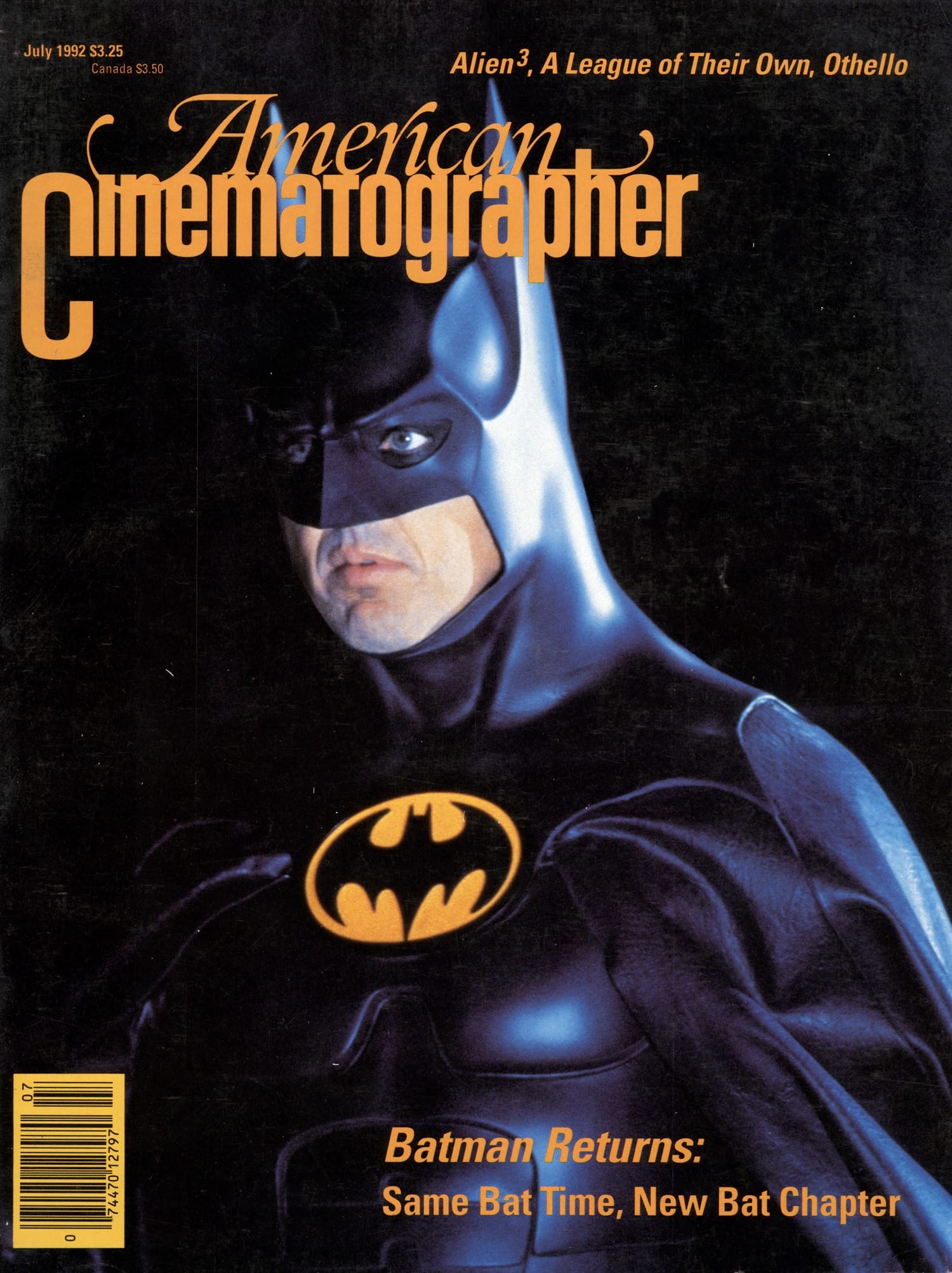

Back to Gotham: Batman Returns

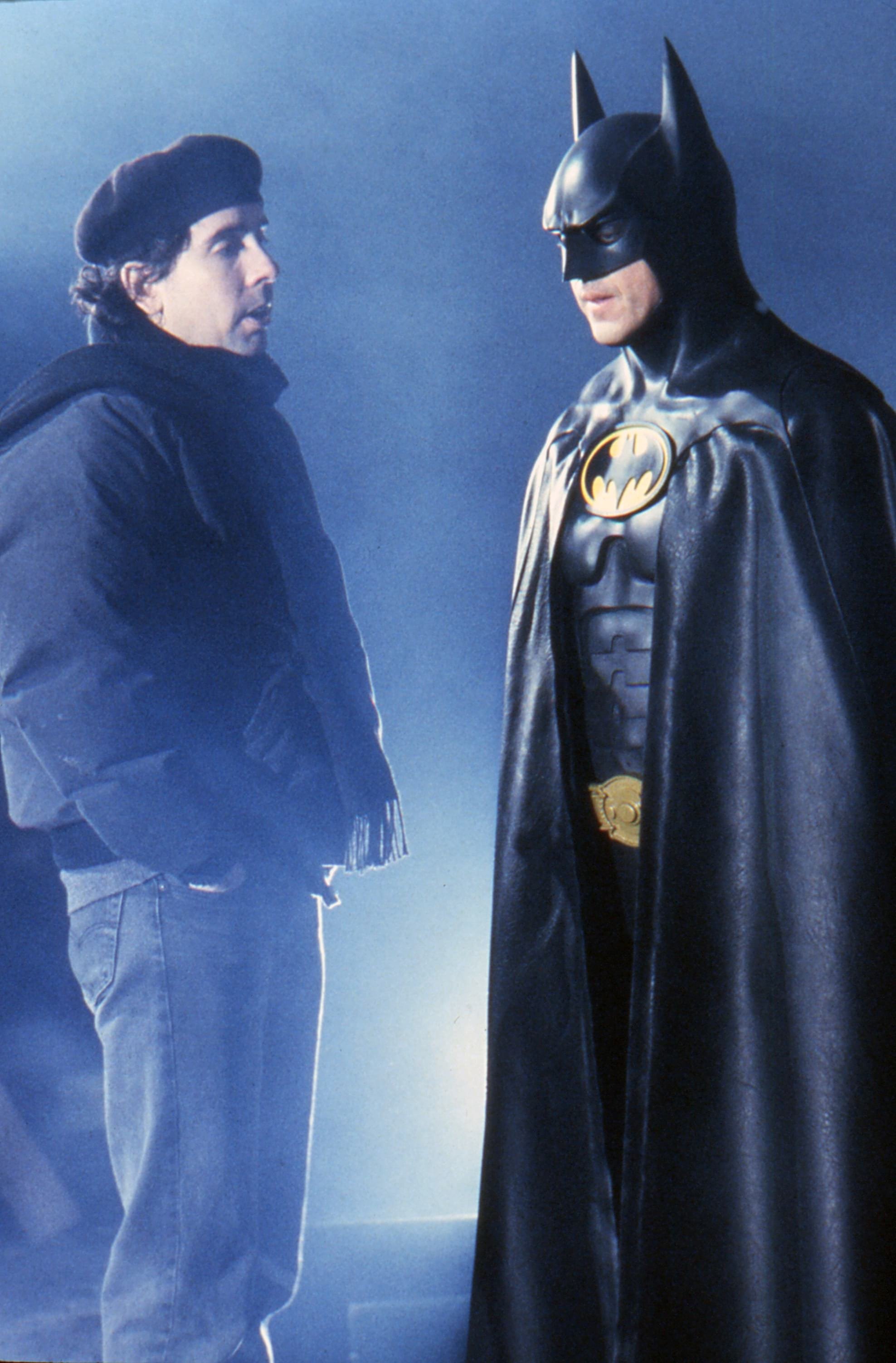

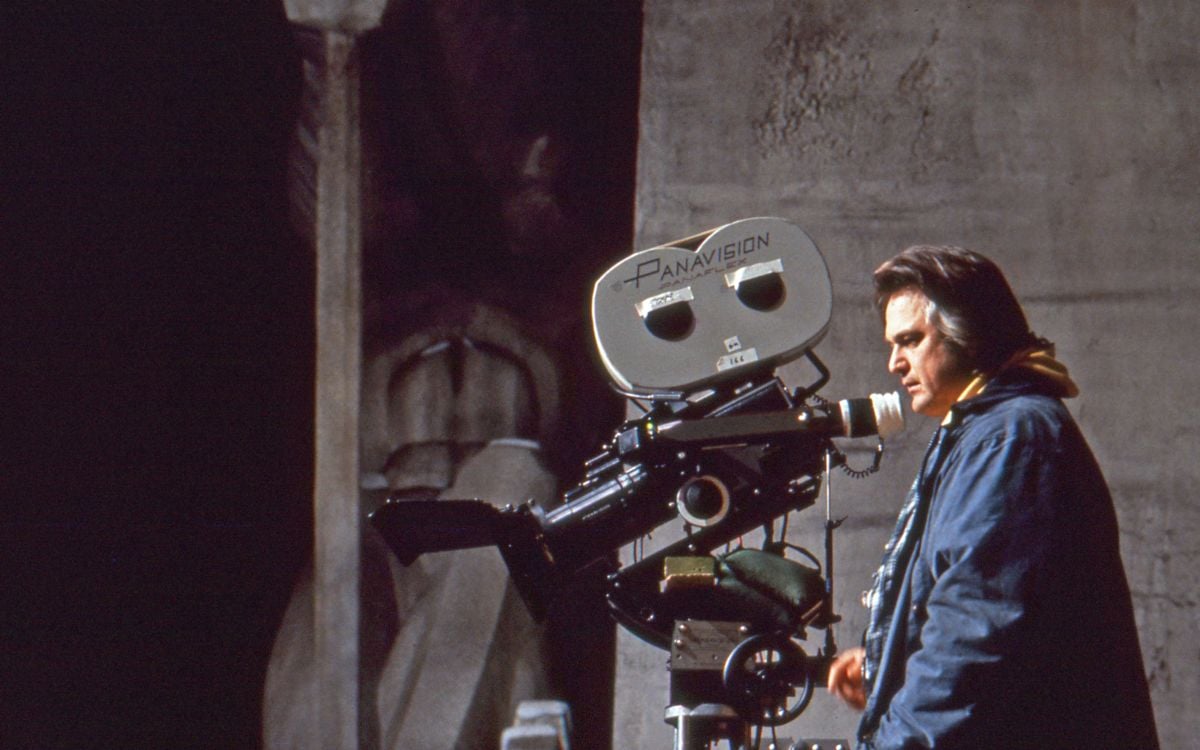

Tim Burton returns to Gotham City with a followup to his smash 1989 hit Batman, this time joined by cinematographer Stefan Czapsky.

Cinematographer Stefan Czapsky’s career would undoubtedly have taken off even if he'd never met Tim Burton. He has shot a handful of features in a broad range of styles, from the gritty nightmare realm of the cult favorite Vampire's Kiss, his first film, to the documentary realism of The Thin Blue Line. But after his remarkable job creating the rich fantasy landscape of Burton's magical Edward Scissorhands, the director asked Czapsky back to shoot what may be the key film of his blossoming career: Batman Returns. "This is the biggest film I've ever done," Czapsky admits, his New York accent contradicting the exoticism of his name. "It's a big movie."

It wasn't the size of the film that intimidated the burly cinematographer, but rather the tremendous success of the original Batman—the fifth highest grossing film of all time — and the resulting expectations of sequel-hungry studio execs and moviegoers. "Everyone recognizes that the Batman thing was a sociocultural phenomenon," Czapsky allows. "To