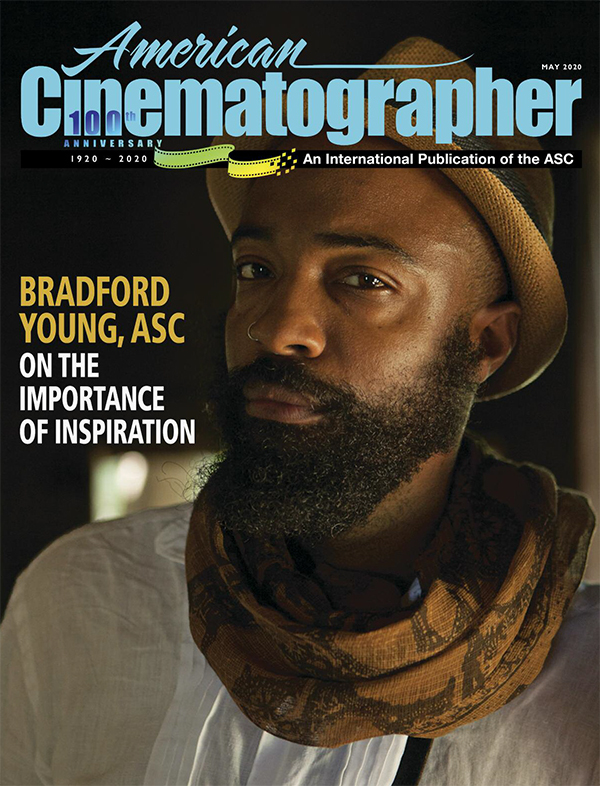

Bradford Young, ASC: The Importance of Inspiration

The cinematographer discusses the life choices, motivations and influences that led him to a career behind the camera.

Many creative people face a crossroads in life, where they must either embrace and pursue their passion or conform to expectations — real or imagined. As a young man growing up in Louisville, Ky., Bradford Young, ASC seemed to have a predestined path — dictated by geography, social pressure and an expectation that he’d take over the family business. But other forces intervened.

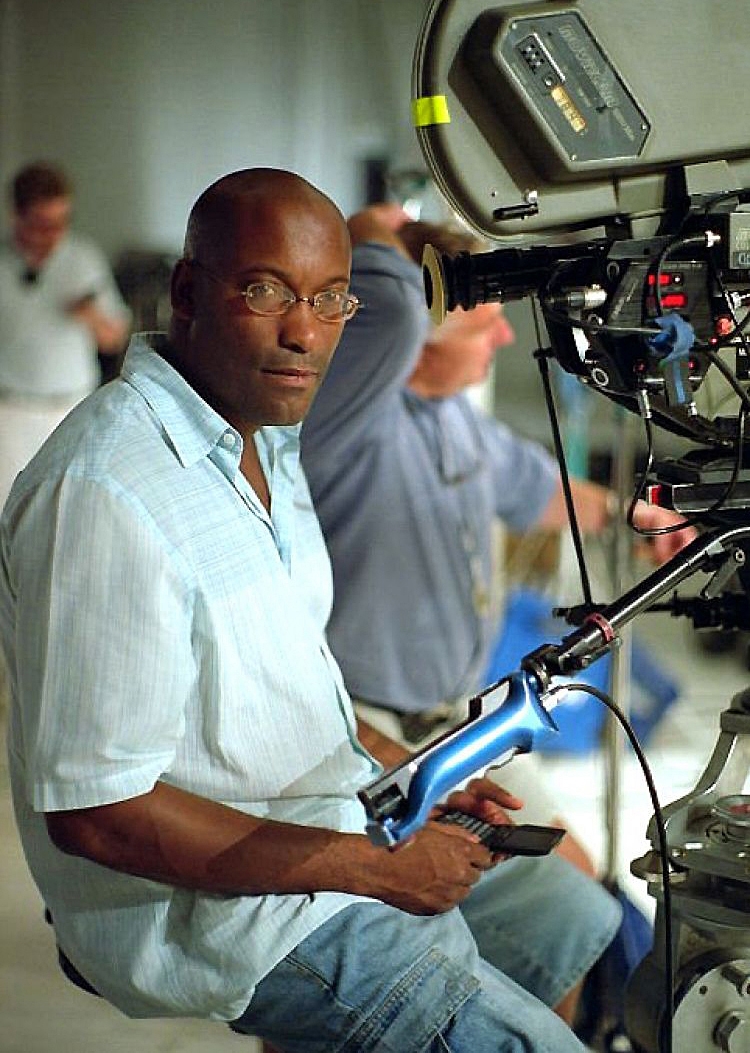

Admirers of Young’s work know that the award-winning cinematographer established himself as a new voice with such independent features as Pariah (AC April ’11), Middle of Nowhere (AC Nov. ’12), Mother of George (AC April ’13), Ain’t Them Bodies Saints (AC Sept. ’13), Pawn Sacrifice, Selma and A Most Violent Year (AC Feb. ’15, the latter two), as well as the big-budget features Arrival (AC Dec. ’16) — for which he earned ASC, BAFTA and Academy Award nominations — and Solo: A Star Wars Story (AC July ’18), and the miniseries When They See Us (for which he earned an Emmy nomination). But few might realize Young’s path to success was far from a direct route.

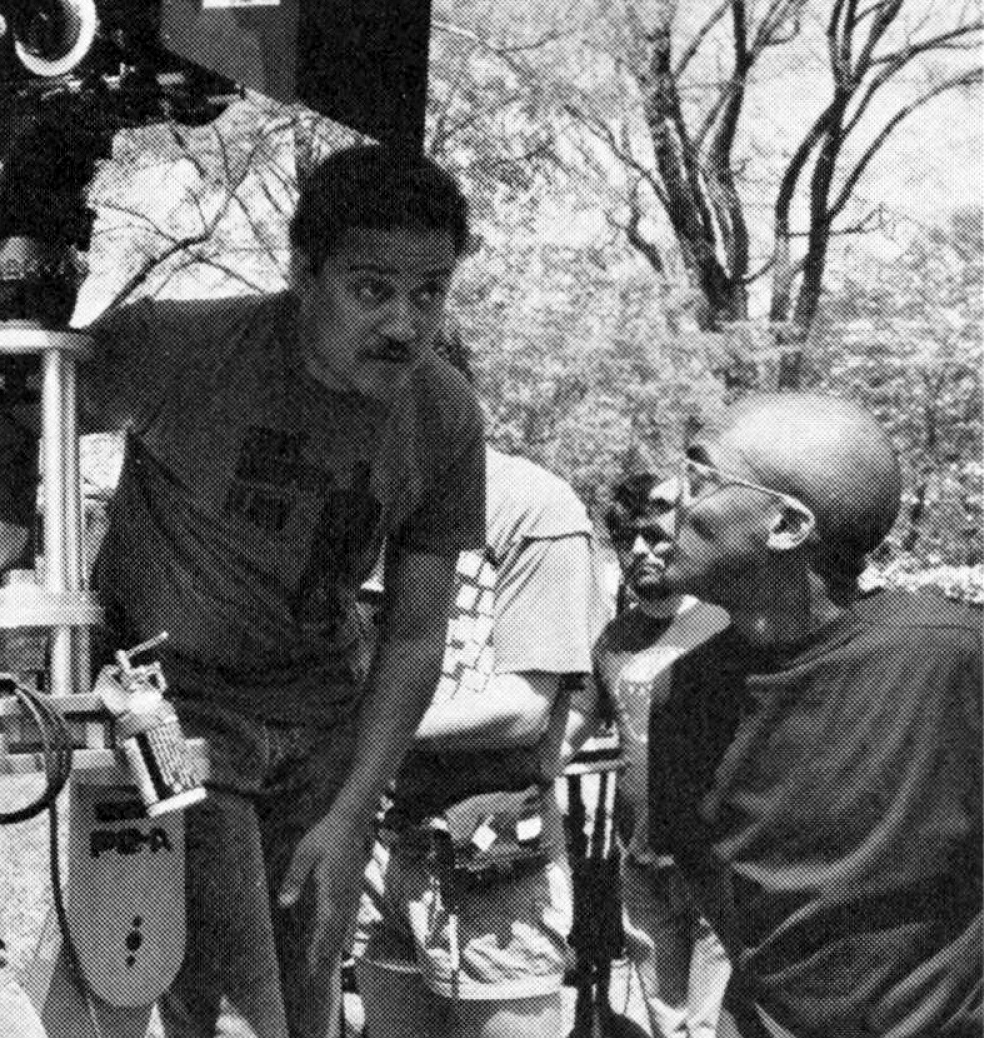

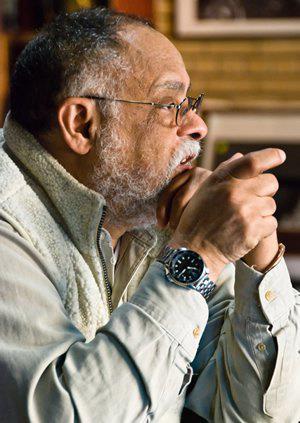

As a student at Howard University, Young studied under Ethiopian filmmaker and professor Haile Gerima — himself a 1976 graduate of the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television — who moved beyond the role of teacher for Young, and became a mentor. Gerima was one of several who would alter Young’s perception of what was possible for himself as an artistic person seeking to tell stories through images.

During a far-ranging interview conducted as part of a forthcoming ASC online education initiative, Young talked at length about how his life was changed by individuals who inspired him, and how those experiences helped him along his journey — one he continues to travel and map.

“I needed somebody to say, ‘You are going to be an artist; you are going to make films.’”

American Cinematographer: When you meet young, aspiring cinematographers, what do they most want to know about you?

Bradford Young, ASC: [Laughs.] That’s a good question, and a difficult one to answer without sounding too presumptuous. When I was an 18- or 19-year-old kid thinking about cinematography as an art form and dreaming about trying to work like I am now — and thinking about even meeting someone like Malik Sayeed or Ernest Dickerson [ASC] — the thing that was really lacking in my life was this feeling of authenticity. I was looking to interact with people who had authentic experiences, and who were using film, cinema or art to map their life experience. If I had to transfer that 18-, 19- or 20-year-old mind of mine into the minds of young people for whom communication and understanding is so much more present than it was when I was their age, I would say that need for authenticity is not something that has gone away. No matter what time we live in, people are looking to make a connection, to have a conversation, even if they are thousands of miles away. In this environment where images are upon us all day, young people still want authenticity.

And we have to talk about demystification. We’re artists working in an art form that — in some areas — is still shrouded in a very mystified way, and seen through a fame-oriented lens. Young people need to know that behind that shroud, behind that curtain, there are real people — people who have their own struggles and questions about their own identity, their culture, the environment they live in. And they are people who wake up every morning excited about participating in this art form because it gives them an opportunity to be their true, authentic selves.

I just try to show young people that I’m a homie — I’m their cousin, their uncle, their father. I’m not any different, and I have the same concerns about my own family, my own children, my partnership with my lovely wife — all the same concerns as everybody else.

Every time that I’m blessed to roll a camera, or have someone roll a camera for me, I don’t take it for granted. It all starts with a single frame, and then 24 frames per second, and I understand the implications of that. I’m hoping that young people I cross paths with — and my elders — understand that I take every moment seriously when we’re constructing these ideas and images.

Many aspiring cinematographers who have been able to meet established professionals in the field — and have a candid conversation — come back with a similar impression: “I can’t believe they have the same problems I do.” Do you still face the same problems that you did in the beginning?

Young: I think that goes back to what I was saying about authenticity — [and the related idea of] vulnerability. [Vulnerability is] the thing we have to access in order to open up our creative senses in cinema, because we’re mapping human behavior in real time at whatever juncture that happens to be in terms of story. Vulnerability is one of our ‘weapons.’ And because I’m always trying to be — even through my own filters — a vulnerable person, that process of learning and making mistakes and failing is ultimately more important than [what] we deem successes or how we [quantify] success.

[When] I wrestled as a young person thinking about imagemaking as the ‘axe’ I use to express my own personal ideas — my personal dilemma — [I found that] vulnerability is that anchor I can stand on while I unpack [whether] the moment I’m dealing with is authentic. So it’s important for us working as professional imagemakers [to use] this craft, this art form, as a vehicle of healing. To help us deal with our trauma. And it’s important for young people to know that all of us — generally, in the Western world — are dealing with the same kinds of trauma. The process of exorcising that is a personalized road, but one we are all on together. Vulnerability can help us open up and access skills, techniques and ideas that are often closed off to us because we’re so protective of our trauma and pain. I just always hope that young people can get that out of the work.

It’s interesting because our contribution as cinematographers is so visible yet so invisible, you know? I sometimes think that aside from actors, we’re the most vulnerable people on the set. And it’s important for folks to know that part of our process is to be vulnerable. Every cinematographer might use a different word to describe how they open up that spirit or internal cosmos to bring forth images, but “vulnerable” is the one I use.

“If you were a young Black person growing up in Louisville and hadn’t seen School Daze, then you had [missed] an authentic Black experience.”

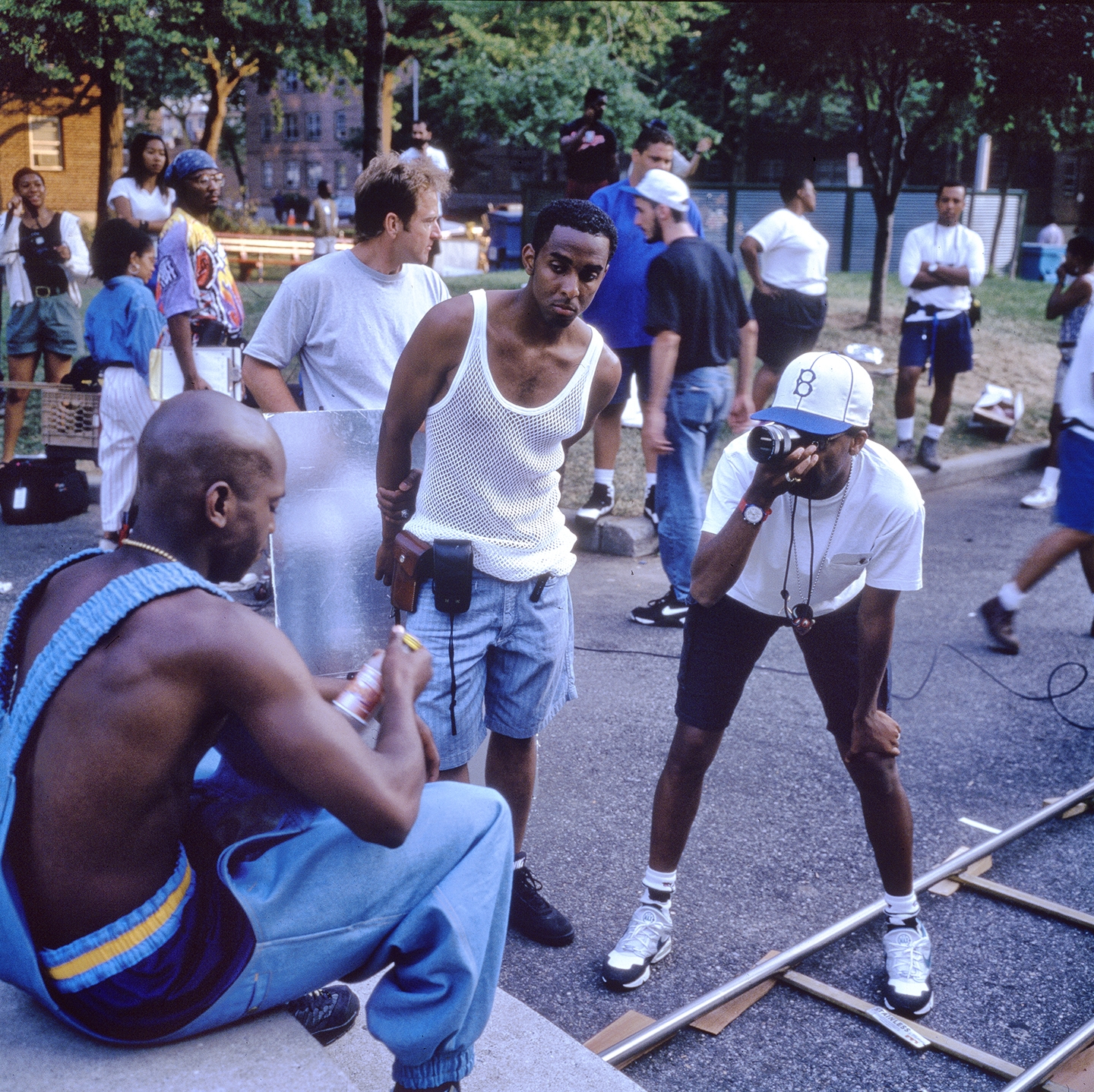

What were some of the first experiences that helped you discover filmmaking as a “thing,” and even something you can do? A lot of people who love movies never make that realization.You’ve said before that seeing Spike Lee’s School Daze [1988; shot by Ernest Dickerson, ASC] was a big moment.

Young: That’s an ongoing [question] that I’ve been having with myself for some time, and its current iteration has a lot of layers. My movie-watching experience as a young Black person in America — and I’m homing in on that word Black with a capital ‘B’ — has colored my engagement with an understanding of film. I’m responding to that now in my current practice. Without it being known to me, the films I saw before School Daze were actually doing things I didn’t know they were doing. I didn’t see myself in the films — I didn’t see my family or my community or things I cared about. As an American child, [I felt] they [offered] a certain amount of escapism and gave me joy — made me laugh and cry — and that all felt right. It was a communal experience, and we’d share a box of popcorn and have a great time. But School Dazechanged all of that, on several levels. First, if you were a young Black person growing up in Louisville and hadn’t seen School Daze, then you had [missed] an authentic Black experience. You needed to go to a theater because this young Black filmmaker named Spike Lee made this for you.

That was the first time that I experienced film as a movement. I wasn’t aware of that [idea] then, but I was aware that everyone was talking about this film. I went with my mom, and my sisters who were a little older than me, and I saw my friends in the theater. It was the first time I went to the movies and saw only Black families all in one place watching something specifically made for a Black audience. I’d gone to the movies 100 times and never seen [that happen] before. Not for The Goonies, not for Return of the Jedi — none of that. But for School Daze, everybody was there, and I remember that resonating with me because I felt like I was sharing something with them. And then the film came on.

Now, my grandparents were relatively affluent, and they stressed to us that culture was important. So I met artists at their house, I went to art-gallery openings, I went to the opera and saw Porgy and Bess. That was part of our rearing, and it seemed natural. So as a young person, I had some understanding of art. But this film had a temperament and patina to it that I had not seen before. First of all, the skin tones. I remember thinking you could almost eat them; you could grab them off the screen.

I couldn’t stand musicals growing up, but this film’s blend of drama and musical was enjoyable, which was new to me — maybe because it was surrounded by so many other new things. It was about a historically African-American college. Most of my family had gone to historically African-American colleges and universities, so that experience was familiar to me. This film had all these things working on me — just like so many other movies I’d seen before — but this one was manufactured for me, as a young person in a movie theater. That really brought up a lot of questions and left a deep etching on me. The one thing I could not communicate then that I can now is that that film was made for us.

That’s something we in the Western world struggle to talk about — films made for a specific audience. It’s counter to commerce. It’s counter to the idea that we have exorcised these things out of our culture, when we have not. And it [leads] into the conversation about representation. Why it’s important for women to make films about and for women. Why it’s important for Italian filmmakers to make films about that experience. Why it’s important for Chinese filmmakers to make Chinese films. These are things all filmmakers wrestle with, and it was exemplified, for me, when I first saw School Daze. It was clear that Spike Lee made that for me, but that it also spoke to all the other people in the theater, and that showed me the power of film. If you look at the current landscape of people of color making films, I’m confident that School Daze was an influence on their pursuit to become a filmmaker or storyteller.

What did the young Bradford Young do with this epiphany?

Young: [Laughs.] First, I ran away from it, because I’m the grandson of a mortician, and my grandfather was a very powerful presence in my life. Not in a million years did I think I could be an artist. So whatever feeling I was having was put away in a bag, to its ‘proper’ place, to the side, because … like many of us, I felt the heavy weight to fulfill a family responsibility. I was expected to take over the family business. I felt that burden, even though it was totally unsaid and unspoken. My great-grandfather and grandfather had built a successful family business, and we needed to maintain that. So that feeling I had at the movies? I buried that. I was fearful that if I expressed that desire to be an artist — in a very pragmatic family — that the idea would just be shut down. As an older person, now raising children of my own, [I know] that my grandmother was a strong supporter of the arts and that she was teaching my grandfather what art could be, but at the time that didn’t matter. I wasn’t equipped with the language to tell them that I wanted to be an artist — any kind of artist — and I wasn’t at all interested in what was important to them. But after School Daze, I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker.

So when did it become possible to make that change for yourself?

Young: When I was 18, I literally didn’t even know that Black people made films. It’s crazy. But I had no examples; I had no reference. And that makes me a little emotional … because I’m happy that people of that age today can see some examples, but I had nobody other than Spike Lee, and later John Singleton, who were telling excellent stories in a visual, artful way. [Those filmmakers] never discounted the importance of good cinematography that could express the visual depth of the Black experience in America. And I can reflect on the sense of responsibility it took to do that.

I use Spike Lee and John Singleton as examples because they were the only two Black filmmakers I knew of at the time. It wasn’t until I got to Howard University that I discovered that there were people — like my teacher Haile Gerima — who knew more than I did. Then I understood that there had been a long tradition of Black filmmakers in America, and that that knowledge had to be passed on to young people, especially young people of color.

In college, I saw the films of Oscar Micheaux, Bill Greaves, Kathleen Collins, Charles Burnett, Julie Dash and Haile Gerima. That was world-changing for me — not just that they made movies, but that they made movies that were individual to them.

But I also want to be clear that my existence as a filmmaker was totally enabled by my two sisters. Even when it was just something in my imagination, they allowed me to go there. But that also meant — for my particular 18-year-old brain, that lizard brain — I had to let my family go for a while. I had to move away and go to college — with the encouragement of my sisters — to find a new family. The people I found were not my blood family, but my art-making family, and I found them at Howard. There are too many to name, but the person who pulled us in was Mr. Haile Gerima.

What I had to do was supplement the strong, very race-first, present, pragmatic voice of my grandfather, Mr. Woodford Porter, with another, similar strong voice — that of Mr. Haile Gerima. I needed that nurturing wisdom in filmmaking, which I could not get from my family, from somebody who would validate what I wanted to claim. I wanted to be an artist, and I needed somebody to guide me with that grandfatherly pragmatism — but [with] a free spirit. I needed somebody to say, “You are going to be an artist; you are going to make films.” Once I met him, I was able to claim that bag and pursue this art form in a way that was responsive and responsible to my community — specifically, the Black community. The African Diasporic community. That was key.