Working Remotely: Cinematography Across Continents

Markus Förderer, ASC, BVK discusses his experience with “remote” shooting to ensure health and safety for cast and crew.

Photos by BerghausWoebke Filmproduktion/Tobias Bloier

In the current climate of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the world cautiously peeks their heads out of quarantine to start slowly “opening up” and some countries have allowed production to resume under strict health and safety regulations. Germany is one such country who has allowed work on film and television to resume with restrictions. This was moderately good news for cinematographer Markus Förderer, ASC, BVK as the feature film Haven: Above Sky, which he shot in 2018, was headed for additional photography.

“It was only a week before that Germany had officially made it possible to have film shoots again with special safety protocols,” explains Förderer. “A safety and health person was on set the full time, screening temperature, and checking for symptoms on all cast and crew. Extras received rapid COVID tests in the morning and were not allowed to work until the results were returned. It was a skeleton crew and, of course, everyone had to wear FFP2 masks [the European equivalent to N95] and follow heightened cleaning and safety protocols.”

In the middle of May, even though some countries were relaxing quarantine orders, travel was exceedingly difficult and Förderer’s flights were continually canceled to make the trip from his home in Los Angeles to the stages in Munich, Germany. It became clear to the cinematographer that there was no guarantee he could make it to the reshoots. Förderer has a strong relationship with the director, Tim Fehlbaum, as they had previously worked together on the director’s first feature film, Hell, in 2011, and the two began discussing options for the cinematographer to participate in the reshoots virtually via a video conferencing application.

The cinematographer had some concerns about not having a more active hand and control over the reshoots which involved shooting miniatures, front projection, smoke, CO2 effects and interactive lighting emulating a spacecraft re-entry. “The lighting had to match and intercut seamlessly with footage from principal photography” notes Förderer. “Working with miniatures is wonderful, but it’s also a bit tricky and can look cheesy if you’re not careful. Our main camera was a Red Monstro with large-format sensor and we also used a Helium, with a smaller Super 35-size sensor to get a little more depth of field without having to stop down. Matching lighting was going to be a little tricky, as we had a lot of water effects and fog and I was shooting with Hawk 65 Vintage lenses that have very low contrast. All these variables can make it fragile to match with certain shots. It was all planned out and I was nervous about not being there to execute it.”