try to repeat that tremendous success was pretty courageous on Tim's part. Fortunately, I felt no pressure to imitate the first movie. Tim never mentioned it to me. He doesn't like to talk that much anyhow and it would've been out of character for him to talk about the first movie. I never saw it in a theater; I was working all the time and had a certain resistance to seeing the mainstream blockbuster." He pauses, then laughs. "Actually, I think it had to do with jealousy, especially when I was working on things that were so far out of the spotlight!"

Czapsky soon learned that working in the spotlight has its share of troubles. He knew he was in for a difficult shoot when Burton and designer Bo Welch first showed him the models of the sets. "They were great," he recalls. "I would think, 'Are they really going to be able to build that in the set?!' I'm skilled at working in the full gamut of approaches they could take, so I was prepared and willing to alter how I approached lighting the sets; I didn't want to restrict the director."

Burton's approach to the material depends on a great deal of careful pre-planning before shooting and a certain amount of serendipity during principal photography. "Tim makes careful choices about the actors and he's fanatical about the design. Yet, for someone who cares about the look so much, he just sticks all of those things in there and lets them go by themselves!" Czapsky marvels. "It sometimes seems like a circus, but it's much more of a mystical thing for Tim in that he trusts that what will come out is going to be great. When you feel that, it makes you want to work hard."

Burton and Czapsky found shooting on Warner Bros.' Burbank soundstages very different from the "hands off" situation they enjoyed on the Florida location of Edward Scissorhands. "Batman was more like shooting in a goldfish bowl because we were on the lot and there were a lot of people watching us, even though it was a closed set," Czapsky recalls. At no time was this more true than when he began planning his lighting approach to the film's numerous oversized sets, which filled the studio soundstages to bursting. "They built the sets right up to the ceiling," Czapsky says. "If I was on a stage that was 65 feet high, the set walls went 65 feet up, so placement of the lights was a big issue. The studio people were worried about it from the moment we started to prep. They wanted to know what my plan was, if I had a plan and how I was going to do this! Most of my prep time had to do with checking out the sets and coming up with a plan."

