Greyhound: Battle at Sea

Cinematographer Shelly Johnson, ASC and director Aaron Schneider, ASC join forces on this World War II drama.

Unit photography by Niko Tavernise, Courtesy of Sony Pictures

The director-cinematographer collaboration is perhaps the closest and most time-intensive partnership on a production, and it gained new dimension on the World War II drama Greyhound because cinematographer Shelly Johnson and director Aaron Schneider are both ASC members. Because of Schneider’s experience behind the camera, says Johnson, “the collaboration was different across the board, and only in a positive way.”

“There’s a common language and a common pace, but there are also a hundred different things that go unspoken but are understood at the same time,” Schneider says of the experience. “Certainly, a director who’s shot before has a greater sense of empathy for what a cinematographer has to go through on a minute-by-minute basis. And, as a cinematographer who’s been forced by directors to make compromises, you’re also, as a director, aware of the compromises you might have to ask your cinematographer to make. And because you both know that world, there’s a different level of appreciation and respect for what the other person’s dealing with in the moment.”

Schneider and Johnson had known each other through the ASC for many years but had never worked together. Schneider’s previous directing credits, the Academy Award-winning short Two Soldiers (AC Feb. ’04) and the indie feature Get Low (AC Aug. ’10), were both shot by David Boyd, ASC, who has since launched his own directing career. In search of a new creative partner for Greyhound, Schneider reached out to Johnson “not because of any single film he’d shot,” he says, “but out of admiration for his career.

“When I was a DP,” Schneider continues, “I followed the story of Shelly Johnson rocketing to stardom. He suddenly popped with Jurassic Park III [in 2001], and when you’re coming up as a DP and one of your peers does that, it sticks with you. I’ve got this buddy from my USC film-school days, and over the years, we’ve continued to talk about our favorite DPs, and somewhere along the line, Shelly’s work crept into our conversation and just kind of stayed there. Shelly and I had known each other a little from conversations at the ASC, and when I started looking for someone to shoot Greyhound, he immediately came to mind.”

Johnson, whose credits also include The Wolfman (AC Feb. ’10), Captain America: The First Avenger (AC Aug. ’11) and Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters, recalls, “I’d had just a few conversations with Aaron, but I highly respected him as a DP, and I always valued my conversations with him. So when he called about Greyhound, I was really tickled.”

Set in 1942, Greyhound follows U.S. Navy Cmdr. Ernest Krause (Tom Hanks) over 72 hours as he tries to protect a convoy of U.S. ships from German forces in the Battle of the Atlantic. Hanks, whose interest in American history is well documented, also wrote the screenplay, which is based on C.S. Forester’s novel The Good Shepherd.

The independent production was shot in Baton Rouge, La., over 35 days in the spring of 2018, and its post-production schedule was extended to facilitate visual-effects work with Double Negative that was supervised by Nathan McGuinness. Johnson was midway through the picture’s final grade with colorist Bryan Smaller at Company 3 when Covid-19 prompted California’s statewide shutdown of non-essential businesses in March. The cinematographer spoke to AC while waiting for that work to resume, as did Schneider, who was also affected by the stay-at-home order.

Greyhound is now streaming on Apple TV Plus.

In adapting Forester’s novel for the screen, Hanks hewed closely to the author’s emphasis on Krause’s point of view, both physically and emotionally. “Most of the film is about the intimacies and intricacies of Krause’s command dilemmas,” says Schneider, “and I was very interested in exploring the story from an almost hyper-subjective point of view not just visually, but also psychologically and emotionally. The concept was to drop an audience into the pilothouse of a World War II destroyer, point the camera at the captain across the room who’s in charge of 37 ships in the middle of U-boat-infested waters, and allow the audience to engage in it visually and experientially. The film isn’t classical or expository; it encourages the audience to lean into the film and learn about this man and his environment as the experience evolves.”

Schneider understood what this would mean for the director of photography: achieving visual veracity in a seagoing thriller that would be shot almost entirely onstage; aligning the audience with a taciturn protagonist who communicates mainly in technical language; and finding ways to, he says, “reveal the drama underlying something very procedural.

“My jumping-off point for this movie, and something I shared with Shelly early on, was the scene in the air-traffic-control room at the beginning of Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” Schneider continues. “You’re in a world you’ve never been in before and the air-traffic controllers are using language you’ve never heard before, but you still intuitively understand the drama unfolding underneath it all: a UFO sighting. There’s no cut to the UFO, no cut to the pilot seeing the UFO, just a blip on a radar screen and the emotional engagement of the pilots and the controller trying to stave off a disaster. It’s the procedural language and the audience’s unfamiliarity with it that give the scene its veracity. That procedural environment is what makes it all seem so scary and hyper-suspenseful.”

