Batman Begins: The Bat Takes Wing

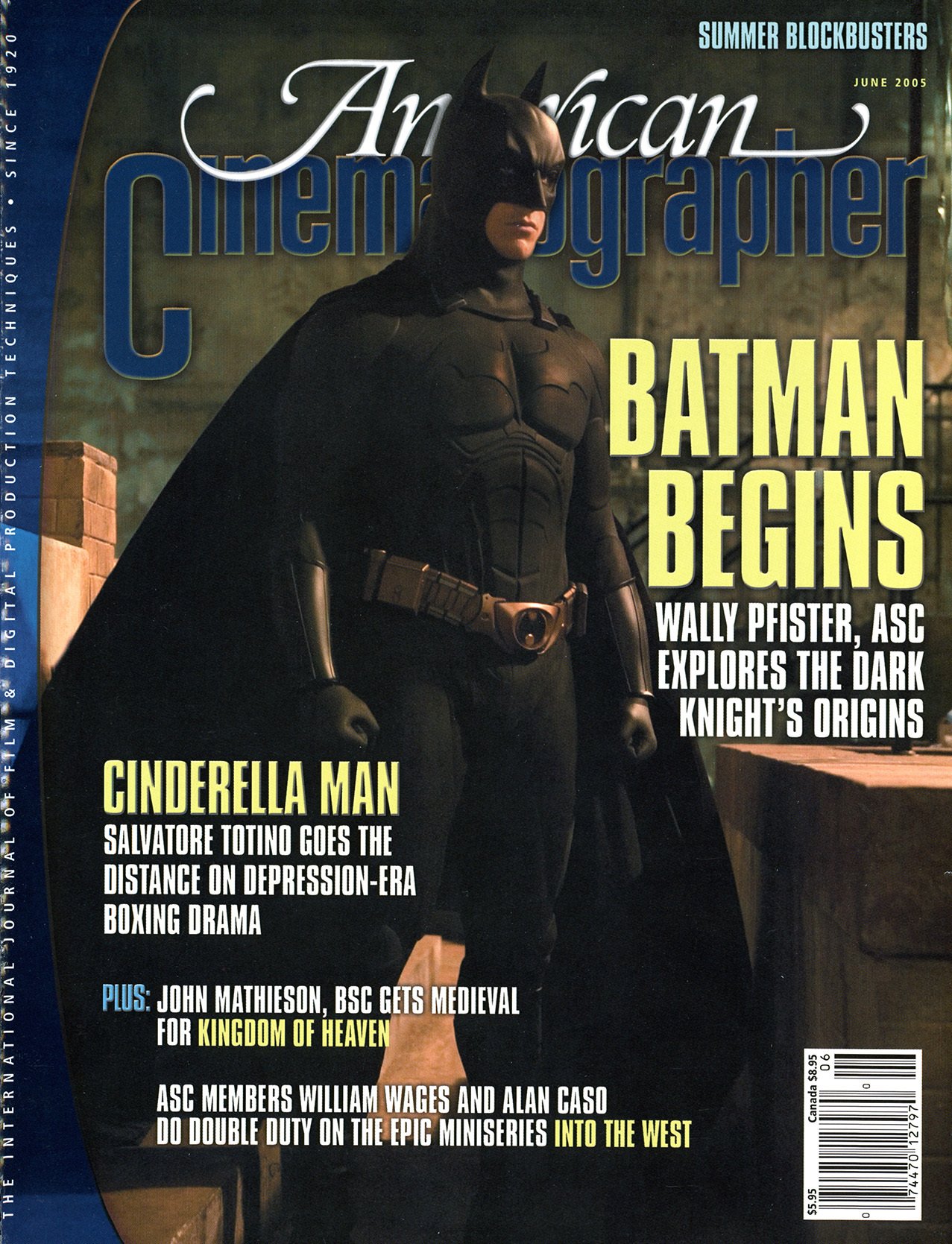

Wally Pfister, ASC helps director Christopher Nolan envision the Dark Knight’s “origin story.”

ASC. "We had Steve Adelson handholding a camera and tracking down with Batman. We tracked parallel to him, and we also had cameras at the top and bottom of the stairwell to get those angles.”

Unit photography by David James, SMPSP

Photos courtesy of Warner Bros.

Director of photography Wally Pfister, ASC is the first to admit he’s not a Batman aficionado, but he does have a fond connection to Gotham City’s brooding, crime-fighting vigilante. “I was a huge fan of the Sixties television show when I was a kid,” he enthuses. “My dad worked for ABC, and he used to come home with armfuls of Batman souvenirs — publicity photos, utility belts, a Batman projector that could beam a bat onto the wall, all kinds of stuff.”

Memories of this Bat-swag began swirling in Pfister’s mind when he learned that director Christopher Nolan, his collaborator on Memento (see AC April ’01) and Insomnia (AC May ’02), would take the helm on Batman Begins. “Chris said he wanted to tell the story in a way it hadn’t been done before; he wanted to dive not only into the origins of Batman, but also into the fact that he’s a superhero who doesn’t have superhuman powers. He’s a normal man — if you consider a billionaire to be normal — whose only special attributes are his intelligence, resourcefulness, fantastic physical condition and fighting abilities.”

