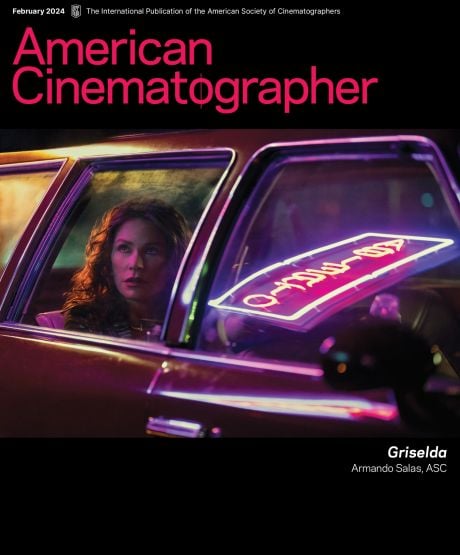

Camerimage 2018: Witold Sobocinski, PSC

Honoring the renown Polish cinematographer and 2018 Camerimage Lifetime Achievement Award honoree. UPDATE: Sobocinski died on Nov. 18 at the age of 89.

In honor of this year’s Camerimage Lifetime Achievement Award honoree, we re-present this career-spanning profile published by AC in March of 2003, when he was honored with our International Award during the 17th annual ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography. The cinematographer was perviously honored by Camerimage in 1994.

Footsteps Worth Following

The ASC presents its International Award to the esteemed Polish cinematographer whose work has had a global influence on the art of filmmaking.

Last month, Witold Sobocinski, PSC became the first recipient of the ASC International Achievement Award whose main body of work falls outside the sphere of Western filmmaking. The award is given annually to a cinematographer who creates an extraordinary body of work outside the United States; previous honorees include BSC members Douglas Slocombe, Oswald Morris, Billy Williams, Freddie Young, Jack Cardiff and Freddie Francis; Giuseppe Rotunno, ASC, AIC; Gabriel Figueroa, AMC; Raoul Coutard and Henri Alekan.

“Witold Sobocinski isn’t as well known as he deserves to be in the United States because most of his films were made in Poland at a time when political barriers blocked the free exchange of ideas,” says Owen Roizman, ASC, chairman of the ASC Awards committee.