“That scene was a very good example of how we could make our movie speak,” says Johnson. “Aaron said to me, ‘Our whole movie is basically that: it’s about the drama taking place between the dialogue.’ So much of Tom’s performance happens between his lines — Krause will say something, but it’s what he’s thinking before and after he speaks that’s actually where the scene is. We had to get into his head, put viewers right next to him on deck and give them the same situational awareness.” That meant learning Krause’s language. “When Aaron interviewed me, he said, ‘Here’s what I want my DP to do: I want you to learn about sonar tracking. How does sonar work? How do they establish the threat level of a potential target and plot an engagement? You need to understand their language because you’re going to be educating the audience.’ And, of course, while the audience was learning, they’d still need to connect with the drama. I thought that was a wonderful challenge.”

“There was method in that madness,” says Schneider. “Think of that awesome shot in the climactic chess match in Searching for Bobby Fischer when Connie [Hall, ASC] racks focus from one chess piece to another to reveal our hero’s winning move before it even happens. If you don’t understand how chess works, if you don’t understand the inherent drama and the visual properties of the game, you can’t dramatize a moment like that. The more you understand what you’re shooting, the deeper dive you can take into it visually.”

Ultimately, much of Johnson’s sonar education was provided by a coterie of enthusiasts he met in Baton Rouge while scouting the USS Kidd Veterans Museum, a Fletcher-class destroyer docked on the Mississippi River that the filmmakers planned to use for some exteriors of Krause’s ship. “Everyone on the museum staff loves to talk about the ship, and they taught me a lot about its inner workings,” says Johnson.

The majority of Greyhound is set in the destroyer’s pilothouse, where Krause maintains a constant watch as his crewmembers rotate in and out in shifts. Production designer David Crank built two sets — the pilothouse interior (including a portion of the deck surrounding it) and the ship’s combat information center (CIC) — onstage at Celtic Studios in Baton Rouge. “Krause hardly ever leaves the bridge,” Johnson says, “but there’s so much communication between him and the CIC that we once shot those two sets simultaneously, with [A-camera/Steadicam operator] Don Devine up on the bridge and [B-camera operator] George Billinger in the CIC.”

During most of Johnson’s eight weeks of prep in Baton Rouge, Schneider was at work in Los Angeles, attending to casting and creating animated aerial views of the story’s tactical engagements that could serve as a previs to help guide the actors on set. “Every scene involves action in the pilothouse as well as action outside the portal windows, and everything Tom’s engaging with outside is a visual effect,” says Schneider. “Because this was a relatively low-budget production, we didn’t have the resources to previsualize the entire movie, but the overhead animations were crucial in communicating a sense of ‘tactical awareness’ that the actors could draw upon. Everything you see Tom do was built from his actor’s imagination as he was staring at a series of LED lights and reacting to these virtual battles, so at wrap, we only had half a movie — everything else would come later. The overhead maps made sure Tom’s performance married up with the physical world that didn’t exist yet.”

