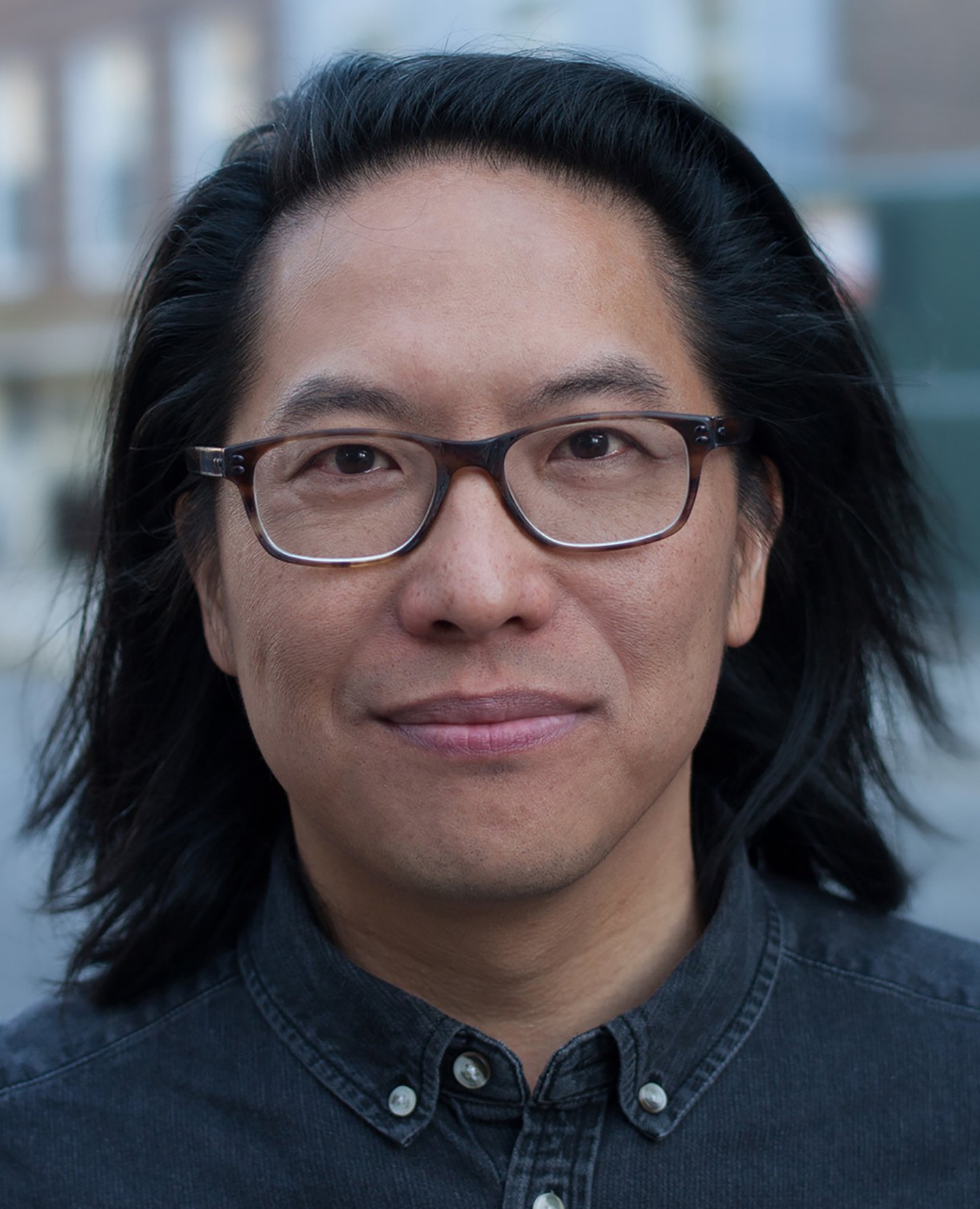

Crime + Punishment: Exposing Corruption in the NYPD

Online Exclusive: Filmmaker Stephen Maing discusses how he employed hidden cameras, drones and other visual methods to reveal the unseen discriminatory policing practices in the nation’s largest police force.

Online Exclusive: Filmmaker Stephen Maing discusses how he employed hidden cameras, drones and other visual methods to reveal the unseen discriminatory policing practices in the nation’s largest police force.