After Nolan signed on to direct the film and co-write the screenplay (with David S. Goyer), Pfister paid a visit to the director’s Hollywood home, located not far from Bronson Caves, which famously served as the Batcave entrance on the TV series. There, he found Nolan and production designer Nathan Crowley, another veteran of Insomnia, already hard at work — or, perhaps more accurately, at play. Pfister recalls, “The two of them had assembled all of these materials in Chris’ two-car garage. It was like a kid’s workshop in there — the walls were covered with research, and Nathan had been building models for a brand-new Batmobile from toy car, airplane and rocket kits. What’s extraordinary is that if you look at the early model of the Batmobile that Nathan and Chris assembled, it’s very close to the final versions our mechanical-effects expert, Chris Corbould, and auto designer Andy Smith eventually built for the movie. Chris [Nolan] has a passion for every little detail, so from the beginning he was instrumental in every single design concept for the movie, from the bolts that hold the wheels on the Batmobile to the curves and lines of Batman’s cowl.”

“Chris wanted the film’s visuals to come from a very real place. He felt the settings should reflect the psychological underpinnings of a dark character who’s driven by tragedy.”

— Wally Pfister, ASC

Pfister brought an equally obsessive focus to his own work on the picture, which is designed to reinvent a Warner Bros. franchise that includes four previous films: Batman, Batman Returns, Batman Forever and Batman & Robin. True to its title, Batman Begins explores the character’s origins, as Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) transforms himself into the Caped Crusader to stem the tide of crime and corruption in Gotham City.

Pfister read the script in October 2003 after flying to London, where most of the production was based, for some initial discussions with Nolan. Interestingly, their talks began to touch on another superhero: the Man of Steel. “One of the things Chris and I discussed was how much we liked Richard Donner’s Superman,” says the cinematographer. “In general, I’m not a big fan of superhero movies based on comic books. I enjoyed the first Batman movie, and I also liked the way the X-Men movies looked. But to me, Superman [shot by Geoffrey Unsworth, BSC] was even more inspiring as a narrative. I thought it was cohesive and well crafted, and Chris and I both felt it really succeeded in putting a superhero onscreen in an effective way. One reason Superman works is that it has a strong story structure, and I felt the same way about the script for Batman Begins.”

Nolan adds that his take on Batman is a considerable departure from the stylized, baroque approach director Tim Burton adopted in his 1989 movie Batman. “Tim Burton’s Batman came from a very visionary and idiosyncratic view of the character,” he muses. “It’s a pretty fascinating movie, and it has its place in movie history. But they created an environment for Batman that was as exotic and extraordinary as Batman himself. That worked very well, but Batman has never had a film that portrayed him as an extraordinary figure [amid] a relatively ordinary and recognizable world. That was the thrill I’ve been seeking — the thrill of being amazed and of seeing the ordinary citizens of Gotham be as amazed about Batman as we are.”

“Chris wanted the film’s visuals to come from a very real place,” Pfister elaborates. “He felt the settings should reflect the psychological underpinnings of a dark character who’s driven by tragedy in his life. With that goal in mind, we tried to create a unique urban environment, something much different than what appears in the other Batman films.”

None of these goals would be simple to achieve, however. “I knew I would be confronting some big logistical challenges,” says Pfister. “All of a sudden, the film began to feel really huge.”

Because of the production’s size, Pfister knew he would need a lengthy prep period. Fortunately, the production obliged him, and he began working in November 2003, after moving his family to England. “I thought a reasonable amount of prep time would be 12 to 14 weeks, and because the start date was pushed two weeks, I actually ended up with 16 weeks, which was a bit more than I really needed,” says Pfister. “Within that time frame, I thought it was important to see the early stages of the design work. That’s a period that directors of photography often miss out on, because we sometimes get called in a little late. Fortunately, Chris realized the importance of having me involved.”

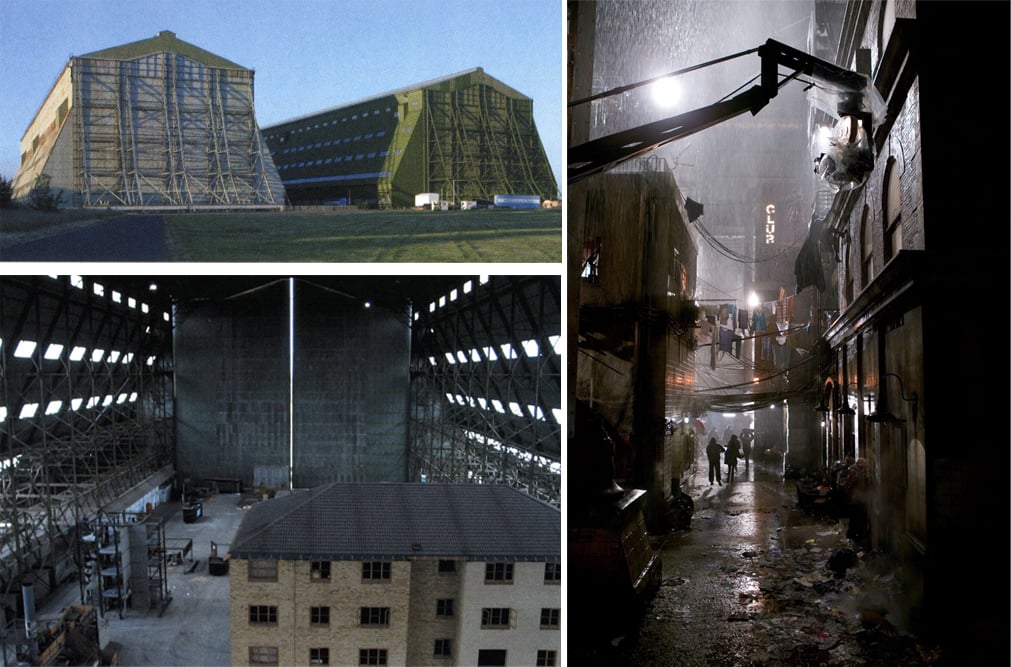

The production occupied several soundstages at Shepperton Studios, where Crowley’s sets included key Wayne Manor interiors, the Batcave, and a Himalayan monastery where Wayne receives martial-arts training. Even larger, however, was the set for Gotham City, which was built at a facility called Cardington. Located 90 minutes northwest of London, Cardington offered two enormous, adjacent blimp hangars that had been built in 1917. Both were still being used for aircraft, but one was deemed too decrepit for the production’s purposes. The hangar the filmmakers chose was 800' long, 500' wide and 200' high — plenty of space in which to create an impressive cityscape. “The doors at one end of the hangar are so large it takes 20 minutes to open them,” marvels Pfister. “It even has its own atmosphere — you can get clouds in there!”

“In recent years, there’s been a trend on big films for some of the more interesting setpieces to be split off and given to another director. I can’t really work that way.”

— Christopher Nolan

The hangar and the show’s other filming sites required considerable pre-rigging as the sets were being built. Gaffer Perry Evans supervised this work, as well as the construction of two 130'-high catwalks in Cardington, on which the crew could position large sources rented from Lee Lighting (which handled all of the production’s lighting needs). “I wanted to test my crew to see how fast they could rig things, because it was not my regular crew,” Pfister notes. “In England they have what’s called sales leaseback, which is basically a tax credit, and every American you bring in is an amount that’s subtracted from the tax credit, so the studio usually wants to minimize the number of Americans brought in. Therefore, I was only able to use my regular gaffer, Cory Geryak, when we were shooting a big chase scene in Chicago. I knew that seeing how fast the English crew worked would allow me to make informed recommendations to Chris once shooting began. Fortunately, Perry and his crew were fantastic.”

While the crew pre-rigged, Pfister conducted 12 days of tests, evaluating a series of technical matters that included gel colors, makeup, smoke and fog, visual effects, camera-motion systems, tracking vehicles, and, of course, Batman’s cape and cowl.

He and Nolan prefer to work in the anamorphic 2.40:1 format, so he also spent some time assessing various widescreen lenses. “I wanted to examine the three sets of Panavision anamorphics: the Primos, the C-Series and the E-Series. In the end, I primarily used E-Series lenses, but I used some C-Series lenses for handheld work. I used E-Series lenses on Memento and Insomnia and think they’re terrific-looking. I like the way the flares look, they’re more lightweight than Primos, and they’re very sharp. I mixed Es and Cs quite a bit on Batman Begins, though. If we found a 40mm lens that looked better in the C-Series than in the E, we’d use it. We shot almost all of Memento and Insomnia on a 75mm E-Series lens, but on Batman we used a wide variety. We shot quite a bit wider than we had previously to better establish the geography and because we were tracking action with vehicles. Chris preferred using wider lenses closer to the action and characters.”

Pfister therefore shot a lot of footage with 35mm and 40mm lenses, but his workhorse was the 50mm. For close-ups, he often used a 75mm but occasionally employed a 100mm or a 135mm. “Longer lenses weren’t really feasible once we got to scenes involving smoke and fog, so we did most of those close-ups with the 50mm and 75mm.

“You don’t want to get those wrong on a Batman movie!”

— Wally Pfister, ASC

“I tried to maintain a stop of T2.8.5 inside Cardington, though I opened up more at times,” he continues. “In Chicago I was probably closer to T2.8, and I also had to push the film. We used a lot of ambient city light in Chicago, so I needed a bit more stop. The other sets were between a T2.8 and a T4; I was generally at T4 for day-interior work. When you open up to T2.8, there’s a huge difference in the sharpness. Shooting at T4 can really give the focus puller a fighting chance, because focus becomes pretty critical when you’re shooting with a 135mm lens 5 feet from the action at T2.8. I have to say, first AC Clive Mackey did a nice job of handling some very challenging focus situations.”

Pfister’s main cameras were a Panaflex Platinum and two Panaflex Millennium XLs. “I always had one built in a standard studio configuration, one in a Steadicam configuration, and one as a handheld camera. Occasionally we brought in a PanArri 435 for high-speed work. For the Batmobile chase in Chicago, we also carried a bunch of Eyemos and smaller cameras.” Pfister operated the A-camera himself, even on second-unit footage, which he and Nolan supervised. Vancouver-based operator Steve Adelson handled the B-camera and Steadicam work.

Addressing the unusual step of eschewing a second unit on such a large project, Nolan offers, “In recent years, there’s been a trend on big films for some of the more interesting setpieces to be split off and given to another director. I can’t really work that way. After all, the reason I wanted to do this film is that I wanted to shoot the car chase, and I wanted to shoot Batman. I don’t really want to give those things to someone else; as a director, I have to believe that there’s some value in my brain being behind every scene on the set, not just in the edit suite. If you’re viewing the overall film in visual terms, it’s very hard to split off the shots that you think are unimportant or less than deserving of first-unit treatment. One of the things Wally and I do is to shoot all the inserts as we go along. Some people raise their eyebrows at that, but the truth is, that insert, that close-up of the hand, is going to end up on the same screen as the close-up of the actor, and it’s going to occupy the same space in the audience’s field of vision. Those insert shots are also about storytelling — otherwise, you wouldn’t need them.”

In considering his “stock options” during prep, Pfister quickly settled on Kodak Vision2 500T 5218 and Vision 250D 5246. “I knew I was going to shoot most of the picture on 5218, and I also knew I wanted to push the stock. The more I examined the Chicago portion of the shoot, the more I wanted to use a lot of available light there, so I decided to push the film one stop for that entire sequence. I did tests to see whether Chris or the visual-effects team had any issues with the grain, and I found that 5218, when pushed in anamorphic, is extraordinary — it really looks good. I tried rating it at ISO 400, and I liked that better than ISO 500, so when I wasn’t pushing it I overrated it to get a deeper negative and to enrich the blacks when they were printed down.

“I also did a number of bluescreen and greenscreen tests for the visual-effects team. 5218’s grain structure is exceptional, a huge improvement over [Vision 500T] 5279. I never would’ve considered pushing 79 a full stop on a picture like this, but the 18 has such a clean grain, particularly in anamorphic, that everything worked out well.

“I used 5246 for day work, which comprises about 15 percent of the picture,” he continues. “I tested 5218 for day work to see if I could get something interesting, but I ended up choosing 46, which is what I usually use for day work. In fact, a lot of the tests on this show involved me trying new things and then coming back to what I usually do! I rated 46 normally, at ISO 250.”

Pfister and Nolan decided early on not to do a digital intermediate (DI) on the show. “We’re both a bit leery of all the hype about DIs,” the cinematographer reveals. “I’d done a little DI work on The Italian Job [AC June ’03] and was not as happy as I hoped I’d be. I found the images picked up a little digital grain when they went through the process. Chris was also concerned about having too many hands on the material, and about how much time a DI might take. We both concluded that I could give Chris the look he wanted through the traditional photochemical process. I had a great experience with [Technicolor London] color timer Peter Hunt, and lab supervisor John Ensby, and Panavision U.K. rep Hugh Whittaker. The result is a print that is so rich in color and density that we’re thrilled we decided to go in this direction. Aside from pushing 5218, everything was developed and printed normally. The film will also be released in Imax, and the initial Imax tests were stunning.”

Following all of this prep work, Pfister felt confident that he was ready to head into production on the biggest picture of his career. During two interviews with AC, he outlined his approach to key sets and situations.

![Wayne and his loyal butler, Alfred (Michael Caine), return to Wayne Manor, where they find the furniture and paintings shrouded in white, ghostlike sheets. To illuminate this scene, Pfister positioned a Lightning Strikes 100K SoftSun outside the window. “I first saw the SoftSun while visiting Rodrigo Prieto [ASC, AMC] on the set of Alexander, which was shooting [some scenes] at Shepperton Studios,” Pfister reveals. “I was impressed with the big, punchy source it created, and I made a note of it in my mind.”](/imager/uploads/93190/Batman-Begins-Alfred-and-Bruce_6c0c164bd2b597ee32b68b8b5755bd2e.jpg)

Before Wayne becomes Batman, he enjoys a privileged upbringing at “stately Wayne Manor” as the son of extremely wealthy parents. Then the brutal murders of his mother and father leave him a troubled, embittered orphan with ample motivation for revenge. To convey the full emotional impact of this loss, the filmmakers wanted to render scenes of Wayne’s youth as “golden years” that held the promise of a bright future. Instead of using actual golden tones or a sepia look, which Pfister and Nolan deemed “too cliché,” Pfister played these scenes in soft light. “The light on Bruce as a child is very gentle, with a little more fill than I use in the rest of the movie. This softer, more pleasing light emphasizes that those childhood days were when he was happiest and when Gotham was in its prime. His parents were alive, the economy was good, the trains were running, and crime was low.”

Things take an ominous turn for young Wayne when he tumbles into a well on his property and is engulfed by a swarm of bats — an incident that scars his psyche and indirectly sets up the eventual murders of his parents. One evening, Mr. and Mrs. Wayne take their son out to see an opera, but the show features flying creatures that remind young Bruce of his traumatic encounter with the bats. He begs his parents to leave the theater, and when they do, they are slain by a mugger.

After this incident, Wayne’s life is never the same, and the tragic turn of events is reflected in the presentation of Wayne Manor. Exterior shots of the mansion were captured at an estate called Mentmore House, located in Hertfordshire. Key interiors were shot on stage at Shepperton. “When Bruce is a child, Wayne Manor is a big, wonderful place that he embraces,” Pfister notes. “Years later, when he returns to the mansion with Alfred [Michael Caine], the place has an eerie, uninviting feel. Nathan and Chris decided to cover all of the furniture and paintings with long, ghostlike sheets, and I decided to make the lighting very monochromatic, very sterile, especially during the scene in which Bruce and Alfred walk up the main staircase. I had a Lighting Strikes 100K SoftSun coming through the windows at Mentmore as the two men climbed the stairs.”

“The SoftSun was a really good choice for that location,” adds Evans. “I’m always a bit scared to use one large source, because if it breaks down, you’re stuck. You can always have a spare 18K on hand, but you can’t just ask for a spare SoftSun! But the SoftSun performed well for us. It’s small enough that we could rig it onto a fairly small crane, which was very helpful because access to the mansion was quite limited. The light from that unit bounced off the white environment and created a very pleasing look. The only other fixture we used for that scene was a 1.2K HMI to create a bit of fill.”

Pfister credits Evans for bringing his English ingenuity to bear on a later scene at Wayne Manor involving a birthday party for the adult Bruce. The sequence takes place in a large, open atrium, where the cinematographer wanted to soften some of his larger sources. “The room was about 50 feet square, and I had to light up the entire space because Chris wanted a lot of flexibility in terms of what we could see there,” says Pfister. “We brought in four lighting balloons — two tungsten and two HMI — to provide general fill, and they were probably about two stops under key. For the key, I used the balcony in that space to position 5Ks, 10Ks and Mini-Brutes to create edgelight. I wanted to soften that edgelight, though, so Perry and his guys clamped together several 4-by-8 frames of diffusion that we could either hang from the ceiling or position on stands. One great way to soften a light is to place the diffusion a great distance from the source. This atrium was so large that we could have a 10K up in the balcony aimed through a piece of diffusion hanging from ropes in the middle of the space, 30 feet from the source. We’d just lower our diffusion down until it was in front of the light.” Adds Evans, “In England, we bolt together those 4-by-8 frames all the time, but Wally had never seen that technique before, and he thought it was brilliant. You can just keep adding as many frames as you need to the whole arrangement. At one point, I think we had about six of them tethered up in the air.”

To add a finishing touch to the scene, Pfister used China balls lamped with 250-watt bulbs to provide eyelights. “When I operated for Philippe Rousselot [ASC, AFC] on Instinct, I watched him light tons of stuff with China balls,” he recalls. “I don’t use them very often, but they’re very handy for certain situations. In this case, we were far enough from the walls that they wouldn’t illuminate the walls as we brought them in. We sometimes dimmed them down or put them behind a frame of diffusion.”

“What appealed to me about Iceland, as opposed to other mountainous locations in Europe, was the extremity of the scenery. It’s utterly bleak, with volcanic rock and glaciers. It’s so stark that it says something very extraordinary about Bruce Wayne’s [psychological state].”

— Christopher Nolan

After becoming disillusioned by Gotham’s downward spiral, Wayne journeys to a remote monastery in the Himalayas, where he meets a martial-arts mentor, Henri Ducard (Liam Neeson), and a ninja contingent headed by the mysterious Ra’s al Ghul (Ken Watanabe). Some shots for these scenes were filmed on location in Iceland, while others were filmed onstage at Shepperton. “Chris and Nathan scouted Iceland before I came onto the production,” says Pfister. “A lot of the picture takes place at night, so Chris was looking for a location where he could get some spectacular daytime imagery.”

Nolan offers, “What appealed to me about Iceland, as opposed to other mountainous locations in Europe, was the extremity of the scenery. It’s utterly bleak, with volcanic rock and glaciers. It’s so stark that it says something very extraordinary about Bruce Wayne’s [psychological state] and the place he’s at in his life. The location needed to have that almost surreal extremity.”

Pfister and his crew took full advantage of Iceland’s photographic possibilities. "We did some helicopter photography there with my regular aerial cinematographer, Hans Bjerno, and we also staged a wonderful swordfight between Wayne and Ducard on real ice,” the cinematographer details. “I went out onto the ice with a handheld camera, and we put Steve Adelson on a Western dolly with the Steadicam. We all just kind of slid around for a day!”

The exterior of the monastery comprised several different elements: a real exterior in Iceland, which included several small buildings; a miniature used to enhance the scale of the place; and an exterior set built in Cardington that would be destroyed in a spectacular explosion. In addition, the production built two monastery interiors in Shepperton’s Stage C: a candlelit “Throne Room” where Wayne first meets Ducard, and an open, three-story courtyard where Wayne learns martial arts.

Crowley initially designed the Throne Room to have somewhat solid walls and a ceiling, but Pfister worked with him to retool the space to allow dappled “daylight” to filter through various openings. “We covered the open areas in the ceiling with our 4-by-8 frames, which we could move around,” explains Pfister. “We put pieces of diffusion over some of the holes but left others open to create random patterns of light.” Additional light in the Throne Room was motivated by lanterns and candles. “I wanted to find a careful balance in terms of both color and density while maintaining a very dark look,” says the cinematographer. “I also used smoke there because it was very well motivated by the lanterns. I don’t usually use smoke, and when I do, I like to have a reason for it.”

In the courtyard, Pfister wanted to create the feel of soft, ambient daylight to match the look that had been photographed in Iceland. Again, he worked on the design with Crowley to create platforms around the uppermost balcony and flexible openings in the sides to let in the light. A total of 16 quarter Wendy Lights were positioned on the platform, four to each side. “I wanted to maintain a bit of edgelight at one or two stops over key, and I kept my fill light about two stops under,” he says. “Most of the time, three sides of our [grid] were turned off. Depending on which direction we were going to look, we could maintain a soft backlight by just turning off one set of lights and turning on the next set. We also had frames of diffusion hanging from the grid that we could lower down to soften our sources as we tightened up the shots.” Additional lighting for the courtyard was provided by four 20Ks positioned on the platform, and 25-30 2K Blondes that were used to send light through openings in the walls. Evans also talked Pfister into installing some space lights overhead. “Wally was a bit loath to use those at first, but we never used all of them at once,” he says. “We could turn on some of them to provide extra backlight in whatever direction we were facing.”

One spectacular sequence follows the monastery explosion, which sends Wayne and Ducard hurtling down an icy slope toward a massive chasm. Ducard actually slides over the edge but is saved by Wayne, who grabs his arm at the last second. “Chris wanted to shoot that sequence as practically as possible, and he put the onus on Paul Jennings, the English stunt coordinator, and Chris Corbould, our special-effects coordinator,” says Pfister. “He wanted to know if we could have two stuntmen slide down to the edge of the cliff, which had a 300-foot drop at the end of it. Chris also asked me to take the camera out over the edge with them as they slipped over it. He wanted to go from looking horizontally to looking straight down into the abyss.”

“By combining all of this footage, I think we managed to create a slide and fall that looks a lot more credible than the typical greenscreen stuff you usually see with such a stunt.”

— Wally Pfister, ASC

Stuntmen Buster Reeves and Mark Mottram (doubling for Bale and Neeson, respectively) performed this death-defying feat after being attached to safety cables connected to various pick-points on the slope. The sequence was ultimately assembled in several sections, however. Shots of the two men heading toward and off the cliff edge were captured in a wide shot made from a dolly and a telescoping shot made with a 30' Technocrane. The crew then filmed some medium shots of Bale and Neeson sliding down a safer slope. Finally, close-up work of the stars was shot on a fake partial slope that ran about 60' and ended with a greenscreen that would allow a shot of the abyss to be composited in during post. “By combining all of this footage, I think we managed to create a slide and fall that looks a lot more credible than the typical greenscreen stuff you usually see with such a stunt,” Pfister maintains. “We did two key shots for real that will help sell it for the audience: the side-angle profile of our two stuntmen going off the cliff, and the Technocrane shot that follows them right over the lip. The stuntmen had to shield their faces from the camera, but we were right with them as they went over."

After Wayne survives his Himalayan trials, he returns to Gotham City as a hardened fighting machine bent on restoring a semblance of order. In describing the look he sought for Wayne’s hometown, Nolan says, “Gotham was about creating a sort of ‘New York on steroids,’ but we also incorporated elements of other major international cities — elevated freeways from Tokyo, slums from Hong Kong, and underground streets from Chicago. [One of our influences] was the extremity of the architectural repurposing that had once gone on in Kowloon [Hong Kong]. We had great photographic references of amazing, covered-in alleyways with pipes running up and down. Essentially, Gotham is a mix of all of the most interesting, oppressive and divisive architectural elements from the great modern cities.”

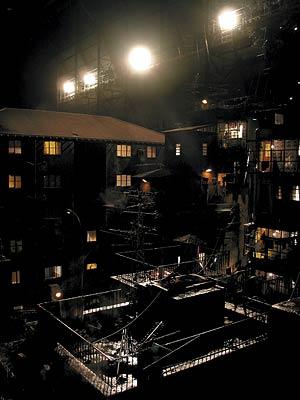

In building Gotham within the Cardington blimp hangar, Crowley and his crew incorporated some of the facility’s existing features, which included three buildings and an array of metal support beams. Pfister contributed ideas at the design phase so he could take full advantage of the space. “Very early on, Nathan built paper models of the city, and we sat there moving them around to figure out the ideal arrangement. I might say, ‘Moving these buildings a little bit that way will give us a long, clear line of sight all the way down the street; I can put some light in the background and we’ll have the most depth possible.’ We also discussed what I needed inside the buildings. At first, the production didn’t want to make some of the buildings structural because it was very expensive, but I really argued for it because we had to get electricians inside and on top of them. The studio eventually bit the bullet and paid to make those structures completely accessible. Nathan is a fantastic artist and a generous collaborator; he really helped us fight for what we needed to create a flexible lighting environment.”

“We wanted to avoid anything that would make the audience think ‘Backlot!’ Chris was very keen to make sure we didn’t photograph the same areas over and over again, because there’s a sort of subliminal recognition on the viewer’s part that can serve to shrink the picture’s scale.”

— Wally Pfister, ASC

To make Gotham appear more realistic, Pfister lit all of its buildings from within. “Ninety percent of city lighting is about the lighting within buildings rather than exterior light, so we placed a variety of lights in all of our Gotham structures.” Installing these units was a task that fell to Evans and his crew. “We used a mix of fixtures behind windows: 2Ks, Blondes, Pups, Redheads and 650s,” the gaffer details. “Some of the units were clean, but Wally also picked out three or four different gel colors to use: soft yellow, CTO, CTB and 1⁄4 or 1⁄2 Plus Greens.” On the roofs of each building, Evans also stored larger units — 5Ks, 10Ks, Maxi-Brutes and others — that could be called into service at a moment’s notice. Two 200' cranes equipped with Wendy Lights were positioned at ground level, but limited floor access meant that the filmmakers had to find another way to create most of their foundational lighting.

The solution was the construction of the aforementioned 130'-high catwalks, which ran the length of the hangar on both sides and allowed the crew to install two rows of large, varied sources. The catwalks were an expensive undertaking, but Pfister and Evans agree that they increased efficiency dramatically. Evans explains, “We alternated different sources along each side of the hangar: quarter Wendys for ambience, half Dinos to pick out certain architectural highlights, and 20K Fresnels. Here and there we substituted Maxis for some of the half Dinos. We had at least 10 of each type of light up there. The whole setup was powered by four megawatt generators, and we ran 40 miles of cable.” Adds Pfister, “Once the foundational sources were in place, we also positioned some lights on the ground. To add fill to the actors’ faces, I might aim a 2K Zip light through a frame of 216 diffusion. My approach was simple: light the background to create the overall environment, and then go in with a small light to pick up the faces. Many scenes worked that way.

“My goal at Cardington was to create an interesting mix of colors that would be true to a real urban environment,” he adds. “It was a matter of choosing the two primary urban colors: an orange, sodium-vapor look and a blue-green, mercury-vapor look. If you fly over any major city, those are the two defining colors in the streetlights below you. They complement each other, and they allowed me to add some fun, interesting hues that were well grounded in reality. We used 1⁄2 Straw gels for our orange-yellow foundation, and 1⁄4 Blue and 1⁄2 Green gels for the blue-green look. We even assembled about 400 practical street fixtures and put them up all over the hangar.”

Pfister also addressed one of Nolan’s primary concerns by changing up the look of different streets if they had to be reused. “We wanted to avoid anything that would make the audience think ‘Backlot!’ Chris was very keen to make sure we didn’t photograph the same areas over and over again, because there’s a sort of subliminal recognition on the viewer’s part that can serve to shrink the picture’s scale. We made certain set details stand out, but we were very careful to disguise things if we did reuse a specific area. For example, if we used one street for a given scene, we’d make it look completely different for another scene by changing a bunch of the neon signs.”

Another major Gotham setting, of course, is the Batcave. In Batman Begins, we see Wayne’s famous underground hideout during its formative phase, before it becomes fully equipped with sophisticated equipment. The cavernous space consists mainly of sloping rock walls, a river and two waterfalls, all located beneath the visible foundation of Wayne Manor. Crowley and his crew built the massive set on Shepperton’s largest soundstage. According to Evans, “The only sources of light in the Batcave were the cracks in the ground above it and the openings behind the waterfalls. We lit the set with a variety of units; space lights hung from an overhead grid; 10Ks and 20Ks that were also rigged in the gantry; a row of 2K Blondes positioned at floor level near the lift shaft; and several 20Ks that we used to backlight the waterfalls, including a Molebeam behind the one at the cave’s main entrance. On the ground, Wally kept things very low-key, right at the bottom end of the exposure meter — I thought his approach was very ballsy!” (Pfister responds with a laugh, “When things get that dark, I tap on my light meter and look at it as if it’s broken.”)

The filmmakers made the most of the spectacular setting, which was quite expensive to build. “I wanted Chris to show me the precise spot where Wayne would first enter the cave,” Pfister says. “I spent an entire Saturday pre-lighting the first shot we did there, which took place on the following Monday; I didn’t want Chris standing around for five hours while we lit up a cave, so I roughed in all the lighting for the major directions. I relied on this notion of an edgelight coming through and across the cave. We added raking light from the side and some frontal light on the rock so that you could see the texture, color and moisture. We had a certain amount of atmosphere in there as well, because the waterfalls added a mist to the air. It wound up being a very realistic look.”

One piece of high-tech ingenuity that does appear in the film is the Batmobile, which is seen in several phases of its development. In the initial phase, it is a camouflage-colored prototype that Wayne Industries’ technical wizard, Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman), is developing for the military. When Wayne takes a shine to the vehicle, however, it is refined and perfected in his preferred color, matte black.

Five working Batmobiles were built for the show, and the vehicle’s big moment arrives during the film’s climax, a wild car chase that begins on the Cardington set and continues on real streets in Chicago, including Lower Wacker Drive and a stretch of freeway north of the city. Tying together the studio sets with actual roadways became a primary challenge of the sequence. “When you look down the street in the real city, you’re going to see down 20 or 30 city blocks, whereas at Cardington we were lucky to see two or three blocks,” Pfister points out. “We had to pull out a few tricks to integrate those two looks, and one of the keys was finding a foundational color. That was my standard city night look, a 1⁄2 CTS color. It was a good conceptual match with the yellow sodium-vapor lights in the tunnel of Lower Wacker. I thought I could light the sequence minimally if we were looking in the right direction; Chris liked the idea of being able to shoot two-mile stretches of that road without running out of lit set.”

According to Geryak, lighting for this part of the sequence consisted primarily of existing fixtures in the tunnel of Lower Wacker, although supplemental units were used to highlight areas where specific pieces of action would occur. “Fortunately, Lower Wacker had been redone recently, so there was enough of a light level in the tunnel to get some exposure,” Geryak says. “We rigged some additional units, including lots of Par cans, to illuminate the spots where specific stunts would happen. The Pars were gelled with 1⁄2 or Full Straw to match the existing fixtures’ sodium-vapor look, and we added some Opal diffusion just to spread them out a bit. Once we were out of Lower Wacker and on surface streets, we did a lot more lighting with BeBee lights and other units. On the freeway, we hung Par cans on the streetlights to punch those up a bit, and the police helicopter’s Xenon searchlight lit up the Batmobile for a good chunk of the sequence.” He notes that his crew’s biggest lighting setup was atop a parking structure where Batman finally manages to escape his pursuers.

During the nearly 10-minute chase sequence, the Batmobile duels no fewer than five police cars and a helicopter, and the filmmakers tracked the action from several vehicles. Borrowing an approach he had used on The Italian Job, Pfister had the top of a Mercedes ML-55 AMG rigged with a Lev Head mounted on an Ultimate Arm, which could swing completely around in 360 degrees as it tracked the Batmobile. (Both the head and arm were designed by Lev Yevstratov and provided by Adventure Equipment; the cars and additional rigging were provided by Performance Filmworks.) To capture profile shots of Batman’s car, the production employed a motorcycle with an attached sidecar equipped with a Libra IV Head. “Nick Phillips, the inventor of the Libra head, was nice enough to act as our Libra tech in Chicago,” Pfister says. “George Cottle drove the Batmobile, and we also had a fantastic team operating the Ultimate rig. Dean Bailey drove the tracking vehicle, George Peters operated the Ultimate Arm and Michael Fitzmaurice operated the Lev Head, and they all helped capture some of the most dynamic car footage I’ve ever seen. Chris was skeptical of the Ultimate Arm at first, but when I showed him what it could do, he was impressed. Soon he was asking me if we could just drive through stunts with it! We had several big stunt setpieces where the Batmobile blows past one cop car hitting another and then flipping over. Chris didn’t want to track with the Batmobile and then have everything come to a stop with five or six cameras covering the stunt in slow-motion. He wanted the chase scenes to be more integrated, to have more of a French Connection or Bullitt feel.”

Adds Nolan, “To me, the chases in those films were always rooted in this kind of great automotive reality, and I wanted ours to have that same kind of feel. We didn’t want anybody ever thinking that we’d done this chase with a digital Batmobile; we wanted the audience to be very aware of the reality of it. By using both the Lev Heads and hard mounts, we were able to shoot in one direction on the street and then shoot more even during the reset on the way back, a system that allowed us to build up a library of footage. Wally understands the way I need to cut these things together and the types of shots I need; he knows we can just kind of grab these things as we go, rather than doing one shot and then waiting for 50 cars to reverse back into position. We tried to set up a more fluid, modular system for shooting this type of car chase.”

Pfister and Nolan did their best to keep stress at bay during the long shoot by creating and maintaining a “comfort zone” around the camera. “One of the reasons Chris likes me to operate is that it shrinks down the whole process for him,” says Pfister. “We could be sitting on the set with 150 people and huge setups, but when the camera rolls, it’s just Chris sitting next to me with a little monitor, and the actors right there in front of us. His entire universe is in that 12-foot area, which brings the process down to a more personal level. Chris is not one to succumb to pressure, but this approach helps him to maintain that sense of coolness and control. There’s a great level of communication and trust between us.

“Of course, because we’re on such familiar terms, we do occasionally get into intense discussions,” he notes with a laugh. “But those discussions are always constructive. We’ll analyze everything down to the point where we’ve argued both sides so well that the scene is certain to get photographed in the best possible way.”

Anamorphic 2.40:1

Panaflex Platinum, Millennium XL; PanArri 435

E- and C-Series lenses

Kodak Vision2 500T 5218, Vision 250D 5246

Printed on Kodak Vision 2383