Czapsky's plan, forced on him by the fact that the massive sets came right up to the permanents, was simple and straightforward. "I had to figure out some way to hang my lights from the permanent beams," he explains, "and the answer turned out to be a bunch of Trilite rock-and-roll trusses. These trusses were long metal pipes arranged in a triangle, so we just attached our lights to the pipe using steel fitting clamps. The weight limit of each truss was about 750 pounds, so I'd fly lightweight rock and-roll cans, baby juniors and a bunch of Mole Richardson 9-light maxilights on them and hang them in the mid-ground above the top of the frameline and our actors. I could lower or raise the truss on a chain motor, but they didn't always hang horizontally and sometimes the one at frame left would be higher or lower than the one at frame right. Once Tim blocked the scene, we'd usually have a couple hours to set up, so we'd quickly hang our trusses. Fortunately, I'd put together a great crew who were able to throw the equipment up and move it around quickly. Barry Lopez, my flyman, has done Broadway shows and is an expert at hanging stuff.

"The basic workforce unit was the Par bulb," Czapsky adds. "They were like big headlights and went into those maxis and the hundreds of rock-and-roll cans. Most of my lighting on Batman came from cans with spot, medium or flood bulbs in them; I almost always used a spot because I needed the throw when I was lighting from 60 to 70 feet up. They were crude, no-maintenance lights that put out a tremendous wallop. They could bum upside down, they lasted a really long time, and I could hang and burn them quickly. I also used a bunch of Socapex lights, which are six rock-and-roll aluminum Par cans on a bar with one multi-pin connector cable; two clamps held it on the truss, so it was really fast. Then I had big 30-light Raybeams, which are like nine-lights with 30 bulbs. It's a killer of a light because it's got 30,000 watts and sends the light flying. I used that for the day scenes in Gotham Plaza and elsewhere to make the contrast in the picture. I wound up using almost no HMI lights. I went with the traditional tungsten bulb lights and bunches and bunches of 1OKs, but the lights that really shaped the scenes for me were the Par lights up on the trusses."

Using Panavision equipment with Primo lenses and the slow film, Czapsky tried to create a sense of contrast from settings he laughingly described as "black on black. Everything I had in front of me was black, and I had to separate this black thing from that black thing. Sometimes I'd stick the spot bulbs up in the maxis and use them as a backlight so I could get the foot candles from them to overexpose for the slow film."

The Penguin's scenes, the first to be shot, turned out to be Czapsky's favorites. "It was the most fun for me because of the character," he smiles. "The Penguin had such a noble story behind him, and he was a new character, a new costume, a new personality. It was also the first test of all the things we planned, and my memory of it has a lot to do with getting things going."

Czapsky allowed himself to be influenced by the square, refrigerator-look of the character in devising his approach to the Penguin's scenes. "We were so overwhelmed by Danny's performance that we didn't have to think about what to do visually," he says. "When I watched him in rehearsal, it became very clear what the approach should be.

"The only problem had to do with the paleness of the Penguin's makeup, although the whiteness of the character was less difficult than dealing with the blackness of the sets," he adds. "It was just another part of the contrast control. Since I was shooting the 48 film, the makeup had a tendency to come out warm — orange. But after I did two makeup tests, I realized I had to keep the light right at 3200 or else blue it up some, and that helped the makeup photograph white."

