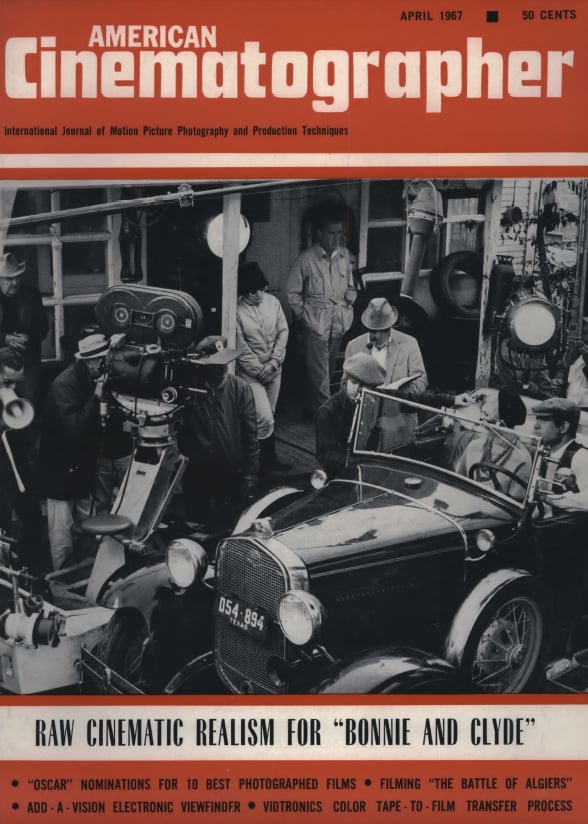

Raw Cinematic Realism in the Photography of Bonnie and Clyde

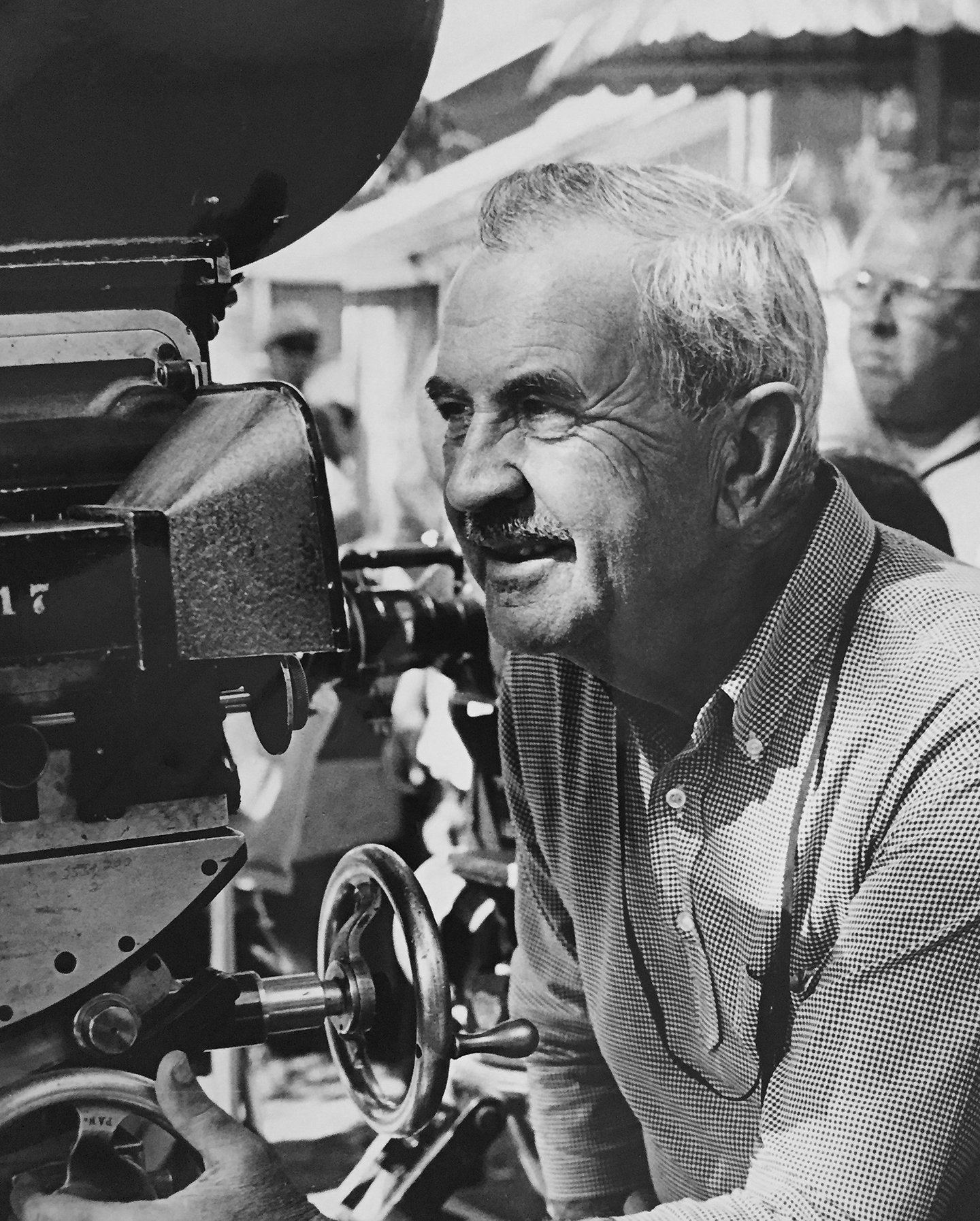

Burnett Guffey, ASC sought a sense of photographic realism for this stylized depiction of the famed outlaws’ life of crime.

Bonnie and Clyde sounds like the title of one of those saccharine soap-operas in which the clean-cut all-American boy marries the girl-next-door, after which the two of them go strolling off hand-in-hand into the sunset — living proof that togetherness can triumph over crabgrass.

In actuality, Bonnie and Clyde is the title of a brutally violent new Warner Bros. film which re-creates the Depression-ridden 1930s when bank robber Clyde Barrow and his cigar-smoking sweetheart Bonnie Parker not only held the sheriffs and bank tellers of the Southwest in terror, but also hit almost daily headlines with their daring, often reckless and frequently pointless criminal exploits.

In the filming of Bonnie and Clyde the name of the game was “realism,” and to achieve that visual effect on the screen in color, veteran cinematographer Burnett Guffey, ASC, was assigned as Director of Photography. He had captured a rugged semi-documentary effect on film in his striking black-and-white cinematography of the Academy-nominated King Rat last year, but this signaled his first attempt to arrive at a similar effect in color — and the challenge was a respectable one.