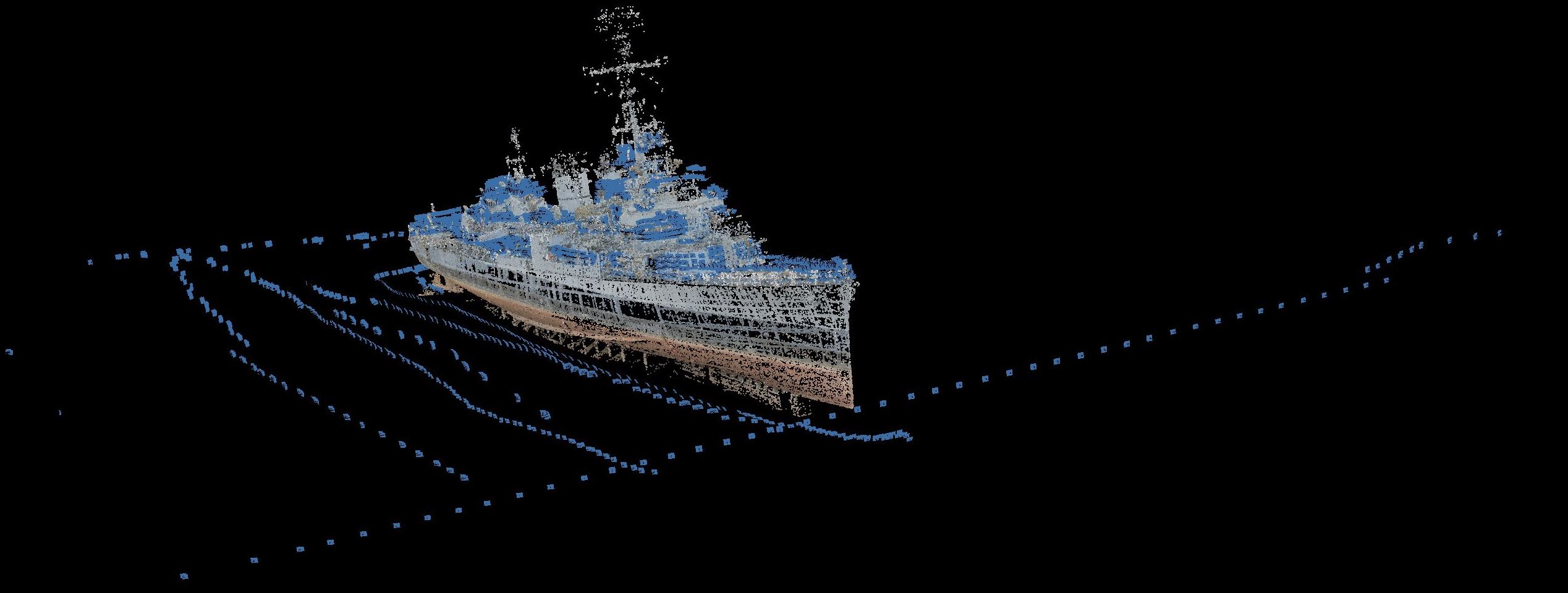

The pilothouse set was built on a gimbal whose movements were programmed to match some key previs experiments that Schneider, a self-taught VFX artist, made using Autodesk Maya. Prior to production, he and 2nd-unit director Steven Quale used photogrammetry to create a high-resolution model of the USS Kidd from more than 10,000 photographs they had taken of the ship. By employing Nvidia’s WaveWorks, a game-engine simulation that was ported into Maya, Schneider was able to simulate actual ship-to-ship photography in a digital environment. “WaveWorks lets you input the wave size, the ships’ speeds and their mass and then generates physics-based ocean and ship movement,” Schneider explains. “The goal was to create the inherent energy and chaos of actual open-ocean photography — to ground our VFX in that reality so that the live-action and digital photography were speaking the same visual language.”

“Aaron’s experimentation enabled us to figure out, for example, that if there’s a 5-foot sea, the camera alongside might heave up 30 or 40 feet in relation to the moving ship, so we could program the gimbal accordingly for that moment,” says Johnson. “We used the same calculations to do some wider exterior shots on the USS Kidd with a 75-foot SuperTechno; the grips had to do 30- or 40-foot rises on six-second cycles, which was mind-blowing to see. And in the CIC set, which was not on a gimbal, George could mimic that same cycle because he’d been on the gimbal and knew the rhythm by heart.

“Don and George really figured out how to make the movement expressive,” Johnson adds. “When they were shooting simultaneously, we’d have shots in the pilothouse and in the CIC on side-by-side monitors, and they matched perfectly. Those guys are really the MVPs of this movie.”

Only slivers of the outside world are visible within the pilothouse, which Johnson describes as “basically a small armored box with nine small portholes and two hatches. If you want to look outside, you have to walk right up to the porthole, so, naturally, Krause consistently takes that vantage point.” For the interior lighting, Johnson used warm LiteGear LitePads tucked in among the instruments overhead to augment dozens of small, shaded practicals with orange globes. “In most cases, we had cooler light coming in from the hatches and portholes and warmer light coming from overhead, and we established a chromatic separation between the two,” he says. “That color contrast was a useful component in communicating the evolving time of day. The sun doesn’t come out till the end of the film, so everything’s in indirect light.”

The exterior-lighting plan, executed with gaffer Bob Bates and GrandMA2 console operator Dana Hunt, had to not only convey the conditions outside, which at any given time might include stormy weather, muzzle flashes, explosions and flames, but also orient the audience to the ship’s position and movements and set the tone for the visual effects that would be added later. The mandate, says Schneider, was “to throw out the glossy Hollywood trick bag and put the most truthful light possible into a visual-effects-heavy film that lives or dies on photorealism.”