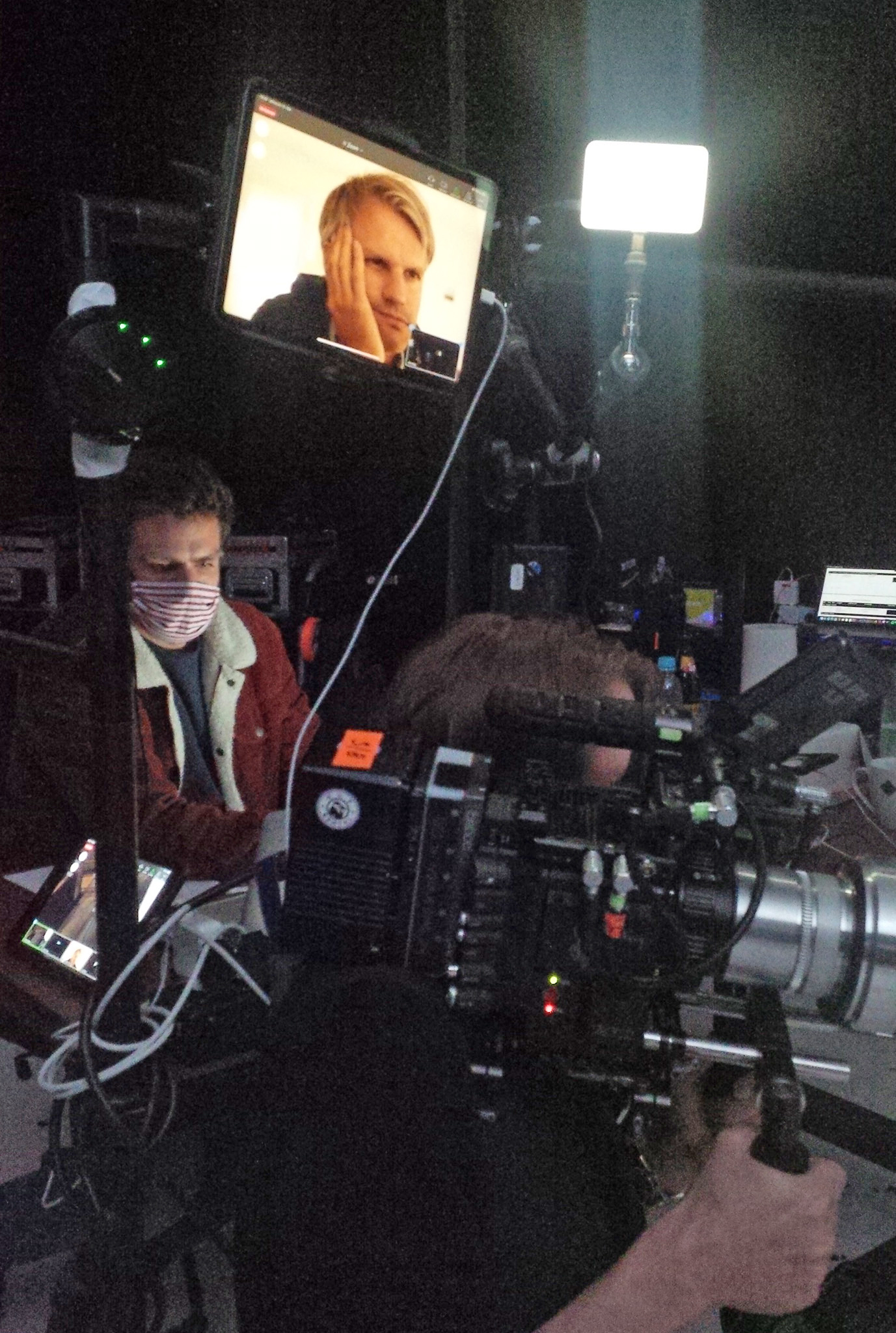

A few days prior to the reshoots, it was looking even more dire for Förderer to be able to make the trip. This author conducted an interview with the cinematographer during quarantine for an upcoming ASC online video series. In order to avoid the ubiquitous – and often lacking – webcam visual quality, we elected to deliver sterilized equipment to each interviewee to set up on their own and shoot their side of the interview discussion. This included a Blackmagic Design Pocket Cinema Camera 4K with a Fujinon MK 18-55mm zoom and a Blackmagic Design Web Presenter. The Presenter allows the Black Magic camera to connect via USB to a computer and the software “sees” it as just another integrated webcam to incorporate seamlessly with most of the video conferencing applications in use today. In this case, we connected via Zoom app to talk and, in addition to the cameras connecting through the application, we each locally recorded our own images to avoid any compression artifacts induced by the online connection. Förderer was so impressed with the ease of the communication and quality of the image that he asked if he could hold on to the setup for a couple days, which we gladly accommodated. He then convinced the producers in Munich to acquire a similar setup and it became increasingly clear to both him and the production that his virtual presence could be significantly more than just virtually “visiting” the set and consulting, but rather he could embody his full role as cinematographer and direct the photography from another continent.

“In the beginning, the discussion was, ‘Well, you can help consult…’ because no one knew if my attending the shoot virtually would work or not,” recalls Förderer. “But the closer that we got to the shoot, and we tested the idea of connecting via Zoom, it started to look like I could actually become more involved than just consulting. Seeing the quality of image that could come across Zoom with the Blackmagic Presenter, I became convinced that I would be able to actually make some legitimate visual assessments of the production and image from the cameras completely virtually.”