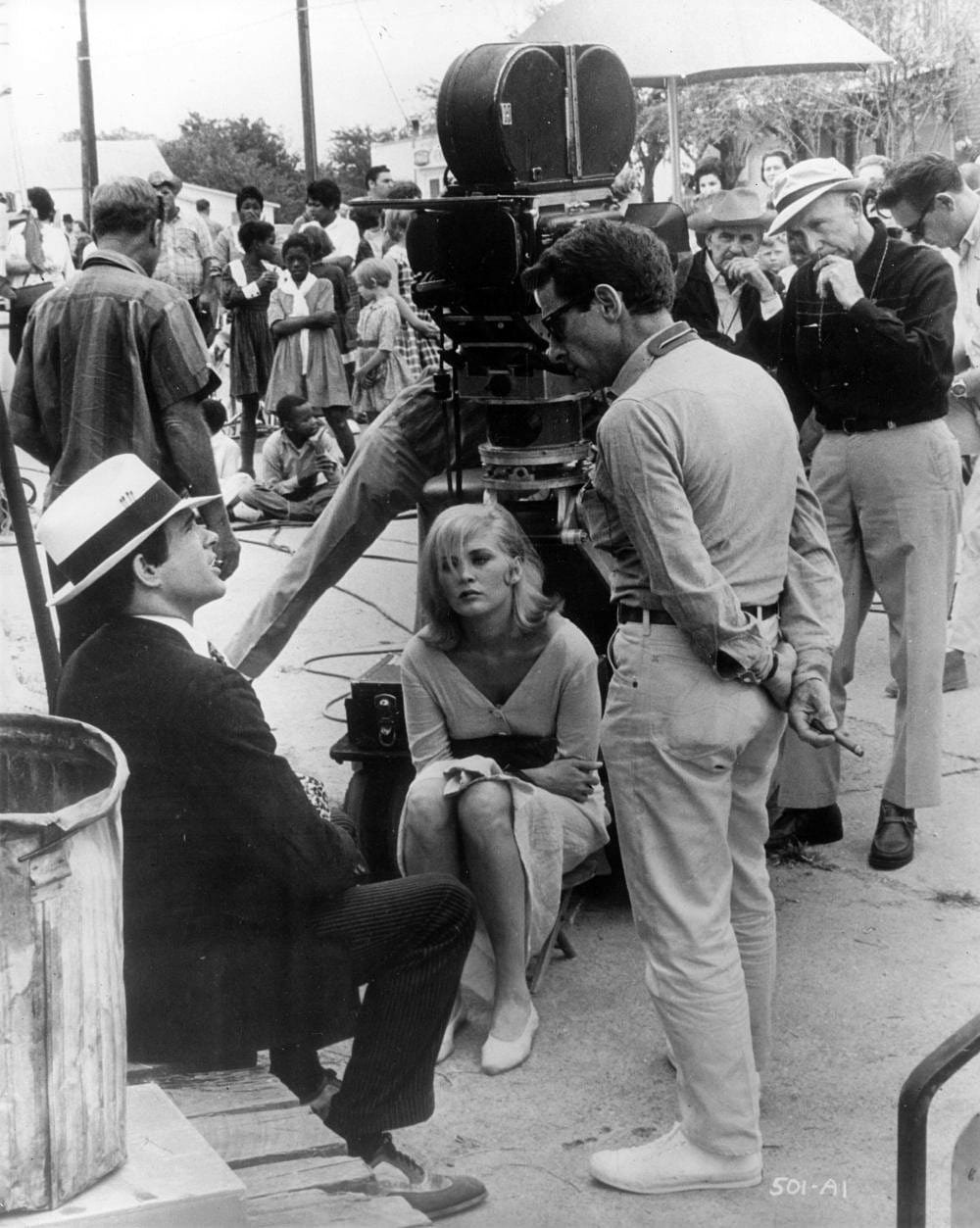

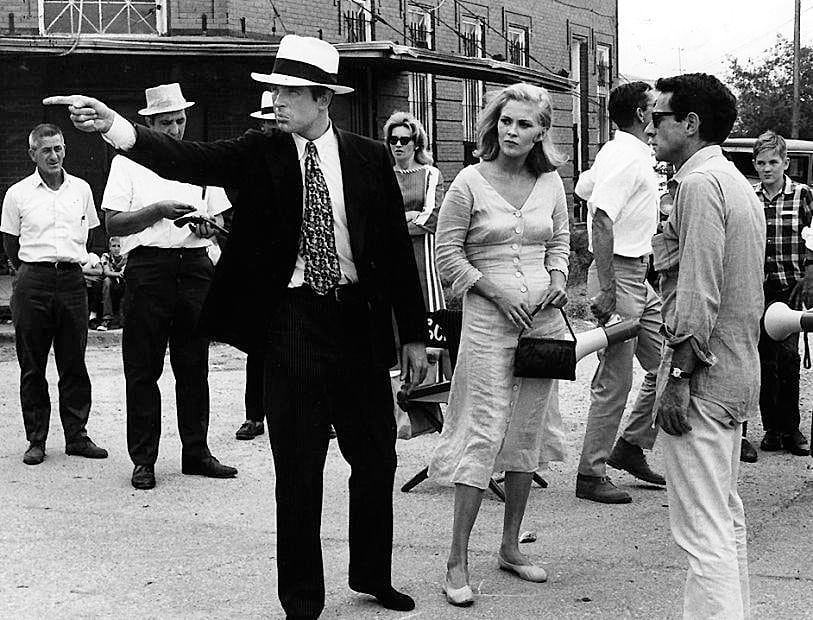

“The director, Arthur Penn, wanted his film to be as real and untheatrical as possible,” Guffey comments. “The producer, Warren Beatty — who was also the star of the film — shared his point of view. They were out to get stark realism on celluloid. Nothing was to be