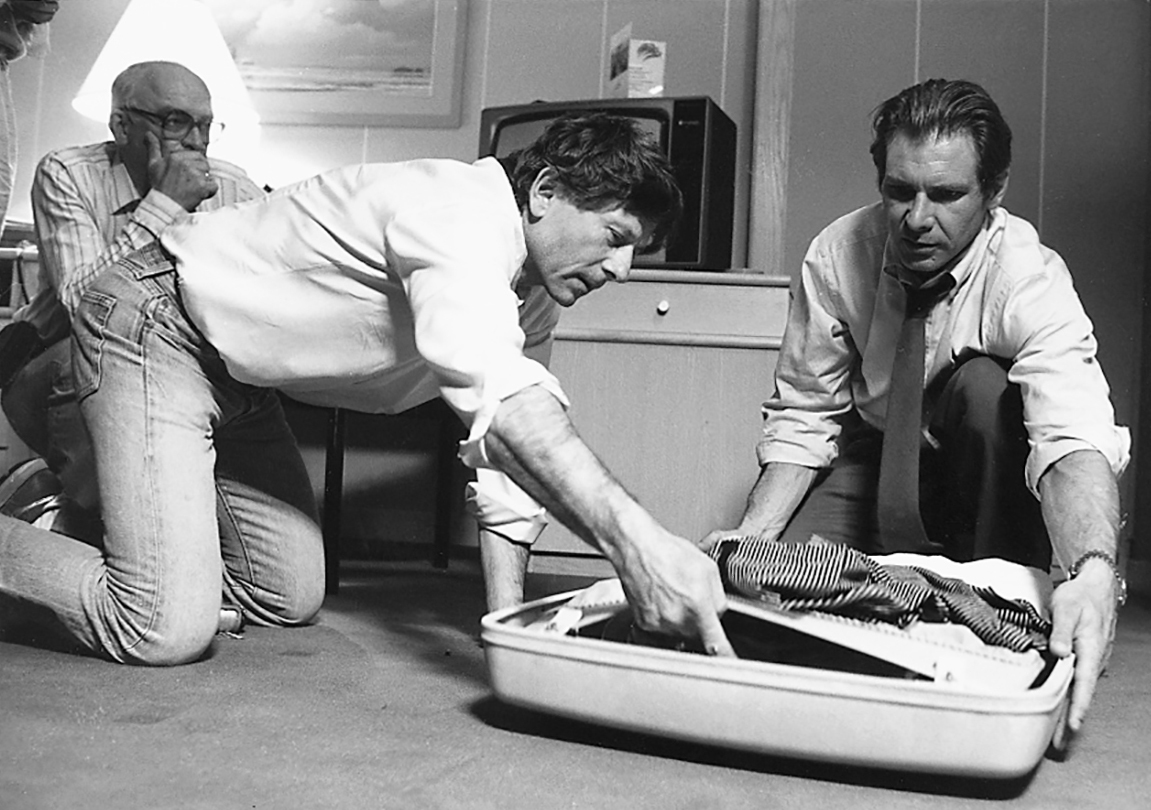

In spite of this, Sobocinski has managed to make his influence felt through films made in Western Europe, including Frantic, directed by Roman Polanski, and through the work of his students and collaborators, many of whom have advanced to successful careers on the world stage. “Cinematography is truly a universal form of artistic expression,” says Steven Poster, ASC. “Like music, it crosses boundaries imposed by language and geography. Cinematographers communicate with audiences in a silent language, and Witold is truly a master of this art form.”

Sobocinski was born in Ozorkow, Poland, in 1929. He was 10 years old when Nazi armies invaded and occupied his native land. Six years later, Russia pulled Poland into its political orbit and kept it isolated from the West for decades. “I am a child of war,” says Sobocinski. “Everything that happened in my life is in that context. Naturally, all of us who lived through the war wanted to even out accounts through our work. The famous Polish film school had its beginnings in this urge. The Polish people, because of our experiences during and after the war years, were probably uniquely qualified to examine the war through art, and that was one of the elements that helped make Polish post-war cinema famous.”

For Sobocinski, like many Eastern Europeans of that era, American jazz music was an obsession, a way of resisting the authorities. Sobocinski recalls hiding under the covers in his bed as a boy, listening to jazz on the Voice of America on a homemade receiver. Later, he played drums in a jazz combo. “We weren’t a very good jazz band,” he recalls, “but we wanted to try everything that we could, no matter how difficult. That is how we learn. What we played was merely an echo of the beautiful music we heard.

“Later, when it came to filmmaking, I found a similar way of learning,” he says. “I think of my images in a musical way. The Marriage, which I consider to be one of my most interesting films, is a good example of this musical approach. On the page, this story is completely dead — nothing happens. But in the film, the rhythm of the images brings it to life. As a movie, The Marriage gets a very high ranking. Jazz taught me to make films by feeling them. I could never get jazz out of my head, and it informs all of the images I’ve photographed over the years.”

When Sobocinski applied to film school, his musician friends were disappointed. He says that during the war, the Polish people didn’t see narrative films. Newsreels were projected in the cinemas, however, and Sobocinski recalls seeing footage from the brutally repressed 1944 Warsaw uprising. “I remember seeing the Polish people giving their weapons back,” he says. “That remained in my memory and came back to me in later years.”

Sobocinski was among the first generation of students drawn to the National Film, Television and Theatre School in Lödz after it was organized in 1948. The school attracted writers, musicians, composers, actors and filmmakers, and became a cultural center for artistic expression.

Sobocinski was accepted into the film school at a time when only one out of every 400 applicants made it through the rigorous selection process. Along with his schoolmates, he learned by watching the films of Chaplin, Eisenstein and Murnau. But his world was changed forever the day he saw Citizen Kane.“That film never leaves me,” he says. “It is present in all my ideas, even today. Citizen Kane was a revolution in how to create a film. Filmmaking is collective effort, but with Citizen Kane, Welles [and Gregg Toland, ASC] created a new cinema. It brought together all the howls in the night that had existed previously and formed them into a stronger unity. Prior to Kane, we had action, melodrama and happy endings. This was something completely different, and I never thought about film the same way after that.”