To assist the virtual side of things, the production hired Clemens Krüeger, a young cinematographer, who was integral in prepping and setting up locally on the soundstage, as well as the show’s gaffer, Uwe Greiner, who worked on the main shoot with Forderer. In addition to the iPads, Förderer communicated directly with Greiner via WhatsApp to give him notes as the days went on.

“It really worked quite well,” attests the cinematographer in a phone conversation after the fact. “The production connected several iPads on the stage to the Zoom call, along with a feed directly from the production cameras via a Blackmagic UltraStudio SDI box and an iPad at the director’s monitor so that I could see multiple viewpoints, communicate with the director and with my gaffer and local DP as well as see the image being recorded by the camera. We were shooting with two cameras, a Red Monstro and a Red Helium and we made sure to send the monitor tools overlay to the Zoom feed so that I could see the camera settings and histogram and judge exposure.”

Even with the quality of the image from the Blackmagic hardware and Zoom conferencing, there were still compression issues to deal with. To combat this, producer Philipp Trauer — who also took a page from his former experience as a DIT — would take full-resolution still outputs from the cameras and email them to Förderer so he could better judge the image quality for subtleties including shadow detail and noise.

Due to the time difference, while the production was working three normal days in Munich, it was three nights for Förderer in Los Angeles, who sat by his computer and supervised the entire shoot. “I first thought that maybe I would be there for the first hour of the shoot and then go to sleep, but it was all working so well that I stayed through the whole thing. A real credit to Clemens, as well, this could not have been easy for him to be following the lead of a guy on a monitor overruling and changing stuff all day long.”

“There were a lot of benefits to this kind of working,” Förderer continues. “There’s no jet lag to contend with when you arrive and then have to go to work immediately. There’s no time lost to traveling, either. There are many times where reshoots come up and you can’t do them because you’re on another show or some other schedule conflict comes up, and this kind of working allows you to still do the job. Working nights is never easy, but here we could wrap and I could literally walk one room over and go to bed. That was pretty amazing. The overall feeling of the day was not a lot different from what I normally do; it was a lot like working with an operator where you’re mostly sitting by the director at the monitor. The crew would have to move around a couple of the iPads for me and every once in a while, the wifi on the stage would drop out, but overall, it really worked incredibly well. For the director, it’s incredibly important to have their cinematographer with them the entire time. This makes sure that the whole film feels like one piece in the visual language and this way we could make sure that happened.”

The distance shooting went both ways, too. As some five or six additional closeups needed to be shot with a key actor — who was also in Los Angeles and couldn’t get a flight to Munich — Förderer set up a no-frills shoot in his own home in L.A. “I bought a smoke machine off Amazon and set up the couple of shots in my living room and filled in the holes, while director Tim Fehlbaum was on the other end on Zoom. Of course, this kind of thing couldn’t happen without the director’s full support and faith. But the shots worked great and they cut in seamlessly.

“The big takeaway for me here is that when I can’t be there, or when it makes sense — just one additional day of photography or something — this kind of remote shooting works,” concludes Förderer. “This is especially helpful if you already have a good shorthand with the director and gaffer. I hope that other productions take note on this, not just because of COVID, but even after – this kind of thing works. Even as we’re starting to open up again and there’s concerns about how many people can be on set, perhaps the DP and script supervisor and producers can all participate virtually in some cases and limit the people who have to gather together. Sometimes there was a challenge to communicate exactly what to do with a complicated reflection or something when being there I could have quickly solved it, but for the most part it was an amazing experience. I also hope that camera manufacturers take note. While Canon and Sigma are already building webcam functionality into some of their cameras, it would be amazing to also have this function in professional [production] cameras so that they can be easily connected for virtual viewing. There are a lot of potential in helping to streamline our return to normal production and to accommodate situations where the DP just can’t be there for a day or two. Maybe, for these kinds of shoots, this is the future.”