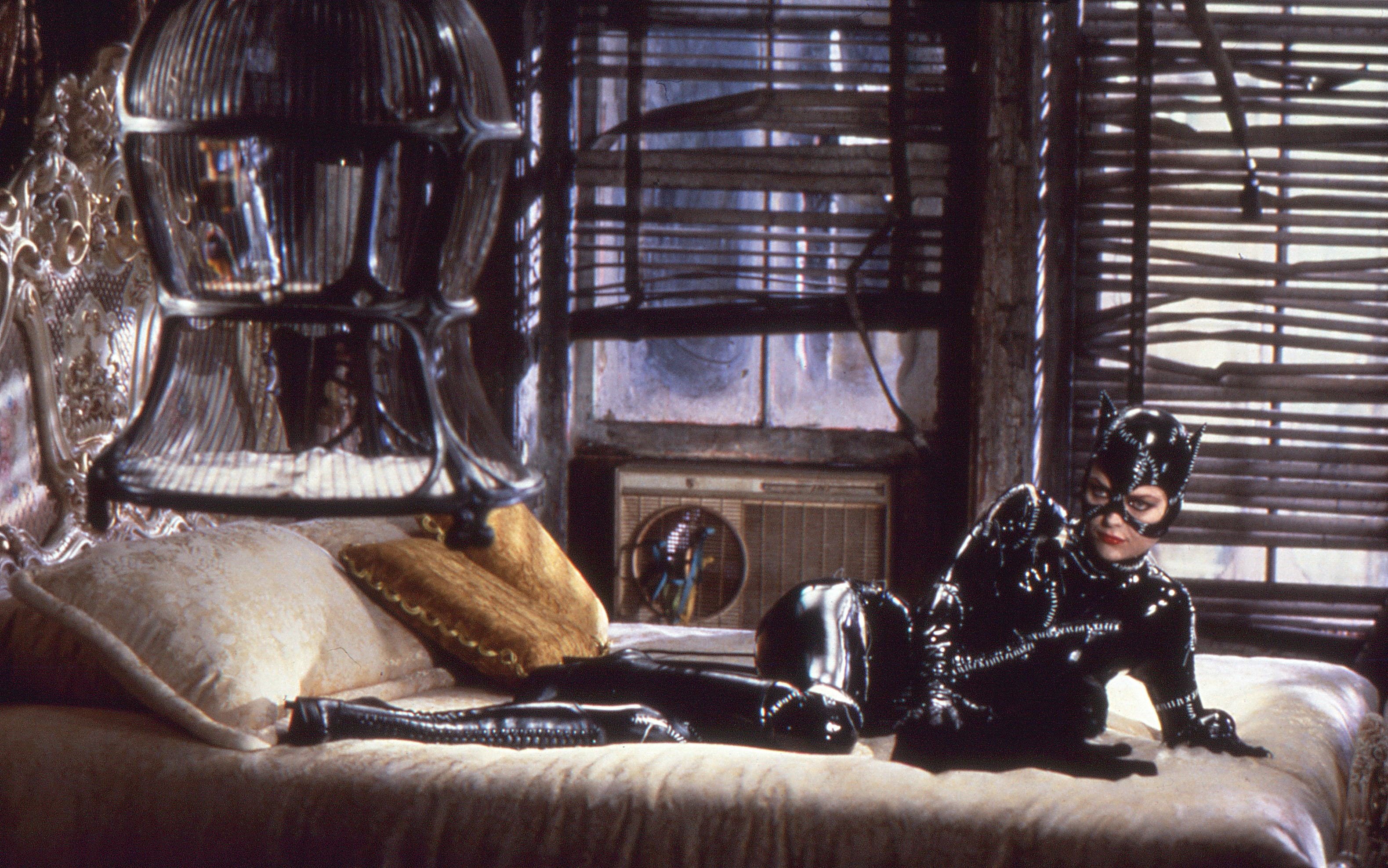

And what of the Penguin's sleek, seductive, leather-clad cohort in crime, the nefarious Catwoman? "I lit her like a car!" Czapsky laughs, assessing the problems in lighting the glossy costume of the villainess. "We had to watch for things we could see in her suit — lights and the camera — which is literally the same thing I run into when lighting a car. I was able to use that to my advantage; I'd just bash her with light from behind and really didn't worry about over¬ exposing it."

