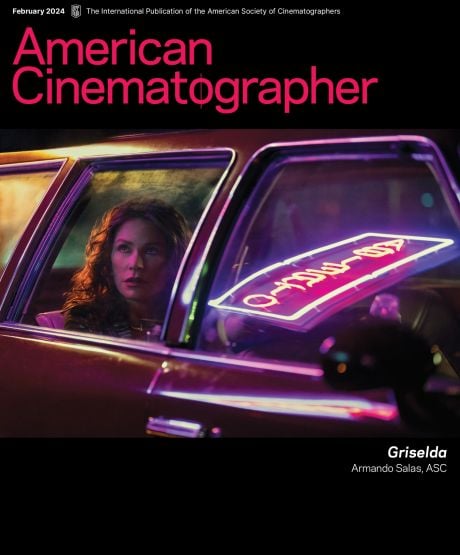

Cinematic Glory: Freddie Francis, BSC

The legendary English cinematographer/director discussed his exceptional career as the ASC honored him with its International Award in 1998.

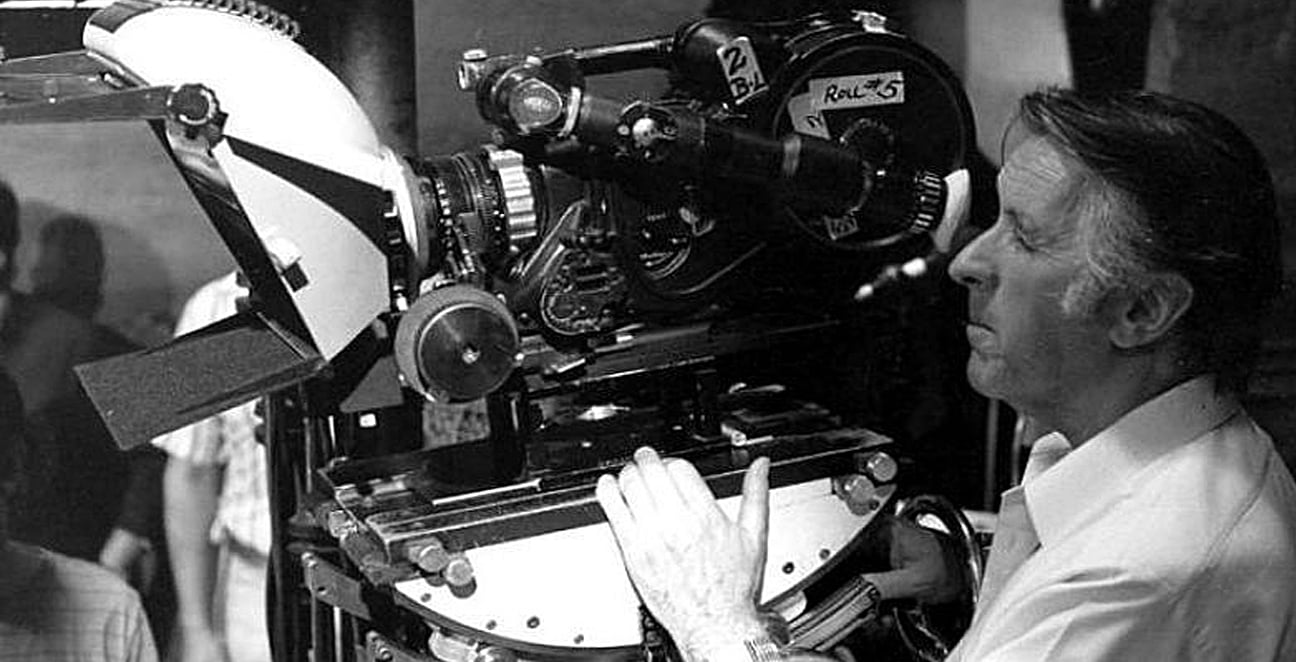

One hallmark of a dedicated artist and true professional is the willingness to accept new challenges — an attribute that cinematographer/director Freddie Francis has exhibited throughout his continuing lifetime of work behind the camera. Indeed, his credits as a director of photography include such disparate films as Time Without Pity, Room at the Top, Sons and Lovers (which earned him the Academy and BSC Awards for Best Cinematography), The Innocents, The Elephant Man (which garnered Francis another BSC Award and a BAFTA nomination), The Executioner’s Song, The French Lieutenant’s Woman (BSC Award, BAFTA nomination) Glory (Academy and BSC Awards, BAFTA nomination), The Man in the Moon and the hair-raising 1991 remake of Cape Fear (another BAFTA nomination). Ever the experimenter, Francis recently completed a feature film shot in the Sony high-definition digital video format.

In recognition of Francis’ outstanding contributions to cinema history, the American Society of Cinematographers will present him with its International Award at the organization’s 12th annual awards gala, to be held on March 8 at the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles.

Previous recipients of the honor are Gabriel Figueroa, Henri Alekan, Raoul Coutard and Francis’ longtime friends and fellow BSC members Freddie Young and Jack Cardiff.

During the past year, Francis was additionally honored by the members of the British Society of Cinematographers, who saluted their esteemed peer with a Lifetime Achievement Award (announced by Sir Sydney Samuelson and presented by Oswald Morris, BSC).

“To get this award from [the ASC] is an absolute highlight in my career. In a way, it brings me closer to those who inspired me.”

— Freddie Francis, BSC

Several months ago, this reporter was warmly welcomed by Freddie and Pamela Francis at the couple’s stylish home, located just outside of London. The cinematographer smiled as he described his feelings about being the sixth recipient of the ASC’s International Award. “It was [then ASC president] Owen Roizman who called to tell me about it, and I was absolutely thrilled,” he said. “As a kid, I wanted nothing more than to be a part of the film business. I really looked up to the many talented members of the ASC, such as Gregg Toland. Over the years, I’ve visited the ASC several times and met many of the people I’d admired; to get this award from them is an absolute highlight in my career. In a way, it brings me closer to those who inspired me.”

Roizman, a co-chairman of this year’s ASC Awards committee, comments, “I think Freddie Francis is a perfect choice for the honor not only because of the diverse work he has done in both England and the United States, but because he is still a vital member of our profession. That says something about his artistry and his dedication to the craft of cinematography.”