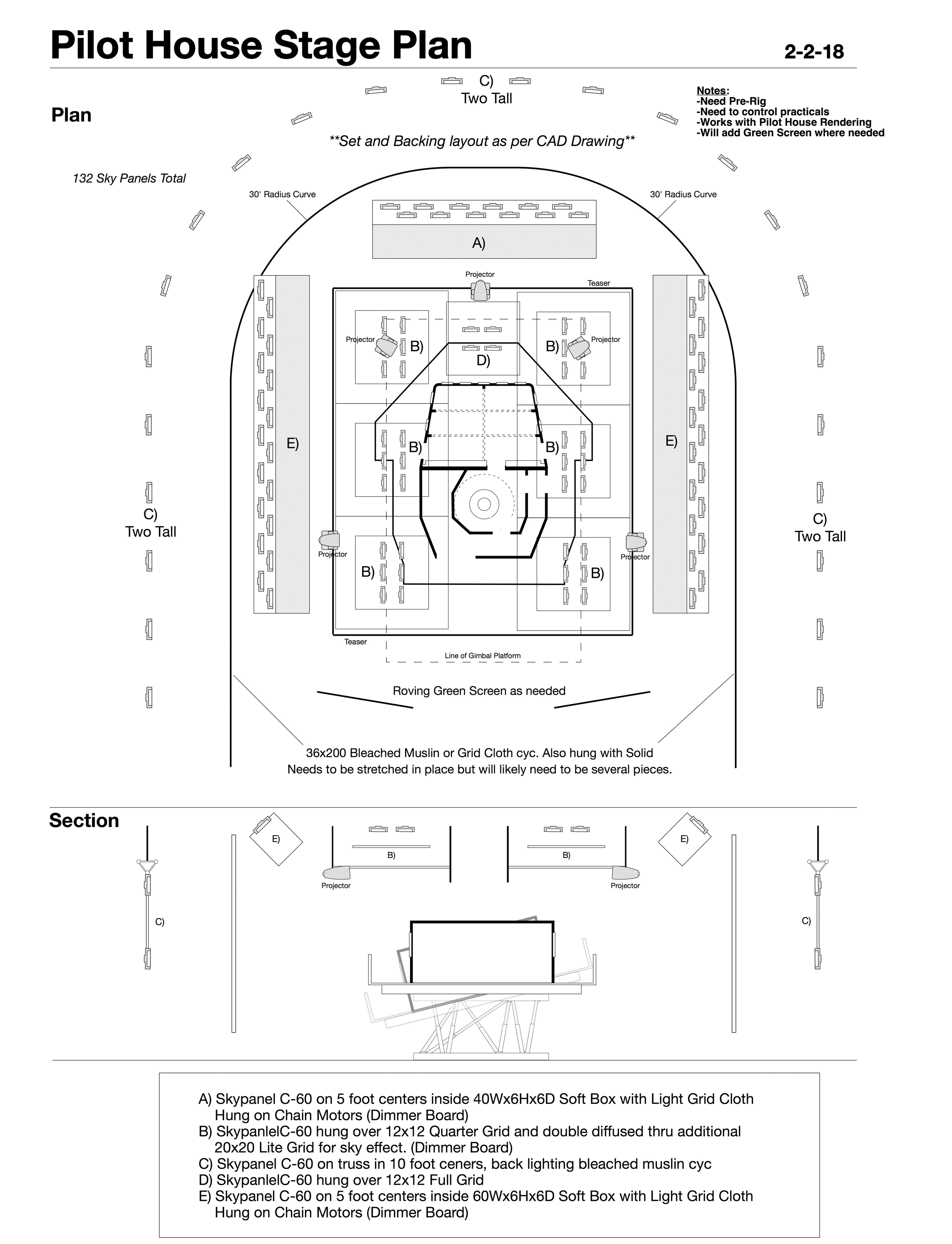

With that in mind, Johnson surrounded the pilothouse with white screen — a mix of bleached muslin and Grid Cloth — instead of greenscreen. “Because our ship is traveling through weather and sea spray, I knew greenscreen would just reflect green into the set and render all the light unusable,” he says. “Plus, we were doing some pretty massive movements on the gimbal, which meant the greenscreens would have to be rather large to cover that movement, so any lights would’ve been placed around them and sent light into the set at an unnatural angle. White screens allowed the light to come in from the backgrounds and reflect in at the proper angle, giving the whole set a much more natural feel.”