Sobocinski points out that the Polish film school placed great emphasis on “the humanistic point of view.” Students were thoroughly versed in the history of art, and filmmakers were educated as “whole artists.” He concedes that “the ABCs of technique must be mastered, of course. But in my experience, once you master the technical aspect you must throw it away. If you make it far enough, you’re no longer a technician or an engineer; you’re something beyond that. You’re a filmmaker.”

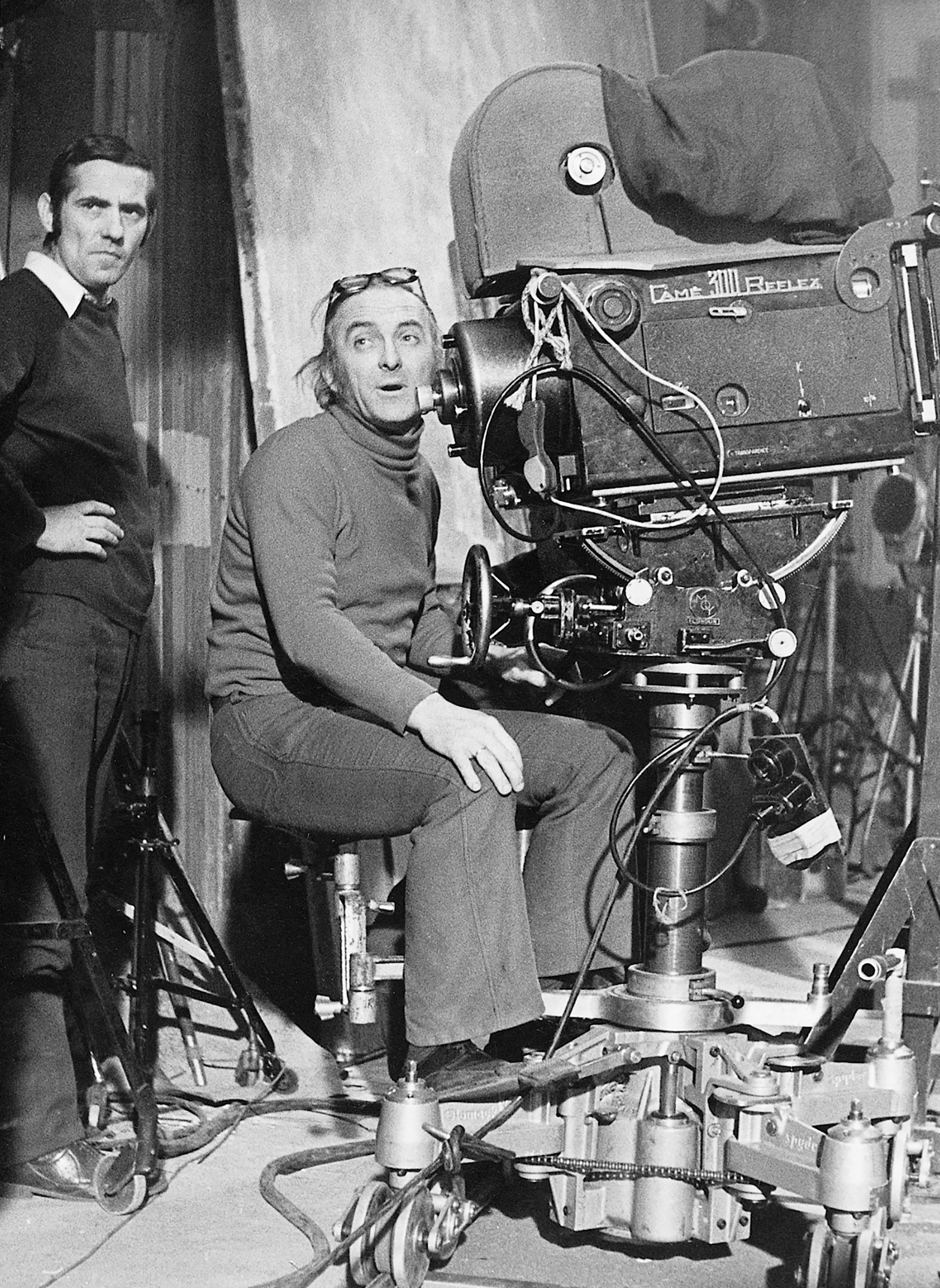

During his student years, Sobocinski began his lifelong collaborations with a new generation of directors who were nurtured at Lödz, including Polanski, Andrzej Wajda, Jerzy Skolimowski and Krzysztof Zanussi. After graduation, Sobocinski and his colleagues made films that surreptitiously addressed the war and its aftermath. Filmmaking under the circumstances was a political act, he says. Polish filmmaking of that era, like much art under the thumb of the communists, developed a subtext in which coded messages were delivered through the use of allegory and symbolism. The trick was to communicate a message without attracting the censors’ attention. Making such statements was a brave act, considering the consequences of being caught. Sobocinski saw colleagues sentenced to long prison terms for their artistic creations. “The censorship was very, very strong,” he recalls. “It was forbidden to make films about contemporary subjects unless they were in praise of the current regime. One of my best films, The Hour-Glass Sanitorium, was smuggled out by the director and taken to Cannes. There is no other film like it.”

Sobocinski’s early cinematography credits include Dancing wkwaterze Hitlera (Dancing Party in Hitler’s Headquarters) and Zycie rodzinne (Wednesday’s Child, a.k.a. Family Life). In 1974, he collaborated with Wajda on Ziemia obiecana (The Promised Land), which was nominated for an Oscar in the foreign-film category. For Wajda, it brought some yearned-for recognition in the West, but Sobocinski remained a relative unknown outside Eastern Europe. “In places like Cannes and Hollywood, the director got all the recognition,” says Sobocinski. “There was never a question of the director of photography going to Hollywood. It’s only quite recently that foreign-made films get Academy Award nominations in categories like cinematography.”

Sobocinski notes that Poland viewed the Cold War from a unique position at the crossroads of two cultures. “Being carved out of two countries and fought over for centuries was a major problem for Poland, to say the least, but it also meant that we saw things from an unusual perspective,” he says. “With this in mind, you can understand how different our way of narrating is. We are a meeting of two cultures, and I am a human example of that.”