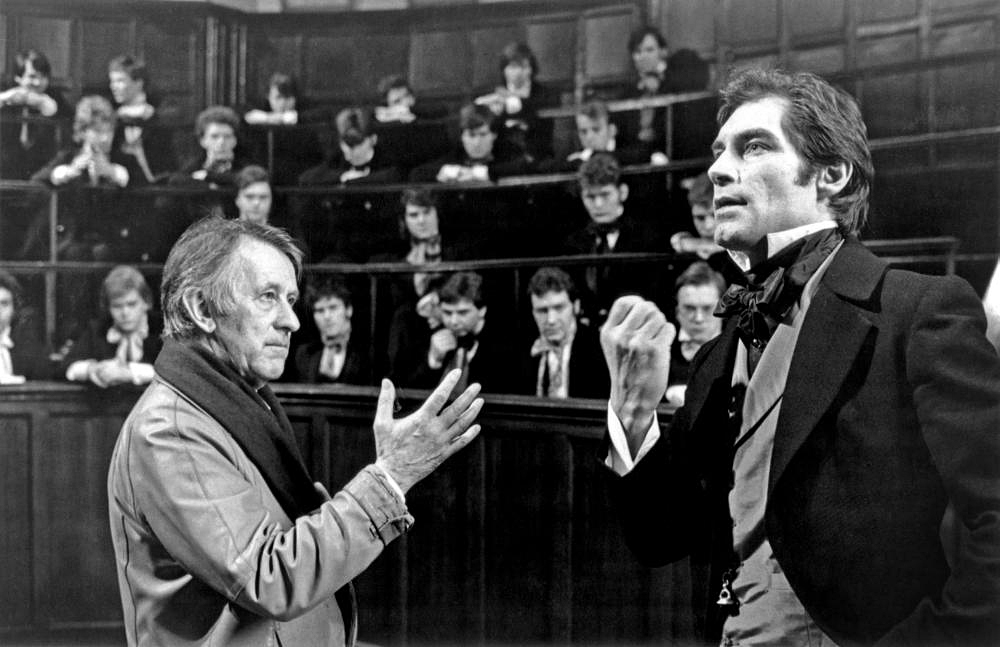

Committee member John Bailey, ASC recalls, “When I started film school at USC in the mid- Sixties, there were two kinds of films that most of us went to see: the art-driven films made by people like Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni, and the guilty-pleasure films, which included Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns and — for me — the Hammer Studios horror films, a number of which were directed by Freddie Francis. He’d become a director at that point in his career, and he made quite a number of those films in a very short period of time for Hammer and a few other English studios. I remember how exciting and wonderful they were; while they had their B-movie roots, they were incredibly rich in their imagery, expressive, and fun to watch. They were often shot in Techniscope — a spherical, deep-focus widescreen process similar to Super 35 — and I recall how those pictures were as important to me as the films made by Antonioni, Bergman and Francois Truffaut.

“I’m very pleased that Freddie Francis is being given the ASC International Award for his considerable body of work as both a cinematographer and a director who had a very strong influence on a generation of American filmmakers — the film school brats of the 1960s!”

When asked how his long career began, Francis wryly responds, “As a young man, I was in love with actress Joan Blondell! Of course, she double-crossed me and married a cinematographer, George Barnes [ASC]. So I absolutely had to become a cameraman!”

Kidding aside, Francis notes that he had dabbled with still photography in his youth, but actually thought of becoming an engineer. “I had this romantic notion of building bridges across great rivers in remote countries, but in those days, the schools would have had in me in training to work in an ironmonger’s shop,” he recalls. Francis was later assigned to write an essay on a personal interest. Fascinated by movies, he selected filmmaking as his subject and visited Gaumont British Studios for research purposes. “Apart from Joan Blondell, I got hooked on the whole thing right then and decided that filmmaking was what I really wanted to do,” he says.

After briefly apprenticing for a still photographer, Francis found work as a clapper boy at British and Dominion Studios, which primarily made “quota quickies” — low-budget productions financed by Paramount Pictures so that the American studio could gain access to the lucrative British market for their Hollywood-made films. He explains, “Paramount would spend as little money as possible on these horrible pictures, which we made on a 10- or 12-day schedule. Films were just a way to make money or find a job for your girlfriend, and then they were never shown anywhere other than the Plaza Theater in London, which was owned by Paramount! I think they were even screened in the morning when the theater was being cleaned — Paramount was just fulfilling their obligation.

“This might sound very anti-British, but filmmaking here was a joke in 1933 when I started out! Aside from Freddie Young and Alfred Hitchcock, there were very few people to learn from and emulate. But I was observant, so if I learned anything about cinematography by working on these films, it was all from others’ so-called mistakes! Regardless, it was good experience. A lot of good people came through those channels. In a way, our education was financed by the Americans.”

Later, while working at Pinewood, Francis became a loader, a focus-puller, and then an operator for a short time before World War II engulfed England. Drafted into the army, he discovered that there was a stills and photographic unit. “They had a lot of equipment, but nobody knew how to use it,” he remembers. “I got in there to become a one-man film unit for a while, making training films. Those in command later decided that movies could be used to boost morale, and established a professional film unit, the Army Kinematograph Services. Carol Reed, Thord Dickinson, Freddie Young and a lot of people of that standing were in it, and I joined them as well.” Francis’ wartime pictures included Maxillo Facial Surgery, which detailed how front-line army doctors dealt with disfiguring wounds, and training films for antiaircraft personnel — shot with infrared stock during actual air raids.

During the war, British film entered a renaissance period, as filmmakers such as David Lean, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressberger and others came to the fore. “The industry was in much better shape,” Francis recounts, “and just two weeks after I was discharged in 1946,1 was on my way to East Africa to do location work on The Macomber Affair, an American picture directed by Zoltan Korda and starring Gregory Peck and Joan Bennett.”

Soon after, Korda took over British Lion Studios and Francis was placed under contract as a camera operator. He later operated for Christopher Challis, BSC on a several productions for director Michael Powell, including The Small Back Room and Tales of Hoffmann, and for Oswald Morris on such films as Moulin Rouge and Beat the Devil, directed by John Huston. “I got along very well with John, and he gave me a very free hand as an operator,” Francis says. “We did seven pictures together, but in 1955 I finally told him I had to start shooting on my own, so he brought me in as the second-unit cameraman on Moby Dick to shoot all of the miniatures and the whaling footage. After that, I was recommended to a couple of producers, and I did A Hill in Korea [1956], my first film as a director of photography.”

After such successful “kitchen sink dramas” as Room At the Top and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, Francis’ work began gaining notice, resulting in his next project. Based on D.H. Lawrence’s autobiographical novel and directed by famed cinematographer Jack Cardiff, BSC, Sons and Lovers (1960) depicts societal repression in a small coal-mining town during the early 1900s, focusing on an artistically gifted young man (Dean Stockwell) whose romance with a young farm girl could doom him to a life in the mines.

While Cardiff earned an Oscar nomination for his efforts, Francis’ CinemaScope camerawork bested the other nominees in the Best Black-and-White Cinematography category. As noted in the May 1961 issue of AC, the picture has “unusual visual beauty and is marked by photographic ingenuity throughout that easily makes it one of the finest monochrome photographic achievements to come along in some time.”