Additional frames of Grid Cloth topped the white cyc to facilitate skylight. Bates’ crew backlit and toplit the rig with 132 Arri Skypanel C-60s (see diagram), and Johnson worked with Hunt to program lighting cues to follow the beats in the script.

“Tom’s script follows a series of four-hour watches, beginning in early morning and progressing through the next three days,” Johnson says. “In prep, I broke down how each watch would be affected by light and wrote a manifesto, going scene by scene and describing the sea-state [that is, wave height and shape], the visibility of the horizon, the amount of atmosphere, the color of the water, the color of the sky, and the effect of ambient light outside vs. the practical light inside. Once that document was approved up the chain, we programmed the SkyPanels to emulate that. We had the whole movie more or less stored on the dimmer board before we started, which allowed us to shoot in sequence.

“Getting all that technical preprogramming out of the way ahead of time frees my brain so I can better see the options presenting themselves on the set,” Johnson continues. “A big part of our work on Greyhound was making every shot speak as loudly as possible, which meant that if we were making adjustments between takes, it was because we were working to bring clarity to each screen moment. By doing all that technical work ahead of time, I could just touch up the lighting accordingly as we shot.”

Don Devine and George Billinger, both members of the Society of Camera Operators, worked handheld on all but a few shots. This was partly a concession to the very tight quarters — Johnson estimates the pilothouse interior was 10'x18' and had 14-16 characters in it at a time — but it was also in keeping with what Schneider describes as a “visceral, almost documentarian approach, a little chaotic, not too polished.” Johnson, adds, “It was about making the shot feel proper, going for truth on a gut level.”

The filmmakers discovered that Panavision’s Millennium DXL and Sphero 65 lenses made the most of the color contrast between the interior and exterior light, although Johnson had actually selected the package for other reasons. “When Aaron pitched shooting large-format,” he says, “he expressed a desire for the camera and lenses to contribute toward immersing the audience in the world of the pilothouse. We both agreed that using the longer spherical focal-lengths associated with large-format shooting, while still allowing us a wide perspective that would compose our characters in this world, would be a meaningful choice.” Schneider adds, “It’s not only more flattering to the actor, it’s also more immersive because you don’t feel everything in the background has been diminished by the wider focal length. That was perfect for this movie because we were going to follow Tom through this little fish tank of a pilothouse; we were going to be backed into corners, and we didn’t want to have to throw on a 12mm lens and distort everything.”

“The Millennium DXL2 was just out at the time,” Johnson recalls, “but we were a ‘little big movie’ with a limited budget. I tested the DXL and thought it was just right for us, and we recorded in the 8K VistaVision format [at 5:1 compression]. I wanted the Sphero 65s based on what I’d seen and read about them, but they were in such demand I wasn’t able to test them, and I wasn’t even sure we’d get them in time for our shoot. They actually arrived two or three days before we started shooting!

“The [8K Red Dragon] sensor in the DXL in particular separates warm from cool, but the degree to which it would do that wasn’t foreseeable until we got the lenses,” he continues. “With the very first setup, I saw how the DXL separated color tones in a chroma-sensitive manner, and then was inspired by the way these vintage optics melded the colors back together with analog elegance. It was a fantastic marriage of old and new.”

The Germans mount their first major attack on the American convoy at night, and establishing a night look was one of Johnson’s first orders of business in developing his manifesto. “To me, the most difficult lighting setups are ‘night exterior-desert’ and ‘night exterior-ocean’ because those are lightless settings, and when you light them artificially, there’s going to be a point in those vast frames where your lights run out,” he says. “It’s basically pitch-black on the open ocean at night, but plunging our story into total blackness wasn’t going to work for us. The script called for enough visibility that we can see movement on the horizon, U-boats and star shells in the sky.

“As soon as the exterior gets darker than the interior, the lighting in the pilothouse goes red to help the eye adjust. So our night was a dark dusk-for-night look, a situation where the red light inside allows your eyes to open up so when you walk out on deck, you can see because there’s moonlight illuminating the clouds. Also, the ship is traveling through weather, and all that spray and vapor help lift the shadows and provide visibility. You can say pitchblack would be more realistic, but I believe what’s right for the story is what’s fitting. That’s what matters.”