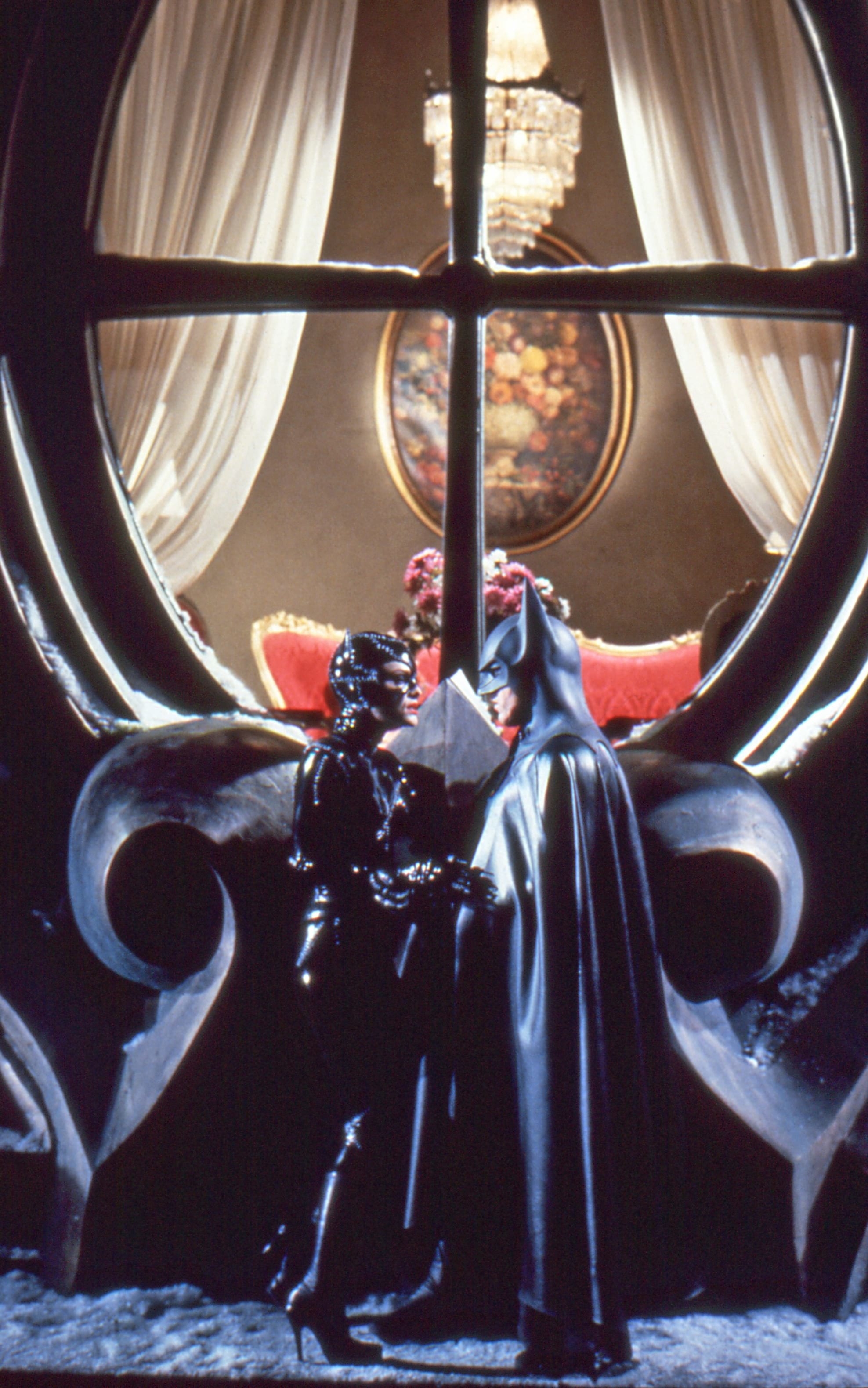

While Czapsky shot Catwoman as a perpetual motion machine who was always moving, slinking and slithering, he says that Batman himself was usually captured in a posture or pose, appearing almost as a sculpture. So when Batman began to reveal his dark side to Catwoman, Czapsky decided to keep the caped crusader a mystery. "I wasn't sure how much to hide him — how much to make him a shadow" he says. "I avoided letting light fall on his face. Sometimes I let you see who he is, depending on which part of the story we were at. I didn't want to overdramatize the lighting. I get tired of doing the same thing every timei, but there were certain things that worked, like putting a little kick light on the side of his face. The hard part was to not become too formulaic about it. I thought he looked best when he first met the Penguin."

As that fateful meeting occurs, Catwoman decides to make her own impression on the caped crusader by reducing Shreck's Department Store (a wry homage to German actor Max Shreck, who played the lead in the silent vampire classic Nosferatu) to bombed out rubble. When it came time to start blowing things up, Czapsky found working with the slow film a plus. "It was really good at holding the information," he opines. "Since I was shooting at 2.8 or 4, I was using a lot of light anyhow. We set up a few cameras and we evacuated most of our crew. We used doubles in the shot and we had the fire department there. There was a tremendous explosion, a full-on fireball in this giant set. The flame shot way, way out there; I think it singed the back of the woman who doubled for Michelle Pfeiffer.

When we did our closeups afterwards, we put lights on the actors and shot a higher stop so the fire didn't go white. It was a big triumph because it turned out so well."

Czapsky felt equally proud of his work in the Penguin's lair, a secret hideaway located in the Arctic World exhibit of a derelict zoo in Gotham City. The story reveals that the infant Penguin was abandoned at the site by his parents and raised by his featherless friends. The frigid retreat was built in all of its Gothic splendor on Stage 12 at Universal Studios; it was the only set to be shot off the Warner Bros. lot. In addition to being one of the few sets with an actual ceding — a vast web of interconnecting arches — the Penguin's lair also boasted a full-scale island surrounded by water, which provided the key for Czapsky's lighting approach to the operatic setting: "I lit that set using lights reflecting off the water. It was the one set where I used HMIs. I needed something that powerful since I was dealing with reflected light and they're blue by birth. It took awhile to figure out, but by the end of the shoot I was bouncing Xenons off the water and putting mirrors in to supplement the reflections. It was tremendously complicated — we had real penguins, puppet penguins, little people in mechanical penguin outfits, the Penguin and his gang, fire and water—but the crew was into it, even when we had to work in freezing water, because we were shooting with real penguins. It was a lot of fun."