Admirer John Bailey attests, “When I was just starting to become aware of the visual aspects of filmmaking — through such films as La Dolce Vita and Wild Strawberries — I actually thought that artful films had to be made in a foreign language. Then I saw Sons and Lovers, and I was knocked out by the poetry and visual beauty of the film. The camerawork was unlike anything I had seen before in an English-language movie.”

The picture’s widescreen frame effectively adds a momentous sweep to the landscapes surrounding the intimate drama. Perhaps taking cues from Gregg Toland’s work on Citizen Kane, Francis deftly used deep-focus techniques with complex compositions to suggest the characters’ shifting relationships and emotions — a feat made even more difficult by the day’s slow anamorphic lenses. The results were only possible though the use of Kodak’s fast Tri-X stock.

Asked if he’d had any trepidation about shooting a picture for a distinguished cinematographer such as Cardiff, Francis offers, “I had nothing to fear, because Jack had never shot a black-and-white movie! He’d been an operator for many, many years, but he came to prominence though his work in Technicolor. And to his everlasting credit, I never had any interference from Jack on that film. He asked me to shoot the picture because he’d liked my camerawork on Room at the Top, so he knew I was up to the job.”

Francis’ subsequent production was The Innocents, based on author Henry James’ thriller The Turn of the Screw. “That is one picture I’m still very happy with,” the cinematographer says. “The director, Jack Clayton, was a very dear friend, and we had to overcome many technical hurdles during the project.”

The film was made for 20th Century Fox, and the use of their proprietary CinemaScope process was mandatory. Francis recalls, “We only found out about that a few weeks before shooting started, following months of talking about how we were going to make the picture.” The cinematographer found the 2.35:1 aspect ratio to be inappropriate, as the supernatural-themed story demanded a sense of entrapment. To help remedy the situation, he utilized graduated color filters (effectively used as neutral-density grads in monochrome) on both sides of the frame, which could be brought in and out during shots to concentrate viewers’ attention on the center of the picture.

In addition, “CinemaScope lenses also couldn’t focus very close, but Jack wanted the camera to be in tight with the actors. We had to use a lot of light to build up the stop and increase the depth of field. We had a huge garden set built on the stage at Shepperton Studios, and we couldn’t get nearly enough light on it for the stops we wanted, so I had the art department paint one side of the foliage silver and white to create a false highlight. That way, our fill could be what our key would have been. We had to do all kinds of tricks like that.”

Soon after shooting the Hammer Studios production Never Take Sweets from a Stranger, Francis took stock of his career as a cinematographer. “There was a financial consideration there,” he admits with a smile. “Cinematographers working in England didn’t make a lot of money. Even after I won the first Academy Award, my fee wasn’t that much, relatively speaking. You had to keep working all the time, and if you weren’t careful, you’d end up working on films you didn’t really want to do. After Sons and Lovers, people asked me if I wanted to direct, so I thought I’d try it. But my first film was a bit of a disaster.”

Francis’ directorial debut was the 1961 romantic comedy Two and Two Make Six. “I’d been promised that I could change the script, but it didn’t come off that way,” he explains with a wry grin. “At the time, directors had to be approved by the National Film Finance Corporation, which put up the money for production. They’d approved me because of my reputation as a cameraman, but I knew that I’d never get another chance if I backed out of the picture.”

The film was a box-office disappointment, but Francis’ second feature, a thriller entitled Vengeance, was a success. He followed it by directing over 20 features in fewer than 20 years, primarily working for Hammer, Amicus and other British studios specializing in the horror genre. Richly atmospheric, a number of these modestly budgeted films are now considered classics of their kind: The Evil of Frankenstein (1964) features the seemingly undefeatable scientist vowing to continue his experiments; the anthology film Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965) offers five separate stories featuring a werewolf, a vampire, a man-eating plant, voodoo and an a disembodied hand; Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968) trails the infamous Count as he plots revenge.

Francis additionally helmed several features for Tyburn, an independent studio formed by his son Kevin. Not surprisingly, these and Francis’ many other genre credits earned him great admiration from horror fans, which still invite him to speak at conventions and revival screenings. He candidly remarks, “I enjoyed working at Hammer and the other studios, and I kept making one film after another just because I was having great fun — I didn’t realize that they weren’t very good films. Oddly, though, while I have some rather good credits as a cinematographer, I get more recognition than you can imagine for all of those ghastly horror movies!”

Asked how his experiences as a director reshaped his ideas about cinematography, Francis replies, “I won’t work with a director unless I feel that I’m on his wavelength. The three or four weeks I need in preparation for a picture mainly consists of just talking to the director so I can understand what he wants. A director sometimes needs help. I’ve made wonderful films with directors who have never been in a film studio in their lives — they don’t have to know everything. But others, like Robert Mulligan, with whom I worked on Clara’s Heart and The Man in the Moon, are very knowledgeable and organized.

“The cinematographer is an executive of the production and has to run things for the director,” he adds. “You also have to read his mind and then get that up on the screen, because any good director has already shot the picture in his head and can see those images. They can be improved, but they are there.”