beautiful. Everything was to be, you might say, harsh — and that’s the way it was through the whole picture.”

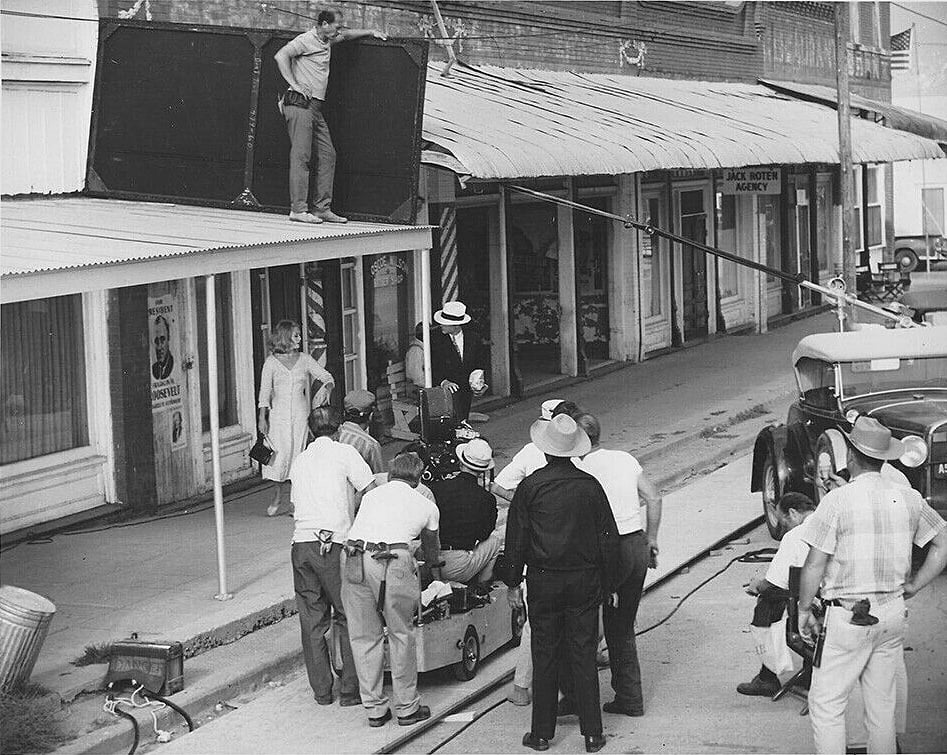

In the interest of such realism the decision was made to film as much of the script as possible in the actual locales where the true-life outlaws of the title had held sway more than 35 years before.