Cary Grant waits for Deborah Kerr on the Empire State Building observation deck in An Affair to Remember. Thirty-six years later, Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan meet on the same observation deck in Sleepless in Seattle. Kevin McCallister, played by Macaulay Culkin, reunites with his mother at the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree in Home Alone 2. The Ghostbusters are cheered on the streets as heroes after slaying the towering Stay Puft marshmallow man in Ghostbusters.

Iconic and picturesque, this is how Hollywood depicts New York City — the most populated city in the United States — which is used as a backdrop in film and television more than any other city in the world. But, for many New Yorkers, the reality of daily life is a stark juxtaposition to the romantic cinematic portrayals, and the city is most known for skyrocketing costs of living, gentrification and predatory policing practices targeted at minority communities.

At the 2014 New York Police Department Police Academy graduation, Commissioner William Bratton makes an impassioned speech about the work the NYPD has done in making New York City a safer place to live. They have cleaned up the streets, addressed the high crime areas and made the city a shadow of its former, dangerous self. The thousands of officers in the arena erupt into applause as the new cohort of graduates is ushered onto the force and the Commissioner announces the Department’s new mission to “protect our children.”

With more than 38,000 uniformed officers and 50,000 total employees, the NYPD is the nation’s largest police force and even bigger than the nation-wide FBI. Filmmaker Stephen Maing’s new documentary Crime + Punishment focuses on 12 on them — whistleblowers — who come to be known as the “NYPD 12.” The film follows their story as they attempt to bring a class action lawsuit against the NYPD for its racially discriminatory policing practices, blatant disregard for the state’s anti-quota bill and systematic retaliation.

But Maing, who served as the documentary’s director, cinematographer, co-editor and producer, is quick to acknowledge that this story is not new. Even though the film focuses on 12 officers, “they come from a long tradition of other cops who have tried to blow the whistle on this level of corruption and the use of quotas in the NYPD,” Maing says. Many officers in the film, he adds, sought media attention to bring awareness to their ongoing plight. Yet, despite some coverage, many Americans — including New Yorkers — were unaware or apathetic.

“There was this great irony to me that so much was unfolding in plain sight and yet it was totally invisible to the city and the nation,” says Maing. “Here we are a nation totally divided on race and policing — easily the most contentious issue being debated daily on social media feeds — and here was a group of individuals who were fighting the fight of a century to expose and ultimately try and improve our understanding of how to address structurally discriminatory policing practices — and nobody was paying attention.”

What the story needed to grab people’s attention and make them care, Maing thought, was a “human-scale narrative” that drew its strength from visuals. “Looking isn’t always seeing,” the filmmaker sates. “The images are the first and last place that have a chance to activate the humanity of the moment. If you don't do it in the visual language, it's not going to happen anywhere else in the process.

“I really wanted this to be a very different kind of cinematic experience, and one that could morph between genres — be investigative and cinematic, unfold like a fiction film and then also break the fourth wall in an unexpected cinéma vérité style. But, at the end of the day, the film is rooted in humanistic information that doesn’t just photograph the information and evidence, but sets out to visualize something more unseen that was happening to these people.”

One of these “unseen” aspects was the retaliation officers faced when they did not meet arrest and summons quotas, which — according to New York State Senate Bill S2956A — is illegal. Passed in 2010, the bill prohibits “quotas for a ticket, summons or arrest authorized by any general, special or local law.” This is perhaps best demonstrated in a scene with NYPD Officer Sandy Gonzalez of the 40th Precinct — the southernmost precinct in the New York City borough of the Bronx.

In the winter of 2014, Gonzalez stands by himself on a street corner in low 30°F weather. He wears his uniform and an arctic trooper cap, and he has been instructed by his superiors to stand there for the entirety of his eight-and-a-half-hour shift and do nothing. This is his punishment for low summons and arrest numbers — four years after the New York State Senate passed the anti-quota bill.

From the opposite street corner, Maing captures on camera as Gonzalez’s supervisor arrives on the scene and instructs him to remove his arctic trooper cap, claiming that it is in violation of the uniform code. The cap can only be worn when the temperature is under 32°F, and despite the low-30s temperature, Gonzalez’s supervisor says that the forecast predicts a high of 38°F, and the cap must be removed. As this exchange happens and as Gonzalez stands on the street corner for his entire paid workday, calls are crackling out of his radio, but the patrolman is not allowed to address any of them.

“Documenting this full shift where taxpayer dollars are paying for this cop to be punished like a child on a street corner was the most astounding thing I've ever seen,” remembers Maing. “That shoot really formalized this feeling that I had to follow this story.”