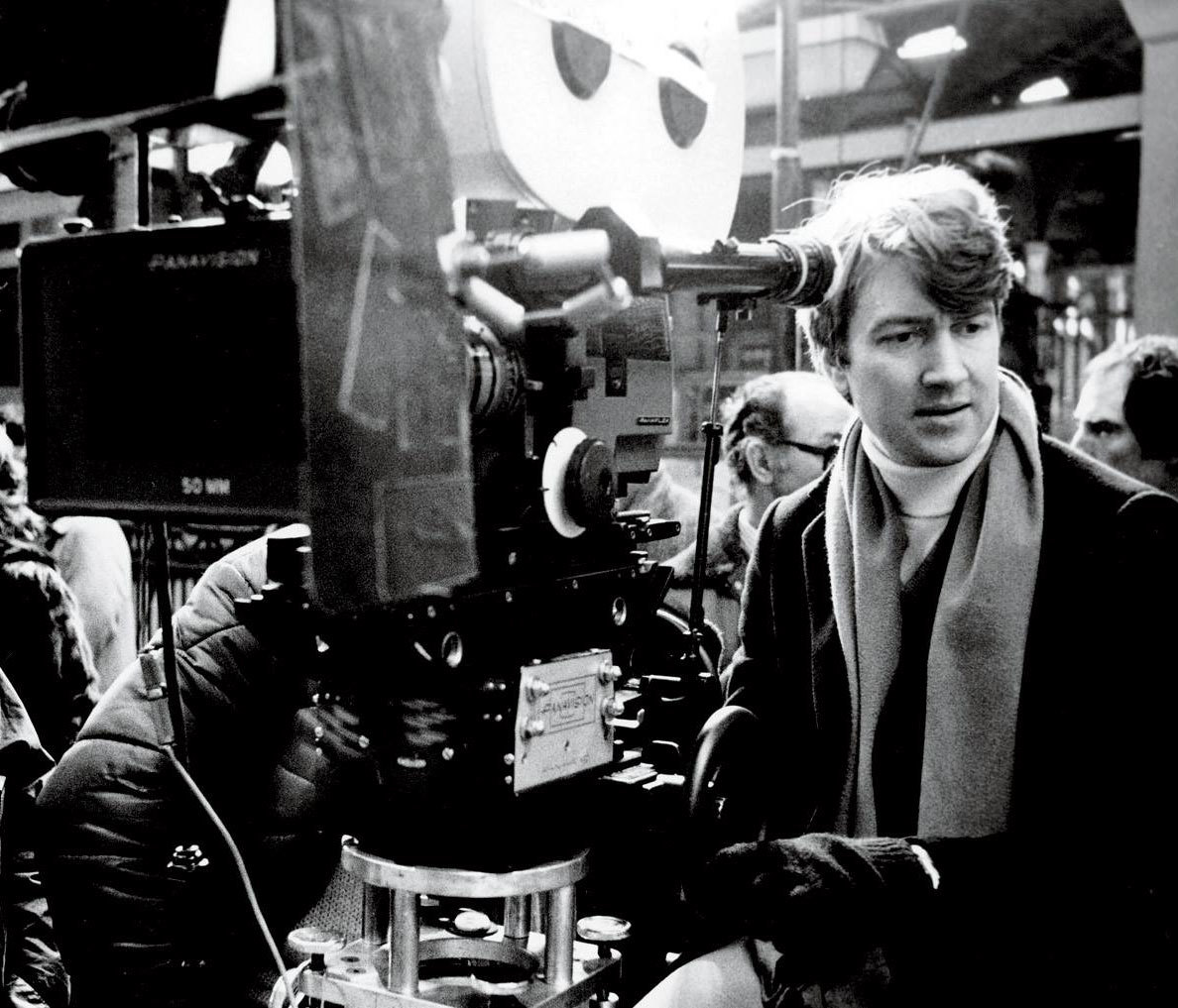

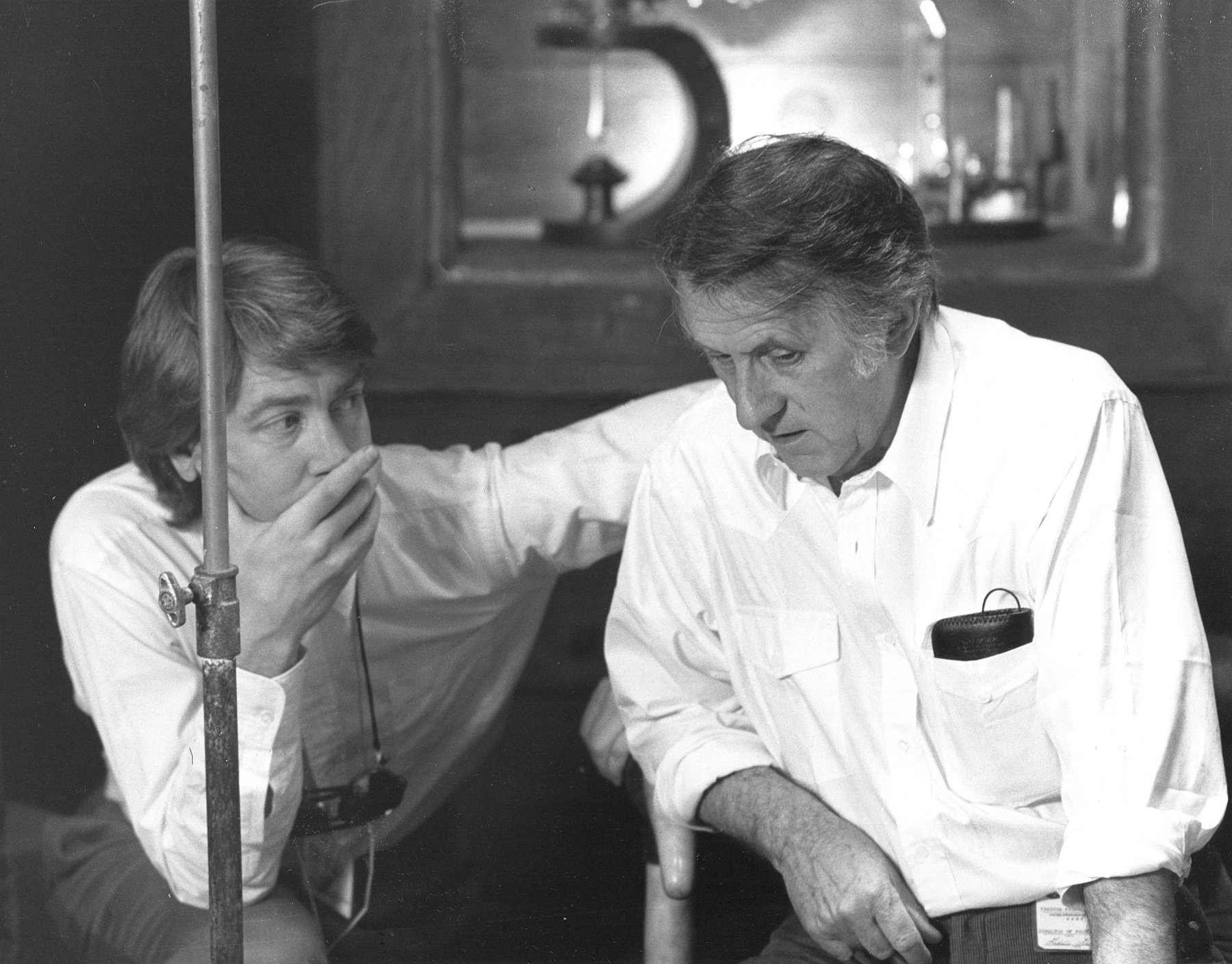

Francis’ next major project would be a perfect example of this dynamic. In the mid-1970s, he took a creative sabbatical to concentrate on writing and developing new material, while also directing some television productions. But, in 1979, he was enticed back into the realm of cinematography by director David Lynch and producer Jonathan Sanger.

Lynch had recently gained attention with his singularly unique film Eraserhead. Impressed with the director’s talents, satirist and horror aficionado Mel Brooks signed on to executive-produce Lynch’s next film, The Elephant Man, based on the true story of John Merrick, a 19th-century Englishman afflicted with a disfiguring congenital disease. (Actor John Hurt played the role, with the aid of astonishing special makeup work by Christopher Tucker.)

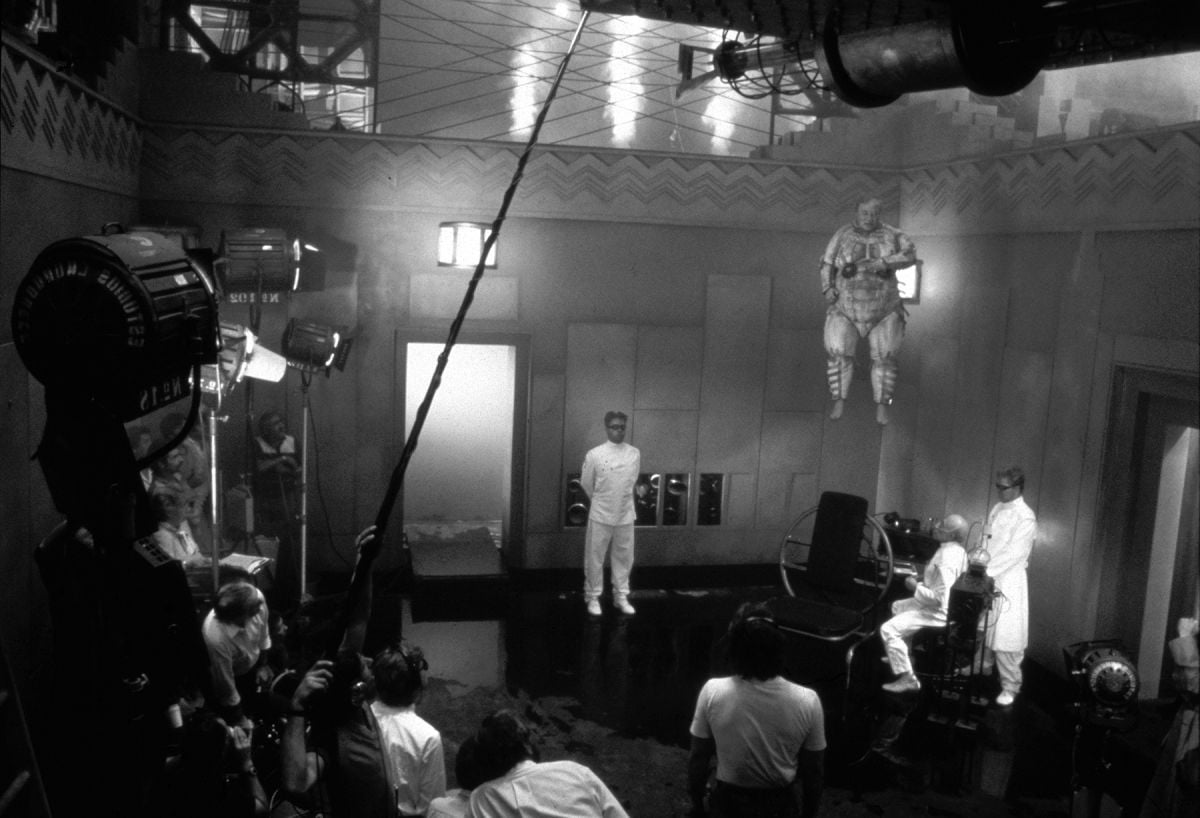

Brooks obtained permission from Paramount to shoot the Victorian-era film in anamorphic black-and-white. Creatively, it was an audacious move, as this combination of formats had not been utilized on a major film for more than a decade; Francis himself had not shot a black-and-white feature in 15 years. But Francis’ work on Sons and Lovers had caught Lynch’s eye, as the director later told AC: “The photography was about light and dark, and it had a mood. It had such a great look that it seemed only natural to hire Freddie.”

The Elephant Man was principally shot at Wembley Studios in Panavision, utilizing Kodak’s Plus X stock — the only monochrome emulsion that met Francis’ standards and was available in sufficient quantities. Due to the dearth of black-and-white features, most of Britain’s labs had let their processing equipment fall into disrepair, necessitating that the cinematographer do extensive tests with several facilities. Rank finally won the contract. Noted Francis in the informative tome The British Cinematographer, “Rank’s processing produced a result which immediately filled me with confidence. My first impressions were that the [Plus X] had increased in speed and that the grain had diminished to such an extent as to be negligible... above all, it was a true black-and-white stock with every minute tone in between.”

Despite this promise, Kodak’s emulsion varied in sensitivity (increasing by a full stop at one point), and Rank had some problems in delivering the image quality that Francis demanded. However, as audiences would attest, the efforts paid off, resulting in an evocative film which retains a haunting, dreamlike textural quality while effectively rendering the gritty reality of the story and setting. “People gave me far more credit for that film than I deserved,” Francis submits. “David knew what he wanted and I was able to show him how to get it.

“There was one shot that absolutely drove us mad though,” the cinematographer remembers. “We were shooting in this old hospital, within a corridor that was about 60 yards long with gaslight fixtures running all the way down. In the shot, a nurse comes along and turns off the lamps one by one, with the hall gradually becoming darker. The obvious solution for the lighting was to use dimmers, but people hadn’t used dimmers for a long time because in color photography they change the color temperature of the light. Of course, we were shooting in black-and-white, so that didn’t matter. We had to scrounge up all of these rusty old dimmer units. We needed a lot of them, and the noise they created was terrible!”

After a long absence, Francis was back at the forefront of his field, and subsequent productions would cement his reputation as one of cinematography’s finest practitioners. One of these triumphs, director Karel Reisz’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman, consists of a film-within-a-film of a story set in 19th-century England.

The period tale concerns a man who is engaged to be married but has a passionate affair with another woman, and the actors who portray the illicit lovers go through a relationship which parallels that of their characters.

To help differentiate the picture’s dual stories, which both starred Jeremy Irons and Meryl Streep, Francis used a Lightflex to desaturate colors and decrease contrast in the film-within-film segments. The on-camera accessory was invented in 1972 by Gerry Turpin, BSC (who would later shoot one of Francis’ last films as a director, The Doctor and the Devils, in 1985). The Lightflex consists primarily of an oversized filter-hood faced with optical glass. Dimmer-controlled quartz lamps built into the hood reflect into the lens and overlay a controlled amount of light on the scene to be photographed at the time of exposure. The device can be used to adjust the gamma curve of the emulsion, and also extends its photometric range without affecting grain.

Francis would come to regularly use the Lightflex, which became an integral part of his photographic process. This apparatus was later developed into the Arriflex VariCon. “I found the Lightflex to be an absolutely fantastic tool,” the cinematographer says. “After Arriflex bought and improved the design, Volker Bahnemann of Arri New York sent me one of my own. I don’t think many people use them, except for students. They’re always ringing and asking me if they can borrow mine!”

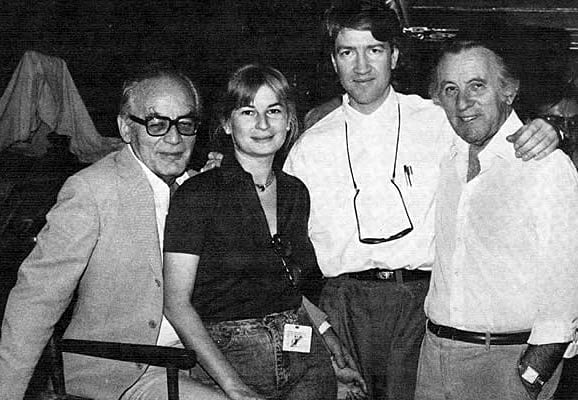

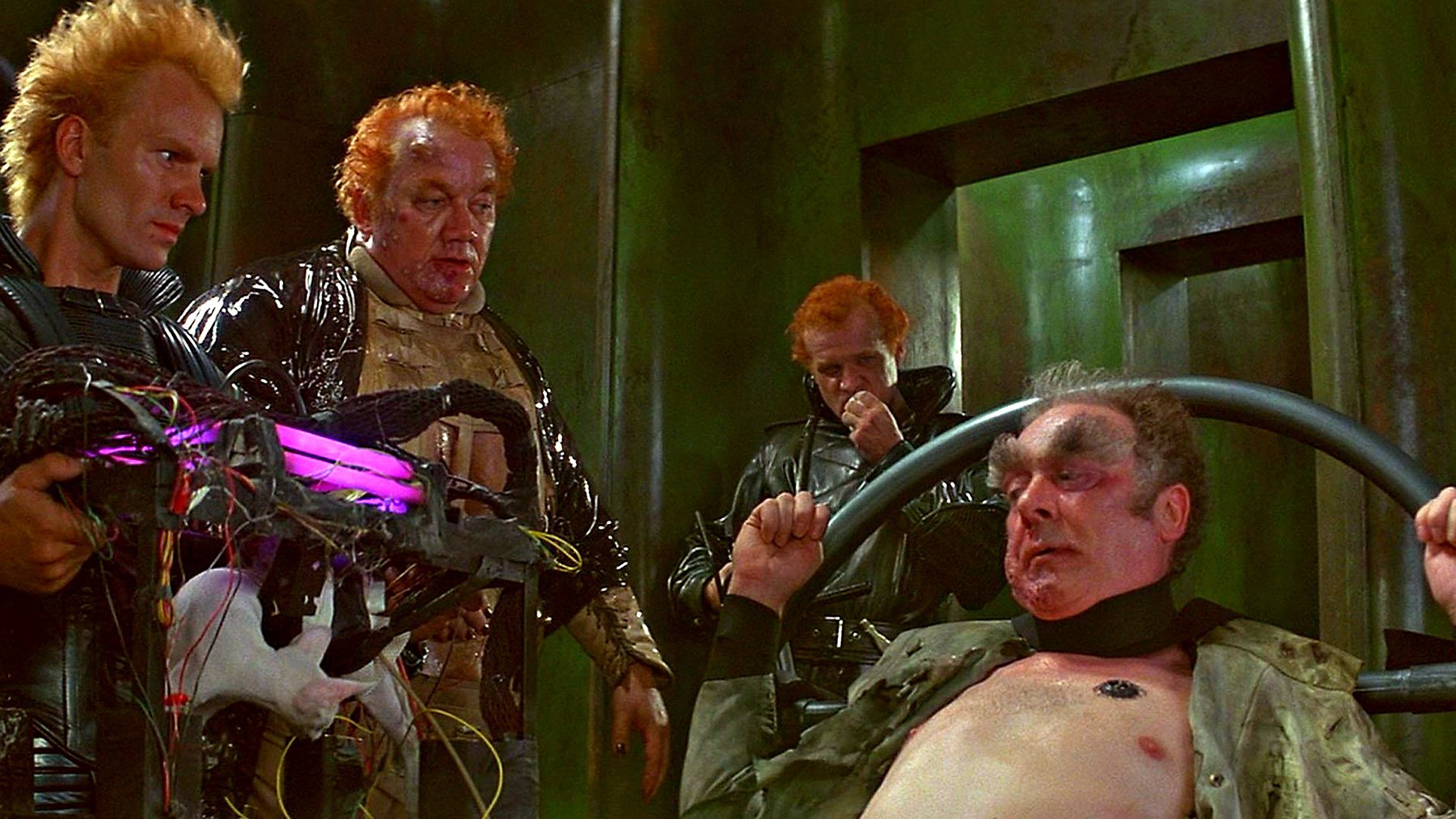

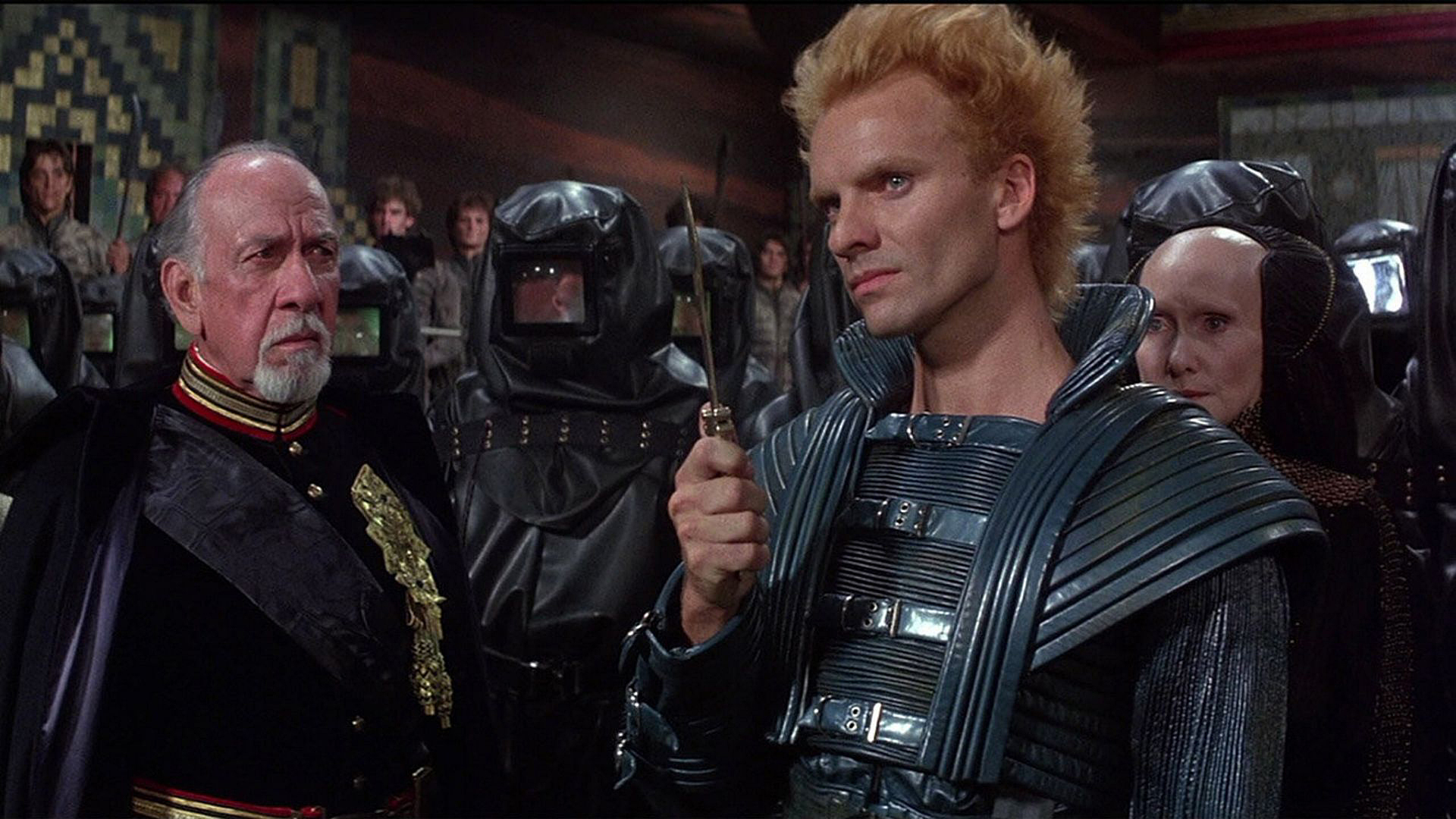

Francis collaborated with Lynch again on Dune (AC Dec. ’84). Based on the novel by Frank Herbert, the dark science-fiction fantasy is set in the far future, as a young man recognizes his inner spiritual power and leads an oppressed people against their enemies. The cinematographer recalls, “Because I had worked with David on The Elephant Man, we didn’t have to discuss the lighting plans a great deal, since I knew the things he’d like. David thinks in black-and-white, so we went very low in key for color, though sometimes hardly as low as he’d have liked to go.”