— Shelly Johnson, ASC

“When the U-boats attack, a star shell goes up, enabling the Americans to see the enemy, and then Krause starts calling for rudder commands. His ship turns left and right to navigate through the convoy to the ship that’s on fire, and then he circles it. We’re on a stationary set, so our lighting had to suggest all that action, and it had to be programmed in such a way that the audience always understands where Krause’s ship is in relation to the situation. We programmed layers of interactive lighting. We had a cluster of SkyPanels on a scissor lift for our moving star-shell effect; we lit up a fire effect on 12 SkyPanels and chased it across the muslin; and we used other SkyPanels for all the muzzle flashes from the Americans’ big guns. We even had some small LEDs mimicking tracer fire. And Dana had to bring all these elements in on cue.

“It could have been so complicated,” Johnson adds, “but our grip and electric crews made it look so easy.”

During the shoot, the filmmakers applied a custom LUT that Johnson developed and refined with dailies colorist John Vladic of Technicolor. “We were on a rather specialized color workflow because the VFX team requested that we grade using ASC-CDL values they could carry into their workflow,” says Johnson. “Technicolor built a bay for us at Celtic Studios that included a [Blackmagic Design] DaVinci Resolve and a 4K monitor, and every night at wrap, I’d go in there and work with John on the color for everything we’d shot the first half of the day; it was very much like a film workflow. We could view footage in a controlled environment, and John helped us create a LUT that set us up nicely for the VFX.”

Early on in the shoot, Johnson noticed he and Schneider were standing on opposite sides of the room when they watched the actors rehearse. “Normally when you see a director and DP do that, you think, ‘These guys are disconnected,’” Johnson says with a laugh. “But invariably, after rehearsal, Aaron would come to me and say, ‘What’d you see over here?’ And I’d ask, ‘What’d you see over there?’ I think 90 percent of the time, we went with Aaron’s take on it. I really liked how he was able to articulate the inner drama of the scene and convey meaning in moments that would ostensibly be found in the white part of the script page. The procedural dialogue was the structure on which the real story was built, and Aaron was masterful at translating those unwritten attributes into visual cues.”

Schneider notes that the virtual nature of the project had its challenges. “Because everything Tom was playing against out in the water was a mark on the wall or an LED light,” the director says, “during rehearsals, I was not only looking at the actors to determine the most dynamic way to cover it, but also trying to visualize the action or bits of narrative information outside the window that would be created later. The battles going on outside were like an invisible character in the scene, and because we couldn’t previs the entire movie, there were times when I was the only one who knew what the other half of the scene would be. That’s sometimes a tough spot to be in as a director, and you need a good partner-in-crime at your side. Shelly is a blazingly fast cinematographer and very fun to work with, which are important qualities, but he’s also loyal, which goes a long way, too. This movie was challenging, and we had to stick together to make sure we didn’t get distracted by all the complexities.

“Filmmaking is a creative endeavor,” the director adds, “but a movie set is also a blue-collar workplace where you manufacture the movie shot by shot, and not everybody needs to engage in all the levels of thought going into it in order to do their jobs well. This movie was a bit lonely at times because of that complexity, but when I was in that brain space and needed somebody to deep dive with, Shelly would go there with me. It was great to have him as a partner on this.” Johnson’s manifesto proved useful throughout post, especially when he began working with Double Negative’s McGuinness. “Nathan did a brilliant job with the bigger views that help establish the geography and set up the U-boat threat,” says Johnson. “I was happy to work with him because I’d shot our foregrounds to extend to a very specific type of background lighting that wasn’t immediately apparent to him, and he was delivering shots as EXR files that had grading baked into them. He welcomed my input, and it was a fantastic collaboration.” That spirit defined the entire project, he adds. “In some ways, shooting a movie is almost like a competitive sport — you really have to find that focus going in and psych yourself up for what’s ahead. And over the course of it, there’s fatigue, there’s everything a DP has to deal with. But on Greyhound, I was consistently inspired by the great people around me. I’m a better cinematographer having worked with Aaron. Every day on my way up the stairs to the gimbal, I’d think, ‘Every DP in the business wants this job, and I’m very lucky to have it.’ And that helped motivate me. No matter what happened that day, I was ready because I was just so happy to be there.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

2.39:1

Digital Capture

Panavision Millennium DXL

Panavision Sphero 65

You’ll learn much more about Schneider and Johnson’s collaboration in the film from this Clubhouse Conversations interview conducted by Eric Steelberg, ASC: