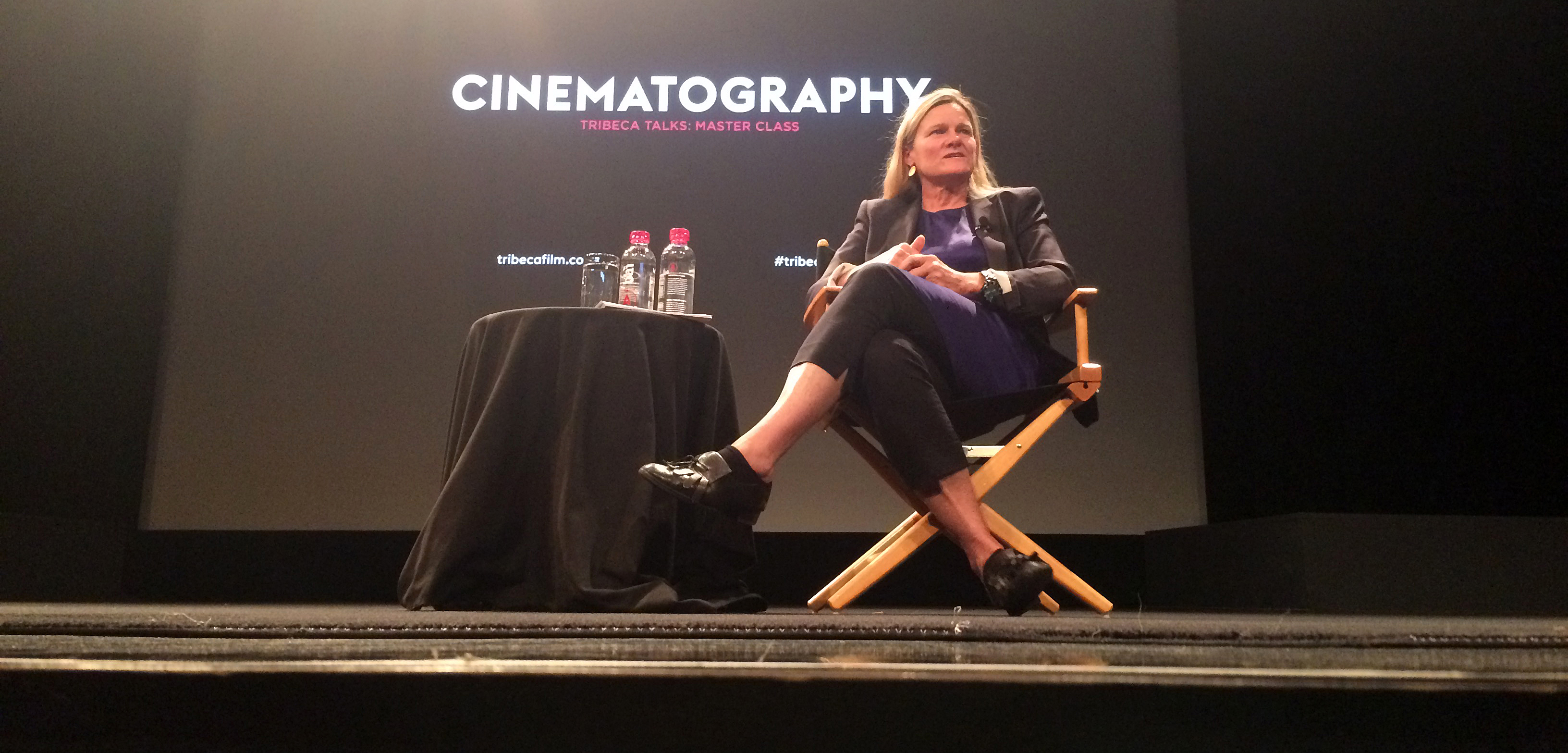

Ellen Kuras, ASC on Story, Intentions and Intuition

The award-winning cinematographer shared her big-picture thoughts on meaning making at the Tribeca Film Festival.

The award-winning cinematographer shared her big-picture thoughts on meaning making at the Tribeca Film Festival.

By Lauretta Prevost

Ellen Kuras, ASC has been photographing motion pictures as a cinematographer since 1989, and, among other honors, earned the Sundance Film Festival’s Award for Excellence in Dramatic Cinematography three times — for Swoon, Angela and Personal Velocity: Three Portraits.

As part of the recent 2017 Tribeca Film Festival, Kuras gave a master class on her chosen craft, drawing on the experience she gained while shooting the narrative features Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Blow as well as the documentary The Betrayal as practical case studies of her humanistic and story-driven approach to cinematography.

Kuras’ class mimicked her approach to filmmaking, making it a heartfelt and personal hour. And her main messages were clear: Think about the story that you are trying to tell and how you are creating meaning. “You have to know what you’re talking about,” she said. “I know so many people who shoot and they don’t know the story.”

As a student at Brown University and NYU, Kuras focused on social anthropology as well as film studies, driven by a desire to know the people on whom she was turning her lens. She recalled once hiring a cinematographer for a documentary project and getting back beautiful footage that “didn’t move me.” Kuras encouraged the Tribeca Fest attendees to appreciate how filmmaking is a form of propaganda, how filmmakers tell stories they want the audience to believe in, and how decisions made during the filmmaking process create and impact meaning.

Preproduction should be the time to delve into these questions, and to think about whose point of view from which the story should be told. “As soon as you start having these discussions on set you’ll lose time,” Kuras said, “and you’ll lose your mind’s eye.” In preproduction on narrative films, Kuras asks for four days with her director’s undivided attention so — more important than choosing coverage — they can talk out the intention behind each scene.

With documentary projects, Kuras stressed the importance of thinking on your feet from the perspective of the story you are aiming to tell: Where will you stand? Do you allow the person to walk into darkness and what does that say? Every shot should have a story and a reason. “As an audience,” she said, “everything we see on screen affects us.” For Kuras, the least interesting coverage is the classic master shot combined with angle on one character and matching reverse angle. As a case in point, Kuras delved into Eternal Sunshine (AC production story here), which combines scenes from reality with an allegorical, memory-based world. “We were in a person’s brain and I realized the form of the film had to be in that context: Handheld, with glimpses of tunnel vision.”

Director Michel Gondry came into the project with strong ideas, such as not wanting to use traditional movie lights. “I thought about how I could shape the way I work to what he wanted to do,” Kuras shared, “and how to understand the meaning behind what he was trying to say.”

Gondry didn’t want the film to look too neatly lit, and while they did end up using film lights, once Kuras understood Gondry’s intention she could adjust her approach. “As filmmakers, if we think of ourselves as problem solvers,” Ellen reflected, “it becomes different than stomping your feet and saying, ‘We can’t do this.’”

Kuras touched briefly on gear. It’s popular to consider prime lenses superior to zooms, and a geared-head tripod superior to a fluid head. But for Kuras, the tool should serve the story. A geared head is preferable as it feels like an extension of her body. Zoom lenses appeal to her as she can do a little push in when she feels it’s right, as opposed to needing to plan out the move with a dolly grip. She recalls meeting with Sven Nykvist, ASC. “Sven said he used zoom lenses all the time, and that I should use whatever I feel — to follow my intuition,” Kuras recalled. “Sven said that if anyone questioned me, I could say, ‘Sven gave me permission!’”

“I encourage you to follow your inner voice,” Kuras told her appreciative audience. “That’s where your point of view comes from, and it’s commensurate with your life experience and your craft experience.”

The Betrayal is a documentary Kuras directed and shot over two decades, focused on a Laotian family relocated to Brooklyn. During the Vietnam War, the neighboring country of Laos had been heavily bombed by the U.S. Air Force — a relentless attack referred to as the “secret war,” based on U.S. officials’ denials and American public indifference. “With film, you can tell a story that’s based on a real situation and have people be moved by it,” Kuras explained. Looking to use archival material in a personal way, she projected period propaganda films on a wall and re-photographed them.

Reflective of how important Kuras believes truly understanding the subject matter is, the filmmaker learned Laotian so she could better understand the worldview of elder members of the family.

Based on actual events, Blow is a biopic following the highs and lows of cocaine smuggler George Jung. As the story spanned the 1950s to the 1990s, the primary cinematic challenge for Kuras was to make a film with five distinct periods that didn’t look like five different movies. Extensive period research inspired her to put together a look for each period based on the filmmaking technology available during each respective era.

Regarding the director-cinematographer relationship, Kuras believes the most essential aspect is trust: “It is so important for me that the director know I am watching out for them, trying to get into their heads and enhance their story. I don’t bring my own ego into it other than my learning experience.”

Kuras considers filmmaking a collaborative process, and doesn’t think of the cinematographer’s role as a top-down hierarchy. “Treat everyone with respect,” she shared. “You don’t have to be an asshole to be good.”

Filmmaker Lara Sfire attended the class: “I appreciated Ellen talking about cinematography as simply another tool in the storytelling process,” she reflected, “Speaking about it in philosophical, psychological, and anthropological terms instead of technical terms.”

Fellow audience member producer Zack Wilson added, “It's a nice reminder, as it's easy to get caught up in the minutiae of the latest sensors, pixel counts, color spaces or wireless gadgets.”

In short, the main take aways from Kuras’ Tribeca talk were to think about the story you are trying to tell and to let your shot selection and technical choices come from how best to serve that meaning; the importance of understanding the director’s intention; and to follow your intuition. And if that requires making an unpopular technical choice or shooting the whole movie on a zoom lens, Ellen Kuras said you could do it.