Featuring stunning photography and production design, Dune was shot in Todd-AO 35 over the course of a year at Mexico City’s Churobusco Studios. Seeking to bring out background detail and desaturate colors to create a more monochromatic image, Francis again employed the Lightflex, which also helped the cinematographer determine his lighting approach for the production’s many intricate sets and expansive locations. Utilizing the device’s ability to open up shadows, Francis could effectively create a four-stop exposure range, even while using the contrasty, high-speed stocks available at the time. This allowed him to use far less fill light, yet shoot at deep stops. Additionally, he could tint scenes in the appropriate hues by inserting gels into the Lightflex’s filter slot, an invaluable tool given the myriad worlds depicted in Dune.

However, the complicated production on the visual effects heavy film was hardly to Francis’ liking, since so much of the imagemaking process would be completed by others in post. “I don’t care much for effects pictures,” he admits. “But David and I had become close friends after The Elephant Man, and I did it because of that friendship.”

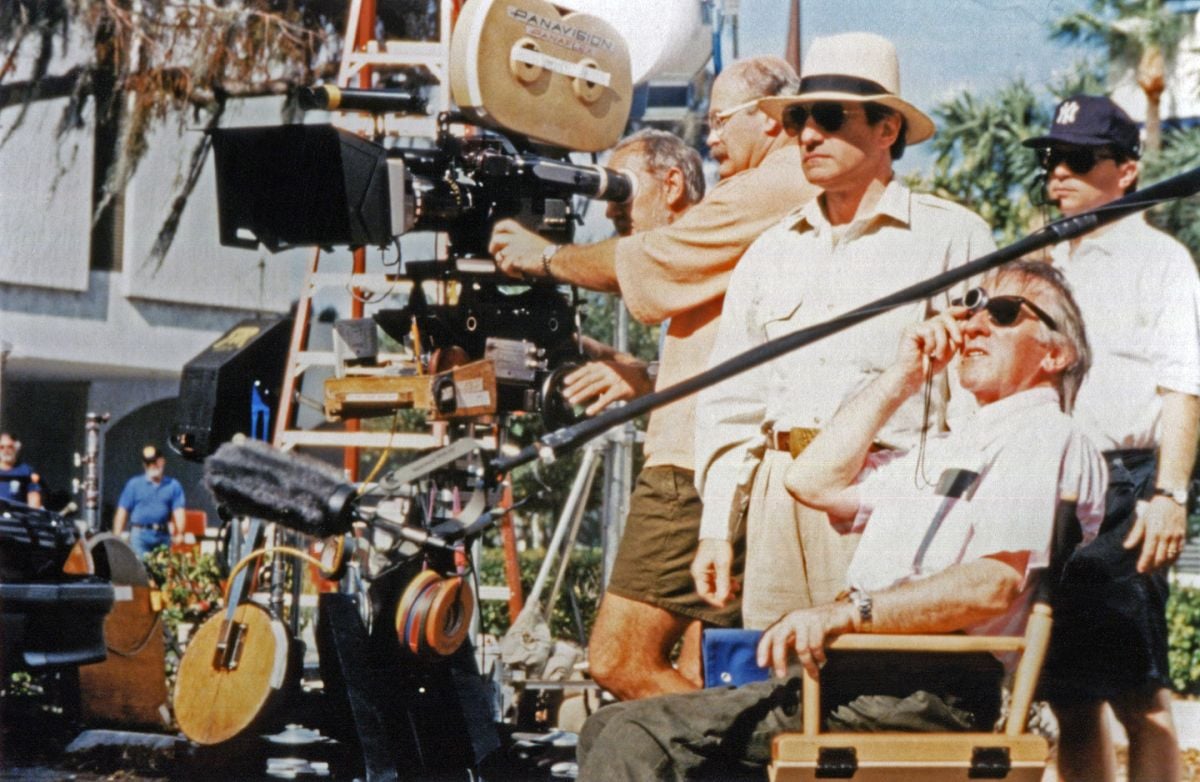

The gripping Civil War drama Glory (AC Nov. ’90) was based on the letters of Colonel Robert G. Shaw (portrayed in the film by Matthew Broderick), an officer in the Union Army who volunteered to lead the first company of black soldiers against Confederate forces.