The subterranean entrance to the Penguin's lair was something Czapsky describes as "a toxic waste dump sewer. It fell on me to make it look like that," he sighs. "Tim suggested we do it with color. I used green and sulphur colors, the only gels I used on the film, and I remember being startled by it. All of a sudden I'm going for a weird green or orange look. I got a little frightened about overdoing it at first, but then I thought it was so interesting looking it'd be hard to screw up."

Czapsky says he prefers the scenes in the Penguin's lair because the set was one of the most impressive and complete. "For me that was the best set. I'd never been anywhere that was all set before," he says. "The other sets were too small; the ideas were bigger than the space. As soon as you decide to film inside rather than outside, the stages just don't seem that big. We were always fighting that. There was no room, we had to put our lights in fairly quickly and there wasn't a lot of preplanning; we just did it on the spot."

Perhaps the best example of the overbuilt sets is Gotham Plaza itself, which will appear in the film largely as matte paintings and miniatures. Czapsky primarily used his pre-installed hanging trusses with Ray lights, maxilights and rock-and-roll cans to illuminate the vast set, depending on ground-based portable units to light the actors in the scene. But the greatest challenge on the Gotham Plaza stage was not lighting it, but finding ways to keep the camera prowling over the irregular terrain. "I used the camera remote as much as possible on the Matthews MC88 camera arm" Czapsky recalls, "but we always had to be prepared to level something out and go on the dolly. We had a bunch of platforms and a good crew that was able to put the floor in quickly. We were breaking records putting it in—we were moving! "

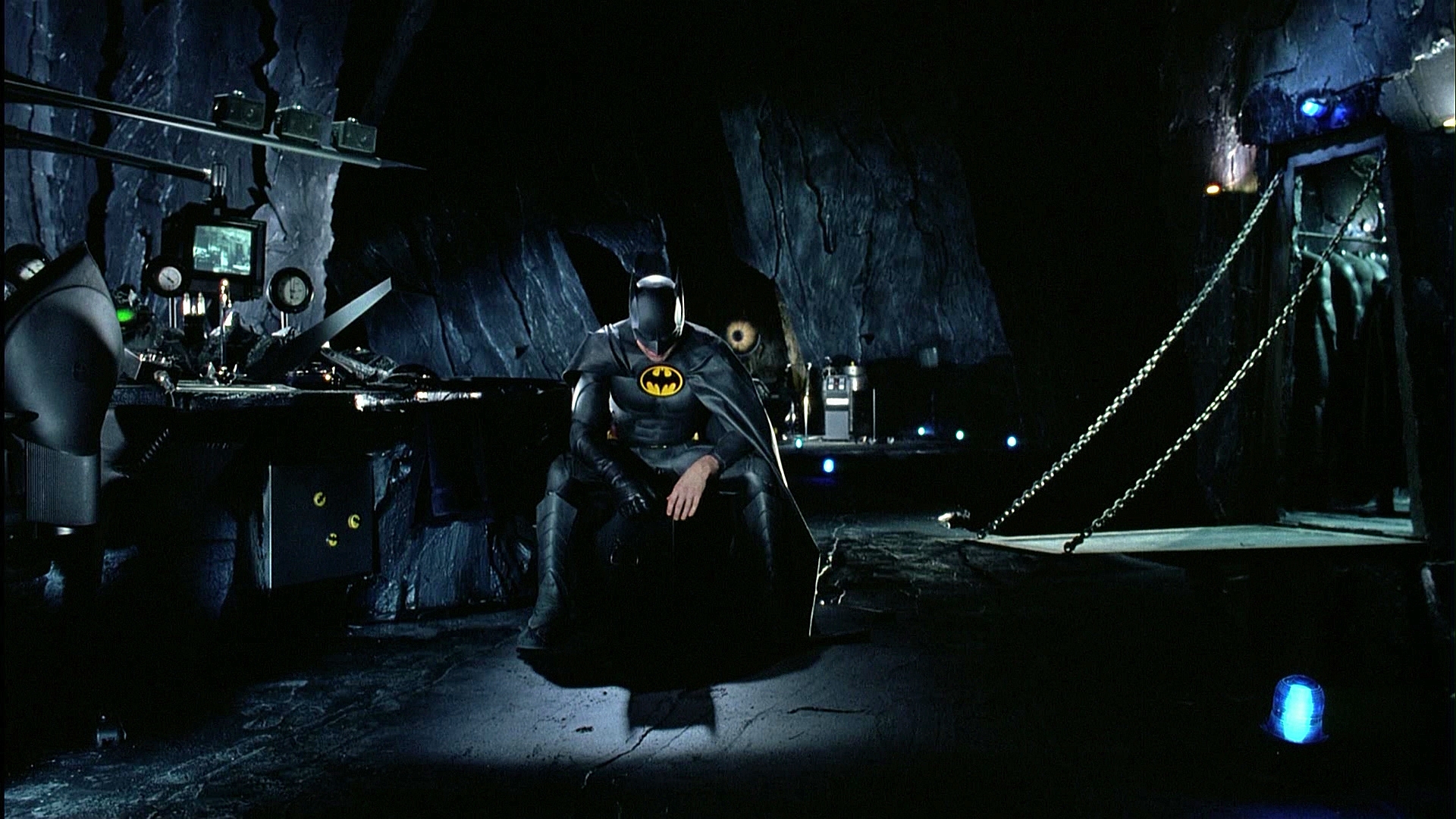

On the opposite extreme, the Batcave set, shot near the end of the schedule when money was running out, was almost non-existent. "It was a void," Czapsky grins. "We were in a little stage on the Warner Bros, lot which only went 35 feet high, so it was like a little TV studio. They decided to make the major portion of the Batcave a matte painting, but this wasn't one of the things that was jobbed out; it was done by us because we actually had Michael Keaton and Michael Gough in the shot, and that made it ours. We had just a few set pieces to work with and it looked a little like a coal mine. That shoot was more like a big moving job; there was a piece of coal over here, a piece of coal over there, and we had to shift those few pieces of scenery around. We didn't have a week of setup; we just did it on the spot. The matte guys came in with a special Vistavision camera to shoot latent image plates, so we had to rig the camera and put the glass in front to black out certain areas. I used a lot of arc lights when I shot inside to add some nice shadows and a blue look. We shot a bunch of stuff with Batman and Alfred by a console, and some goofy stuff with the Bat-closet and the Bat-chute, and I liked the way the color came out from the combination of those lights with the 100 ASA film. We were using either an 18 or 20mm wide-angle lens to make the plate appear more expansive, which created its own complications due to having such a wide lens in such a small space."

The well-appointed study of Batman's alter-ego, Bruce Wayne, was also shot towards the end of the schedule, but was quite a bit more impressive than the physical Batcave set. "That set definitely had to do with overstatement. Bruce has a gigantic fireplace; this guy is wealthy!" Czapsky laughs. These shots were designed to show the millionaire crimefighter being summoned by the Bat Beacon, which comes pouring through a huge round window at one end of the darkened study in palatial Wayne Manor. "Bruce is sitting in a chair, deep in thought, and all of a sudden he gets hit by the Bat Beacon coming through the window. The Bat Symbol itself was projected onto the wall using a high powered HMI source slide projector, and it was supposed to look like it was the source for the entire scene. We decided to put the beam in later over the projected image of the Bat Symbol as an optical effect so it would match the special effects shots before it. Since we were working with the slow film, I had to measure all the time with my spotmeter to make sure the Bat Symbol didn't blow out. I lit the window area from outside as though the light was coming from the Bat Beacon, and I also used a few lights on the side. It's very, very weird. There's almost a fascistic element to the imagery."

Czapsky admits that it's strange to be wrapping his first film in the spotlight after all the years of working in the low-budget realm; now that the eye of the camera is on the photographer himself, he doesn't know how to react. "I still don't believe it," he smiles. "When you get to be close to what other people feel is a sure thing, it's a little unreal. I appreciate it when someone like Tim Burton sets it up and encourages me to do good work and to be creative and gives me a lot of responsibility; I just shine. There's nothing I can do but outperform myself and do a good job. Working on a film set and the satisfaction I derive from that really doesn't have much to do with the movie playing to big houses in theaters. I hope for that, but mostly I've been disappointed. That's only reserved for a few movies anyhow; they can't all be megahits. Whether people see it or not isn't under your control, but I hope my work and everybody else's work came out well. I guess I'll believe it when Batman Returns actually turns out to be a hit. I have a good feeling about it."

Czapsky would later be invited to join the ASC, and photograph such features as Matilda, Ed Wood (also directed by Burton) and Blades of Glory, as well as the series Shades of Blue and Quantico.

For more on the Caped Crusader, check out our retrospective on Batman: The Movie (1966).