During the 1970s and ’80s, Sobocinski had occasional opportunities to work on films produced in Western countries, including The Catamount Killing (Germany), Wege in der Nacht (Ways in the Night, Germany), Pirates (France and Tunisia) and Frantic (United States). The latter two films were directed by Polanski, who had made a number of critically praised films in the United States.

Sobocinski says that Eastern European filmmakers tend to shoot less coverage, making decisions at the script or shooting stage that their Western colleagues might save for the editing room. “With my background, I learned to shoot fast, and Western productions liked that,” he says. “It was an advantage for me. But I sometimes found that directors wanted a technical contribution from me with less emphasis on participating in the creative process. I understand that this is a different way of working, and I can do that, but it doesn’t give me the creative satisfaction I desire.”

Sobocinski’s career has seen much advancement in the technology behind filmmaking. One of the biggest was the advent of color film stock. He says that while these changes were welcome, they didn’t change the creative act of filmmaking. “Yes, everything in the world changes,” he says. “Styles change, the way narrative works can even change. The companies that work with us give us much better tools now. On the surface, things seem to get easier. But the new machines only make the labor aspect go faster. The thinking process is the part that takes time, and that has not changed. The human contribution remains the same. I always say that what we give to a film is our time and our health; that doesn’t change in spite of the many great advancements in technology.”

Sobocinski has dedicated most of his time and energy over the past two decades to passing his expertise on to younger generations of filmmakers. He has taught many of the best Polish filmmakers at the National Film School. His students and acolytes include such world-renowned cinematographers as Janusz Kaminski and Slawomir Idziak, PSC. “I’m not a born teacher,” says Sobocinski. “I feel my job is to prepare these young people for real work. I want them to be firmly rooted, with their feet on the ground, so to speak. After 20 years, I can say how precise and far-thinking this approach has been. Many of the 500 or so students we have taught in that time are working now, all over the world.”

