Photographing Apollo 11

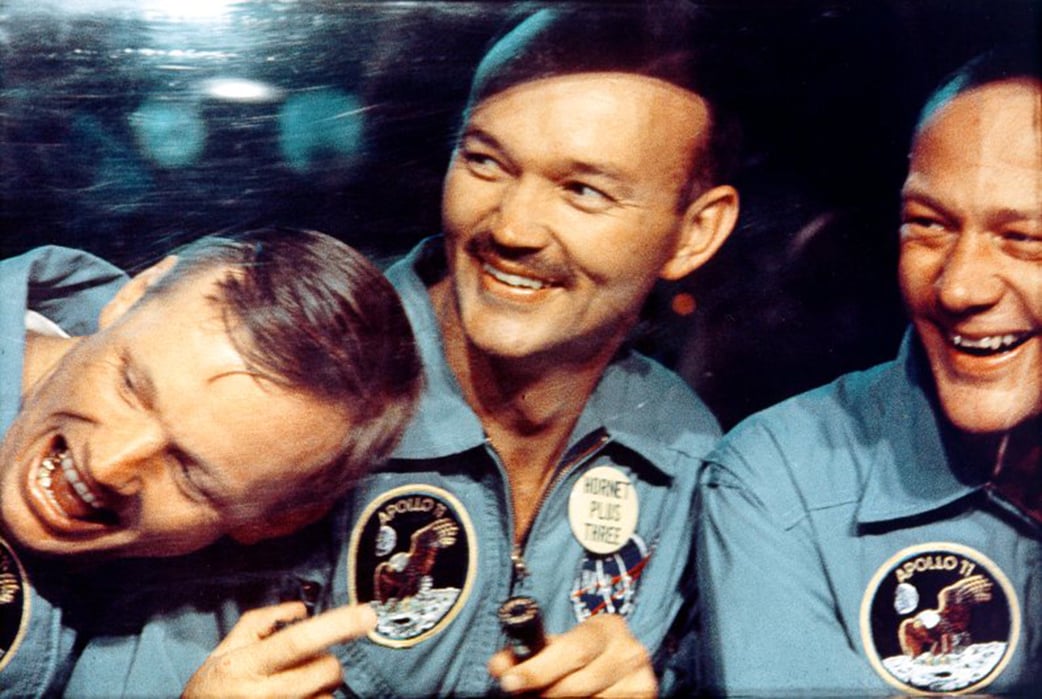

Looking back on the immense efforts taken to photograph the 1969 lunar landing mission — with the astronauts becoming honorary ASC members for their outstanding efforts. (Introduction by James Neihouse, ASC.)

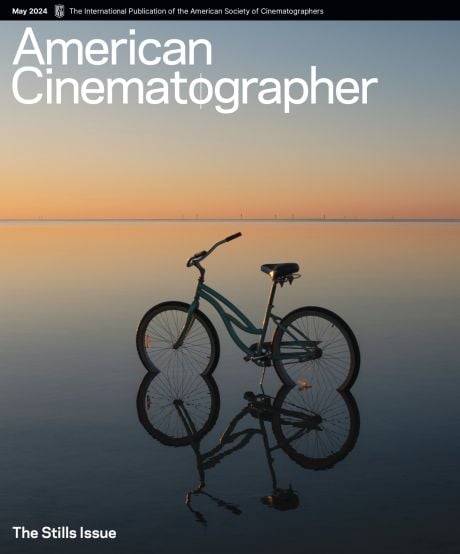

Editor’s Note: To honor the historic Apollo 11 moon landing of July 20, 1969, a special “Filming Man in Space” issue of American Cinematographer detailed the extensive photographic work done to document the complex project in still photos and motion pictures — on Earth, in space and on the lunar surface. What follows is a selection of that end-to-end coverage, as printed in our October 1969 issue.

Some images are additional or alternate. All are courtesy of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, specifically the NASA History Office and the NASA JSC Media Services Center.

Opening this curated collection is a new introduction by James L. Neihouse, ASC — who worked closely with NASA and the astronauts over the course of many years and missions, serving as an Earth-based director of photography on multiple projects, as well as teaching cinematography to those who would travel into space. The results include the documentaries Destiny in Space (1994), Space Station 3D (2002), Blue Planet (2003), Hubble 3D (2010) and A Beautiful Planet (2016).

Most recently, Neihouse coordinated a global photographic team for the project One More Orbit, a record-shattering, high-speed flight around the Earth, commemorating the Apollo 11 landing and a tribute to the past, present, and future of space exploration.

“Space, the final frontier…”

By the time William Shatner spoke those four words at the beginning of the first Star Trek episode in 1966, the American Society of Cinematographers and space exploration had already been linked, taking viewers where “no man has gone before.”

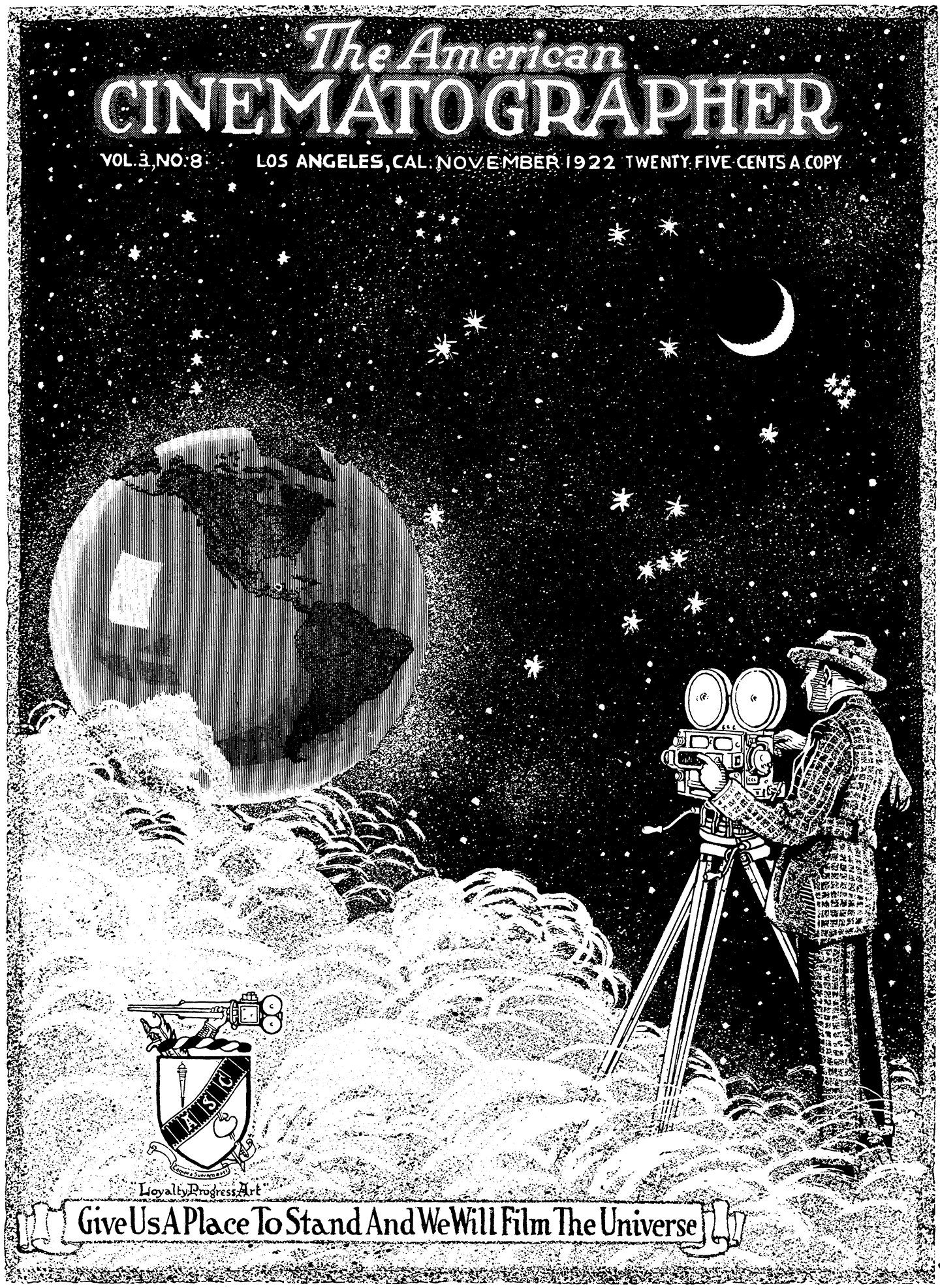

In 1922, decades before the formation of NASA, one of the earliest and most iconic American Cinematographer covers featured an illustration by Lewis W. Physioc, ASC, depicting a cinematographer filming the Earth from an amorphous cloud suspended thousands of miles above the earth with constellations and the moon as the background. The banner at his feet proudly states, “Give Us A Place To Stand And We Will Film The Universe.” Since that time, many ASC members have contributed to hundreds of space-themed motion pictures, both narrative and non-fiction. So it was only fitting that in October of 1969, the magazine would dedicate this issue to the hard work, creativity, and commitment of those responsible for bringing the visual story of the Apollo 11 moon landing to the world.

This special issue contains nine separate articles about practically every aspect of the effort — a lot of it extraordinary — that went into ensuring this historic mission was properly documented for people around the world, and for generations to come.

Having worked on most of the IMAX space films, and being a total space geek, I was more than thrilled when asked to write this introduction for the digital release of the “Filming Man In Space” issue.

Whether by grand design or not, a suggestion made by Apollo 11 command module pilot Col. Michael Collins is the reason I’m writing this. It was by Collins urging that an IMAX camera was flown in space. It was his belief that filming in space in IMAX was the only way to bring his experiences above the Earth back home to share with the general public. That was in 1976 — it only took us until 1984 to actually make that happen with the project The Dream is Alive.

In the early 1980s, I had the good fortune to work with several of these legendary “rocket cameramen” on space shuttle launches, I learned much from these pioneers, so the “Lift-Of at Cape Kennedy” article was especially poignant. I could also personally relate to the “TLC Treatment Given Apollo 11 Photographs” article, as what they went through wasn’t all that different from the procedures we used to insure that our precious IMAX space footage got the tender, loving care it deserved. Of course, our footage didn’t have to go through quarantine like the film coming back from the moon, but that didn’t lessen the pressure felt while watching the developed film emerging from the processor. It’s always good when there’s an image, especially when it is space footage.

While working with the imaging specialists at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, I was able to see, first-hand, some of the amazing images shot in space since Mercury astronaut John Glenn flew an Ansco camera — which he bought at a drug store — aboard the first U.S. manned orbital space flight in 1962. The article “The Camera in Orbit” goes into great detail about the different models of cameras, lenses and film stocks used by the astronauts.

During the Apollo 11 mission, approximately 1,720 frames were exposed, when you contrast that with the more than 319,000 shot by astronaut Col. Terry Virts (the current record), you can really appreciate how far camera technology has come.