Over four years, 350 shooting days and 1,000 hours of footage, Maing tracked Gonzalez and the rest of the NYPD 12. Throughout the course of the production, the filmmaker captured many delicate — and potentially dangerous — situations, and some of the film’s most damning visuals were caught by hidden cameras. In every scenario, it was at the forefront of Maing’s concerns to protect his subjects. “Something I learned when I was making a film in China about citizen journalists pushing back against government-mandated censorship [High Tech, Low Life] was that in these sorts of politically sensitive situations, you take all of your security and risk cues from your subjects because they usually know best. Their comfort level has to be first and foremost and determinative of how far you go with the filming…. I was constantly thinking and worried about how we execute this film in a way that would ultimately help and not hurt the NYPD 12.”

Often, an officer would call Maing and inform him of a situation that would be prudent to the film, and Maing would assemble as quickly as possible to capture the situation as it unfolded. “For me, the greatest challenge of this film was finding out something urgent was happening and scrambling to quickly whip up a filming plan and then mobilize to document it. I felt it’d be a great public disservice to have such increasingly deep access to these individuals and possibly not be able to do justice to the telling of their story.”

In the case of capturing Gonzalez on the street corner, the patrolman called Maing and informed him that he was being retaliated against, and Maing immediately headed to the Bronx. “Sandy was very encouraging of me to capture this moment because, for him, this is something that nobody would ever believe he was going through. But being put on a retaliatory foot post was something that he had experienced many times. For him, this was the greatest insult and dehumanizing waste of city resources — a cop who joined the force to try and protect and serve the community being told that he can't address any crime that is unfolding because he's going to stand there and be punished all day.”

One of the biggest challenges Maing faced was “trying to create an unofficial narrative that wasn't reliant on asking for permission from the Department.” He adds: “There's a reason why we don't often see very intimate narratives about the candid experiences of active duty law enforcement — because they're not sanctioned to speak to journalists or filmmakers. And when they are, it’s more often than not that very particular individuals are chosen so that a certain kind of message can come across.”

But showcasing the perspective of police retaliation wasn’t enough, Maing says. To accurately portray the depths of the problem, audiences needed to see those most directly and devastatingly affected by illegal and discriminatory policing practices. Enter: Manuel Gomez.

Gomez — a former NYPD officer and now private investigator — discovers a pattern of falsified arrests in minority New York City neighborhoods. The documentary follows as he works to collect evidence to exonerate 17-year-old Pedro Hernandez, whose multiple falsified arrests kept him incarcerated for a year in Rikers Island — New York City’s main jail complex, which has a reputation for abuse, violence and neglect. Gomez discovers that the officer who was responsible for all of Hernandez’s multiple wrongful arrests was promoted after he exceeded the monthly arrest quota three times.

The film then poses the question: Is this the consequence of officers pressured to meet quotas or face retaliation?

Gomez’s revelations reinforce the testimony of the NYPD 12 and shed light on how these discriminatory practices have impacted the city’s cost of living and gentrification. “There's a kind of ruthlessness to how public policy and policing practice is more in service to so many other of the city’s agendas,” Maing says. “‘Cleaning up the streets’ is code for ‘Making room for development and gentrification.’ ‘Addressing high-crime areas’ is another way of saying, ‘We're going to go into minority communities and look for low-level infractions that might be a pretext for finding or creating a higher level of arrestable engagement.’”

The majority of these falsified arrests are ultimately dismissed, but the film showcases how the stigma and consequences attached to those arrested and incarcerated can’t be as easily erased. “On a daily basis, we see the marginalization of black and Latino people in this country who are criminalized and caught up in the criminal justice system,” Maing says. “As a result, so much can be derailed — education, employment and simply one's personal growth when you're forced to keep showing up to court to deal with serious or falsified charges. And it’s immensely difficult to extract oneself from that kind of situation.”

To create a cohesive narrative, Maing employed aerial photography as a means of transition. “[The mapping device of aerial photography] is a vital part of the visual language that helps structure the entire conceit of the film,” Maing says. “In a loose sense, it creates this [sensation] that we can’t understand the big picture of the political or policy impact of any story without getting as close to the human experience as possible. Both are vitally important and have to be simultaneously experienced. The aerial photography was the one way I felt like I could suggest that this was a systemic view of the criminal justice system in New York. It allowed me to create this multi-narrative structure in the film and also be this very literal way of saying there is, in a lot of ways, a sublime disconnect between our macro understanding of contemporary policing issues and the invisible micro, ground-level narratives going on down below into each precinct.

“The structure is designed around these cascading stories that dovetail into each other to create a corroborating affect. Then, at every sky-high transition to a new precinct, we’re given a moment of pause where these unseen connections can come to life. It enables us to drop down into a different character with a totally different but related experience so that ultimately this mosaic of law enforcement and the street-level collateral damage not only reinforces a collective sense of storytelling, but, journalistically, I could spread the burden of liability so that no singular character would have to bear the entire brunt and weight of the claims being communicated in the film.”

Maing operated the Canon C300 with Canon EF 24-70mm, 70-200mm f/2.8L and Rokinoh 35mm and 50mm prime lenses, and most of the film was shot handheld. The filmmaker primarily opted for natural lighting, stating, “Having worked as director of photography on both fiction and non-fiction for many years, I’ve long felt that subtle shifts in camera position can often maximize the use of available lighting. The high sensitivity of current sensors and histogram are our best friend — which I always track. I like to keep my ISO below 8000 but also really love images that embrace both true black and fully exposed practical sources.”

Operating as a “one-man band,” Maing mostly filmed alone, though a few sequences — such as the NYPD graduation, promotional ceremony and community meetings — employed second and third camera units. The filmmaker meticulously storyboarded the aerial photography, which was conducted on the DJI Inspire 2, and Alon Sicherman and Micah Dickbauer served as drone operators. The project was co-edited by Eric Daniel Metzgar, and Maing performed color correction at PostWorks in New York.

Reflecting upon why he felt a documentary was the best medium to tell this story, Maing offers: “I think people need nuanced documentary storytelling to process certain kinds of information in a way that other mediums not always can [provide].” A visual story, he adds, would be the strongest. “I felt that if the cinematography could feel very intimate, rooted in deep human observation, and perhaps at times blur the lines of fiction and non-fiction, it would be an important key to unlocking our understanding of what these police officers and community members are going through.”

Crime + Punishment premiered at the Sundance Film Festival — where it won the US Documentary Special Jury Award for Social Impact Filmmaking — and can be streamed on Hulu. In June 2018, after the film played at Sundance, the NYPD released data on the last three quarters of criminal summonses activity, and it included race data. The report, Maing states, “actually proves the thesis of the film that for some of the top-earning infractions that exist in equal measure in white and minority communities — open container, possession of marijuana, etc. — black and Latino communities are being criminally summonsed more than whites at a rate of roughly 5.6 to 1.” He adds: “This is newsworthy.”

Ultimately, a federal judge dismisses the quota portion of the NYPD 12’s lawsuit against the City of New York. While the outcome is a setback, Maing says, there is still hope to be had in the NYPD 12’s continued mission. “These are people who, if you just met them in an interview, you would bring all the presumptions of what you think cops are. Yet, these are individuals who defy our categorizations of who we believe law enforcement to be. And they’re incredibly well-meaning, caring individuals.”

Since its premiere, Crime + Punishment has received a Best Feature nomination by the International Documentary Association, and Maing — along with the NYPD 12 — will be honored at the 2018 IDA Documentary Awards with the Courage Under Fire Award. The film has also been nominated for Best Documentary Feature by the Critics’ Choice Documentary Awards and is on the DOC NYC 2018 Short List.

As Crime + Punishment reaches a wider audience, Maing can’t help but continue to care for the protection of the subjects in the film. “I wondered for a long time if the Department would embrace the urgent questions raised in the film or just allow ongoing retaliation against the NYPD 12 while refuting their claims. After filming ended, Sergeant Edwin Raymond aced the Lieutenant’s exam and should have been promoted, but instead is now faced with potentially career-ending departmental charges — something he almost prophetically anticipated in the film. So, it’s disappointing to say that [the NYPD] may likely be taking a more aggressive approach. For this reason, my greatest hope is that people remember this is not just a film — Raymond and all of these officers need everyone’s active support and attention.”

But the documentary, Maing stresses, is “not anti-policing or anti-cop in any measure.” He adds: “All of the cops in this film believe deeply in the mission of policing.” The filmmaker emphasizes that the current media landscape has positioned people to belong to one of two allegiances: anti-police or pro–law enforcement. That way of thinking, he underscores, won’t contribute to any constructive conversation about how to rectify the systemic problems of race and policing.

Crime + Punishment, he states, “is all about rejecting that.”