Sobocinski says his late son, Piotr, who died in 2001 at the age of 42, was among his most promising students. The junior Sobocinski spoke about his father at Camerimage in 1995: “I don’t remember my father talking to me about cinematography on a technical level. He told me that wherever you are standing, you can take pictures 360 degrees in any direction. He said you have to eliminate what is not necessary and find the right angle. He taught me that the language of film is your own interpretation of reality. You have to select what is important from the jumble of images we see in our everyday lives. You can speak without using words by the decisions you make.” (Today, Piotr’s own son, Michael, is following in his footsteps as an aspiring cameraman. Profiled here as one of AC’s 2018 Rising Stars of Cinematography.)

Sobocinski’s contribution to the world of cinematography is also visible at Camerimage, the International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography, which was inaugurated 10 years ago in Torun, Poland. He was president of the Polish Society of Cinematographers when the event was conceived and played a crucial role in helping festival president Marek Zydowicz make it a reality. Now held in Lödz, Camerimage is the only major festival that focuses on cinematography as a global art form. Part of the vision for the festival was to provide a forum where cinematographers from different cultures and countries could meet.

In 1994, Camerimage presented Sobocinski with a Lifetime Achievement Award. “It was the first time that many cinematographers and film critics from around the world had an opportunity to experience and appreciate a broad selection of Witold Sobocinski’s work,” says Zydowicz. “That gave many of them the first true measure of his talent and his influence on the art form.”

“The most wonderful aspect of the Camerimage festival is its spirit of collaboration and camaraderie, rather than competition,” Sobocinski says. “It’s a step toward teaching film lovers the huge responsibility carried by the director of photography. It’s hard to grasp, but the festival is making progress.”

Sobocinski’s most recent film was 1999’s Wrota Europy (The Gateway of Europe), which earned the Best Cinematography Award at the Polish Film Festival and was nominated for a Camerimage Golden Frog.

The cinematographer says his greatest regret is that many of his best films have never been exhibited in the West. “When I first began working, we knew that this type of work couldn’t be shown outside of Poland because it would have demonstrated that we could do good things with the ‘decadent’ art of the West,” he says. “It’s wonderful to receive this award from the ASC, and I am grateful. Film is always being changed through the influence of outsiders. Throughout its history, Hollywood has adapted foreign influences and brought them into the mainstream. The biggest reward for me would be to have my colleagues in the Western world see my work, and to know that my work helped change the American way of filmmaking.”

Idziak, an Academy Award nominee last year for Black Hawk Down, recently gauged Sobocinski’s impact on him and on world cinema: “My personal association with Witold Sobocinski has had enormous influence on me as a filmmaker, and my decision to work as his camera operator on The Wedding was a turning point in my career. Of course, I learned enormous lessons from him about the nature of filmmaking. For me, this was a giant step forward. After this one professional encounter, I returned to my work as a director of photography with my personal perspective totally changed, and for this I am deeply indebted to him.

“More importantly, through his films, his teaching and his students who work around the world, he has given the entire world of cinematography invaluable lessons about the nature of cinematography and the responsibilities of its practitioners,” Idziak continues. “In photographing The Wedding,for example, he approached the use of color in a completely new, independent way. He forgot about any realistic representation of color and tried to use it as a dramaturgical tool. In this, he was influenced by the modern paintings of the early 20th century. I remember a French film critic being amazed by this unprecedented use of color. The Wedding was a stage play that was totally static and based on words, and Witold somehow translated that into a very dynamic vision. He was the real father of this kind of approach, and today its influence can be felt in the work of many important filmmakers.

“Looking at Witold’s films, we see that he believed each picture required a new way of seeing and thinking, that each story needed to be served in a unique way,” says Idziak. “He showed us that the director of photography should be the first person to be engaged after the decision to go forward with production. Right now it’s especially important for the cinematography community to understand the lessons Witold taught us, because at this moment we’re facing a technological revolution that presents us with a perfect opportunity to question every aspect of the system in which we work. Witold taught us that the cinematographer offers much more than technical knowledge — he taught us that it is the cinematographer’s responsibility to fight for a vision, to persuade the director rather than to merely do his or her bidding. He was among the first to advance the idea that the cinematographer is the most important collaborator after the director. He showed us that this meeting could be the backbone for a new model of cinema.”

