all incredibly charming people. They’re often really good cooks. Ricky Leacock used to have these gumbo meals, an all-day thing where students would come and everybody’d go shopping together, chopping and drinking wine and then this wonderful meal at the end of it. And Penny too. I mean Penny makes the most amazing paella, I’ve actually filmed it. It’s an all-day process.

They’re interesting, and people are fascinated by them and want to get to know them and are happy to have them be part of their lives. That’s part of why they get the kind of footage they get with people, because they’re accepted.

I’m so much more interested in people than anything else. I don’t even like being a tourist because I’d much rather go and imbed myself in somebody’s life in a foreign city than go see the museums. I’m really interested in what makes people tick, the way they think, why they feel the way they do.

One of the most wonderful things about my life is that the people I have made films about, so many of them have become lifelong friends. It’s a privilege to be invited into people’s lives. I honor that.

“Nobody was saying, ‘Okay you should be the master, you should shoot that side of the stage and the other person should shoot the reverse angle.’ It was all sort of, ‘Let’s shoot what we feel like shooting.’”

Your passion, at times bordering on anger and frustration, is obvious in many of your films.

I come from a political background. My mother was an activist who was named by the Senate McClellan committee as one of the 10 most subversive people in the country. She was considered a Commie and was harassed by HUAC. We had to move to Ojai, a valley directly east of Santa Barbara, when I was 11. We basically got run out of town. So it’s in my blood.

My father made educational films, and his company Churchill Films was audited by the IRS during the Nixon administration five years in a row. In 1973, I moved to England for 10 years. I got audited myself by the IRS. They said I owed all these taxes, something like $37,000, for a grant I got from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to make Soldier Girls. In the end, I won the case because I showed up and did the interview myself with the IRS.

Funny story, turns out the accountant I had hired sight unseen from the UK had been the man, then working for the IRS, who had audited Churchill Films for five years in a row.

It’s a similar political climate today.

The worse things get politically in this country, the more there is to make films about. It’s been a lifeline for documentaries; they’ve become powerful tools.

How do you set up for something like a meeting, where you’re not sure who’s going to speak or what’s going to happen?

I’m working on a film about people who have developed addictions to psychoactive drugs such as benzos, a very common tranquilizer. There’s one scene where a woman is meeting on campus with her friends. She’s very proactive in organizing help for veterans. That scene was shot with me, one camera, literally inside, jumping in and outside of a circle of tables.

There’s another scene where she’s in her class reading a poem she had written. It was shot with two Canon C300 Mark IIs on rolling spreaders. I was shooting the front angle, and the other cameraperson was off to the side having a difficult time focusing on the right person at the right time.

The way it’s cut, it goes back and forth between these two angles, probably because there are two angles. But I find it very disturbing and distracting because I’m being taken out of the power of what she’s saying.

In the first scene, because I was handheld, I was able to follow fluidly the process of what was being said. When they walked out of the room at the end I was able to walk out with them and catch an intimate moment of someone describing what the woman had been like before she got off the benzos. And then we go down in the elevator and follow her off the campus.

If I had been shooting that on the tripod with the Canon C300, I wouldn’t have been able to get out the door and go down to the elevator with them and then down the stairs and walk across campus with her.

There’s also a question of point of view. With one camera, it’s just one point of view. To bring in another camera from a different angle is a different point of view. I find it very disturbing.

You have worked with multiple cameras, for example in Down from the Mountain, a concert film directed by Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus, and based on music from O Brother, Where Art Thou?

For that there were three handheld cameras shooting, and Chris up in the rafters shooting a master.

There was a day of rehearsals and then the next day there was the concert. So, during the rehearsals we were just all over them, in their faces, we were able to be onstage and shoot them rehearsing their music and also lots of green room stuff backstage.

Nobody was saying, “Okay you should be the master, you should shoot that side of the stage and the other person should shoot the reverse angle.” It was all sort of, “Let’s shoot what we feel like shooting.” We were all aware of the other two cameras and what they were doing. Very often I would see that Penny was shooting somebody close to me, so I would move my camera over to the other side of the group and shoot the opposite. It was just very organic. And it completely worked. There was no directing in that sense.

