Crash: Driver’s Side

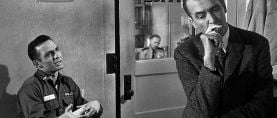

Director David Cronenberg pulls over to answer AC’s questions about his latest film.

obviously pleased with his directorial efforts.

As the director of such uniquely disturbing and thought-provoking films as Rabid, They Came from Within, The Brood, Scanners, Dead Zone, Videodrome, The Fly, Dead Ringers and Naked Lunch, David Cronenberg has displayed a persistent interest in the horrors of the human body and mind. In The Brood, for example, a woman's psychic anxiety produces a horde of murderous mutant children; in The Fly, an overly ambitious scientist finds himself slowly transforming into a winged insect; and in Naked Lunch, author William S. Burroughs' kinky, drug-fueled fantasies are realized with hallucinatory relish.

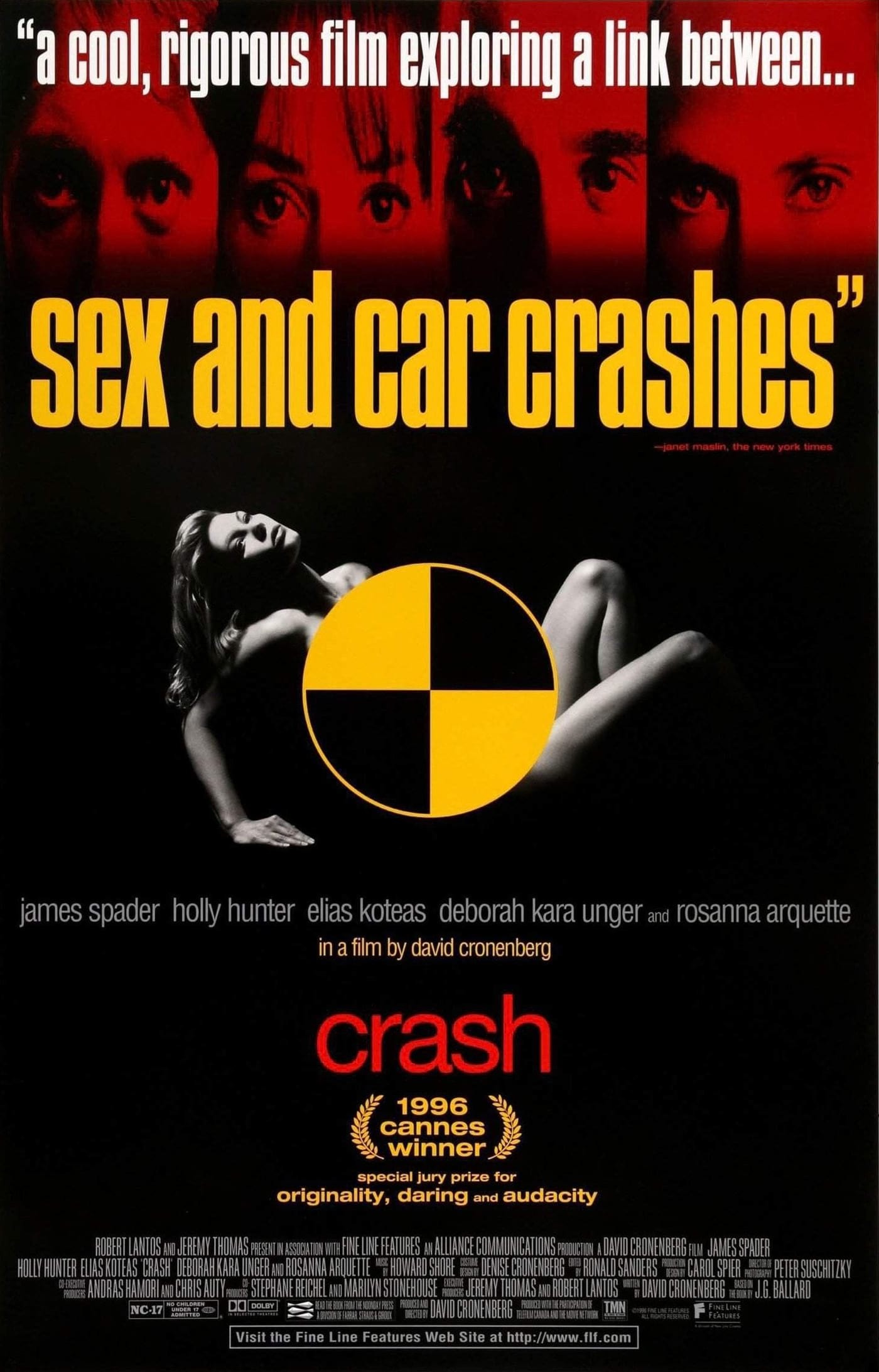

Cronenberg's latest film, Crash, based on the novel by J.G. Ballard, presents a psychological future-scape populated by characters who, having lost the ability to connect on an emotional level, engage in fetishistic sex and bizarre car-crash rituals. Like Naked Lunch, Ballard's tale was almost universally regarded to be unfilmable, but Cronenberg has managed to turn the author's imaginative but decidedly offbeat material into an intriguing and enigmatic motion picture. After winning a Special Jury Prize at the 1995 Cannes Film Festival, the film has caused a firestorm of controversy during its release elsewhere in the world, and its appearance on U.S. screens promises to be no less provocative.

AC editor Stephen Pizzello recently flagged down the Canadian auteur to elicit his views on the Crash phenomenon, as well as details about his collaboration with director of photography Peter Suschitzky.

American Cinematographer: J.G. Ballard's book seems almost tailor-made material for you. Did it immediately strike you as being something you had to film?

Cronenberg: Not at all. The book was sent to me by a lady journalist who thought I should make a movie out of it. I found the book to be very difficult, intense and strange. When I finished it, I thought, 'I can't see why [this journalist] thinks I should make a movie out of this book.' So I didn't have an immediate epiphany about putting the story on film. A couple of years later, just after finishing Naked Lunch, I was talking to [producer] Jeremy Thomas, and he asked me, 'Is there something else that you'd love to do, because we should work together again.' I said, 'Yeah, I think we should do Crash, do you know that book?' Jeremy got very excited, because he had optioned the book when it first came out. He knew Ballard, and wanted to introduce us immediately.

What was it about the story that made you finally want to do the project?