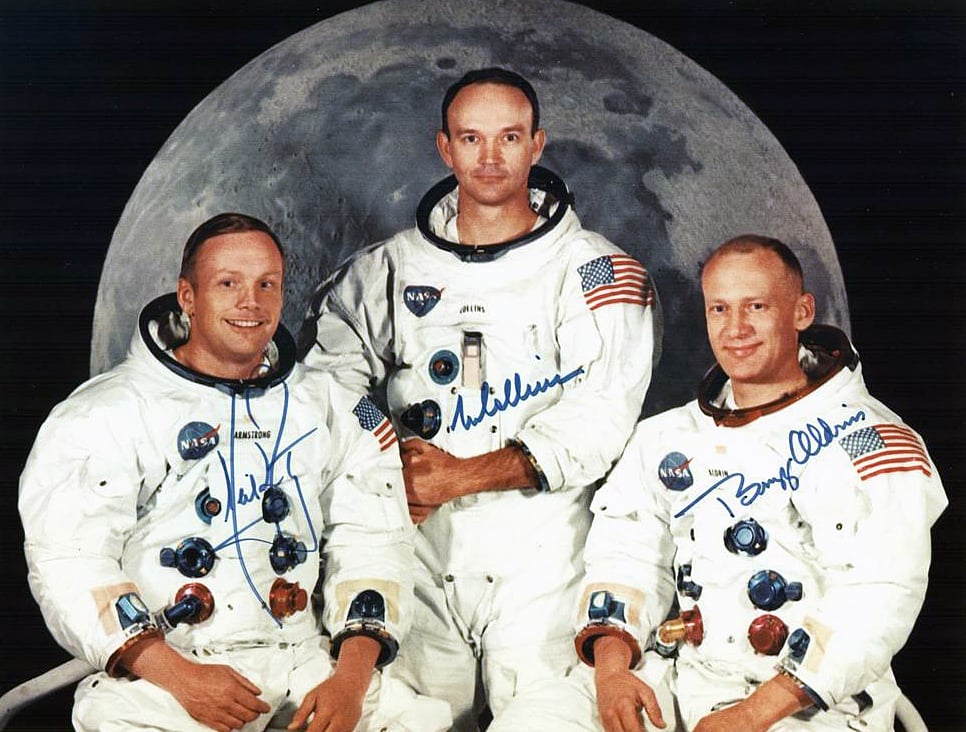

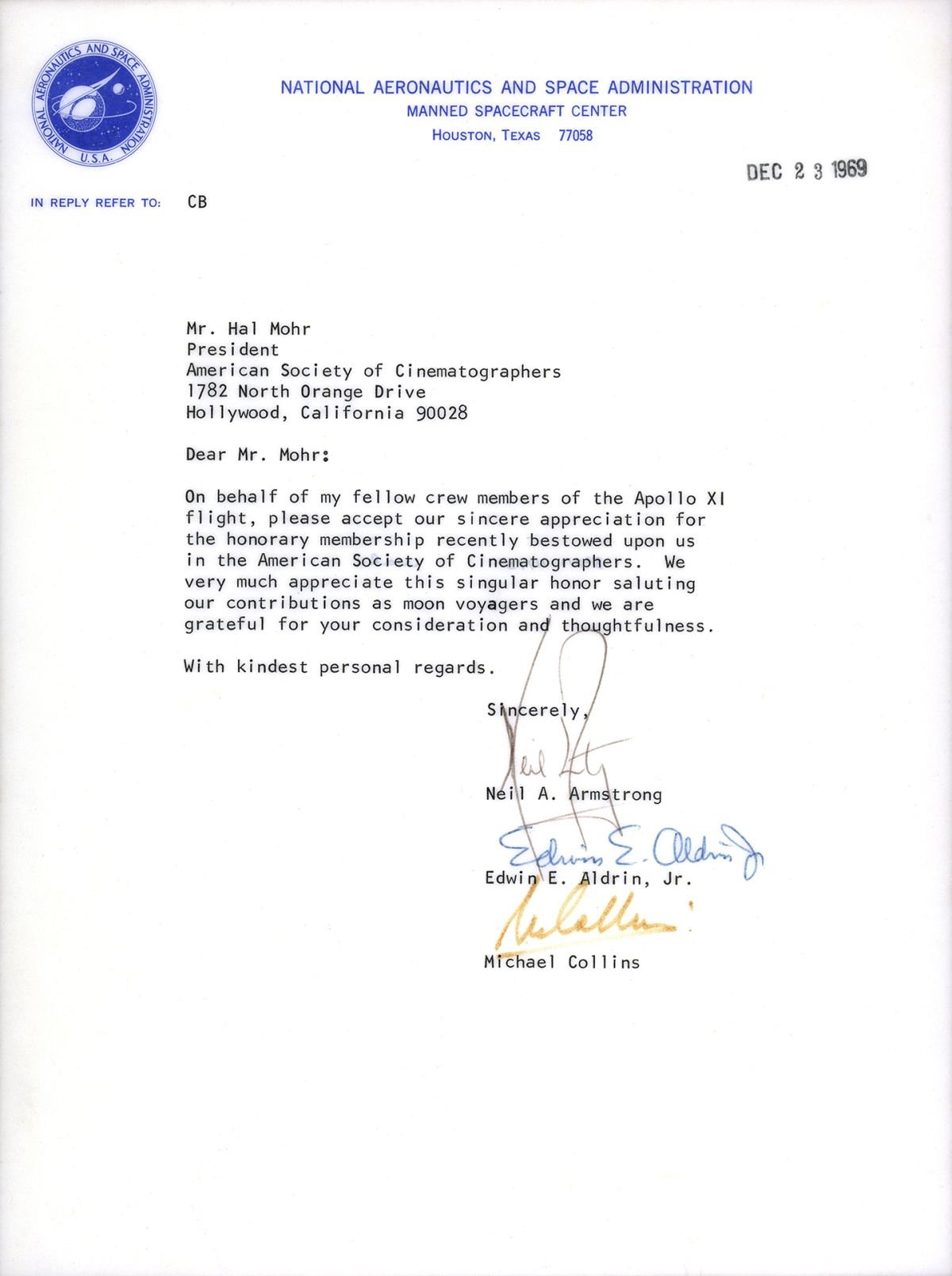

Reproduced below, a letter from the Apollo 11 crew to the ASC is on display at the Clubhouse in the president’s office, accepting honorary Society membership. Four astronauts — Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, Michael Collins and Bruce McCandless — have been on our membership roster for their photographic efforts.

— James L. Neihouse, ASC

“That’s one small step for Man...

One giant leap for Mankind... ”

This special “Filming Man In Space” issue of American Cinematographer is proudly dedicated to the courageous Apollo 11 astronauts, Neil A. Armstrong, Col. Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., and Col. Michael Collins — and to all of the other brave astronauts, past and future, who, for the pride of America and the glory of All Mankind, are blazing a trail to the stars.

“The Eagle Has Landed”

The epic achievement of men in space — and those on the ground — who, working together, scored a perfect landing on another World.

“...We copy you down, Eagle.”

“Houston... Tranquility Base here... The Eagle has landed!”

For countless centuries, man had dreamed of this moment. The moment when men from the planet Earth would first set foot upon the long-mysterious moon. Now, in the sixth decade of the twentieth century A.D., the ancient dream had become a reality.

Even as Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin A. Aldrin, Jr. landed softly in the Sea of Tranquility, preparations for a motion picture to commemorate this historic occasion were well underway. Although many films will depict man’s first landing on the moon, the space agency would officially document the events in its own film.

In establishing the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in 1958, the Congress charged it with conducting research in aeronautics and space exploration, and with “disseminating the results ... as widely as practicable.”

NASA’s Office of Public Affairs conducts a number of varied programs as methods of informing public audiences and of explaining the results of its activities to them. These programs include news releases, publications, exhibits, educational services, television and radio programs and motion pictures.

During the past 10 years, NASA has released well over 100 films for free-loan use by television networks and stations, schools, civic and professional organizations and other public groups, both in America and abroad. Most of these films were produced Ly commercial or educational film producers, under contract and supervision from NASA. Some-usually all-stock-footage productions-were produced by NASA staff personnel.

NASA cameras have provided millions of feet of documentation and engineering footage, a valuable “spin-off” benefit of the wide-ranging research and development activities of the agency and its contractors. If tests or training functions go wrong, such film can provide a valuable aid to the reason for failure and what must be done to correct it.

NASA depositories near Washington and at several of the agency’s major research centers contain more than 12,000,000' of 16mm color footage, limited amounts of 35mm and 65mm footage, thousands of color transparencies and black-and-white photographs, and miles of sound track audio tape and video tape.

Only a small percentage of this material can be used in films, TV and radio series, and school materials which are “packaged” for release by NASA. The agency has a liberal policy, however, of cooperation with other producers who wish to utilize these and other NASA resource materials in their own informational, educational and industrial films.

With agency approval, producers can purchase suitable stock footage from contractor-operated laboratories, for space-related films ranging from Super 8 home movies to 70mm feature producers. NASA believes that such a policy helps other filmmakers in a broader interpretation of the space age.

In addition to a limited number of films intended primarily for public audiences, the agency also produces film reports for training and management purposes. Many of these more technical films are also made available for secondary and college audiences and the scientific community. The current NASA Film List for general audiences includes about 100 titles.

The space agency attempts to be innovative in its public release films, seeking techniques of presentation which will make the viewer feel he is an eye witness participant in the events. Although the technical details of Apollo missions are often similar and repetitive, NASA seeks a distinct style for each new film.

Before the Apollo 11 mission took men to a lunar landing, NASA’s audio-visual staff had dealt with the series of Mercury and Gemini missions in film productions. But as the Apollo flights took man closer and closer to the Moon, public requests for NASA films on each mission increased.

The Apollo 8 Christmas-time mission to the Moon was presented on film with interpretative comments by leading Americans from many fields. The Apollo 9 flight to test the lunar module in earth orbit was shown as a pictoral space-ballet and was cut to the orchestral score from the Beatles’ film The Yellow Submarine.

Apollo 10 took men within 60 miles of the lunar surface, and was presented in a NASA film as a chronological, suspenseful drama.

Apollo 11 was unique. For the first time, men would land on the Moon. Regardless of what took place in the years ahead, this space flight would stand as man’s first encounter with another world.

By the time the crew returned home, nearly a billion people in most of the world would have witnessed the exciting events through television and communication satellites. There would be network documentaries, educational films, home movies and other film interpretations following. But requests for a NASA film were already coming in.

Since the picture would be produced entirely from stock footage and color stills, and since there was great pressure to have prints in distribution as soon as possible, NASA staff decided to make this film themselves.

Before Apollo 10 lifted off the launch pad, planning meetings on the Apollo 11 film were being held. Background footage on training, hardware assembly, testing, the “rollout” of the Saturn V-Apollo to the launch site-all were reviewed and selection for masters was made. But most of the final picture must await the return of the astronauts with their priceless first-time pictures.

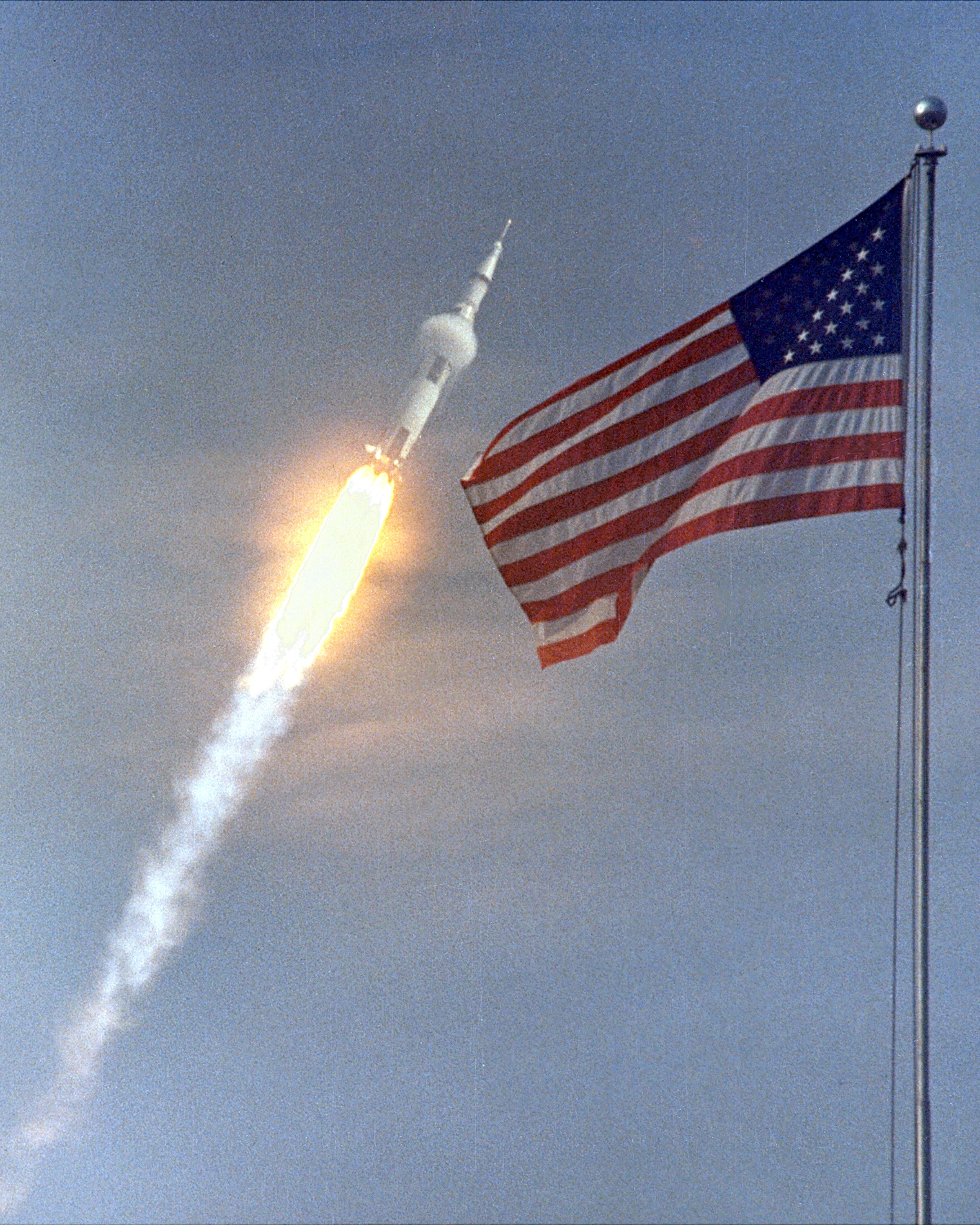

July 16: The Apollo 11 lifted off the pad at the Kennedy Space Center. The event was recorded from many angles, including engineering cameras merely feet from the rocket, housed in special shock-proof coverings. En route to the moon, a television camera was used by the crew to send back color pictures of some of their activities.

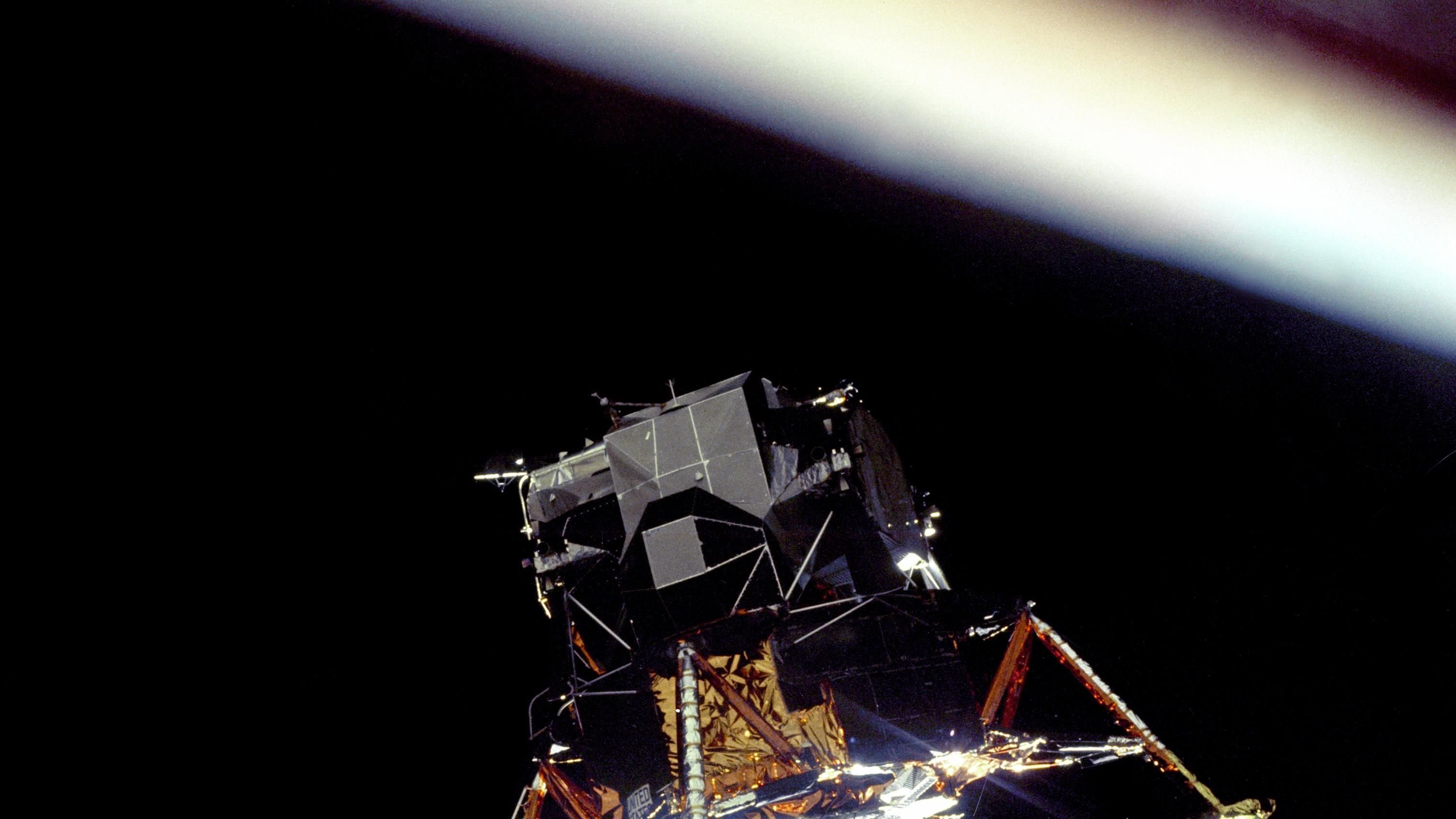

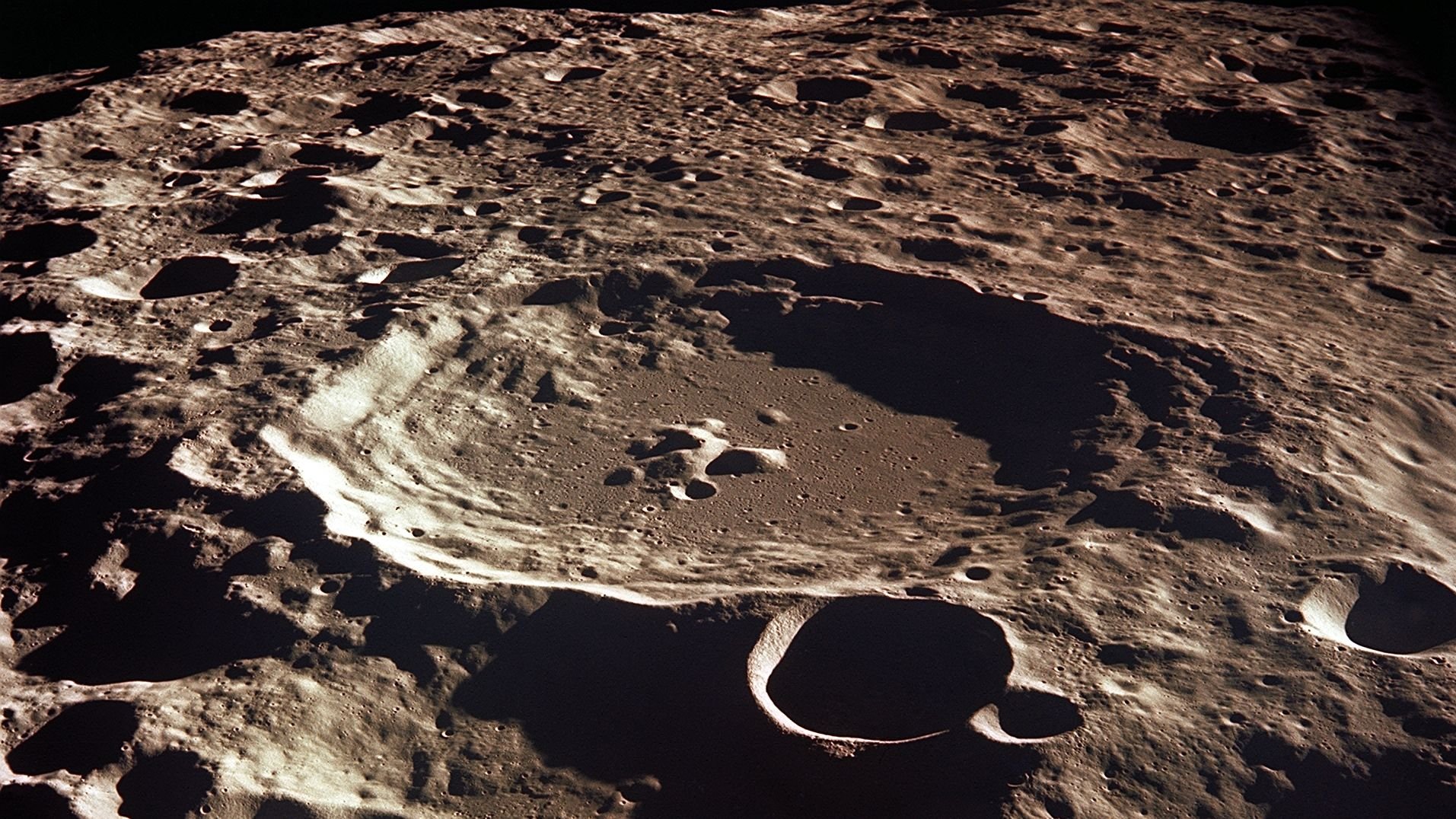

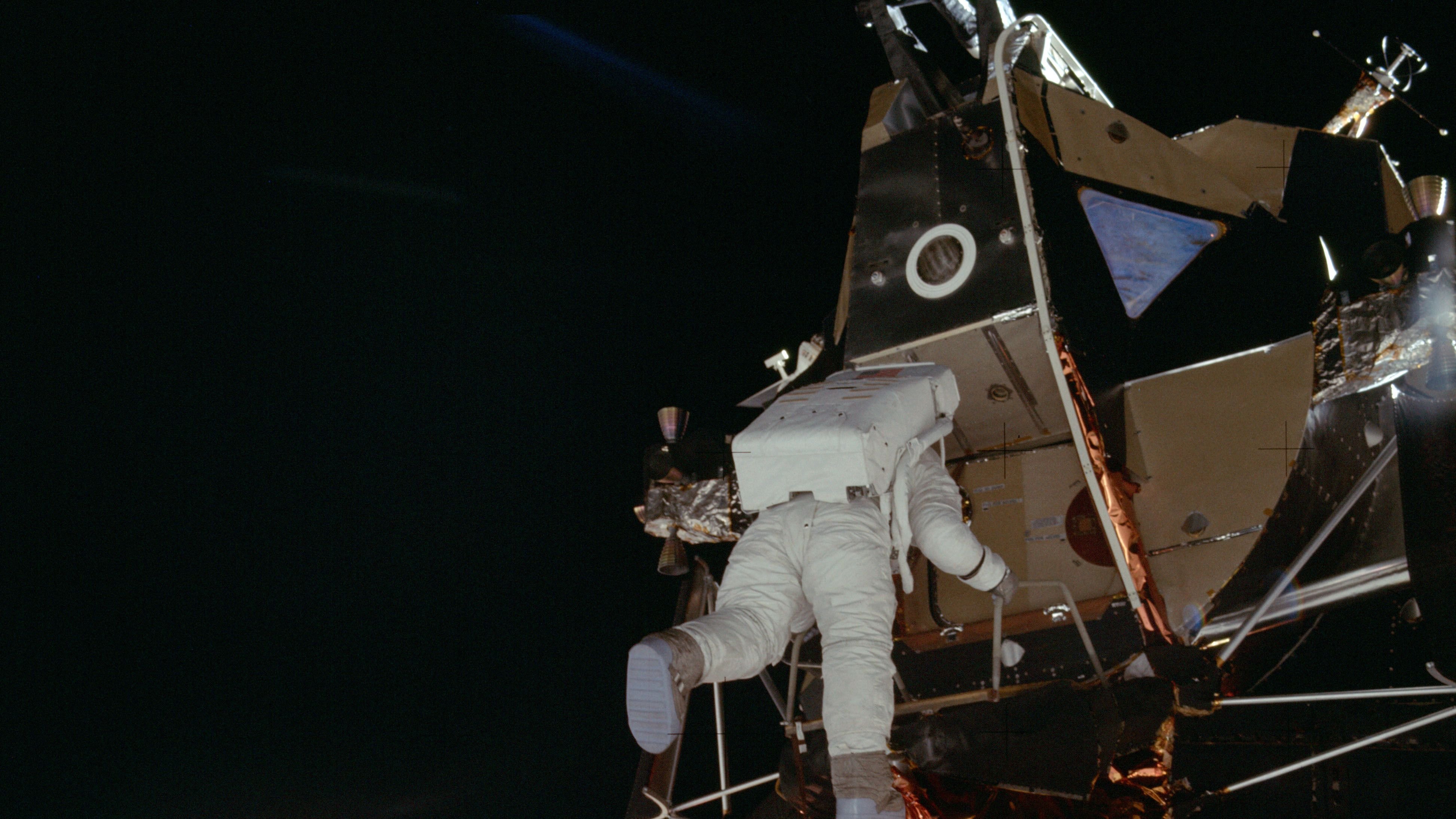

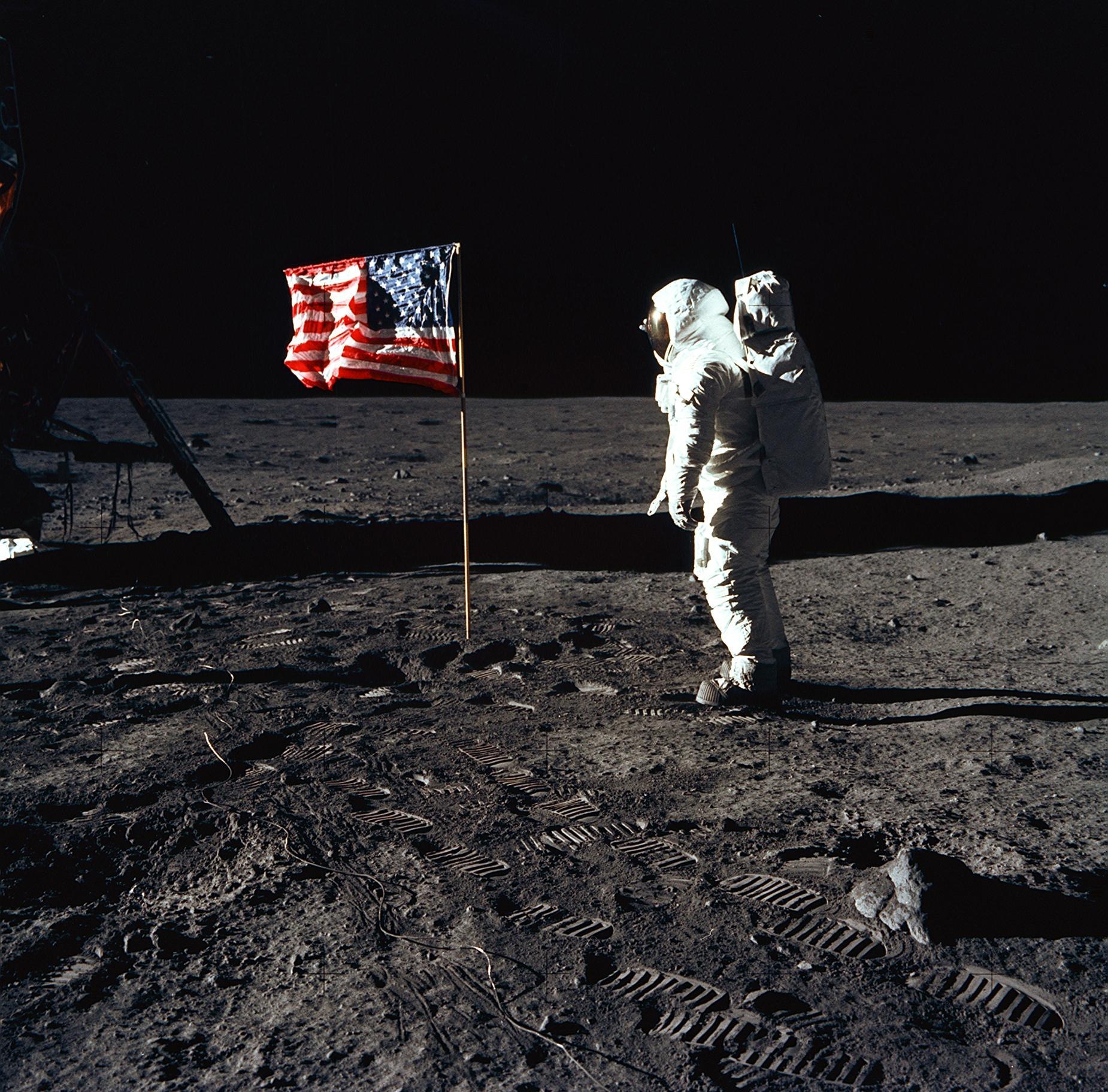

July 20: Apollo 11 reached the moon and lunar module “Eagle” separated from the command module “Columbia” and descended to the surface. On-board film cameras covered most of this activity with remarkable clarity, including the breath-taking moment of touchdown. On the lunar surface, the astronauts would be busy with programmed activities: the collection of rock and soil samples, placement of scientific apparatus and commemorative artifacts, tests of locomotion, and so forth. They also took motion pictures and still photographs. After two and a half hours, the moon voyagers had to re-enter their spacecraft, rest and prepare for the rendezvous. En route home, there would be more photography.

July 24: Shortly after dawn over the Pacific Ocean, the fiery ball of the Apollo spacecraft was seen streaking back into the earth’s atmosphere-recorded for the first time by a camera.

The men were home. Anxious hours and days would follow. While Astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins remained in isolation for examinations and briefings, and technicians and scientists began a careful examination of the moon-matter they had brought back, the NASA film staff began to shape up their film production.

After a brief delay, the on-board 16mm footage and the 70mm still photographs were carefully processed in laboratories at the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center. Soon, masters of this material were on their way to Washington for the NASA film; portions were being released as available to the news media; and composite stock rolls of mission highlights were being prepared for use by other producers.

Around the clock, the visual material now poured into the NASA Headquarters Depository. Launch footage from Kennedy; on-board footage and stills from Houston; recovery footage from the Pacific landing site; video tape-to-film transfers from labs in California and Virginia.

For the members of the NASA Headquarters motion-pictures staff, editorial and technical personnel of the contractor laboratory in Washington, and a consultant producer-designer, the next several days were almost one unending day. The new material was excellent and most of it could be used.

The film would concentrate on activities on the lunar surface, but most of them had been shot with an engineering camera at one-frame per second and could not be used immediately. Still photographs were chosen and filmed on an animation stand. Pre-landing footage had to be pared down, intercut with scenes of man on the Moon. Footage on some of the Lunar Receiving Lab experiments did not arrive, so alternate decisions were made. There was not enough commentary by the astronauts themselves, so work was held up until the end of the isolation and the televised press conference.

Finally, on August 15, the film was completed. Within a few hours, the printing machines were humming and release prints were being shipped to TV stations, NASA libraries, and awaiting audiences.

The Eagle Has Landed: The Flight of Apollo 11 will be widely seen. It was designed as a visual experience through which each viewer might share some of the feelings of the men who made this epic journey to the Moon and the varied earth-bound people who helped them prepare for it. The 28-minute production has been televised by several hundred commercial and educational TV stations, seen already by many organizations throughout the country.

A narrative sound track has been prepared for later prints which will be available to school children and teachers. Prints of the film are being sold for noncommercial use by the new National Audiovisual Center, National Archives and Records Services, Washington, D. C. The U.S. Information Agency has distributed the film abroad with narration in more than a score of languages. A government committee has selected the film for entry in several overseas film festivals.

The Eagle Has Landed was produced by Clayton Edwards, NASA, designed and directed by Ted Lowry. Associate producer was Lynn Moore, NASA. Bastian Wimmer was the editor, and editorial services were provided by Byron Motion Pictures, Inc. of Washington. The narrator for the revised version is John Flynn, and the script is by Walt Whitaker, NASA. Original music in the film was composed and conducted for earlier NASA films by Bernardo Segal.

The mission is over, and NASA scientists are working on future manned and unmanned space missions. The Apollo 11 film is completed, and the NASA film personnel are busy with other films. Hopefully, the next film can be done at a more leisurely pace.

The completed film, presented by the U.S. The National Archives and Records Administration:

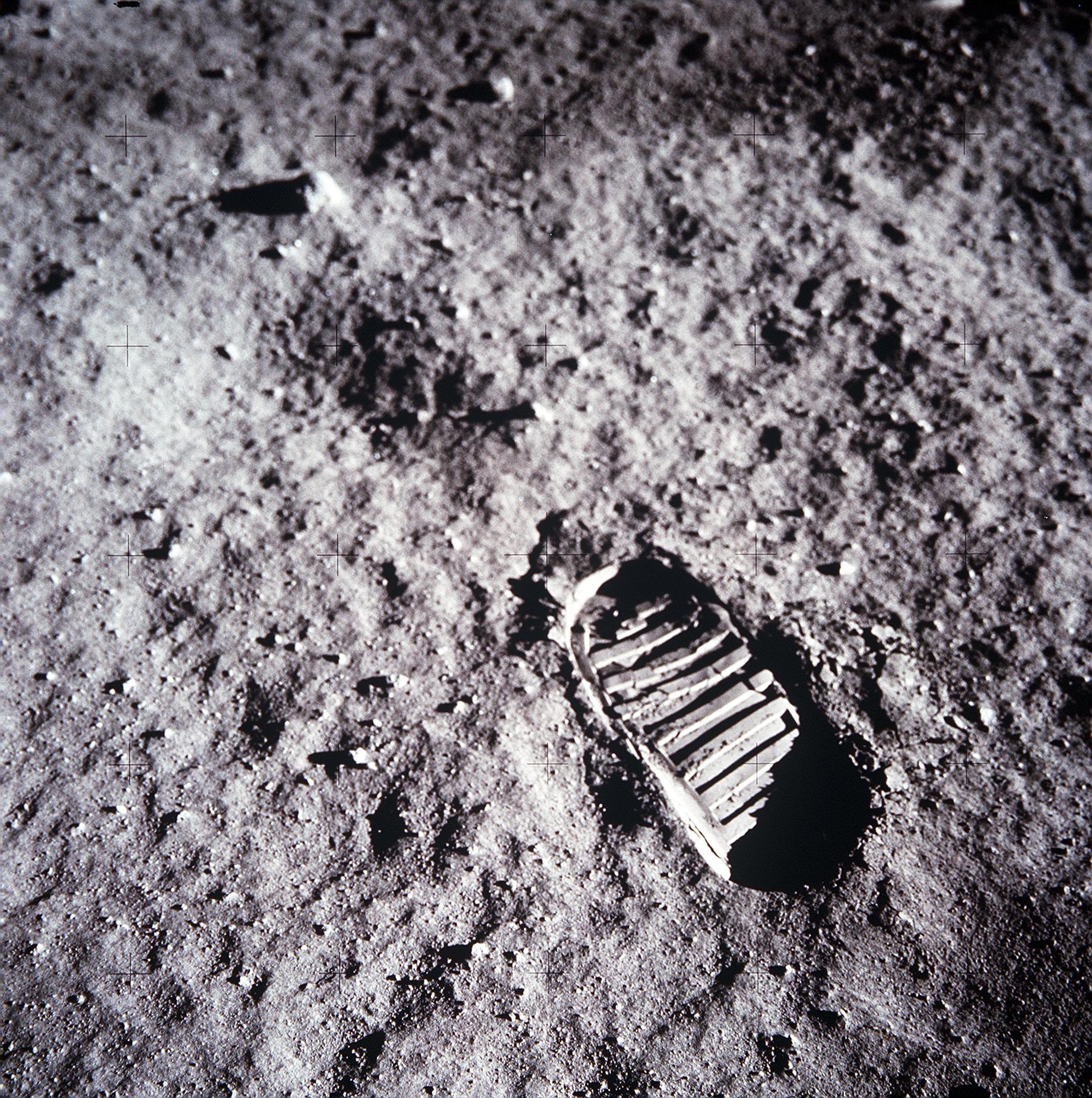

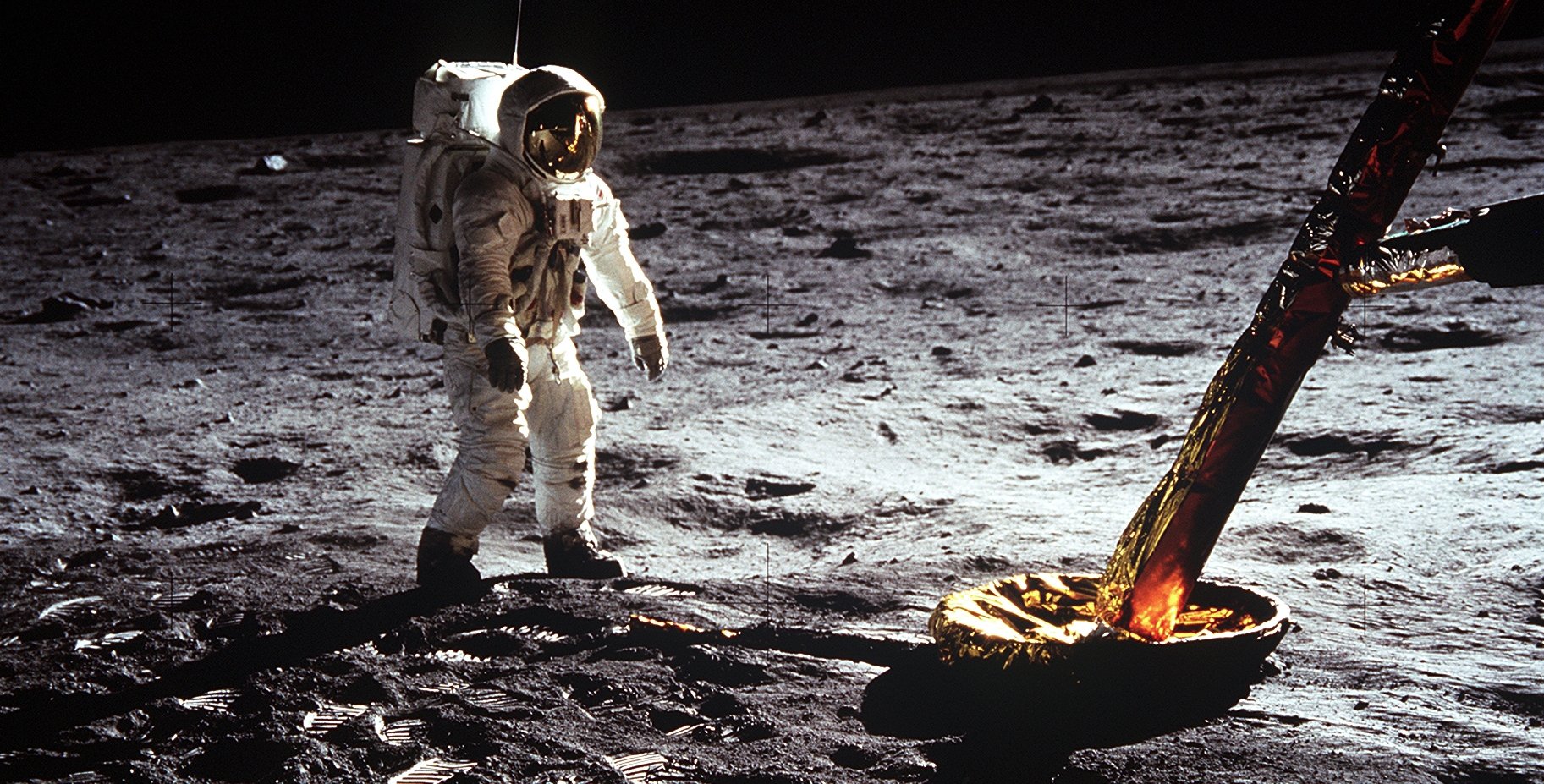

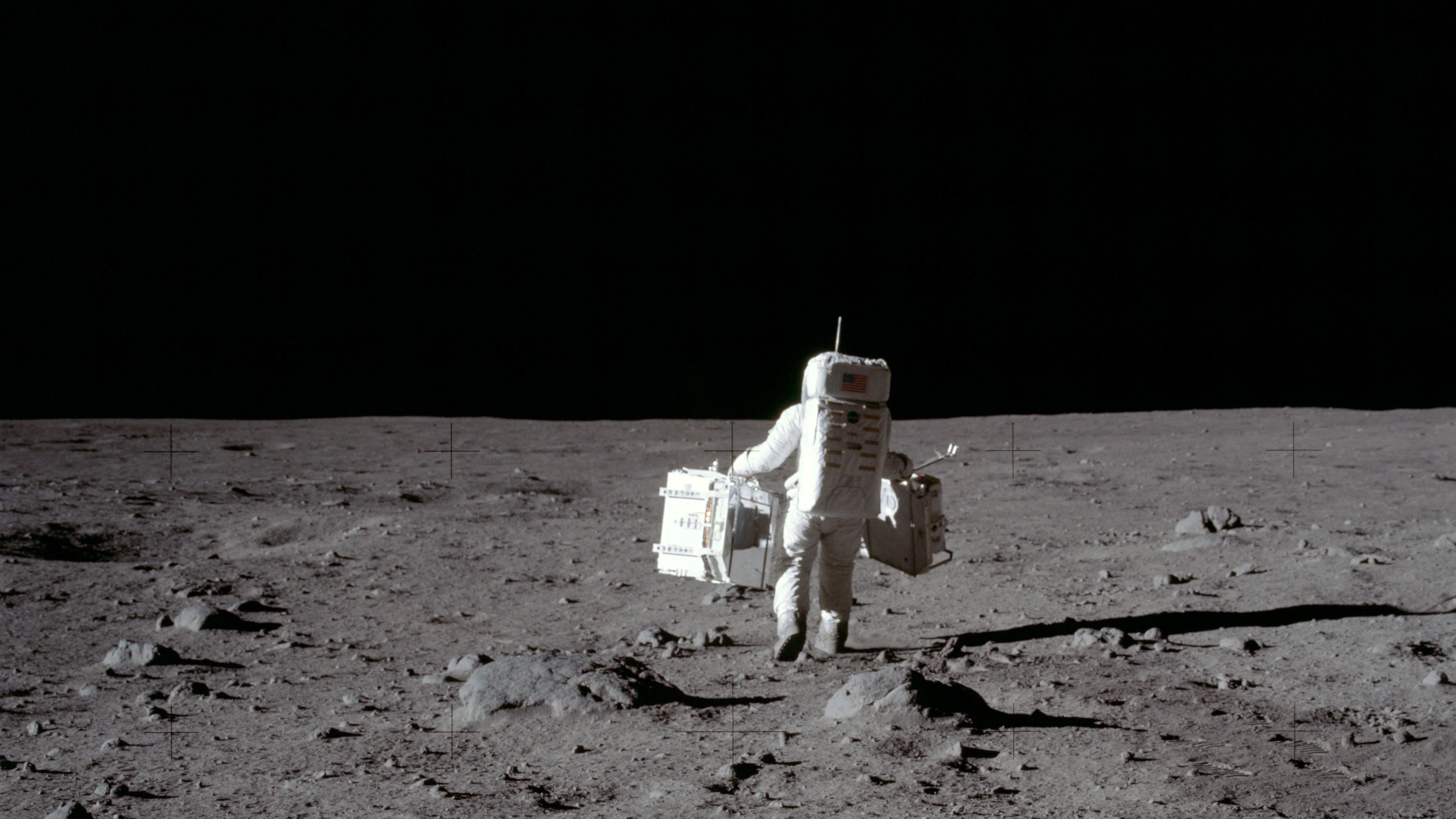

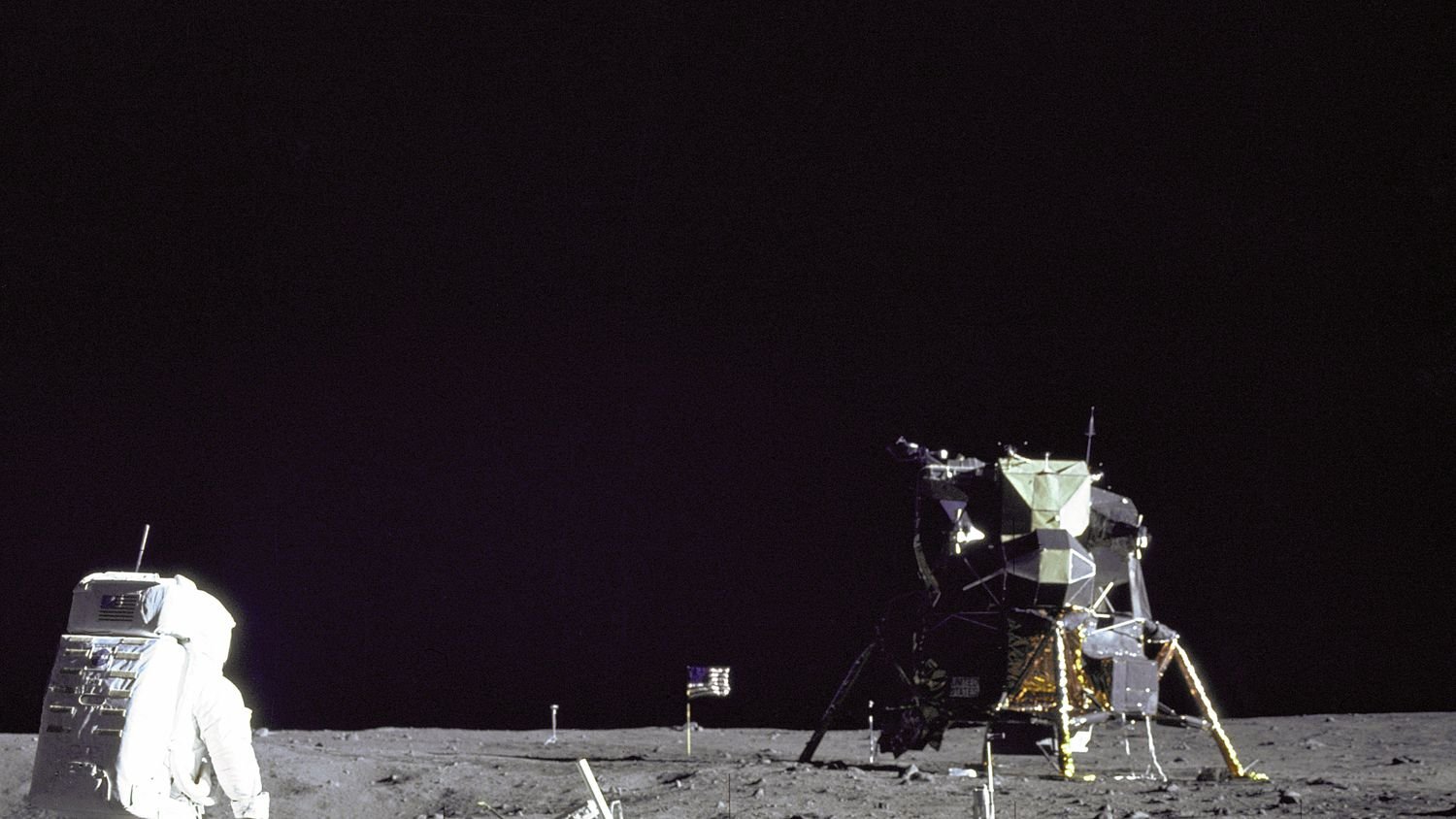

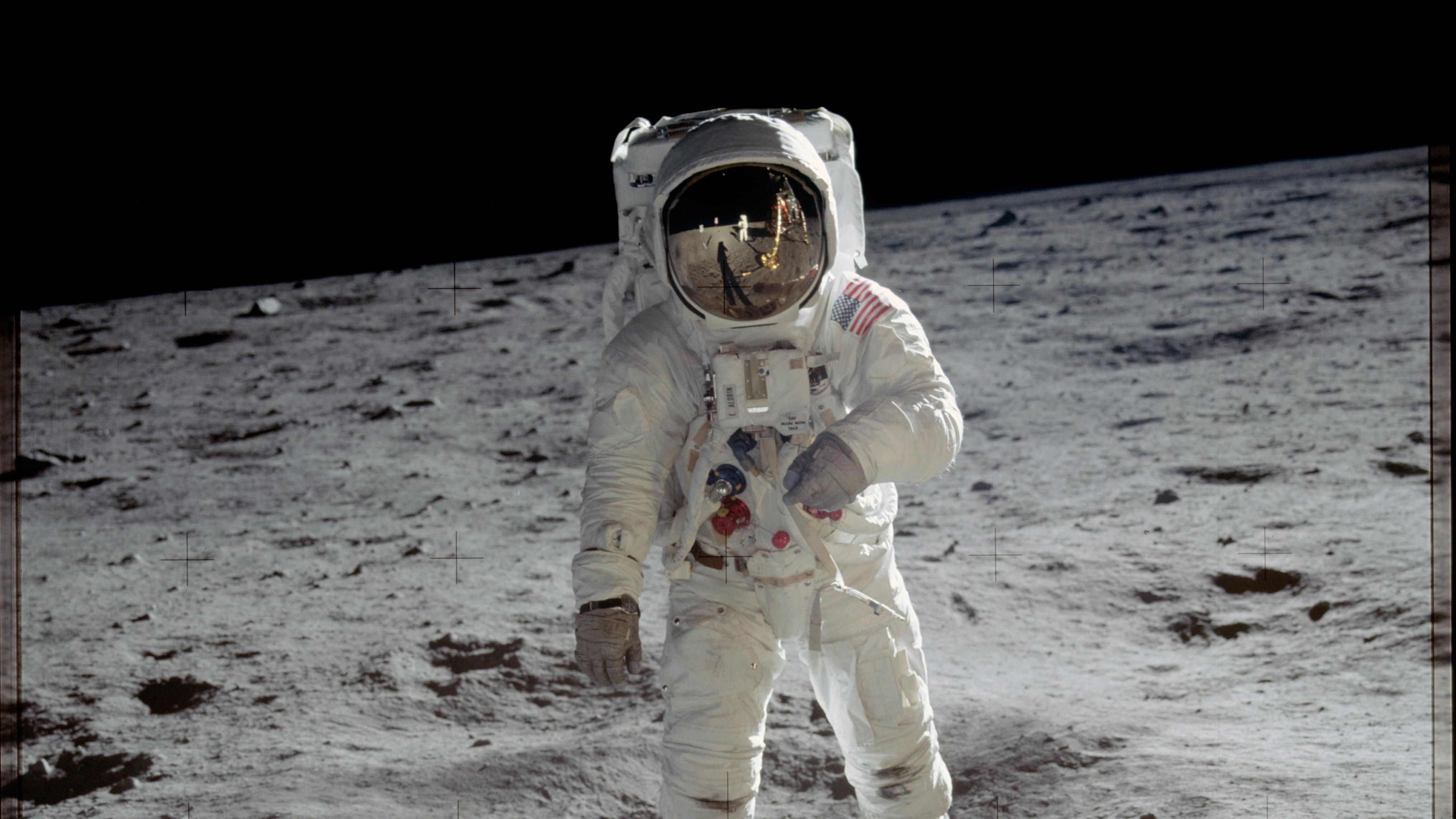

Color photographs of the Apollo 11 lunar flight and moon-walk were exposed in deep space by Astronauts Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin Aldrin. Needing no captions, they are presented simply as a “gallery” of photographic Space Art.

Documenting Man’s Walk on the Moon

The Photographic Technology Laboratory at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center faced a unique challenge — that of documenting on film for posterity sights in the Universe never before seen by the eye of Man.

By John Holland, Jr.

Head, Technical Laboratory Branch

and Andrew M. Sea Ill

Chief, Audiovisual Branch

Photographic Technology Laboratory

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

On July 20, 1969, 1,700' of the most dramatic motion-picture film in the history of man was exposed on the surface of the moon. Its drama, of course, lay in the fact of where it was exposed, rather than its artistic achievement. Even so, this film footage, shot by two amateur cinematographers, is destined to become the most famous in history.

Actually, the 1,700’ of 16mm color film exposed on the lunar surface in the form of motion pictures was just part of the photographic mission to be handled by Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin.

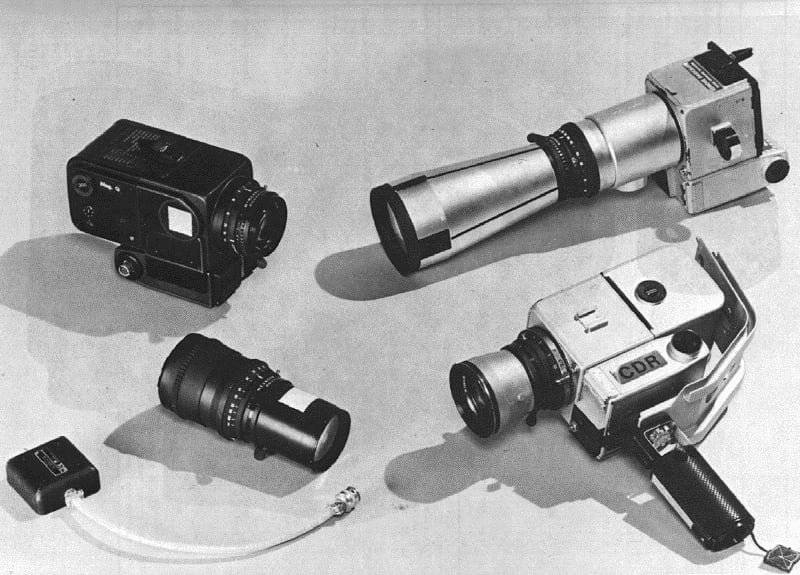

The Apollo 11 crew was equipped with three camera systems. The motion-picture system — a specially built, electronically controlled, variable-frame-rate 16mm camera — was designed to operate both as a bracket-mounted automatic unit during the lunar landing approach, and as a handheld unit during the lunar excursion phase of the operation. This camera system, used on all the Apollo flights to the lunar area, can be operated at rates of 1-to-24 frames per second to accomplish specific tasks.

The motion-picture camera was backed up by a still camera system modified to accept 70mm motion-picture film in 35' rolls. A third camera system was added to the Apollo 11 complement to make detailed photos of the lunar surface. This unit, a 35mm stereo close-up camera developed by the Eastman Kodak Company, was used to produce 17 photos showing the three-dimensional details of selected lunar features.

Films selected for use on the historic Apollo 11 mission were Kodak Ektachrome EF film SO-168 (ASA 160), in 16mm and 70mm; Kodak Ektachrome MS film SO-368 (ASA 64) in 16mm, 35mm and 70mm; and 70mm Kodak Panatomic-X recording film SO-164. All films used were fabricated on Kodak’s Estar thin base, which has a 2½-mil film thickness, as compared to the standard 5-to-7 mil thickness. This reduced thickness allows up to 33 percent more film to be carried on weight and bulk — critical to space missions.

Several considerations determined the selection of the relatively low-speed color films employed on the lunar landing mission. Previous Apollo flights in the lunar area, for example, had recorded specific radiation levels. Our studies of the radiation effect on film — conducted here at the Manned Spacecraft Center and other locations, including Kodak’s Rochester facility — had indicated that high film speeds accentuated the fogging effect created by exposure to radiation. This, in conjunction with the relatively high-light level on the daylight surface of the moon, indicated that the Kodak Ektachrome MS color film, with an ASA index of 64, would be the best choice for the lunar filming. Coincidentally, and indicative of the uncertainties of space travel, the Astronauts of Apollo 11 encountered significantly less radiation on the lunar surface than previous Apollo fly-bys of the area had recorded.

Kodak Ektachrome E F SO-168 was selected for use within the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) to cope with the lower-light levels encountered there.

All films used on the Apollo 11 flight were coated on the Estar thin base at Eastman Kodak in Rochester, New York. Prior to flight time, a NASA aircraft flew to Rochester to pick up the special film batch and fly it to Cape Kennedy, where it was stored under refrigeration.

Similar caution and special preparation were taken at MSC-Houston, where the lunar films were to be processed in the Technical Laboratory Branch facility. Several weeks prior to the lunar flight, all processing equipment in the lab was completely stripped and refurbished. A number of pre-flight simulations were run to check both equipment and chemistry. Then, to be absolutely sure that no mistake would endanger the one-of-a-kind film to be brought back from the moon, Kodak experts in each of our processing fields were called in to re-check our own preparations.

When the historic film was delivered to our laboratory, all was in readiness. The 16-35-70mm Ektachrome SO-368 color film exposed on the moon — a total of 785' — was placed in the High Speed Equipment Company processor using the Kodak ME-2A 75 chemistry. This unit, extensively modified by NASA, essentially is two machines employing a single set of chemical tanks. It is capable of processing 16mm, 35mm and 70mm film footage simultaneously or separately at a rate of 35' per minute.

The 16mm Ektachrome SO-168 motion-picture film returned from the moon was processed by a similar piece of equipment using the Kodak M E-4 elevated temperature chemistry, at a rate of 90'-100' per minute.

Within minutes, a deep sigh of relief echoed through the laboratory. The processed camera stock emerging from the processors was good.

The processed film was printed quickly for release to news media. Then, we settled down to producing corrected color prints.

Using an Acme Optical Printer equipped with an additive color head and punched tape control, we expose Eastman Ektachrome Release Print Film, Type 7388, for all 16mm release prints. The flexibility and color quality of this material gives us the needed leeway to compensate in printing for variables introduced in exposure.

While Astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin, for example, have been trained in photography, neither can be classed as a professional cinematographer. Under the stress of what must have been the most exciting event of their lives, they made small mistakes in exposure. Similarly, the technology of the camera systems creates printing problems. The 16mm motion-picture camera’s variable frame rate must be compensated for in printing. And, when employed within the spacecraft, this camera system is bracket-mounted to shoot through a mirror, resulting in a flopped image on the camera stock.

After months of preparation, precaution, and even fingercrossing, the big day came and went without special incident. Our equipment and personnel did their jobs without a hitch. The historic lunar landing films were processed and printed and released.

Yet, important as the film footage from the moon was, it constituted only a very small part of the motion-picture work being done at the Photographic Technology Laboratory.

The Photographic Technology Laboratory at MSCHouston is headed by John Brinkmann, who has overall responsibility for both film production and processing. The Audio-visual Branch of the Laboratory is responsible for film production, as well as maintenance of the NASA motion-picture film library, film distribution and broadcast services.

Audio-visual’s 47 people — seven civil service personnel in the management group, with 40 staff contractors supplied through the A-V Corporation, Houston — produced 31,000' of silent film and over 7,000' of synchronous-sound film, all in 16mm color, in the month of July, for example. Four sound-color films, totalling 82 minutes of stock, reached the answer print stage of production, while two other films were completed through interlock. These films were in addition to the footage produced in connection with the flight of Apollo 11.

In addition, Audio-visual received, and catalogued 73,736' of 16mm color film from suppliers and contractors connected with the Apollo program, incorporating it into the Stock Film Library. Under NASA contracts, suppliers must document all stages of design and fabrication of space mission components on 16mm Kodak Ektachrome Commercial film exposed and processed to space agency specifications. This material is retained in the Stock Film Library for use in preparation of technical support film reports, training films, film clips for public relations uses, congressional reports and mission films. In all, Audio-visual produces 800 to 900 minutes of documentary films each year, ranging from 7-to-10-minute Astronaut profiles for release to news media, to 15-minute quarterly reports for the Office of Manned Space Flight in Washington, to 30-to-40-minute progress reports on all work in progress at the Manned Spacecraft Center.

The Technical Laboratory Branch at MSC has 13 civil service management personnel and operates with a 60-man contract staff to handle all photographic quality control, and still and motion-picture processing. An average of about 1,000,000' of camera and print stock per month is run through the Branch’s processors, with the bulk in print stock to meet the distribution needs of the Audio-visual Branch. About 95 percent of the motion-picture film processed is 16mm color stock, with the remaining five percent consisting of 70mm (about four percent) and 35mm (very little).

While the Technical Laboratory Branch was directly concerned with handling of the lunar landing films, the Audio-visual Branch now takes over. Segments of the motion-picture film exposed on the moon will be incorporated with stock footage from various phases of mission preparation and with new footage to be produced at MSC to create a variety of reports.

Astronauts Neil Armstrong and “Buzz” Aldrin were part of the NASA photographic team during their walk on the moon. They were the location camera crew. The American space effort and the moon itself were the “stars.”

You’ll find a PDF of NASA’s complete 1970 Apollo 11 lunar photography report, detailing their equipment and methods, here.

TCL Treatment Given to Apollo 11 Photographs

How the world’s most famous photographs were accorded precision processing after an elaborate de-contamination procedure.