The Cinematic Invasion of Texas

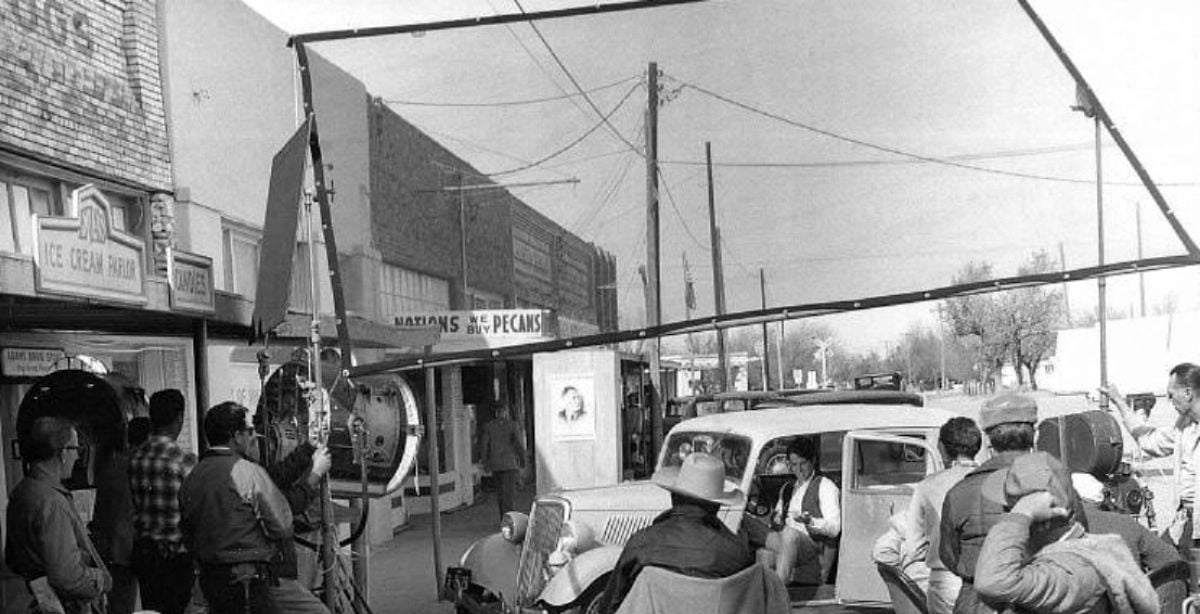

The Bonnie and Clyde unit spent 10 weeks in northeast Texas filming in a series of small towns near Dallas — Rowlett, Maypearl, Venus, Ponder, Pilot Point, Garland, among many others — which had once been visited by Clyde Barrow and members of his gang for their assorted raids on banks, grocery stores and gasoline stations. In every case the small communities — populations never more than a few hundred except for sprawling Garland — had remained almost unchanged since the Clyde Barrow days in the early 1930s. In Texas the area is called Clyde Barrow County even today.

With the company as it “toured” the succession of small crossroads went a retinue of some 20 period cars, 1930-1934 models of Stearns-Knights, Hupmobiles, Star Durants, Jewetts as well as durable Fords, Chevies and Dodges. These were acquired on the location site for several hundred dollars, refurbished with tuned-up motors and after their “acting chores” were completed in the movie — Clyde Barrow stole more than 50 different vehicles during his 3.5 years of raiding — were sold at a profit to vintage vehicle fanciers.

Three banks once robbed by Clyde Barrow and revisited by Warren Beatty and his gang — Pilot Point, Red Oak and Venus — are still standing. All of them, closed during the Depression, re-opened for “business” as the cast went about the business of looting them anew.

Dallas served, too, as the background for such disparate places as Arcadia, La., Dexter, Iowa, and Joplin, Mo. In fact, the Joplin Chamber of Commerce took offense at the fact that producer Beatty had found an aged and somewhat crumbling neighborhood in Dallas which resembled the slums of Joplin in the ’30s. Lemmon Lake, a privately owned preserve, a few minutes from downtown Dallas, served as the celebrated (or infamous) “ring of fire” where over 100 deputies in Dexter, Iowa, encircled Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, Buck Barrow and his wife Blanche and wheelman “C.W.” in 20 minutes of drumfire and hell. In actual life Buck was killed, Blanche captured and Bonnie and Clyde severely wounded — their first drastic encounter with an angered law.

To move the Bonnie and Clyde contingent across the country from “East Texas to Indiana” in a recreation of Clyde Barrow’s robbery meanderings took the logistics of a Napoleonic army on the move — 20 vehicles including a dozen trucks for props, wardrobe, special effects, cameras, sound equipment and, finally, an entourage of 70 which included actors and technical staff. The company was up daily at 4:30 and filmed uninterruptedly for 10 weeks with only one single day spoiled by inclement weather.