If you let people follow their muse and do what they think is right, how can you then tell a vérité person, “Zoom in now”? Directors have tried to whisper in my ear. I’m not even hearing them.

First of all I’ve got earbuds in, and second of all I’m deeply involved in what is being said. I mean you have to listen, you have to anticipate what the people you’re filming are going to do next. You are so in the zone when you’re shooting that kind of stuff, you can’t even hear somebody else making a suggestion to you.

Fortunately I’ve been hired because people think that I will come back with the goods. There have been so many films that I’ve shot with Barbara Kopple where I never laid eyes on her. I spent a month in Iraq shooting women journalists on my own for Barbara’s film Bearing Witness. And I never saw her once on the Dixie Chicks film, Shut Up & Sing. At one point we had a conference call with the editor who asked, “Why didn’t you take the camera off the tripod for that interview you did?” I said, “I didn’t even bring a tripod.” Barbara was laughing.

“I get very moved when I’m shooting music. I think musicians are too; they’re much more passionate when they’re actually doing their art, singing or playing. Asking them to talk about what they do is kind of like asking me to talk about what I do. It’s really difficult to

put words to it.”

Do you feel you shoot music differently than a discussion or debate?

Yes, I get very moved by music. I used to play guitar myself and fancied myself Joni Mitchell. I grew up in the 1960s here on Sunset Boulevard and worked on the strip at a coffee house called the Fred C. Dobbs where people like Bob Dylan would give me five dollar tips — which would be like wow so much money.

I was very taken by that whole scene. In fact it was very difficult for me to finish film school because I was working from eight at night until four in the morning on the Strip. Luckily, because of my father’s company, I could use his equipment and edit there.

I get very moved when I’m shooting music. I think musicians are too; they’re much more passionate when they’re actually doing their art, singing or playing. Asking them to talk about what they do is kind of like asking me to talk about what I do. It’s really difficult to put words to it. That’s why it’s interesting to watch them when they’re zoned out and making their art.

You play guitar, does that help anticipate what a musician will do?

Of course, absolutely. Bob Neuwirth was at McCabe’s Guitar Shop for one of his shows. I have been shooting him here on the West Coast and Penny and Chris shoot him when he’s in New York. He does these wonderfully weird shows where he gets all his musician friends to come up and play with him. They also play their own music and Bob often has somebody who acts as an interlocutor. Bob doesn’t know what the questions will be, but he has so many stories and it’s always amazing to listen to him talk about his escapades with the likes of Edie Sedgewick or Bob Dylan.

He will never do an interview with anybody. Absolutely refuses. But if you can get him going, he will tell incredible stories about Janis Joplin and the Chelsea Hotel. Endless. Endless.

A couple of weeks ago he was doing one of these shows with all these amazing musicians. Tony Gilkyson, David Mansfield, J. Steven Soles, Bob Thiele, Jr., T Bone Burnett. Before the show,they were just sitting in the green room, and each one of them had new music they were playing for the others. It was just magic to be there, to be sitting in that circle. They understood it too. In fact one of the guys said can I have the footage of me singing that song, it’s the first time I’ve ever sung it in public.

How many projects are you working on at a time?

I tend to work on very long-term projects. I very rarely do a one-day or two-day shoot. I’ve done a couple of exclusively interview shows, the latest one being Last Days in Vietnam by Rory Kennedy. But, generally, I’m not that interested in just shooting interviews.

So the other films are usually grossly underfunded or episodic in nature. You are following somebody’s progress trying to get off drugs and you dip back in every six weeks.

The film that I’m doing about the psych ER, it’s been five years on it. And it’s still not quite done. Right now I’m on call, just waiting here, I’ve got my batteries charged and we’re ready to go. Hoping to find our homeless guy, recently released from jail. We’ve been told he’s living under a bridge.

Another film we’re still shooting after two and a half years, we’ve been following four characters who are trying to get off their psych drugs.

It’s just a long process.

“People don’t really like to hear this, but I think either you have it or you don’t.”

Did growing up around your father’s company help train you?

I’m sure it made me be not intimidated. I was always around film equipment. When I was at UCLA film school, there was nobody I could look to. Maybe Brianne Murphy [ASC], but she was in the commercial world. There were no other camerawomen around.

I’m sure the fact that I grew up working on my father’s crews in the summer helped influence me. It was always part of my existence. It wasn’t so exotic. It gave me the confidence.

My brother and I were in my father’s early films. One was Wonders in the Desert. And Conrad Hall [ASC] shot it and Verna Fields edited it. Connie shot with the [Éclair] Cameflex that both he and Haskell always used, a French camera you could shoot both 16mm and 35mm with it; you just changed the plate.

So you grew up knowing that film was a business, something that you work in?

I think I got that much more from my experience at UCLA. Colin Young, the dean of theater arts, went on to found the National Film School in England, which I think is probably the best film school in the world. The people that Colin brought to teach us were working professionals, amazing vérité filmmakers. Plus, I was part of a visual anthropology course Colin started with Paul Hawkins.

We used to have endless debates. The anthropologists felt that you couldn’t possibly do anything except put a camera on a tripod and turn it on and shoot what happened in front of the camera with a wide-angle lens. And the observational filmmakers saying, “No, no, it’s so effing boring. You have to take the camera off the tripod and follow these people in their lives.” That’s what pushed me into being an observational filmmaker.

You’ve been involved with recording the histories of documentary filmmakers.

I’ve been on the executive committee of the documentary branch of the Academy for over nine years now. We decided to shoot oral visual histories of our branch members. The first person we did was [Russian documentary cinematographer] Marina Goldovskaya. Lynne Littman organized it and I shot it and we got a Russian scholar to do the interview with her. Later, I went to New York for Ricky Leacock’s memorial. Alan Barker, my husband, and I spent two days afterwards with Penny in his office just letting him talk about whatever he wanted to. And, of course, this film about Haskell is about the activist documentary filmmaker, not the Hollywood legend.

Have you wanted to teach?

I don’t teach at an institution, but I do a lot of workshops with Alan. People don’t really like to hear this, but I think either you have it or you don’t. I’m talking about the kind of work that I do, observational, catch as catch can, following people. It’s nothing you can teach. You’re either born with this sense of what to do with a camera, or not.

As Karel Reisz said, “Cinéma vérité is wanting what you get, not getting what you want.”

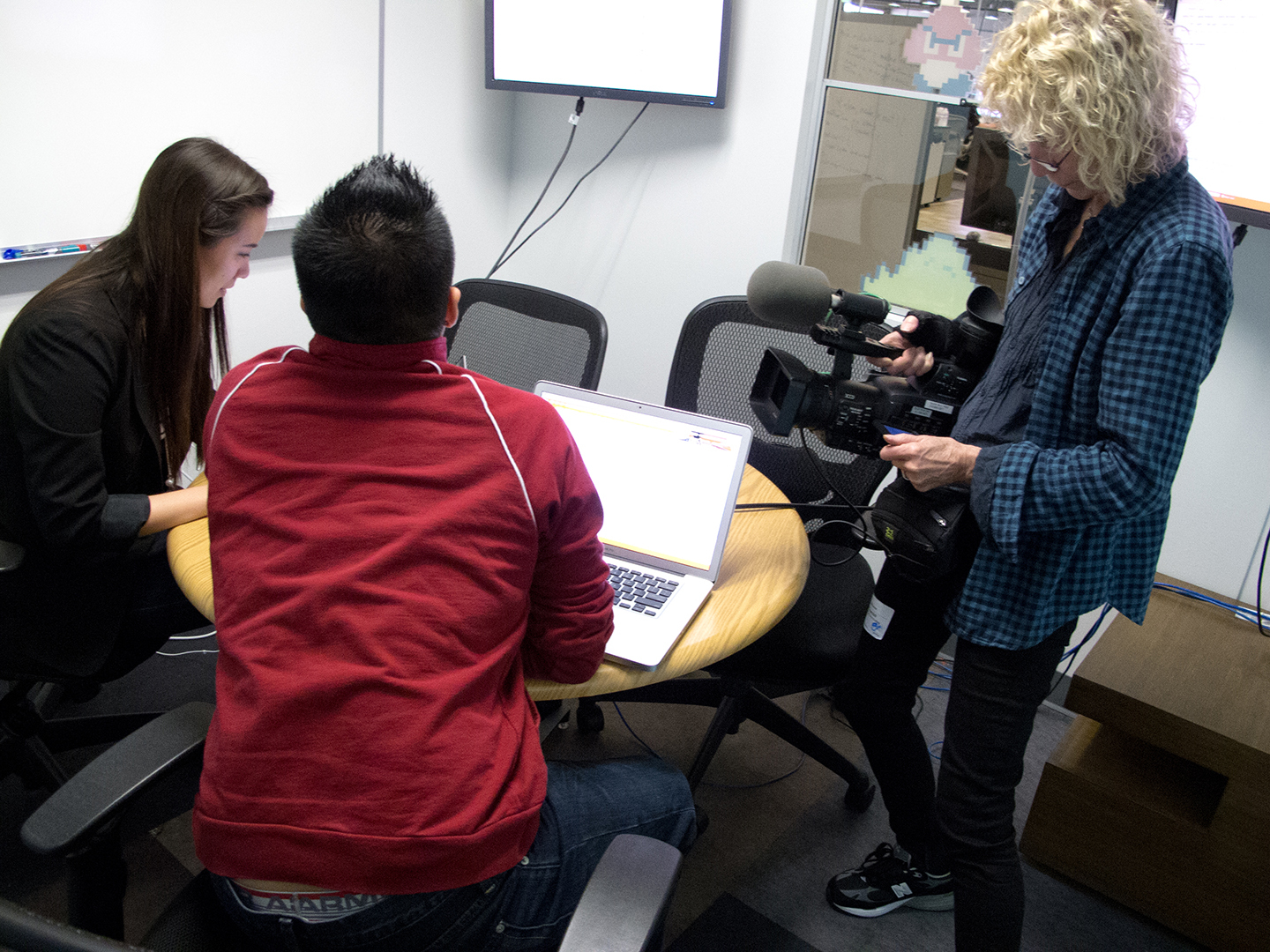

Alan and I do this workshop. Alan comes out of improv, he used to have an improv group. So we set up this scene with a group of cinematography students. And the scene takes place around a large table and it’s a fairly large group of people. We get them to decide what it’s going to be about, it should be something that has some emotional heat to it.

Since they’re students it usually turns out to be about the high cost of tuition or the shitty food or whatever it is in their situation. And then we have a group of students who walk in to confront faculty members or department heads, and we have people going in and shooting this scene.

We have four or five different people taking turns shooting for four or five minutes each. And then at the end I’ll pick up the camera and also shoot so they can see what my choices are. It’s always hilarious. People are coming out who turn out to be just the most amazing actors, nobody had any idea, the quietest little nerd in the group turns out to be the star of the show.

The people who can’t participate because there aren’t enough roles, we get them to do interviews with the participants, who talk about what just happened. Then we look at what has been shot and critique it.

The most difficult thing to learn to do in shooting a documentary is how do you deal with a large group of people sitting around a table. Because where’s the camera going to be? You have to make a decision about who’s the most important person there to follow, or maybe there’s a heated discussion going back and forth. Where are you going to be with the camera? How are you going to best cover this? Do you make moves or do you just stay in one place?

Then you also see the difference when people are talking about something, which is what you’re doing with an interview — you’re talking about the past. You see clearly the difference between being in the present and shooting something as it’s happening, or hearing people talk about it afterwards.

It’s a wonderful experience, it’s always great.