“I’m waiting for the world’s most famous courier,” quipped Richard Underwood, Chief of the Precision Photographic Laboratory at the Manned Space Center in Houston, as he described the procedure the precious photographs from Apollo 11 would follow in getting from the moon to the anxiously awaiting world press.

Underwood was, of course, referring to the Apollo 11 craft’s crew bringing nine Hasselblad camera film magazines back to the Center’s lab for processing. Possible contamination from the moon extended the film-handling procedure considerably, as he then detailed.

Attention shifted abruptly to the photographic laboratory as soon as safe recovery of the returning moon visitors was apparent. The lab is responsible for special handling of film and interpretation of still photographs as well as processing.

The still photographs Armstrong and Aldrin took documenting their historic epic journey assume an equal significance, justifying the eagerness with which they were awaited. Requests for the first release of black-and-white and color photographs were unestimable, according to Ann Bownds of the Still Photo Press Library at the space center who described them as “stacked to the ceiling.”

The magazines, exposed with three Hasselblad E L/70 cameras by the Astronauts and protected in plastic, were taken from the spacecraft and immediately put into another set of sealed plastic bags. The plastic bags were then given a sterilizing bath for 15 minutes in a solution of 5,000 parts per million of sodium hypochlorite. The film load was then split and flown in two separate aircraft like their precious co-load, the moon surface samples.

After their arrival at the Lunar Receiving Lab, the bags were opened and the magazines reviewed for processing priority. The magazines chosen for the first batch went into the darkroom and the film removed from the magazines on their spools.

Up to this point; the procedure, except for the sealed plastic bags in which they traveled, has been the same as it has been for the approximately 7,500 Hasselblad still photographs brought back by astronauts from Mercury through Apollo flights. But the next step in the darkroom was especially for this flight’s film: it was a re-spooling of the film with an interleaving of a polyester material.

The interleaving allowed the decontaminating gases to circulate throughout the roll of film. An 18% ethylene oxide (dichlorodifloromethene) mixture was used in an Autoclave at 78°F together with 28 inches of mercury. Thirty inches of mercury is a perfect vacuum for 16 hours.

Following this was a test of the decontamination: bacilli were introduced into the spools and incubated for 24 hours in a nutrient. Their survival would indicate a failure of the decontamination process. The strain of bacillus chosen for the test is strong enough to survive lunar environment.

After this last step, which tested favorably in the dry run time and again, practically assuring positive results, normal processing could begin.

But which rolls should be processed? With nine magazines of over 1,400 frames to choose from with only eight at the most to be released at first, careful consideration was given this question. The subjects of each magazine was reviewed and the selection finally made by administrative and public affairs officials.

The Hasselblad photographs taken on the moon in the film magazine coded S were especially valuable. Not only were they the first of this incredible feat, but the camera was outfitted with a special Zeiss Biogon 60mm lens and a Reseau plate for precise measuring of areas photographed. The grid marks show up as crosses along the edges of the 2¼-inch square photographs.

Since magazine S contained what were, at that moment, probably the 127 most important photographs in the world, NASA wisely refused to let these precious frames go through in the first batch of the decontamination process, despite the fact that the world press was eagerly awaiting them. If something had gone wrong, they didn’t want that particular roll of film damaged.

Ironically, it was in the handling of that precious magazine S film that the photographic industry achieved the dubious distinction of having the first man to touch lunar soil — with his bare hands, that is. As he reached into the sealed plastic bag for the exposed Hasselblad film magazine, Terry Slezak, photo lab technician, got more than he expected, including instant fame.

At the moment he was contaminated, Terry was performing the first step on the long road to eventual printing, that of identifying the coded magazines and reviewing their contents. In this way, NASA officials were able to give a priority to the magazines for processing.

Inside the sealed plastic bag was a note from Neil Armstrong explaining that this was a very important magazine, the one exposed on the lunar surface, and that it had been dropped by him. After retrieving it, Armstrong put it into its protective plastic, moondust and all.

Whether history will consider Slezak to be a hero (or simply not too bright) for having handled a “moon magazine” without wearing suitable protective gloves, remains to be seen.

The special camera which exposed the famous magazine S, designated the Hasselblad Data Camera by NASA, differed from the two used on the Command Module and the LM which were the standard versions of the electric Hasselblads that have flown since Apollo 8. The camera that remained aboard the Command Module for use by Astronaut Collins was equipped with two interchangeable Zeiss lenses, the Planar 80mm and Sonnar 250mm. Collins employed this camera to shoot the exciting return link-up with the LM plus some outstanding earth shots, and switched to a 250mm lens for some excellent lunar surface photographs.

Armstrong and Aldrin had a standard Apollo Hasselblad anodized in black to use inside the LM, and the special “silver” one for the EVA. Their prime instruction once down safely, was to photograph everything they could from the LM just in case they had to take-off without performing the EVA. All other activities on the lunar surface were photographed producing the spectaculars printed in every major national and international publication, including this special “Filming Man in Space” issue of American Cinematographer.

As a precaution, together with magazine S, there were included in the second batch to be processed one additional color and three black and white rolls. The first batch included magazine R, which Aldrin exposed from the LM, plus one more color and three black and white rolls.

After more deliberation of the processed rolls, the chosen frames were then printed and distributed which, on Apollo 11, kept the processing lab working at full capacity for 24 hours a day.

The first groups of photographs were delivered to the press in record time. They were from the magazine exposed inside the LM. An additional four photographs were released the next day from that same group of four magazines initially processed.

Underwood and his group accomplished their monumental task with such expediency the surprised press found themselves with a new batch of photographs about every 24 hours. A press conference called to calm the clamor from the press for pictures, indicated a much slower pace.

The accelerated release of photographs was due to the tremendous push by the lab team to work as long and efficiently as is humanly possible, in all systems working smoothly, and in farming out part of the printing. (Private printing facilities in the area were saturated and still the demand exceeded the supply.)

As if the huge task were not enough in itself, a slowdown in procedure had to be made up by the crew. The time was accounted for in the two planes bringing the film at different times and in the procedure after arrival.

When they arrived at the Lunar Receiving Laboratory, rock boxes and other things in that particular area had to be removed before the bags could be opened to begin the work on the films. By the time they were allowed to begin handling the film, the crew had been on duty 20 hours and judged too tired to handle what must be some of the most valuable film in the world.

Besides the intricate decontamination procedures, the lab established its own sensitometric characteristic curves of the films the astronauts used and built their own chemistry for the processing. Other considerations are how the astronauts used the film and the spacecraft’s radiation, pressure, temperature and humidity, all of which could change processing techniques.

All of the lab’s problems were accentuated by an accident which fortunately occurred pre-processing instead of during. Taking painstaking precaution with the precious film, the lab had tested decontamination procedures for two years to develop a reliable system. It worked perfectly until three days before the film was to arrive. Then a roll of film was ruined by a partial liquefying of the gaseous sterilizing solution. A small umbrella was constructed inside the Autoclave to prevent it happening again.

The exacting and sometimes exasperating work by Underwood’s group will reap rewards for some time to come. Not only do they deserve a special salutation from the world’s press, but from the scientists who will be kept busy studying the photographs for some time. The stills made with the Hasselblad cameras will be blown up hundreds of times as will tiny portions of them so that minute details can be studied.

The expectation of excellence in Hasselblad still photographs is so great that when a condition of micro-mottling occurred during a processing test of black-and-white film, the lab’s experts re-built the entire chemistry for processing. The scientists would not accept the photographs in any condition but perfectly sharp. The combination of Hasselblad and laboratory precision has given scientists of different disciplines reliable, important study material since 1962.

Lift-Off at Cape Kennedy

A record number of Technicolor camera crews trained their lenses on what history would call “Man’s boldest thrust into the future.”

The role of Technicolor, Inc. in “Filming Man In Space” goes back to 1964, during the early days of the Gemini flights. Having, since then, become an integral part of the U.S. space program, the company’s role was given increased importance on January 1, 1969, when Technicolor became the prime contractor for all photo support, not only for NASA, but for the Air Force, Army and Navy operations within the Cape Kennedy region.

In July, Technicolor assumed new contractual responsibilities with NASA and the Air Force to function as sole producer and processor of motion picture and still photos at Cape Kennedy Air Force Station and Kennedy Space Center, Florida.

When the historic flight of Apollo 11 to the moon lifted off from Kennedy Space Center on July 16, Technicolor, Inc. employed a record number of more than 200 still and motion picture cameras and a staff of 263 people — including 48 cameramen — to provide photographic coverage of the event for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Under the direction of Robert Forster, project manager for Technicolor’s Florida operations, the intensive photo support for Apollo 11 included 16mm, 35mm and 65mm color motion-picture coverage, as well as 35mm, 2¼ x 2¼, 4 x 5 and 70mm still picture documentation.

Functioning in its capacity as sole producer and processor of motion picture and still pictures at Kennedy Space Center, as well as at the Air Force Eastern Test Range, Technicolor provided rush processing at nearby modern laboratories-still photos being finished by its lab in the headquarters building at Kennedy Space Center, while motion pictures were processed by the Technicolor-operated facility at Patrick Air Force Base.

For coverage of the launch of Apollo 11, Technicolor crews positioned about 150 cameras on and about Pad 39, the site from which the 363-foot Saturn rocket lifted off with its three-man crew en route to the moon. Most cameras on the launch tower and adjacent to the pad were started by an automatic sequencer within the Launch Control Center, located about three miles from the actual launch site.

At lift-off, Technicolor operators also manned the telescopic tracking cameras, situated at remote locations on Cape Kennedy and ranging along the Florida coast north from New Smyrna

Beach to Vero Beach on the south. These cameras not only filmed the Apollo in its early stages of flight, but also fed live TV “pool coverage” to all three major networks, the latter by means of a 500-inch focal-length lens tracking facility at Patrick Air Force Base.

Following the completion of each mission, a documentary film is prepared for NASA records. At the same time, 65mm footage is processed for use by commercial motion picture and documentary producers who may desire such widescreen material. Still photos, invaluable in engineering and historical documentation, also are provided for the communications media.

During the Apollo 10 mission, Technicolor crews utilized nearly 45,000' of original motion-picture film, and in a four-hour period, turned out well over 5,000 still prints.

Some surveillance cameras operated as slowly as two frames per second while other high-speed cameras exposed 500 or more frames per second, stretching time so that the eye could pick up every detail of an important action. Cameras could be placed in areas hazardous to humans yet, properly protected and remotely started, were able to record information unobtainable in any other way.

In addition to immediate launch support activities, the Technicolor personnel in Florida operate one of the finest optical shop facilities in the Southeastern United States, plus a full-scale motion-picture production unit that turns out safety, documentary and training films for both NASA and the Air Force.

The company’s role in documenting the historic lunar flight was not limited to filming of the launch. NASA also awarded Technicolor a contract to convert into motion-picture film all color and black-and-white television transmissions made by Apollo 11 to earth from the moon.

Master television tapes of the historic moon flight and landing were flown from Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, to Technicolor’s Vidtronics Laboratories, Hollywood, where the actual conversions were made. NASA officials there supervised editing of a half-hour film to be distributed worldwide while the flight was still in progress.

Television transmission from the moon’s surface was in black and white. Technicolor’s experts used an electronic beam recorder for the film conversions, providing the highest fidelity available in the world today, according to Joseph Bluth, vice president of the Vidtronics Division.

The conversion to motion picture film allows much wider use of the historic pictures from outer space than would be possible by videotape. Technicolor made the first conversion to color film of color tapes transmitted from outer space during the Apollo 10 flight as an experimental project for NASA.

To follow through on documentation of the Apollo 11 project, NASA assigned three Technicolor crews to provide full Panavision film coverage of astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins from their initial “coming out” press conference in Houston to the Presidential banquet at Los Angeles’ Century Plaza Hotel.

The Technicolor crews were “leap frogged” between Houston, New York and Chicago for the filming-with two crews covering the finale in Los Angeles the night of August 13.

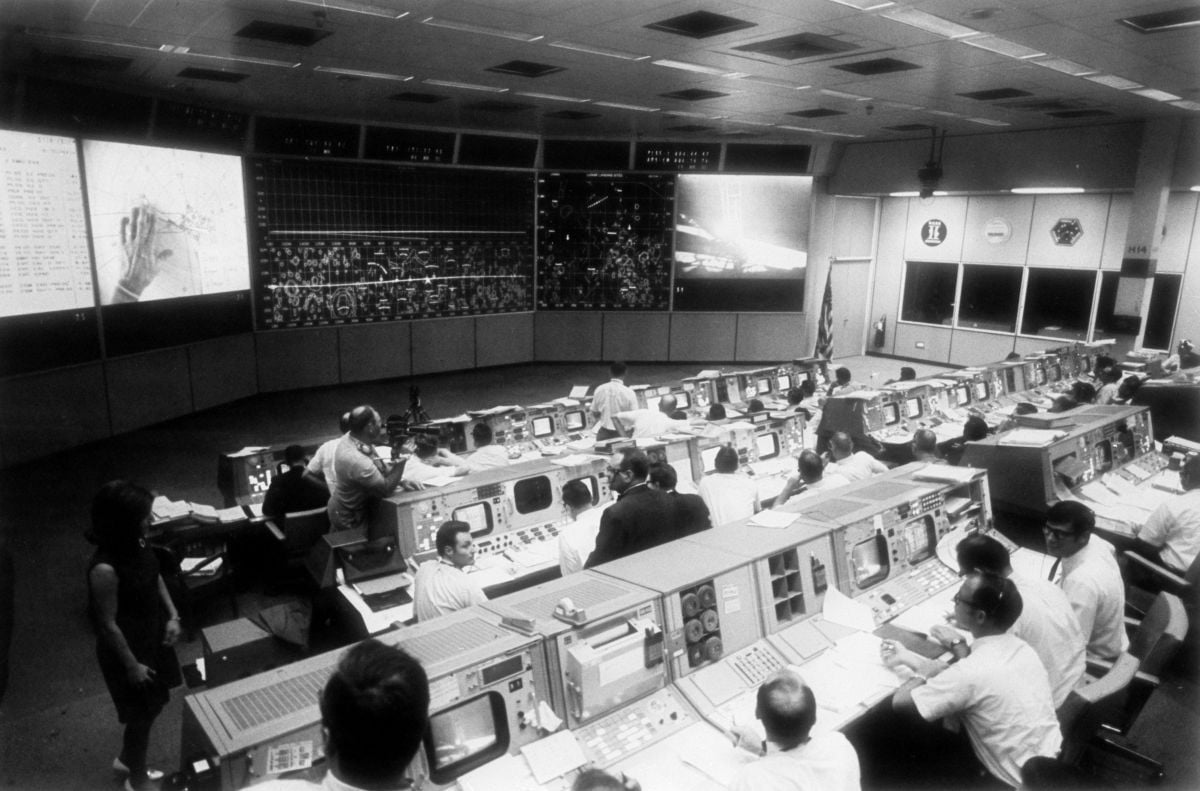

Meanwhile — Back at Mission Control…

While the Apollo 11 astronauts were walking on the moon, a trio of vigilant cameramen filmed the drama at Earth’s “nerve center.”

By Charles Loring

“We’re go!” Neil Armstrong says, “Hang tight, we’re go!” and the uglybeautiful, spiderlike lunar module Eagle veers to avoid a crater as the super-cool astronaut with the friendly porpoise smile guides it expertly toward the moon's surface.

In the windowless dimly lit Mission Operations Control Room on the third floor of Building 30 at NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center near Houston, 30 controllers sitting at four rows of gray computer consoles, monitor the hundreds of bits of data that came flashing up from gauges, dials and meters — and hold their breath.

Moving silently among them, Bob Bird, Lead Cameraman of a crew of three from Houston's A-V Corporation, trains the 9.5-95mm zoom lens of his Beaulieu R 16B 16mm camera on dramatic fragments of the historic scene. He shoots tense close-ups of faces peering into scopes, readouts from flashing wall screens, inserts of rotating pencils, tapping pens, the snubbing-out of cigarettes.

Then, as the coldly impersonal computers register lunar touchdown, that calm voice comes winging back from deep space: “The Eagle has landed!”

A barely restrained version of all Hell breaks loose in the Control Room. Cameraman Bird whips his lens about to capture the relief and elation of this momentous moment that can only happen once. It is on the film-locked in celluloid for posterity.

A-V Corporation, a commercial film company, is a prime contractor to NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center for audio-visual support and laboratory services, both still and motion pictures. It provides all motion picture services from script to screen, including script writing, editing and sound. Its photographic function is primarily in support of motion picture production. Engineering documentation is done by government cameramen, but A-V's cameramen have documented all of the manned space flights from Mission Operations Control for the past eight years, or since the beginning of the program. In addition, the company is contracted to NASA to produce training films, public affairs films, astronaut biography films, management briefing films, Congressional briefing films, etc.

In addition, A-V technicians process the overflow of motion picture footage at NASA's government laboratory on a follow-on (night shift) basis.

The three cinematographers who filmed the Apollo 11 activity in the Mission Operations Control Room (Lead Cameraman Bob Bird, Charles Turner and Jerry Bray) were there on what is euphemistically called a “noninterference” basis. In other words, they were working under some very tense conditions, shooting during the most critical phases of the flight. Therefore, the manner in which they conducted themselves was just as important as the skill with which they executed their photographic assignments. Had they gotten in anyone's way or caused the slightest distraction to any of the controllers, the flight operations director would have asked them to leave immediately. As it was, they executed their demanding chores without disturbing in any way the fine relationship that has existed between the A-V Corporation cinematographers and the NASA personnel since the beginning of the Manned Spacecraft flight program.

A-V Corporation's cameramen did not cover the Apollo 11 mission on an around-the-clock basis — not quite — but one or more cameramen were on hand to film all of the important highlights of the f I ight. Such key activities as the Lunar Orbit Insertion burn, Trans-lunar Insertion burn, De-docking, the lunar landing, the moon walk itself (“Extravehicular Activity”), Rendezvous and Trans-Earth Insertion burn were usually covered by two cameramen.

They photographed the busy “Capcom” (spacecraft communicator), the astronaut on duty who is the only one handling direct communication with the crew. They shot footage of flight operations director Christopher Columbus Kraft, who was in overall charge of the Mission Operations Control Room during the flight. They captured on film the individual functions of the 30 intense controllers at their consoles, and they would often cut away to the computercontrolled status board, with its readouts showing trajectories and other technical data.

During the more routine phases of the flight, one cameraman would hold the fort while the others took a breather. Lead Cameraman Bird was on duty from De-docking on through all of the lunar activities, including lift-off from the moon and Eagle's rendezvous with Columbia.

“After that I took about four hours off to go home and grab a shower and a couple of hours' sleep,” he recalls, “but the excitement was such that I cou Id hardly sleep.”

The Apollo 11 flight marked the first time that the Beaulieu R 168 camera was used inside the Mission Operations Control Room. Employed in conjunction with Eclair NPR and Arriflex cameras, it was equipped with a 9.5-95mm zoom lens, which was found to be preferable to the 12-120mm lens at the wide-angle extreme because of the “tight quarters” inside the facility. However, since the maximum aperture of the 9.5-95mm lens is F/2.2, it was necessary to run the Beaulieu to 20 frames per second in order to achieve an approximate exposure match between its lens and the F /1 .9 lenses used on the other cameras.

In addition to the Beaulieu, Eclair and Arriflex cameras used in the control room, a Canon Scoopic 16mm camera was pressed into service for filming inside the Lunar Receiving Laboratory. Due to quarantine restrictions, no professional cameramen were allowed inside this facility. So Scoopics were given to non-professional people under quarantine and, because of the camera’sease of handling and efficient automatic exposure control, they were able to procure some adequate useable footage.

No lip-sync sound was recorded at Mission Control during the Apollo 11 flight, simply because there was no real necessity for it — although a certain amount of wild sound was recorded for background. Flight control loops of the entire mission were recorded by another contractor in the form of a 30-channel track, and A-V has access to these tapes if it cares to lift any of the air-to-ground sound. Some of this is used to lay in alongside shots of the Capcom talking to the spacecraft, or vice versa, but there is no real need for sync sound since a majority of the action will be covered by narration in the final editing.

One of the most challenging aspects of filming functions of the Apollo 11 flight at the Manned Spacecraft Center is the fact that the amount of general illumination available in the Mission Operations Control Room is practically non-existent, due, of course, to the fact that any great degree of overall brightness would interfere with precise perception of data displayed on the many screens and cathode ray tube monitors in the room.

The light level varies from 7 footcandles to 16 footcandles in the brightest area, which is where the flight operations director is located. To further complicate matters, the available light is a mixture of incandescent and bluish fluorescent, the blend having a color temperature somewhere in the neighborhood of 4,000 Kelvin. These lighting conditions, however admirably suited to the prime function of the room, are clearly anything but ideal for color cinematography. Even when using Eastman Ektachrome EF 7241 (Daylight) color reversal film, with its rated speed of ASA 160, it is theoretically impossible to get acceptable exposure under such low-light conditions-and yet, as the result of a two-year period of experimentation, technicians of the A-V Corporation contracted to NASA have worked out a system of shooting and printing which produces fully timed release prints of exceptionally good quality.

“Our first step in the right direction was to decide on using the EF Daylight emulsion rather than the Tungsten,” explains William Robbins, A-V Corporation’s Vice-President in charge of NASA motion-picture production. “We tried both emulsions and found that the Daylight stock color balance is better suited to the bluish light in the room. Not only are the overhead fluorescents decidedly on the cold side, but each console has a cathode ray tube monitor -a miniature television screen-and these reflect a very blue light onto the face of the people sitting before them. Of course, the color temperature in the original is still a bit off. We tried, in the beginning, to correct for this with filters while shooting, but the filters cut down the light. Also, since the quality of the Iight varied somewhat from console to console it was almost impossible to get a consistency of color temperature by compensating with filters. So now we leave the filters off and do all of our color correction scene-by-scene in the lab.”

So much for color temperature — but what about the low light level problem? “There is the obvious remedy of pushing the film in development,” Robbins continues, “but we have found — as just about every other lab has — that if you push EF much beyond one stop, it starts to break up. You begin to get pretty bad grain and color shifts. So we expose wide open (at F/1.9), force the development one stop and then make a timed and color-corrected reversal master positive by contact printing onto A-wind Eastman 7388 release print stock, putting all the light we can through it in the printing. If the master is still a bit too dense, we can print it up even more at the release printing stage. In effect, we are ending up with a result as if the E F were rated at ASA 1,000. By using our Bell & Howell Model C printer with the additive light source, correcting for density and color balance at the same time, we’ve been able to maintain clear whites, good flesh tones and acceptable grain — in short, a very good product. What makes it possible is the use of the 7388 stock for the master positive, because it is of lower contrast than the ECO we were using in our early tests.”

Robbins gives much credit for the development of this technique to laboratory supervisor Frank Zehentner and color timer Ray Harris.

A-V’s three-man camera crew exposed a total of 12,800' of 16mm EF film in the Mission Operations Control Room during the spectacular Apollo 11 flight. Added to this is the footage exposed by the Command Module’s on-board 16mm cameras — plus kinescopes from the material sent back by television cameras in space.

Footage from these three sources has been combined to edit a dramatic 34-minute documentary called Apollo 11 ... For All Mankind, which supplements the official public affairs film The Eagle Has Landed: The Flight of Apollo 11, produced by the motion-picture facility at NASA’s Washington headquarters. In addition, an Apollo 11 Mission Report on film has been edited exclusively for the Manned Spacecraft Center. Excess footage has been catalogued and incorporated into the millions of feet of film on file in the Stock Film Library, which A-V Corporation maintains for NASA. This footage is made available to commercial producers and television networks.

Following the safe return of the Apollo 11 crew to earth on July 24, 1969, the American Society of Cinematographers extended honorary membership to Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins for their exemplary photographic work. The honor was accepted:

Images of the Earth taken from the moon by Armstrong and Aldrin were a beautiful realization of a whimsical illustration by Lewis Physioc, ASC that graced the cover of American Cinematographer in 1922 with the memorable line “Give Us a Place to Stand and We Will Film the Universe.”

You can download a complete PDF of this 1969 issue of AC right here, which contains a number of additional stories on the Apollo 11 mission, as well as coverage on Hollywood's fictional astronaut adventure Marooned and a detailed piece by visual effects expert Douglas Trumbull on his work in 2001: A Space Odyssey.