In addition to the rolling stock the company also carried an arsenal of several hundred guns, including such period weapons as World War I machine guns, rifles, pistols, revolvers, and over 30,000 rounds of blank ammunition. The “ring of fire” consumed almost 7,000 blanks for three days of the Dexter, Iowa, shootout.

Casting for extras, atmosphere people and bits was handled according to Arthur Penn’s “Stockbridge Plan,” an interesting innovation which the director used in the summer theater at Stockbridge, Mass., where he has periodically worked. It involved a talent scrounging tour by casting director Peter Maloney who visited the various towns to be used later by the filming crew. Here, he contacted a usually friendly City Clerk — invariably a woman — who called her friends on the phone and told them to show up on such and such a day to be actors in a Hollywood movie! And they all turned out well playing themselves as they might have been 35 years ago! Six of the most interesting pieces of casting were six truants from a Dallas Reform School who were lads in the “ring of fire” sequence playing deputy sheriffs. In 1934 teenagers were hastily deputized to bring shooting irons for the shootout against the Clyde Barrow gang.

Lighting Style to Fit the Subject

In arriving at a photographic style to complement the stark character of the story, Director of Photography Guffey kicked over some of the traces usually regarded as sacrosanct in professional color cinematography. “We did some things that might be regarded as wrong photographically, but they created the atmosphere of realism that was wanted,” he explains. “We had agreed in advance that there would be no ‘slick’ Hollywood photography, as such, in the picture‚ so we used no fill light at all in any of the sequences. There was just a key light, with the other side of the faces being allowed to go dark.

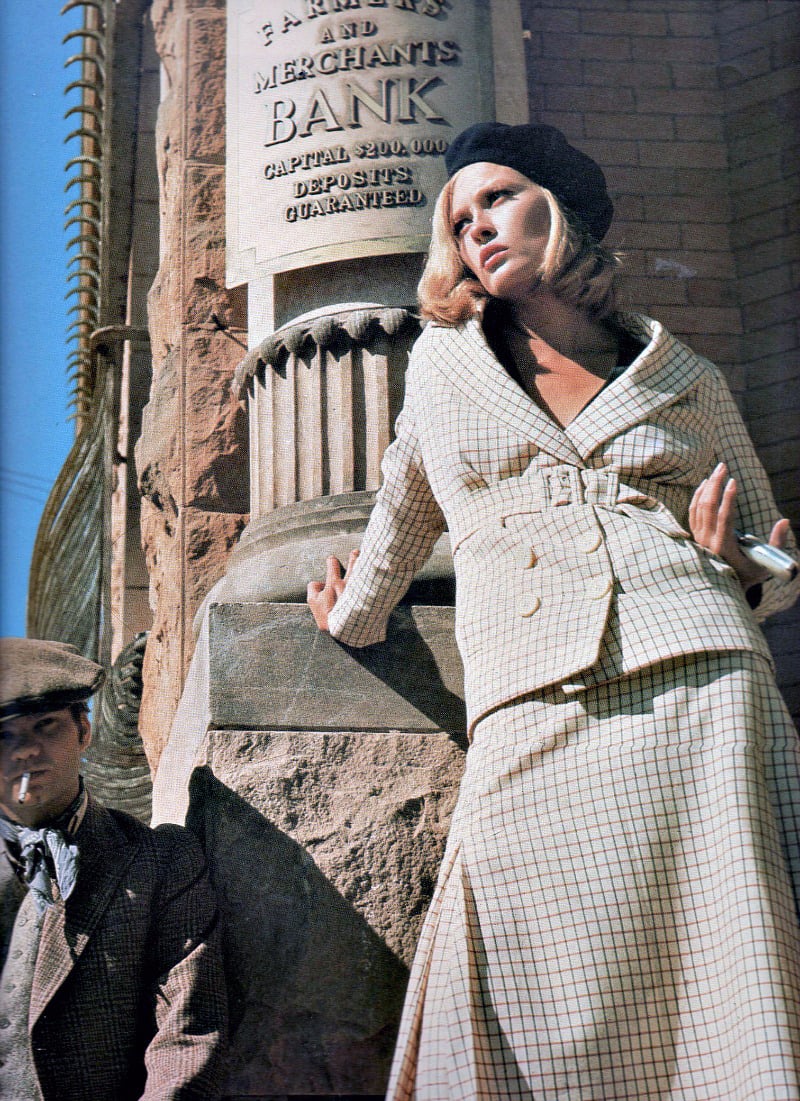

“No attempt was made to glamorize any of the people with soft, diffused lighting. Even the female lead, Faye Dunaway, was shot with no diffusion whatsoever. She wore very little makeup, but she was not too hard to photograph because she has a good face. However, no concessions were made for her lighting-wise. If a light source was established as coming from the side, I let it hit her from the side, with the other half of her face going dark. The result has a raw quality that might be called “documentary” — but we got some striking footage and it looks real all the way through.

Because all of the natural interiors and the few sets built on the sound stage had ceilings, it was impossible to use back-lights or kickers for separation. Guffey worked around the problem by lighting the background walls either darker or, in a few cases, lighter than the actors playing in front of them.

As a hedge against possible inclement weather, the company had rented a soundstage in Dallas from an organization that uses it for shooting commercials. A few simple cover sets — motel rooms and such — were built on the stage so that the company could move inside and continue shooting if the weather went bad. Except for these scenes and a few complicated process shots that had to be filmed in Hollywood, all of the interior sequences were photographed in actual buildings. The main problem consistently encountered was that of finding enough space for the equipment needed to execute some of the intricate moving camera shots required by the director.

“Arthur Penn is a very creative director who is a firm believer in moving either the camera or the actor,” says Guffey. “Many of these moves covered almost 360 degrees, but in the cramped quarters of some of those small rooms I occasionally had to ask him to leave me one small space where I could put some lights — and he would do so.”

Camera movement in these tight spots was made possible through the use of the tiny Italian Elemak dolly which has a hydraulic center-post for the camera, but no platform — simply a seat for the operator. Where floors were smooth it could operate without tracks like a crab dolly. Otherwise plywood had to be put down and painted to match the floor or camouflaged with carpet.

Plagued With Daylight

Since the main preoccupation of the real Bonnie and Clyde had been that of robbing banks, there are several sequences in the picture depicting bank robberies. All of these were shot inside actual small town banks, a few of which were the very same establishments plundered by the daring crime team.

“We photographed both the exterior and interiors of these banks,” Guffey recalls, “and our main problem was that of being able to get the actors and camera equipment in with enough room left for enough lights to illuminate the interior to balance with the exterior seen through windows and doorways. Most times, when you shoot in actual interiors, you can simply cover windows with sheets of 85-filter material — and there’s no problem. But in almost every case we had to show entrances and exits because the characters would burst into a bank and say: “This is a holdup!” As a result we had some extreme problems in balancing the blue light from the outside with the incandescent light used inside. It wasn’t practical to use arcs because they are too big and would have smoked up the place — so I had to shoot it as an interior and find some way to filter out the blue daylight. I’m sure most cameramen have come up against the same problem but it’s a challenge each time you encounter it because each situation is different and you have to play it as you go.”

The obvious solution of using Macbeth or dichroic filters on the interior incandescent lamps to balance with daylight was ruled out because of the light loss (approximately 64% and 30%, respectively) which results when such filters are used.

Instead, special, large heavyweight sheets of plastic 85-filter material (approximately 6x8 feet) were imported from Chicago and set in place outside of the bank entrances. Mounted in frames camouflaged with doorjambs and such, these filters were sturdy enough so that they would not shake in the wind. For extra-large doorways, two or more sheets were butted together with thin strips of transparent tape.

Quartz-iodine in the Tight Spots

Although Guffey used standard Senior and Junior incandescent spot units as key sources for lighting the actors in location interiors, he would occasionally utilize quartz-iodine units for background illumination. These compact, high-intensity lights could be easily hidden behind furniture, kitchen stoves, etc., when close quarters ruled out the use of larger units.

Battery-operated Professional Sun Guns were used inside of cars in the many actual running shots that were made in this manner, without resorting to process photography. 26-Blue gelatin filters were used in front of the Sun Buns to correct their color temperature to that of daylight. Though such filters are flimsy and tend to fade rather rapidly, they produce much less light loss than glass filters and are expendable.

Inevitably, with these automobile shots filmed during the day, there was the problem of balance between the interior and exterior light. Since it was impractical to cover the car windows with any sort of filter material, Guffey’s only recourse was to effect a compromise in exposure. He split the difference between the outside and inside so that, in effect, the exterior was slightly over-exposed, while the interior was slightly under-exposed.

All of the running car shots were filmed with a handheld Arriflex. In some cases the operator would crouch in the back set of the car in order to get shots of those riding up front. At other times he would ride one of several outrigger mounts which the grips constructed on the outside of the car.

Night-for-Night Heavy Duty Lighting

The climactic sequence of the picture, in which Bonnie and Clyde are surrounded in their hideout by police and engage in a furious shoot-out with the law, was photographed night-for-night and was so intricate that it necessitated sending to Hollywood for an extra crew of electricians to handle the many lights involved.

Approximately a dozen police cars approach in darkness the decrepit motel (an actual location structure) in which the outlaws are holed up. At a given signal from one of the officers all the cars run on their headlights, which are beamed toward the motel. A furious gun battle ensues during which Bonnie and Clyde shoot their way out and escape.

“Color in itself sometimes detracts from realism because it comes out pretty whether you want it to or not.” — Burnett Guffey, ASC

The area involved included a deserted stone motel, the aggregation of police cars and a stretch of country road — all in all, a substantial plot of real estate.

Guffey lighted the scene with a combination of Brute arcs and incandescent units. The headlights of the cars had been rigged with battery-operated extra powerful lamps so that they would register brightly in the scene. However, they could not be used for actual photographic illumination of the scene because they were so bright that they would run the batteries down in approximately two minutes. Consequently, studio lamps had to be hidden between the cars at a suitable height to simulate the beams from the headlights.

Where the headlights were supposed to hit, Guffey gave the scene a normal exposure — but where there were no lights hitting he left the areas very dark and sketchy, with perhaps just a dim light hitting the branches of a tree.

A Gamut of Lenses

In filming Bonnie and Clyde, Director of Photography Guffey used a variety of lenses ranging in focal length, incredibly from 9.8mm to 400mm. The 9.8mm ultra-wide-angle F/1.8 Kinoptik lens helped solve some of the problems attendant to shooting in very small rooms, plus providing dramatic perspective for certain effects.

In describing his use of the 400mm telephoto lens, Guffey explains: “We used it for a host of two men sitting inside a cafe supposedly plotting how they were going to trap the Barrow gang. We set up the camera about 100 feet away from the cafe and pointed the lens through the window to frame the two men as they talked. We then brought them outside and followed them along the street — all in one shot. There was only about one foot of depth of field, which meant that it took some very careful follow-focusing through the reflex finder of the Arriflex camera — but the scene turned out well.”

An Argenieux 25mm-to-250mm zoom lens was brought into play, though sparingly, for shock impact as, for example, when a policeman gets shot and there is a sudden zoom to a closeup of his face spurting blood.

Asked about efforts to subdue the color in a grim subject like Bonnie and Clyde, Guffey replied: “Color in itself sometimes detracts from realism because it comes out pretty whether you want it to or not. We tried very hard to subdue the color in this picture mostly through the handling of the sets — dirty motel walls, old bank buildings and that sort of thing. Arthur Penn attempted to use color without pointing it up as color or glamorizing it in any way, because he felt that this would create a more convincing effect of realism. I think he succeeded because this is one film that can never be called ‘pretty.’”

The film was nominated for 10 Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Cinematography — with Guffey winning his second Oscar for his outstanding camerawork in the picture.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

For access to all 100 years of AC reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.