•••

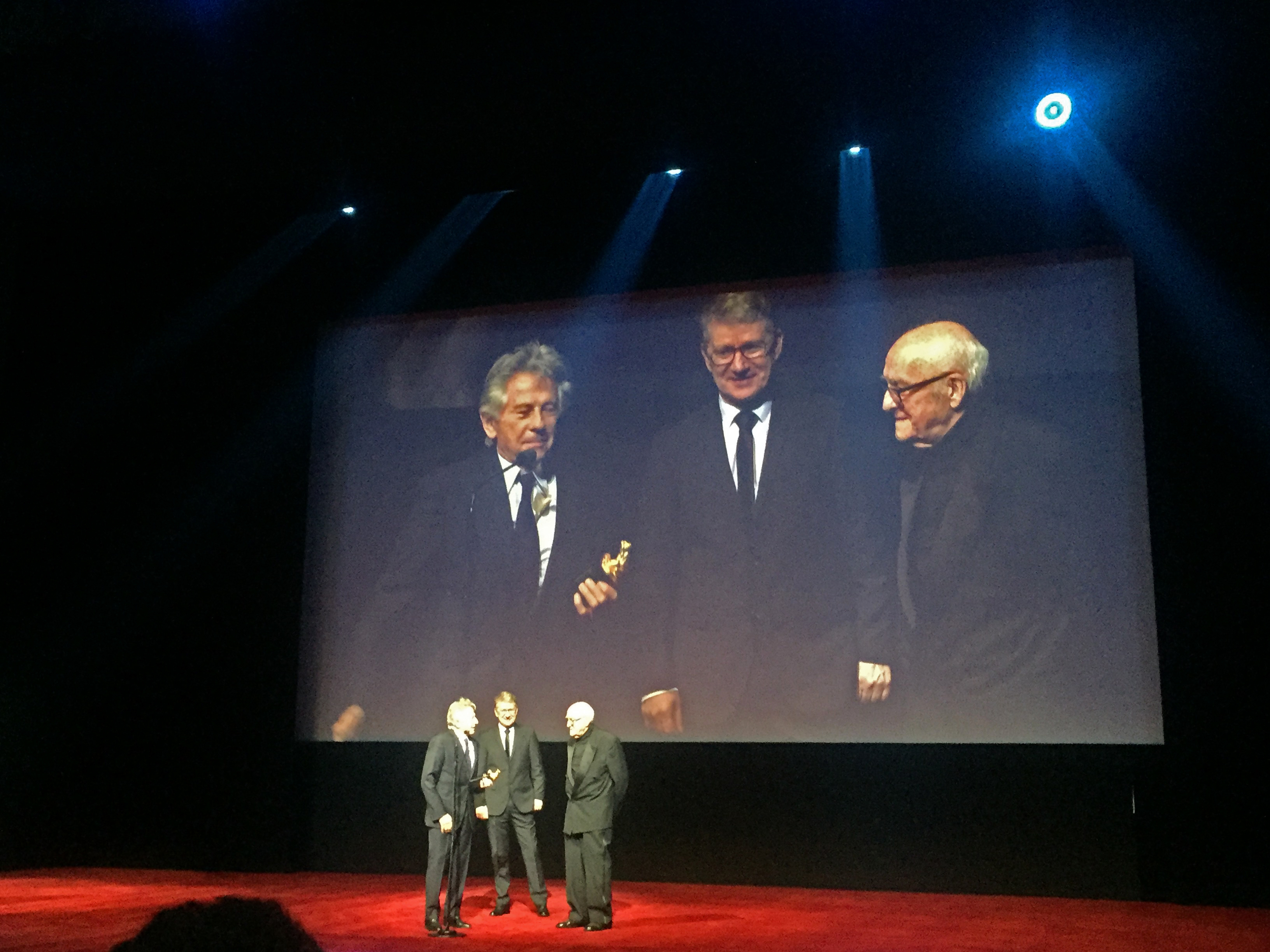

Sobocinski received the Camerimage Lifetime Achievement Award on November 10 during the 26th Camerimage International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography in Bydgoszcz, Poland. He was presented with the Golden Frog trophy by frequent collaborator and longtime friend Roman Polanski:

Tragically, it was announced by Camerimage and Polish news sources on November 19 that the cinematographer died at the age of 89.