Seeking an authentic feel for this historical story, Francis and director Edward Zwick studied period stills by famed photographer Matthew Brady and others. The stark black-and-white images suggested a realistic approach devoid of filtration or sepia tones, relying instead on the credibility of the locations and production design to simulate the era. Photographically, Francis rendered Glory simply and honestly, with much of the intimate drama revealed in the light and shadow playing upon soldiers’ faces.

During the film’s conclusion, Shaw and his troops engage in a fateful nighttime battle, which the production staged on the beaches of Jekyall Island, located off the coast of Georgia. Twin Muscos were set hundreds of yards away to create a soft overall ambiance, while assorted pyrotechnic and lightning effects dramatically lit the landscape. The extreme contrast was dampened with the Lightflex, which additionally allowed Francis to shoot at higher stops. The added depth of field allowed the camera to clearly record the human drama. “I’m a great believer in the futility of war,” the cinematographer says, “and I believe we captured that idea quite well in several parts of Glory. That was always in the back of my mind.”

Earning the Academy Award for this picture made Francis one of the few cinematographers to have won for both black-and-white and color camerawork.

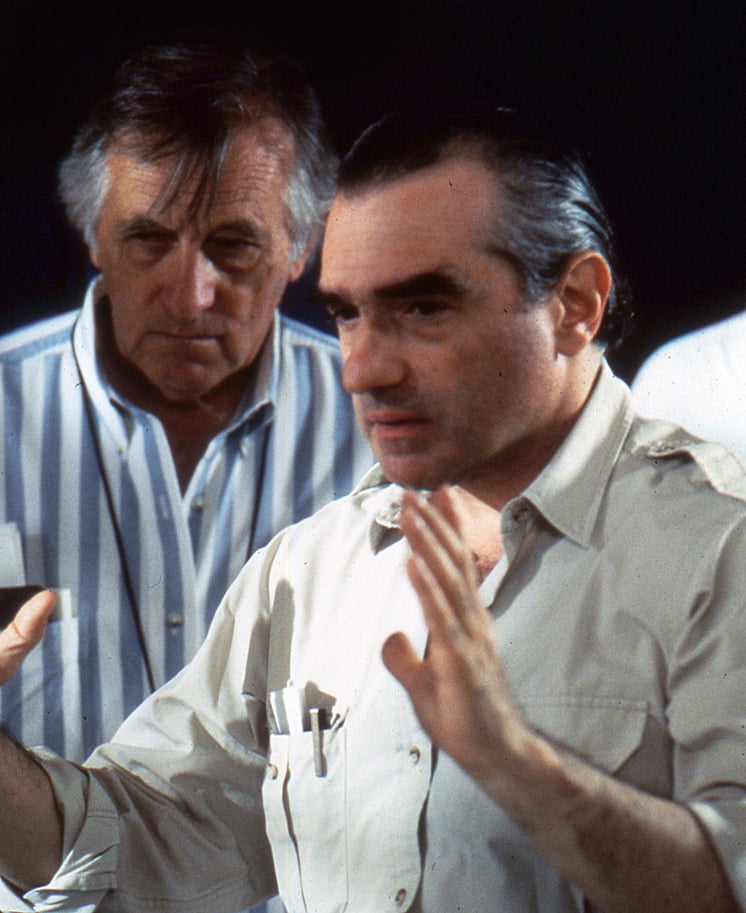

Francis later shot the remake of Cape Fear for director Martin Scorsese (AC Oct. ’91), who had specifically sought the out the cinematographer due to his well-established ability to create a sense of Gothic atmosphere. However, the cinematographer has another theory: “Scorsese was a good friend of Michael Powell’s toward the end of his life. Micky was a fan of mine, and I’m sure he put in a good word for me.”

Shooting the picture in Panavision anamorphic, Francis again sought to utilize deep focus in order to keep the audience anxiously searching the frame for the psychopathic Max Cady (Robert De Niro), who frequently lurked in the shadows. “The only problem we had on that film was in getting quality lenses,” he says. “Nobody had shot in anamorphic for years and years, but when we started that picture, everybody suddenly wanted to do it! It was very difficult to get good lenses.

“Scorsese is another director who has shot the film in his head before you’ve exposed a single frame of film,” Francis remarks. “You can sometimes talk him into something, though. There was one scene with Bob De Niro where he’s talking on the phone, hanging upside-down from a bar strung across a doorway. I suggested that we start the shot upside down, tight on his face, and then rotate the camera as we tracked backwards so the room would become upside-down. We did that shot with a Panatate remote head, and Marty just fell madly in love with the thing.”

The film’s harrowing climax, a brutal fight set aboard an out-of-control houseboat drifting down the Cape Fear River in the midst of a storm, was shot in a specially built studio tank facility. The Panatate was often employed to create violently twisting and rolling camera moves that enhanced both the fight’s visceral impact and the storm’s fury. “We used it so often that I told Marty, ‘If I could afford it, I’d buy you one of these for your birthday!”’ Francis says with a hearty chuckle.

Looking back on his career, Francis ponders the technological changes that have been made since his start in the 1930s. Scoffing at the notion that cinematography is an inherently technical field, he offers, “If someone asks me, ‘I loved that shot, how did you light it?’, I’ll think they’ve lost the point. My explanation doesn’t mean a thing because there are 20 ways to light a shot and get the same result. Why you do something is far more important than how. The cinematographer is a storyteller, and his main job is to communicate with the director and get his ideas on the screen. I just always insist on having a wonderful operator and wonderful gaffer. I can tell them what I have in my mind and they’ll know what to do, with me just adding a few touches later.”

Again evincing a grin, Francis concludes, “There are no rules and there is no formula to filling the frame to please everybody. I’ve got this corny saying though: ‘There are three types of photography: good photography, bad photography and the right photography. The right photography is what tells the story best.’”

Soon after the publication of this article, Francis would shoot his last feature film, the heartfelt portrait piece The Straight Story (1999; AC Nov ’99), for director David Lynch.

He received a call and then the script from the director in the summer of 1998, just six weeks before the start of principal photography.

Eager to work with Lynch again, Francis didn’t hesitate to accept the project, but he did request a maximum 10-hour shooting day. A spry octogenarian, Francis asserted, "I'm not doing 16- or 17-hour days anymore, but even at 10 hours, we still came in two or three days under schedule on the six-week shoot. There must be a moral there somewhere!"

The cinematographer completed his autobiography — Freddie Francis: The Straight Story from Moby Dick to Glory, a Memoir (with forwards by David Lynch and Oswald Morris, BSC) — shortly before his death on March 17, 2007 at the age of 89.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.