I don't mean to sound evasive, but as is often the case with me, I had to make the movie to find out why I had to make the movie. It was not something that was obvious to me. I think the book started a process in me that was working away under the surface. I had to make the movie to complete the process. If a movie works, it seems obvious in retrospect that it was the right decision to make it. Of course, when I read the book, I could see what I considered to be some superficial connections between the book and my earlier work, but now I see that the connections go very deep.

With both Naked Lunch and Crash, you seem to be making a habit of adapting stories that many people consider to be 'unfilmable.' Did you consciously set out to challenge yourself in that respect?

No. Not much of what I do is conscious. [Laughs.] It is and it isn't, when you come to major decisions like that. I try very hard not to worry about how I'm perceived, or about the arc of my career. It's only in retrospect that it all has some shape. I have to say that for me, all books are unfilmable. I have a very high regard for prose fiction and fine writing. As two distinct media, film and books are completely different. One does not supplant the other; if you really want to do the whole Crash experience, you should see the movie and read the book as well.

The movie has already generated a considerable amount of controversy, particularly in the U.K., and it seems certain to ruffle some feathers here in the States, where politicians regularly demonize 'sex and violence in the movies.'

The difference is that the film will be released after the U.S. elections, whereas the Brits were pre-election. I think that timing has a lot to do with [the controversy surrounding the film] — which is not to say that if the movie appeared in the midst of a desperate time for some political party, they might not grasp it as some sort of solution for a problem they have. There's no question that there's a Puritan strain in U.S. life; it's perhaps less obvious than it is in the U.K. The reaction in the U.K. has been very strange and hysterical. People say to me, 'Well, you must be excited about the publicity,' but the whole thing has nothing to do with my movie anymore. The sad thing is that everyone has heard of the movie, but very few have seen it. And when they finally do go, their expectations will be so deformed by everything they've read that they'll have to see it three times to really see it. I don't think of that as good publicity. More than half the people who were ranting and raving hadn't seen it — even the critics. It's like a phantom of my movie was being attacked, rather than the movie itself.

It seems to boil down to an issue of artistic freedom.

I agree completely. It has to do with our understanding of democracy and freedom of speech. The interesting thing in the U.K. is that during all of the debates, no one has mentioned the word 'freedom.' It's as if it's political suicide to mention that word there now, because freedom is equated with license, and they're totally into control through fear.

Why has it taken so long for the film to be released in the States?

Ted Turner's company bought New Line Cinema, which was supposed to have autonomy. But Turner saw the movie, freaked out, and leaned on the people at Fine Line [the New Line subsidiary that was handling the film] not to release it. They had an argument, basically. The film was supposed to be released on October 4, as it was in Canada, and it wasn't. It was stalled, and then Turner came out in public and admitted that he hated the film and had tried to put the brakes on it. He lost the argument, so now he's just rolling his eyes heavenward and saying, 'It's out of my hands.' I think that's what he really wanted all along — to be able to say, 'I didn't want to release it, so it's not my fault.' He feels that teenagers who see the film are going to do bad things. Teenagers are gonna have sex in cars? I mean, my God, what a revelation! Ted Turner sort of positions himself as a liberal vis a vis Rupert Murdoch, but if he's the liberal champion of the U.S., you guys are in big, big trouble.

[Ed. note: AC's attempts to elicit a response from Mr. Turner were unsuccessful.]

You've collaborated with cinematographer Peter Suschitzky several times now. Why does that relationship click so well?

It's always a mystery when two people click in a collaboration that's as intimate as the one between a director and a cinematographer. It's a matter of temperament and all of the other usual things. I love the European elements of Peter's character, and his approach to filmmaking as a very serious art form. He's not humorless at all, but he does take it seriously. My own approach to filmmaking has basically been split between Hollywood and Europe. Toronto is literally positioned in the middle of those places. I've always been drawn to the more European structures and looks for my films, and that's what Peter has.

How involved do you get with the lighting of your films? How do you and Peter break things down on the set?

We allow each other to talk about anything with each other. He can talk to me about casting, and I can talk to him about where he's putting his flags. I primarily talk to him in terms of the effect that's being achieved, rather than getting technical about how he should or shouldn't do it. We're in the age of really good color monitors, and I think they're a big help in terms of lighting. I think [figuring out how things will look in the finished film] still requires interpretation, but [the monitor images] are getting closer and closer to looking the way things really will look on the screen. We can look at a frame and talk about what's going on in it and what the light's doing.

The book takes place in London of the future, but you set the film in Toronto. Did you feel that the new location fit the mood of the story? How did you try to maximize the city's futuristic qualities? Crash reminded me a bit of the look that Godard created for Alphaville, in which 1960s Paris was lit and shot so that it appeared to be futuristic.

There are a few levels of things that I can discuss in response to that question. First of all, although Ballard's book is set in London technically, and he uses English names for a lot of the roadways and overpasses, the setting felt like North America to me when I read the story. The cars in the book weren't Morris Oxfords, they were '58 Buicks. When I told Ballard my take on that, he completely agreed with me. He has a yearning for America, especially when it comes to a car like a '63 Lincoln. A '63 Lincoln on an English road is a strange anomaly. It's not at home there, but it is in Toronto. The car is iconic, symbolic and metaphorical in the film, but not in the same way [as in the book]; a guy riding a Harley through the streets of London is a statement of a particular kind, but it's quite different if he's riding it through the streets of L.A. I felt that the book was always spiritually set in North America, and so did Ballard. In a way, by the time I was ready to make the movie, that had already been unconsciously decided on my part; New York is a special case, and so is L.A., so what do you do, go to Chicago? Toronto was the perfect place.

The visuals in this film seem a bit less elaborate and more low-key than the wild images of some of your previous films.

I think it is a very elaborate scheme, but it's invisible. The logistics were actually quite complex, because we wanted a very controlled look. We were shooting outside, and we didn't have the budget to light five miles of road, so we had to integrate the available light. Some of the locations were chosen for the type of light we would be dealing with. We had to combine what was available with the elements we could control in the foreground. Often we were carrying lights on a trailer towing a car, and the lighting would just precede the frame. So it looked as if we'd lit lots of road, but we were really only lighting the section we were on, as we moved.

Peter told us that his biggest challenge was shooting the car-to-car footage. What was the toughest aspect of those scenes for you?

Oh, everything. It's the detail that you ignore that kills you finally. You have to try to subdue every obstacle. Getting the roads was crucial. I was watching some movie on TV the other day and I said to myself, 'Uh oh, we're on a deserted stretch of unfinished highway, there's a car crash coming up.' I could just sense it coming. To avoid that predictability, I really wanted the roads in Crash to feel lived-in. We were offered the use of a highway that was under construction, which would have made things very convenient, but it had that same boring feel, so I said no. We actually got the use of roads in Toronto that no one's ever shot on; we shut down some major internal freeways. Part of the reason we were able to do that was my relationship with the city over the years, and part of it was that they were very excited that we were shooting the city as Toronto, and wouldn't be changing all of the street signs to make it look like Chicago. It was a matter of civic pride! It's a wonderful playground to have those kinds of roads at your disposal. But it also created a paradoxical situation in which Peter and I had to shoot action scenes without making an action movie. I had to keep telling the stunt guys, 'No, tone it down, I don't want the triple-flip and the explosion.' We did no slow-motion shooting; everything was done at 24 frames, and it was a very deliberate choice. Two of the most photographed things in movie history are sex and cars. For reasons of both personal ego and cinematic tone, I wanted to shoot those things in a way that no one had ever seen, but not in a spectacular way. This required us to make many small aesthetic choices, such as mounting the cameras on the cars just off the normal axis, or splitting the frame with the guy driving the car on the left and the roadway on the right. It's folly to think that you're going to find an angle that no one has used before. You have to rely on an accumulation of small details to create the feeling in viewers that they've never seen cars shot in quite the same way. Every day we made a little prayer to the gods of cinema that we could find a subtly different way to do everything.

The film has a lot of intriguing symbolism. In the carwash scene where Vaughan is groping Ballard's wife in the back seat of the Lincoln, the heavy strips of material cleaning the car almost seem like extensions of Vaughan's fingers.

That's a lovely perception, because when people talk to me about technology and what it's doing to us, I always reply, 'What are you talking about? Technology is us.' Technology doesn't come from outer space; it's an extension of us, almost an incarnation of human will.

Those scenes lend the film an interesting subtext. Did you plan to use symbolic visuals all along, or did those ideas occur to you later?

It's an organic process. When you're directing a movie, you're making literally thousands of decisions a day, and your orientation to the material is guiding you. It's partly intuitive, because you're usually shooting out of sequence and you're working with actors and lots of other contributors. You're being guided on many levels by many things, and if it all works, at the end it's all integrated and it works in the movie. It's not a process where you make a list of 'stuff' — you know, 'Here's a list of metaphysical stuff, here's a list of symbolic stuff, here's a list of filmic stuff.' It's a constant process of integrating all of these things. For example, we decided to use bruise colors for the costumes. As soon as we made that decision, it affected everything, including the upholstery in the wife's Miata, which is a purply color. We had the car reupholstered just for that reason. In the book, her car is white, but no cinematographer's going to want you to have a white car, so we made the car silver. We had to paint a combination for the car that didn't really exist in the Miata line. So part of the lighting and set decorating was done with the clothes colors in mind. That became a conscious decision, and it gave us an orientation on many levels. Physically, these were the right colors for a story as dark and moody as this, and symbolically, they worked for the characters, who are very bruised people trying to recover some kind of life. The point you made about the futuristic look is very interesting, because there's nothing in the book that's futuristic, even though lots of people think of Crash as a sci-fi book. When you read it, it's very hard to justify the 'sci-fi' label in the usual way. But in my opinion — and I felt it was the boldest part of the book — I think the psychology of the characters is futuristic. It's as though Ballard has anticipated a kind of common psychopathology that may no longer look like one because everyone will have it. It will be the normality. He did that in the book, and I did it even more rigorously in the film. Ballard and I were at a press conference overseas, and a Finnish journalist said, 'I really liked the movie, but I don't think the movie goes as far as the book.' But Ballard very graciously replied, 'I completely disagree, I think the movie goes much farther than the book, and I think the movie starts where the book left off.' That sort of ended that discussion. I had to go through a distilling process when I was writing the script. I wanted to begin with that psychology, and I did my own version of the jump-cutting that Godard pioneered in Breathless, excising all of the things that didn't interest me. I didn't want to show viewers how these people got that way, or why they got that way. What interested me was, 'Where do they go from here?' The book has that inner monologue that you can never do on film, and it's the thing I'm most jealous about when I think of writing. Voice-over can sometimes work, but it's quite a different thing. So the sci-fi aspects of the book is more of a tone that comes from the characters and their weird disconnections dialogue and relationships. Peter and I were looking for a visual correlative for that.

The film's atmosphere of alienation is heightened by the unreality of the staging. There are very few people around except for the main characters.

I had a very enthusiastic A.D. who was always ready to fill up the streets with a hundred extras at any moment. I didn't want any of those people in the frame, because I wasn't interested in them. The result is a sort of isolated, abstracted feel that reflects the internal world of the characters.

The sexual positions of the characters in the story also reflect that alienation and distance. The characters are physically uninhibited, but at the same time emotionally repressed.

Right, it's always as if they're looking off into the distance at a third person, or at their own future, rather than at each other. As you've pointed out, that's another way of being repressed — to be able to do anything physically, but nothing emotionally. The sex becomes an out-of-body experience; it's almost as if these people are trying to reinvent sex because the old forms aren't working.

Did the graphic nature of the sex scenes make them particularly difficult to film?

Not really. They were tough only because everything is very fussy in a sex scene. I don't mean that the actors are fussy; it's just the angles and the aesthetics of it. I often found myself arranging Debra Unger's hair on the pillow just for the sake of continuity. The positions of bed-cloths and hair are absolutely unrepeatable; there's no way you can get in and out of bed and have those two things stay the same. That was difficult and agonizing. A lot of that footage looks as if it was done in one or two takes with multiple cameras, but I never use multiple cameras unless I'm doing an action sequence that can't be repeated. Almost all of the sex scenes involved multiple takes. The carwash scene, for example, took three separate days. We were shooting with a car that had been cut in half, and the front seat was different than the back seat. Likewise, the shot of the two guys kissing was done over three days; part of it was done on a set, part was done outside, and part was done on another set. Naturally, shooting that scene involved a lot of intensity and humor. You can't drag actors kicking and screaming into roles like these; they have to be gung-ho and excited to do it. The sex was almost not discussed, because it was all there in the script. I did use a very good color monitor so that I could tape everything and show it to the actors. It wasn't a normal procedure, but I wanted to extend them that courtesy so that they would feel comfortable. I wound up doing that for other scenes that didn't involve sex because I didn't want them to have any surprises during the dailies.

The camera lingers over car-crash wounds throughout the film, and almost eroticizes them.

In Dead Ringers, the character of Elliot says, 'There should be a beauty contest for the inside of the body.' As human beings, our sense of what's beautiful or repulsive is only skin deep, even when it comes to our own bodies. I'm always interested in taking something which seems repulsive at the beginning of the film and making it appear beautiful and inevitable by the end. I can't achieve that with every viewer, but with some people I succeed. The book of Crash is not written like porn at all; it's very clinical and very medical in its descriptions of everything, including sex. But at some point you find yourself being turned on by it, and you say to yourself, 'Oh my God, I'm capable of being turned on by this? It's unbelievable.' I would love to have that happen with the movie.

There is quite a bit of sexual tension in the scenes involving Rosanna Arquette's character. The deep scars on her legs become an erotic focal point.

At those points, you are hopefully entering into the psychology of the characters. I'd like people to be thinking, 'Even though I would have thought that these feelings were completely distant and impossible for me, I do have a kinship with these characters.' As soon as you've made one connection like that, you can start to make others.

Do you believe, as Ballard does, that our interaction with technology will result in some sort of physical evolution?

I think the technology is only incidental. As I said earlier, I feel that it's just an extension of human will. We seized control of our own evolution many years ago, and we're probably the only creatures in the universe who have ever done that. It's no longer the survival of the fittest, because what constitutes the fittest? Is it the guy who makes a lot of money and can buy a Mercedes, get the most babes and reproduce his genes the most often? It no longer has to be the guy who's physically the strongest and most aggressive. I think, more likely, that a completely different dynamic of evolution has set in that we're not completely aware of. We are willing ourselves to change, just as we always have. We don't accept the world as a given; we build houses, we change the temperature to suit ourselves, and we don't accept that you can't have light once the sun goes down. We also don't accept when we're sick, crippled or depressed. Prozac is now part of our evolution; we've externalized our bodies' chemistry. That's the nature of the human beast, and the movie does touch on that.

Contrary to what some people have said about the movie, it seems as if there's an underlying thread of optimism in the story.

Personally, I don't think that the movie is depressing at all. The characters don't just cave into the empty, lifeless situation that they find themselves in. They seek life, even if they're seeking it through death or danger. And I think that's very human. The melodrama and extreme situations in the movie hopefully will serve to highlight those feelings and show how they can apply to more mundane situations in real life.

Cinematographer Peter Suschitzky later became a member of the ASC, and subsequently collaborated with Cronenberg on the films eXistenZ, Spider, A History of Violence, Eastern Promises, A Dangerous Method, Cosmopolis and Maps to the Stars. You'll find a complete interview with him about the making of Crash here.

For access to all 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.